"It is a place where you can create relationships and test yourself and feel you are making a contribution to the team and the world around you." Photo (inset) by Kelly Mohun. [o]

Our goal is to understand how leadership today is different than it was, but first tell me what you and your company do.

GUY BEAUDIN You can think about what we do in two categories: assessing talent and developing talent. In assessing talent we help to identify the right individual for the right job when an organization is looking to hire or promote someone into a senior executive role. The people who hire me understand the importance of talented leaders and of their ability to manage the people around them effectively to achieve outcomes. We do that through psychometrics, interviews, sometimes via 360 processes. We also help organizations develop talent, either through individual coaching, through working with senior teams, working with boards of directors. A big component of what I do now is around CEO succession, so that means working with boards of directors as they look to develop internal talent for future CEO succession; and also to eventually help select the right individual for the job.

Since we’re now in a situation where trust in society and its institutions is crumbling, the employer now has a new responsibility — and a different role to play.

WHITNEY SMITH So the TV show Succession would be of relevance.

BEAUDIN Completely. It's an extreme example, but if you're reading what has been happening at News Corp. lately, it's pretty much the same scenario. That said, none of my clients are that wacko. But that's a good example of the kind of things we do. I work with boards and CEO, I get to know their teams and the talent in those teams, then, if I do my work well, I become an adviser to the CEO and the top executives in the organization. In that way I become a third party to discuss the challenges they're having — with their own leadership and the anxieties they might have in delivering against expectations of a wide range of — sometimes competing — stakeholders. I'm not a therapist, but the conversations are not trivial once I get to a place of trust with my clients.

SMITH So, you’re dealing with a person who behaves as a professional with a high level of skill in their field, but also has a particular personality and psychological make-up that plays into that work.

BEAUDIN Exactly. Though I am trained as a psychologist, I think of myself primarily as a business advisor who focuses on talent. Interestingly enough, I've worked with some clients for five to ten years and they don't even know I'm a psychologist. And I bring ideas and concepts of psychology to bear in a work environment with individuals who would never reach out to talk to a psychologist.

SMITH How do you get the information you need to be able to help them?

BEAUDIN We use a number of psychometric tools that allow me to understand people's personality that show us how they react under stress, what are the things that motivate them, and how they are an obstacle to themselves. I also get a lot of my information from multiple conversations I have with a range of individuals within the organization. Some leaders I’ve met over the years regard leadership solely as an economic transaction — I’m going to pay you X, you're going to do Y, and if you're not doing Y, I'm going to fire you. Those people exist, but they don’t hire me.

SMITH Who hires you?

BEAUDIN People who know that it's a very difficult endeavour to lead well. And, if they get someone like me in to understand enough about their business — how they make money, what their markets are, who their competitors are, what their strategy is, what they're trying to achieve as an organization — then I can help them figure out what they need to do as a leader to get the right outcomes. I can also help them understand how they get in their own way, what are their blind spots that prevent them from having the kind of influence and impact they want to have. By the way, this is not just about getting financial results, though that is a part of it, it is also about creating an environment that is engaging and fulfilling for the people on their teams.

