LEAVING

Twilight, the house dark,

a Barred Owl, in a great folding of wings,

slipped onto the walnut branch reaching

a shadow across the picture window—

a forest space without leaves or shadows—

faced me, each watching the other

in his natural habitat. Didn’t stay,

disturbed perhaps by my laptop’s flickering

or my face large in its light.

Did I seem threatening behind the glass—

a creature that could move but make no sound?

I hit send on my e-mail

and in that looking away it was gone.

On the front deck this morning

I stole a few moments before

leaving for the airport; joining

my kind in another week

on the road. In the space

between chair and trees,

my wing tips touched the deck

and were gone.

BUCK

He’s around again. Bigger than ever this year. Saw him yesterday sparring with a younger male. Tolerating him, really. Heard the click-click of antlers from the stand of pines up the slope above the house. The smaller male lined his antlers up with the big guy’s, then tried shoving, forehead to forehead. May as well have been pushing one of the pines. Buck seems to have a sense of humor this year.

Usually he just cruises through pursuing a doe, forcing her back into the forest preserve. Last fall was different. He had a gash on his left flank, the hair dark and matted from licking. I can’t imagine how anything got around that rack. He spent most of a day in the sun across from our front door, up-slope above us. The does bedded down around him and the fawns hung around — learning the subtexts. When I went out on the deck to throw them a few ears of corn the does didn’t squabble and kick at each other like they do the rest of the year. He ignored it but sniffed the air when I was outside. Conventional wisdom is to stay away from the bucks during mating season; I stayed within reach of the door. In early evening he followed them over the hill into the forest, nostrils flaring as he smelled the grass where the does had laid.

Sometimes worlds collide. During mating season, when I need to go out I use the garage. At first light on Fridays I drag the wheeled trash bin out to the street. The crushed rock drive curves through the trees and down the slope to the pavement where the truck comes in the morning. The garage door opener works quietly but the bin sounds like an irritated kettle drum when I drag it across all that stone. Climbing back to the house I like to amuse myself by trying to walk without making a sound. And today, as I came around a stand of oaks, there he was above me, staring into the garage. He turned his head; looked directly at me. Repositioned his feet.

It’s a strange sensation, being measured by a large, heavy animal. He squared up to me, his nostrils flaring, sides heaving as he tested the air. Then, catching the scent of something—perhaps what he had been following—he gave a loud warning snort, laid his antlers back and trotted across the drive and down into the watershed, moving like a Tennessee Walker. Cadillac smooth.

NIGHTFALL

Bangkok

Rainy Season, 1972

Rain pearls soft on the drumhead of the pond.

Wind sweeps them in with silken brush.

Frogs at our feet push twilight into dark,

and lily, raising light from water, leans back,

open-mouthed to admire the night.

In Buddha’s greatest lesson, it is said,

he simply held up a flower.

John Hicks answers

THE WILD CULTURE SCRIBBLER'S QUESTIONNAIRE

What is your first memory and what does it tell you about your life at that time and your life at this time?

When I was three or four years old I wandered away to the neighbors. Mr. Armstrong was on his carport doing some sort of work on one of the wheels of his car. I had watched my dad change a tire and wanted to tell him about it. I think Mrs. Armstrong must have phoned my mother because I can recall her voice through the open kitchen window: “Yes, he’s here. Do you want me to send him back?” I think Mr. Armstrong must have been doing something else to his car; he didn’t want to hear instruction on how to change a tire. That didn’t stop me from wanting to express myself. In later years I just moved into print.

Can you name a handful of artists in your field, or other fields, who have influenced you — who come to mind immediately?

For a long time I tried to understand my mother’s paintings. That gave me an appreciation for design. Jude Nutter’s poems gave me an appreciation for how fascinatingly complex poetry can be. Ted Kooser gave me respect for the significance of the everyday; and, of course, Garrison Keillor’s story-telling.

Where did you grow up, and did that place and your experience of it help form your sense about place and the environment in general?

Grew up in northern San Diego County when it was sparsely populated. I loved to get out of the house; to explore the dry ridges and arroyos that ran parallel to the coast and down to the sloughs that drained into the Pacific. Being an arid climate the wildlife was harder to spot, but with patience and being alert for changes, I found it: a warren of trapdoor spiders, a spot where quail take dust baths, and the like. And it was a time when parents could let their kids walk the several blocks to the beach without worry. I had sand creatures, kelp, jellyfish, and later girls. Always something to see. I don’t go back. The places I used to enjoy are under houses and malls and streets, and a crushing population.

If you were going away on a very long journey and you could only take four books — one poetry, one fiction, one non-fiction, one literary criticism — what would they be?

Poetry: either Jude Nutter’ s soon to be published “Dead Reckoning” or Teri Grimm’s soon to be published “Becoming Lyla Dore.” Fiction: any collection of Somerset Maugham’s short storied. Non-Fiction: Ross King’s “The Judgement of Paris.” Literary Criticism: any collection of essays by Larry Levis or David Wojahn.

What was your most keen interest between the ages of 10 and 12?

Reading anything I could get my hands on.

At what point did you discover your ability with poetry?

