At home with the other.

Intertwined: From Insects to Icebergs

By Michael Gross

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024

For boomers with an ecological habit of mind, there was no more an eloquent call to arms than Rachel Carson’s 1962 classic, Silent Spring. Even if we only had the rumour of it, the chilling title said it all. Carson’s alarm bell led to the gradual banning of the pesticide DDT. Now, we know much more about how industrial civilization poisons the biosphere, yet new human assaults on nature’s defenses continue unabated.

There are many excellent books about climate change, toxic legacies and all the environmental issues under the sun, but it is a rare science writer who can deliver the bad news within a narrative of profound and infectious reverence for life. Michael Gross has this deep biophilia, and his new book, Intertwined: From Insects to Icebergs, is a mind-expanding pleasure to read.

Framing ecology as the driver of diversity, he defines it as “the need to eat and avoid being eaten.”

Initially, the book is daunting. Is this a textbook? In the first twenty pages it seems that it may get bogged down in the density of a science nerd deep dive. Explaining the role of lichens in early evolution, Gross is heavy on specialized tech-biochem-agro-botany terminology (cyanobacteria, etc.). However, the jargon serves his thesis, to inspire a deeper understanding of the troubled web of life in our time.

Gross addresses the controversy around plant cognition, an idea that has only recently been taken seriously beyond the realm of J.R.R. Tolkein’s Middle Earth. He appreciates the spread of these ideas in popular culture, but is concerned that books like The Hidden Life of Trees may popularize unhelpful notions of plants as animals. Some interactions between plants and animals are indeed quite astonishing, such as orchids that mimic the pheromones of female insects to attract males. “This deception is so successful that copulation attempts are frequent, and the insect’s misdirected energy secures the critical step of pollination without yielding any reward for the pollinator.”

He offers a fresh perspective on the myriad paths by which the evolutionary hunger games have led to the marvellous diversity of species. "Fish learned to walk, and dinosaurs learned to fly, essentially to avoid predators.” Framing ecology as the driver of diversity, he defines it as “the need to eat and avoid being eaten.”

Gross mines the scientific literature for the interesting discovery, insight or conclusion to share.

He leaves the reader to puzzle out dozens of new terms — epibiont, archaea, hexactinellids. What at first seems overly academic unfolds as a legitimate way of following the meandering paths of human knowledge accumulation, to reveal the ‘aha’ moments when these paths intersect to reveal the mysteries and profound subtleties of life.

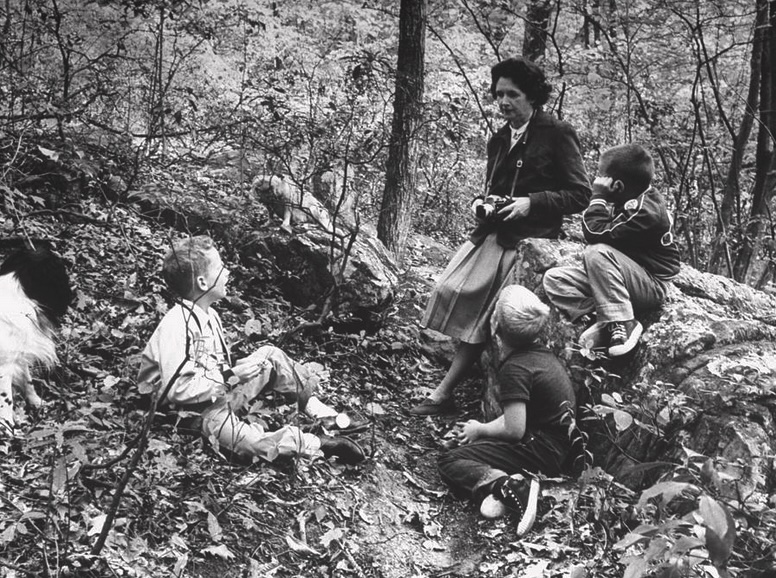

Rachel Carson, from a Life magazine feature with photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

