"It’s a protected national park, and also Ecuador’s touristic cash cow." [o]

One of the world’s great civilizations, the Maya, flourished in southern Mexico and parts of Central America for more than three thousand years. From about 2000 BC until the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century, various Mayan centers rose in their far-flung territories — in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Maya peoples developed a hieroglyphic writing system, as well as ornate arts and sculpture designs, architectural innovations, complex mathematics and a detailed calendar based on their highly sophisticated astronomical calculations. Over the centuries the Maya withstood conquest by other indigenous peoples, sometimes for prolonged periods, and the systematic destruction of their culture by Europeans.

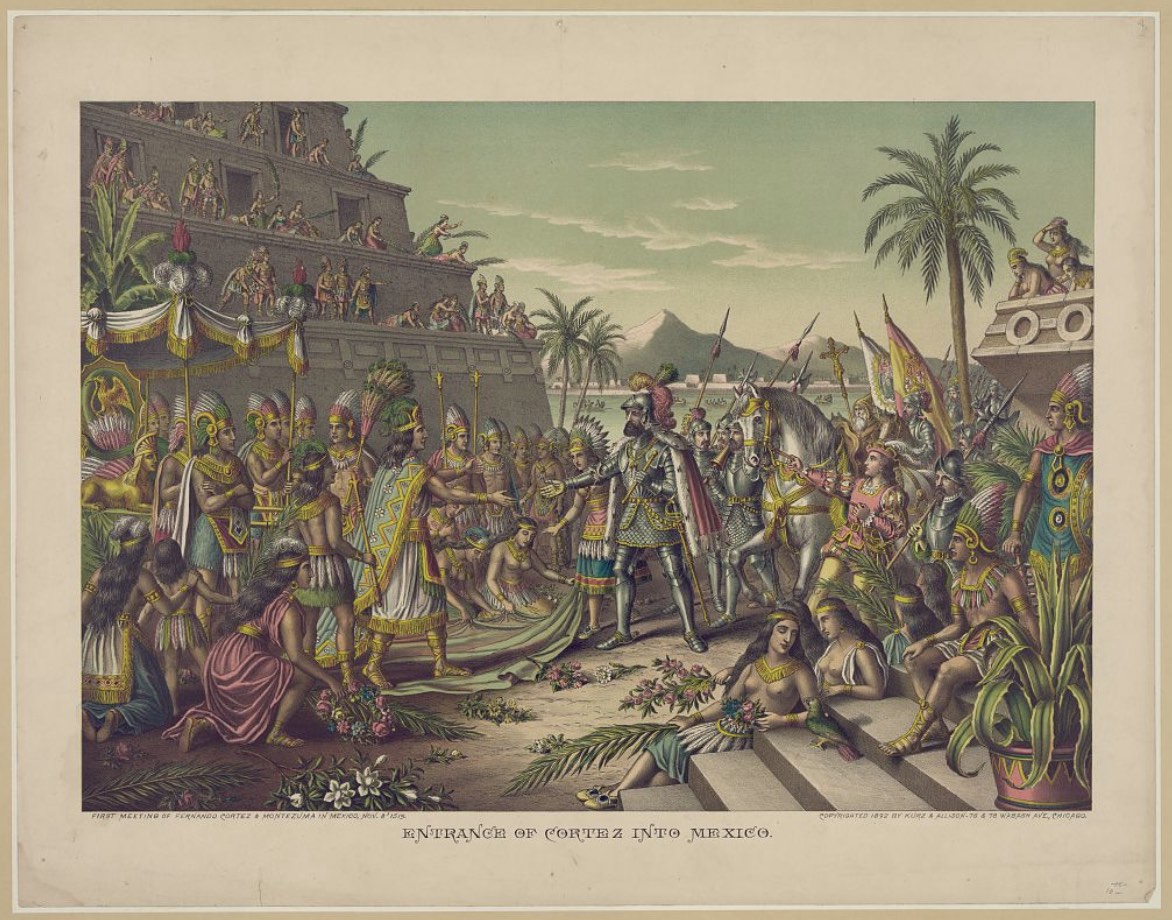

The Spanish demolished Mayan temples, spreading Catholicism and disease wherever they went. The island of Cozumel, off the eastern Yucatan coast, now a destination for cruise ships and scuba divers, was once a sacred site of pilgrimage for the Maya — home of their Moon Goddess where women came to seek fertility. At least ten thousand Maya were living on Cozumel when the Spanish arrived in 1520. But the smallpox they brought soon reduced the native population to a few hundred who were later — forcibly — relocated to the mainland. As Wikipedia succinctly notes: “The Spanish conquest stripped away most of the defining features of Maya civilization.”

But the most grievous threat to the legacy of Mayan culture was yet to come . . .

Despite the best efforts of soldiers and priests, Mayan culture and language persisted in part because some of its population centers were remote, and because some Maya peoples stubbornly and secretly persisted in their beliefs and customs, away from the official gaze. When the Spaniards had taken everything they considered of value, they left the population of subsistence farmers largely to its own devices.

In the nineteenth century the Maya were “discovered” by adventurers, ethnographers and archeologists who romanticized and plundered Mayan sites, including the cenotes, the underground rivers where Maya buried their dead, often laden with gold and jewelry. Mayan treasures — pottery, stone carvings, paintings, codices — ended up in museums and private collections around the world. Not until the mid-twentieth century did Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History organize against this systematic looting and demand the return of their national patrimony.

In 1964, Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology opened in Mexico City. One of the world’s great museums, it features artifacts from the many indigenous peoples of Mexico’s pre-Columbian past, including a generous selection of Mayan art and architecture, a fair portion of it returned from abroad. A visit here is a must for anyone who hopes to grasp the cultural and historical diversity and significance of Mexico’s complex identity.