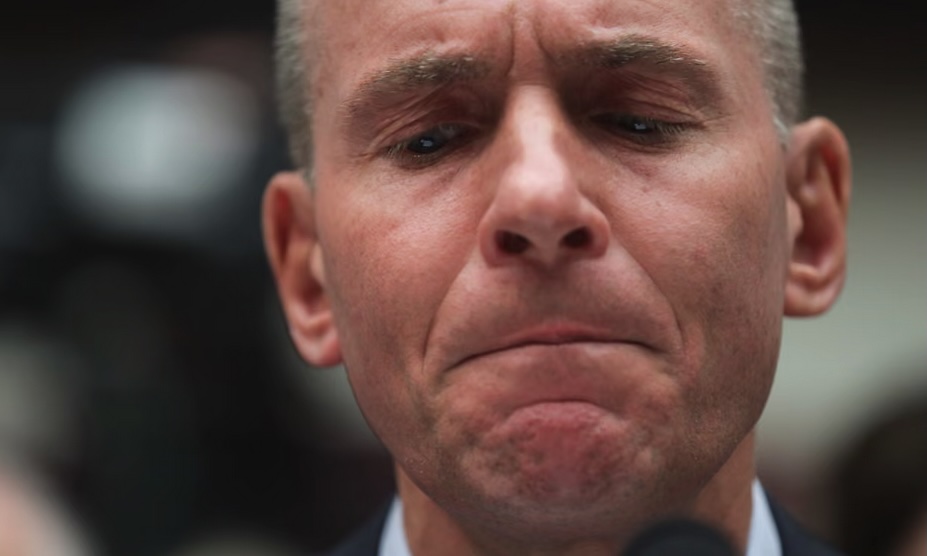

Ousted CEO Dennis Muilenburg, 55, who worked at Boeing for his entire 34-year career, was widely criticized for failing to properly acknowledge the impact of two crashes on grieving families. He had also been accused of appearing to mislead the aviation regulator. [o]

SMITH I see how that part of your job works, that you get to know what the CEO is dealing with in their business — what things confront them and what they must decide for their organization’s benefit. Let’s make a shift and look at styles of leadership that have emerged in the last few years as alternatives to more traditional ways of leading.

BEAUDIN Since I started this work in the mid-1990s, I’ve seen a couple of central themes around leadership evolve. When I studied organizational psychology, one of the key things we looked at was ‘command and control leadership’ and the studies of Taylor from the 1950s. This model features a kind of archetypal, all-knowing, all-seeing leader who makes all the decisions. But recent changes in the world, and in technology and society, meant such leadership was to doomed for failure. I don't know the story about the CEOs of Boeing or Volkswagen when very unfortunate things happened under their watch, but I bet that the CEO or his team in some way exercised a form of leadership where it became detrimental to your career to bring bad news to the folks at the top. In those situations, mostly, the underling is encouraged to focus on the positive and bury the negative. If an employee at work thinks, I'm not really sure about that, then they go home at night and worry about it, but the next day they don't put it in their deck, that is where trouble starts. The CEO doesn't need to say, don't bring me bad news, it’s understood. The instinct for self-preservation, and not being yelled at, is powerful. So a fundamental element of how leadership has changed in a world of increased complexity is that the CEO is an orchestrator of talent rather the all-knowing, command and control leader. One of the biggest risks a leader needs to guard against is losing touch with what is really happening inside their organization, and good leaders do that by inviting multiple and dissenting points of view.

SMITH Do you have an example of a CEO facing a potential threat to his leadership that you became aware of because his employees confided in you?

BEAUDIN I was working with a CEO who was exactly what we’re describing here. If you came to him with bad news at a meeting, he'd chew you out in front of your peers. As a result, everyone learned not to challenge him. It was a financial services organization — in 2008 where they kept just creating new vehicles to try and make it work — and one of their investments was in deep trouble. Plus, there were early signals that the company was running out of cash and they’d have to declare bankruptcy. In the hopes that they could shore up this particular investment, the team was not disclosing what was happening. As a result, everything collapsed. They had to declare bankruptcy and write off an enormous investment, and the CEO's reaction was to rail against the incompetence of his team. I went to him and told him there was another way to approach this. You have created a culture where people don't want to bring you bad news for fear of the emotional price they need to pay — and out of a desire to keep their jobs.

Clearly this individual did not want to be the cause of people hiding crucial information. But his concept of how to lead and get them to pay attention was to dole out negative consequences. We all have our own self-concept of what good leadership looks like; his self-concept, borne of a real deficit of humility, was exploding on him. My job was to get him to understand the consequences of his leadership style. He heard me out and he started by going to everybody on the team and saying, I recognize that part of what happened here was due to my own behaviour. How can we make this work?

SMITH Let’s pretend that I'm that guy before you have the first key conversation with him. How do you start? Pretend I’m him.