Rachel Carson, from a Life magazine feature with photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

A chapter is dedicated to how insects rule the world. Part of the reason the class of insects has over a million described species is that they suffered fewer losses during the last mass extinction that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs and so many other life forms. “Thus, while much of the biodiversity we see around us, including birds and mammals, has only had around 66 million years to diversify, insects go back more than 410 million years.” While revealing the myriad roles of insects in ecology, from pollination and soil improvement to providing food for other species, Gross points out the threats they face from habitat loss, pollution and climate change and the consequent threats to human well-being. “As we live on a planet of insects,” he warns, “we’d better understand how it works.” Who knew that spiders worldwide devour more biomass of insects (400-800 million metric tons/yr) than the total meat and fish eaten by humans annually? We can draw inspiration from the complex adaptations of colonies of ants and termites to changing habitat and climate conditions.

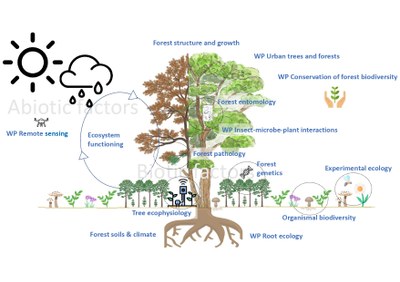

Moving from animals to forests, Gross describes the remarkable case of the Gingko tree, saved from near-extinction by gardeners in ancient China. After the last ice age, one small pocket of gingkos survived. This lovely tree with its male and female forms, and its heart-shaped leaf, might have disappeared if not for the efforts of horticulture to protect and spread it across China and around the world. Understanding the mobility of tree species is key to preserving diversity in the new long emergency of climate change. “Forests are a key element of the climate crisis,” explains Gross. He calls for us to change from the forest management approach of aggressive extraction and to learn from indigenous practices of sustainable cohabitation. “Maybe it is time that our allegedly advanced civilization stops inflicting its business model on Indigenous forest-dwelling populations and asks them for advice instead.”

To explore the threats of extinction due to hunting around the world, Gross starts by describing the ways that migrating birds are harvested for food every year as they pass through southern Europe and the Mediterranean. Despite bans on hunting, there is still a combination of wilful ignorance (aka, tradition) and lack of enforcement. In the fall of 2016, for example, trappers on Cyprus killed 2.3 million birds. Elisabeth Kolbert’s excellent 2014 book, The Sixth Extinction explores the widely recognized (and debated) prediction that we are well on our way toward the next mass extinction (measured as 75% species loss). Whereas the last one was caused by the massive asteroid that formed the Gulf of Mexico (so named for over 400 years), the asteroid this time, Gross says, is us.

What we have the great fortune to be amidst . . . Tom Thomson. 'Path Behind Mowat Lodge.' 1917.

Starved for some good news, it is a relief to know that the oceans are not yet as badly affected by human habits as is the land. Gross celebrates the recovery of some whale populations, and explains ongoing efforts to make coral reefs more resilient through the breeding of super corals. Studies of deep water mesophotic (twilight) coral ecosystems that live in conditions of less heat and light are also encouraging.

About 130 years after Darwin noticed that geographical isolation led to the divergence of species (between the Galapagos islands and the mainland) E.O. Wilson and Robert MacArthur came up with the term “island biogeography”, the study of the connections between geographic and biological change. These fundamental concepts of “islands of life” now form the basis for all studies of biodiversity, which in turn makes the syncretic, wholistic insights about biodiversity in Intertwined possible.