Don’t know that there was a moment when I discovered it. Working in business and technical positions I didn’t encounter poetry until I came across a Ted Kooser poem in his weekly “American Life in Poetry” column. I thought I’d like to try it so I started writing about what I was seeing and hearing around me.

Do you have an ‘engine’ that drives your artistic practice, and if so, can you comment on it?

Basic curiosity. If something captures my interest — why a turkey keeps following the same path through the wildflowers, why some types of snow stick to a tree trunk, and the like, I want to understand it — but understanding is not complete until I can put it into words.

If you were to meet a person who seriously wants to do work in your field — someone who admires and resonates with the type of work you do, and they clearly have real talent — and they asked you for some general advice, what would that be?

Write every day, carry a notebook everywhere and read, read, read.

Do you have a current question or preoccupation that you could share with us?

Currently interested in creating braiding in narrative poetry. Jude Nutter and Li-Young Lee are terrific at this.

What does the term ‘wild culture’ mean to you?

It is our interaction with the natural world and that world’s interaction with ours. When a particular doe beds her fawn down on the slope looking down into our kitchen, I think of it as them in their habitat watching us in ours.

If you would like to ask yourself a final question, what would it be?

How do we move from exploitation to stewardship?

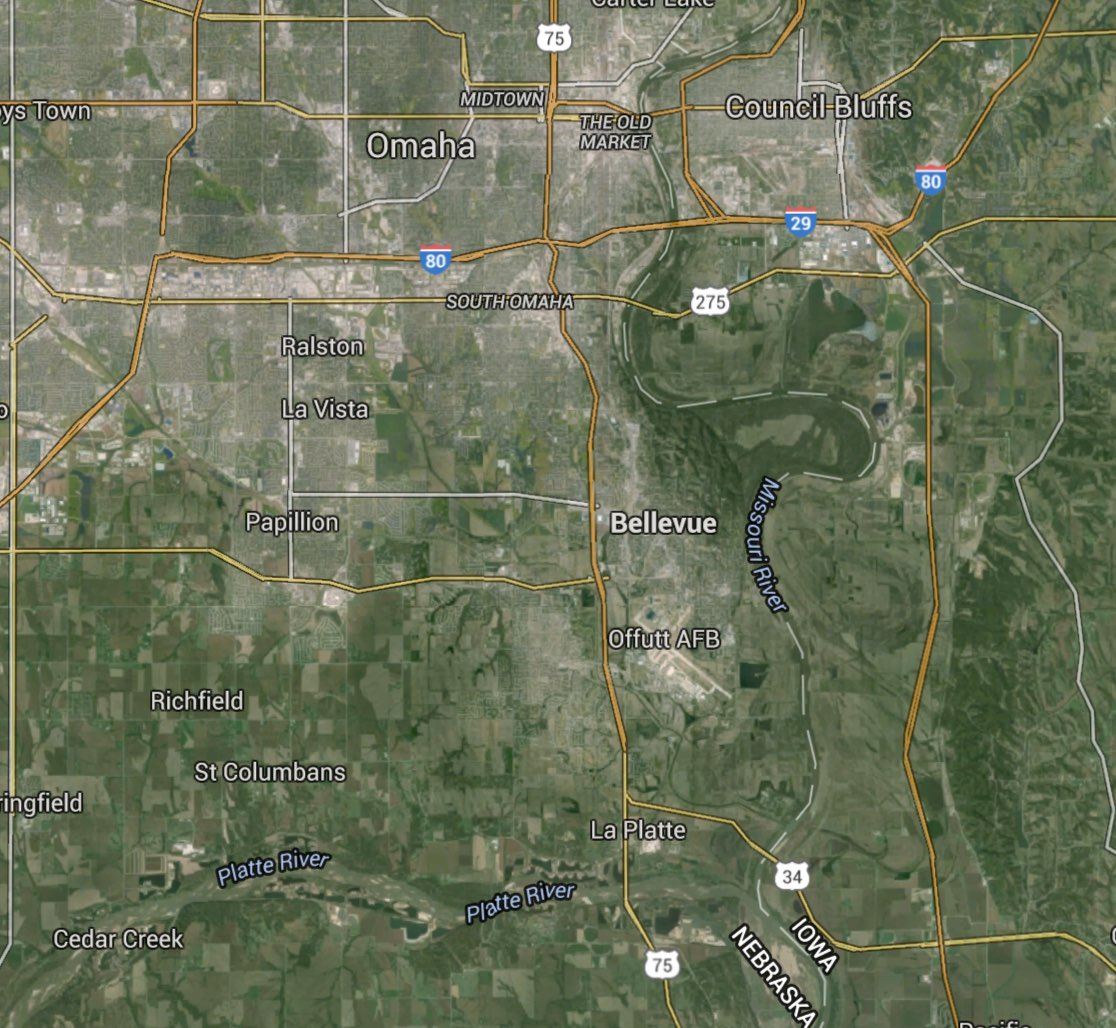

JOHN HICKS is a retired Army officer, retired insurance agent and consultant, and retired business analyst for computer systems. His work has been included in a friend’s poetry anthology and at two of St. Louis Poetry Center’s Poetry Concerts. He lives in Bellevue, Nebraska, just south of Omaha, between Fontenelle Forest and a watershed that runs down into the Missouri River.

Add new comment