BEAUDIN How I approach that particular conversation would be fairly typical of how I would do it in similar situations. So Whitney, I've been talking to your team, around the questions of how they are perceiving your leadership, what's working and what isn't. Let me start with a list of things that you're doing well. (So I go through that.) Now, there are some difficult things I really need you to talk about. And, it’s going to be hard for you to hear because I don't think you're expecting it. I've heard from multiple people and these people see you as arrogant. This is expressed by you always having the last word, never asking for people's advice or opinions, and shooting people down when they have a point of view that is different from yours. Believe me, there’s still enough goodwill inside the organization to make a change, but we're going to need to address this fundamental trait for you to be successful, which is, in a nutshell, how you are coming across to your team. Now, I've known you long enough to know that's absolutely not your intention. Your intention is not to be a bully. Your intention is not to minimize them. You're under a lot of stress, you're trying to get the work done, you're under pressure from your board and from your investors, all that is, understandably, making things difficult for you. But I can tell you right now, if you can continue along these lines, you will not be successful in this role.

SMITH Strong medicine.

Employees leaving their offices following the collapse of 158 year-old investment bank Lehman Brothers. [o]

BEAUDIN Yes. And that is a decisive point. If they engage with me and want to learn more about what to do, then they have a good chance of being successful. If they are defensive and externalize, then there is little possibility of them making the necessary changes.

SMITH As you’re saying this, as you're talking about a leader’s style, I’m thinking about bullying. Would you say that in the control and command tradition, bullying is just another method to get things done, to get people to pay attention.

BEAUDIN Yes. Very few people want to be a bully — or show up to work with the intention of wreaking havoc. “Today I'm going to let people have it.” But when a leader doesn't have the tools or resources to influence others to get things done, they can resort to bullying to achieve their goals, often out of frustration. Leadership is really hard, and many people who are leaders shouldn't be. Assuming there's no kind of character flaw there, these people merely lack effective ways to talk to their employees and bring them around — and to get them organized in a way where they can achieve what they want to do. Sure, there are psychopaths out there, people who derive pleasure from having authority over others, but in my experience that’s pretty rare. It’s mostly the mediocre leader who drifts into bullying.

SMITH There seems to be a proliferation of bullying charges in the workplace in recent years, more so than a decade or two ago. Would it be fair to say that younger generations of workers have different expectations of their leaders than we had when we were young?

BEAUDIN Very much so. Actually, there are several interesting pieces of research out there that are useful in considering that notion, the best of which is, in my opinion, the Edelman Trust Barometer. They survey hundreds of thousands, maybe even millions, of people from all over the world on an annual basis around a couple of topics related to the subject of trust in institutions — government, journalism, media, industry, NGOs, and so on. If you look at the trend lines, there is a tremendous erosion of trust in most societal organizations.

The credibility of governments, for example, has been battered by a few things: political polarization, a perceived failure to address societal problems, and a sense that it is not equipped to handle the challenges of a rapidly changing world. Similarly, the media has faced a crisis of confidence, largely driven by the proliferation of misinformation and the rise of social media.

However, what remains relatively robust is trust in one's employer. This has interesting implications for leadership in our times. Since we’re now in a situation where trust in society and its institutions is crumbling, the employer now has a new responsibility — and a different role to play — in maintaining the social cohesion needed with everything that's going on in the world now.

This became very acute during the aftermath of the George Floyd situation. Employees turned to their employers and asked, “What are you going to do about this? What stand are you going to take?” This is particularly present with a younger generation of employees who want a work environment and culture that's meaningful to them. And much more important to this generation than it was for you and I where our approach to work has instinctively been transactional. It is not at all that way for the younger generation of leaders. We are seeing this happen now as well over situations like Gaza and Ukraine which a generation ago might not have seeped into organizational life as much as it does now.

Older generations are much more conventional in their view of how work gets done, which is often at odds with expectations of younger people.

SMITH Let me take a shot at a possible connection here. Does this more traditional leadership style approach the bullying question in a roundabout way? That is, in cases where leaders are boomers or a bit younger, or at least of that ilk, who practice a directive command and control style, might that directive style sometimes comes off as bullying, and therefore not acceptable to a younger generation? And I’m not excusing bullying. I’m asking if it’s the result of a clash of styles — a clash borne of generational differences.