Humans are the most invasive species of all, and we are responsible for most of the spread of invasive species worldwide. Some are benign, but often invasives compete with indigenous plants and creatures, while providing no nourishment for the local insects and birds. Looking at the ways that people have carried invasive species with us where ever we have gone, Gross treats us to a long discourse on the adversarial history of Tom and Jerry, cats and mice. The fascinating tale of Mus musculus domesticus (the house mouse) goes back to evidence of their scavenging in Neolithic settlements 14,500 years ago. Domestic cats enter the archeological records much later, about 7,000 BCE. Egyptian cats rode the marine trade routes of the classical era, likely living on mice aboard trading ships. Cats of Egyptian ancestry travelled with Vikings as far as northern Germany. “Studies of ancient cats and mice have shown up the curious history of how this predator-prey couple followed humans and their cereals around the world.”

One does not expect to be interested in vultures, but Gross makes them astonishing.

Half way through the book the generalist reader learns, almost by osmosis, a lot about research methods, about how science works. This has so much to do with the power of communication and sharing among many independent scientists across disciplines and, crucially, across borders. For example, Gross explains the relatively new discipline of acoustic monitoring methods — sound monitoring to track biodiversity loss—what kind of data it yields, how it is interpreted, and how the findings are applied. Sound monitoring seems obvious, yet brilliant. All of us who walk regularly out in nature do it, particularly with reference to bird song from one season to the next. This of course brings us full circle back to Rachel Carson and her early warning about the potential for a silent spring.

The book is packed with revelations about aspects of the natural world that may never have crossed your mind. One does not expect to be interested in vultures, but Gross makes them astonishing. It helps if they are called by their more noble name, condors. Their feats of long distance flight can carry them on migrations as far as 12,000 kilometres, and on an average day they can fly 360 kilometres. To achieve this they ride the thermals, flapping their broad wings as little as 1.3% of their recorded flight time.

Arctic ice tells the truth about climate change, and the truth from climate scientists is that the arctic ice is dying. “In summer, even at the North Pole, it was characterized by extensive melting and erosion,” according to Markus Rex of the Norwegian Alfred Wegener Institute. “The ice is only half as thick as it was 40 years ago, and the winter temperatures… nearly ten degrees warmer than what Nansen experienced on his ground-breaking expedition over 125 years ago.” The Arctic is the fastest changing region due to global heating. Gross presents the scientific consensus on climate change evidence and predictions. The statement that strikes hardest in the midst of anti-immigration fervour in America and Europe is that “toward the second half of the century, billions of people will be forced to desert their homelands in tropical regions that will no longer be habitable.” Climate change is survivable, but closed borders will kill people.

“Forests are a key element of the climate crisis,” explains Gross.

Intertwined is by turns delightful and harrowing to read. Moving toward his conclusions, Gross offers us a close look at the plastics in our oceans and our bloodstreams, and the emergence of pathogens that threaten to overwhelm our health care systems. He goes all the way toward the possibility of the self-inflicted demise of human life. Gross can’t help it, it’s how his fine mind works. The last word is left to Australian scientists Maggie and David Watson, who write of the inevitable disappearance of humans from the face of the earth they have so mistreated. “As a crisis discipline, conservation biology takes a toll on its first responders, routinely confronting us with accelerating extinctions and a society increasingly detached from wildlife and nature.” If there is hope in the long term, it lies in the knowledge that abundant life forms will outlive humans for some billions of years before the sun turns into a red giant. ≈ç

RELATED LINKS

Reviews of The Hidden Life of Trees from The New Yorker and The Marginalian

Sixth Extinction: Wikipedia, Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker.

Alfred Wegener, Institute research expedition Arctic — Mosaic.

Acoustic monitoring:

• For Conservation and Ecological Research

• Technologies for Ocean Acoustic Monitoring

Condors

Andean Condor Can Fly 100 Miles Without Flapping its Wings

CHRIS LOWRY is a media producer and singer. His most recent documentary feature is Rebel Angel, about the Canadian literary and culture critic, Ross Woodman. As part of the original team that created the print version of The Journal or Wild Culture in 1986, he served as Senior Editor from 1986 to 1989. He lives in Toronto where he performs regularly with his band, The Cool Blue North. View Chris' site.

Add new comment