BEAUDIN That is a bit of a generalization, but it's a fair question to ask. I refer mostly to the notion of the responsibility a leader possesses in creating or maintaining social cohesion in light of the erosion of trust in other institutions. The importance of the leader of today is to examine their own values, their own biases, and how their upbringing has influenced their view of society. That’s new. And very different from the old way of thinking about leadership. By the way, this generational shift has manifested itself very much as well in the differences in attitude to the post-pandemic ‘return to office.’ Older generations are much more conventional in their view of how work gets done, which is often at odds with expectations of younger people.

SMITH This younger generation’s reaction to the MeToo movement and George Floyd’s death was partially responsible for a fruition of programs addressing diversity, equity and belonging. Now, at least in the United States, these programs have become cannon fodder. But they are fundamentally about respect for the employee as an individual.

BEAUDIN Yes. And though ‘officially’ these programs are in retreat now, I'm hearing from the leaders I work with that they will continue with those practices, but we'll just call it something else. By and large, they still believe in the importance of creating an environment where everybody's role is valued according to their contribution, without regard to other traits or characteristics. Why? Because they understand its value, and they don’t want people inside their organization calling them on it. It’s one way for them to strive for the cohesion they know is necessary.

SMITH So we're still working on creating a culture that observes these dynamics.

BEAUDIN I’d say so. One of my colleagues, Cristina Jimenez, saw this coming and was at the forefront of it. We have a practice we call ‘belonging.’ It's not called diversity or inclusion, but it is about the need to create a place of belonging for everybody in the organization — as well as the style of leadership required to create that kind of culture. The post-COVID era brought a fragmentation of society and increased isolationism. Again, particularly with young people and partly due to technology. But I continue to believe, as I did when I started this work, that there is a place, even more so now, for organizations to create a place of belonging, a place of meaning where you can create relationships and where you can test yourself and feel that you're making a contribution to the team and the world around you. More so than ever.

Photo by Kelly Mohun.

SMITH A final question. What do we expect from our leaders today — not so much as professionals but fellow human beings — that we might not have in the past?

BEAUDIN To be a successful leader today you need to be able to demonstrate authenticity and humility. People get up and leave organizations where they feel their leader is not being authentic. Going back to one of the things we talked about, not every leader is able to make the shift. One leader said to me, “I don't know what to say about George Floyd, I don't know what to do, I'm afraid to say the wrong thing.” I said, that's what you're going to say. You’re going to say: “Listen, I know this is a very emotional and disturbing time for many people. I don't know what to say to you today, but I will educate myself and we will have a position on this in a way that meaningfully reflects what is happening here.” He got huge credit for that. If people see you as real, as genuine, as ready to learn, as being humble and human, they are more likely to trust you will get to the right place.

SMITH As opposed to, I'm strong and we're going to get through this, yet having no idea how to do that.

BEAUDIN Or read what your PR department wrote for you. That's what the PR department wanted him to do, just read the prepared statement. He said, I just can't. I said, you'll find a way, you'll eventually find the words. But now what you have to say is, I don't have the words. These are the sorts of thing that are making leadership ever more challenging. How you deal with what's happening in the environment or with climate change, or the tremendous inequality in society, and so many other circumstances that are way beyond how I make this widget and how much can we sell it for. As a leader, you need to navigate all these other things just to be able to get to that widget you can put on the market. You can't ignore all these forces in the world. There are too many people coming into the work force that won’t tolerate it. ≈ç

GUY BEAUDIN is a senior partner at RHR International, established in 1945. Fluent in English and French, Guy has authored numerous articles and publications on leadership topics. He was a long-standing director of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and currently supports a variety of nonprofit CEOs and organizations with pro bono coaching. He lives in Toronto.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher/Editor of the Journal of Wild Culture. One of his keen interests is understanding how people gather to achieve shared aims, and how effective management and leadership skills help to get things done while helping the participants lead nourishing lives.

Add new comment