Though many Mayan pieces had been ripped from their original contexts — from tombs and temple walls in various sites in the Yucatán and elsewhere — at least some had now been repatriated to Mexico. But the most grievous threat to the legacy of Mayan culture was yet to come: in the form of apparent adulation that morphed into a full-blown assault that continues today.

“We came to serve God, and to get rich.” ― Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain [1632]. [o]

In 1967, the Central Bank of Mexico commissioned a two million dollar (US) study about how to attract foreign currency through tourism — partly motivated by the fact that the Mexican economy was in trouble, despite the country’s huge petroleum reserves. Mexico had nationalized all foreign oil interests in the 1930s to create PEMEX, the government oil monopoly. As Mexico industrialized during and after World War Two, PEMEX constantly increased oil production but was unable to meet the ever greater demands. Combined with mismanagement and corruption, the greater demand from inside and outside the country forced Mexico to become an oil importer instead of an exporter.

The only tourist area attracting significant foreign currency to Mexico was Acapulco, a resort that emerged in the 1940s when war eliminated many holiday destinations in Europe. Through private investment and government assistance, Acapulco built infrastructure and luxury hotels that turned it into a jet set “playground of the stars” by the 1950s.

Mexico’s Central Bank, Banxico, had a different touristic plan in mind. Their study identified five areas of Mexican coastline — four on the Pacific and one on the Caribbean — that were ripe for massive investment. Banxico formed an investment agency to create Ixtapa, Huatulco, Loreto, Los Cabos and, as their first project, Cancún, on the Caribbean. The plan was designed not only to attract foreign tourists and their currency, but to provide jobs outside Mexico’s major industrial cities, where desperate unemployed people by the millions were crowding in from rural areas seeking work.

In some ways it seemed an unlikely, even quixotic, idea. The area now known as Cancún in 1970 had a population of about five hundred. Roads on the Yucatán were rudimentary, as were the coastal ports. The few air strips could only accommodate small planes. Banxico proposed to devise and construct an enormous mega-resort zone where only forested limestone plains and low hills existed along a mostly empty coast. Also in that area were several extraordinary Mayan temples, pyramids and cenotes, many of them protected and preserved only because they were largely inaccessible.

For the first couple of decades, things seemed to be progressing well in Mexico’s concocted Caribbean tourist Mecca. Tens of thousands of Mexicans found work constructing and servicing the huge luxury hotels and restaurants. The tax base expanded, public services increased, living standards improved; as as result, foreign currency came rolling in. “From one of the most marginalized regions in the 1960s,” writes Linda Ambrosie in her book Sun and Sea Tourism: Fantasy and Finance of the All-Inclusive Industry (from which much statistical data in this article was taken), “the Mexican Caribbean became one of the wealthiest in terms of GDP per capita in 2000.” Cancún’s new international airport became the second-busiest in the country, after Mexico City, with the most international traffic. Forty percent of all foreign currency generated by tourism nationally is from Cancún.

Map of the Yucatán including Mayan ruins. [o]

But by the late 1990s the significant social and environmental costs of rapid development and the apparent prosperity had become acute and undeniable. Despite liberal federal government subsidies and tourism promotion, income inequality in the region was well above the national average. Insecurity was increasing. School attendance was down. Suicides and teenage pregnancies were on the rise. And the reefs were degrading, partly from pollution and excessive dive tourism, partly from growing cruise ship traffic, which continues to increase. “Cozumel edged out Nassau to become the world’s most popular cruise destination in 2016,” according to a report from the Oxford Business Group.

As the once-clear air suffers from increased motor traffic on the clogged roads, the paths to Mayan ruins suffer from increased foot traffic. Unless you arrive to visit ruins as soon as they open in the morning, you will struggle through crowds of visitors at the once-pristine settlements. The streets of Tulum, a rapidly expanding city as well as a picturesque Mayan ceremonial site, are ankle-deep — and in some places, knee-deep — in littered garbage. Can it be redeemed? There is no sense today that anyone is making any effort.

In 1984, a Hollywood movie, Against All Odds, was filmed using locations on Cozumel and Isla Mujeres, and Mayan sites at Tulum and Chichen Itza. According to IMDB [Internet Movie Data Base] that “was the first time permission had ever been granted by the Mexican Government to use these sacred ruins for a theatrical motion picture.” Visitors to those areas who see that movie now will be shocked at the changes that have occurred there in the past 35 years. If they can take their eyes off Rachel Ward or Jeff Bridges . . . movie viewers can behold natural and architectural beauty that no longer exists in reality.

In many tourist destinations in the Yucatan, human interaction has become commercialized and degraded. During the Christmas holiday, the peak of peak tourist season, many of the expensive guided tours to Mayan sites or natural wonders are abbreviated, without any advance warning or reduction in price, simply so that tour operators can entertain the highest possible volume of tourist traffic. Visitors only find out about the foreshortened experience in the middle of it, after they have paid. Tourists, vendors and service providers are mere commercial entities. It’s all about the money. Faces and identities of locals and visitors disappear in the mercenary blur.

Do you go there as soon as possible to experience the unique ecology for yourself before it disappears forever?

As often happens in situations of economic opportunism, the rush to cash in on the tourist dollar motivates local merchants to render once-unique and charming landscapes into tacky pizza-T-shirt-tiki-bars and generic high-end hotels. And they’re not slowing down. Sure, this is a problem in many places, not only the so-called “Riviera Maya” (the bogus term that boosters use to describe the ongoing metastasizing development down the Yucatán Peninsula).

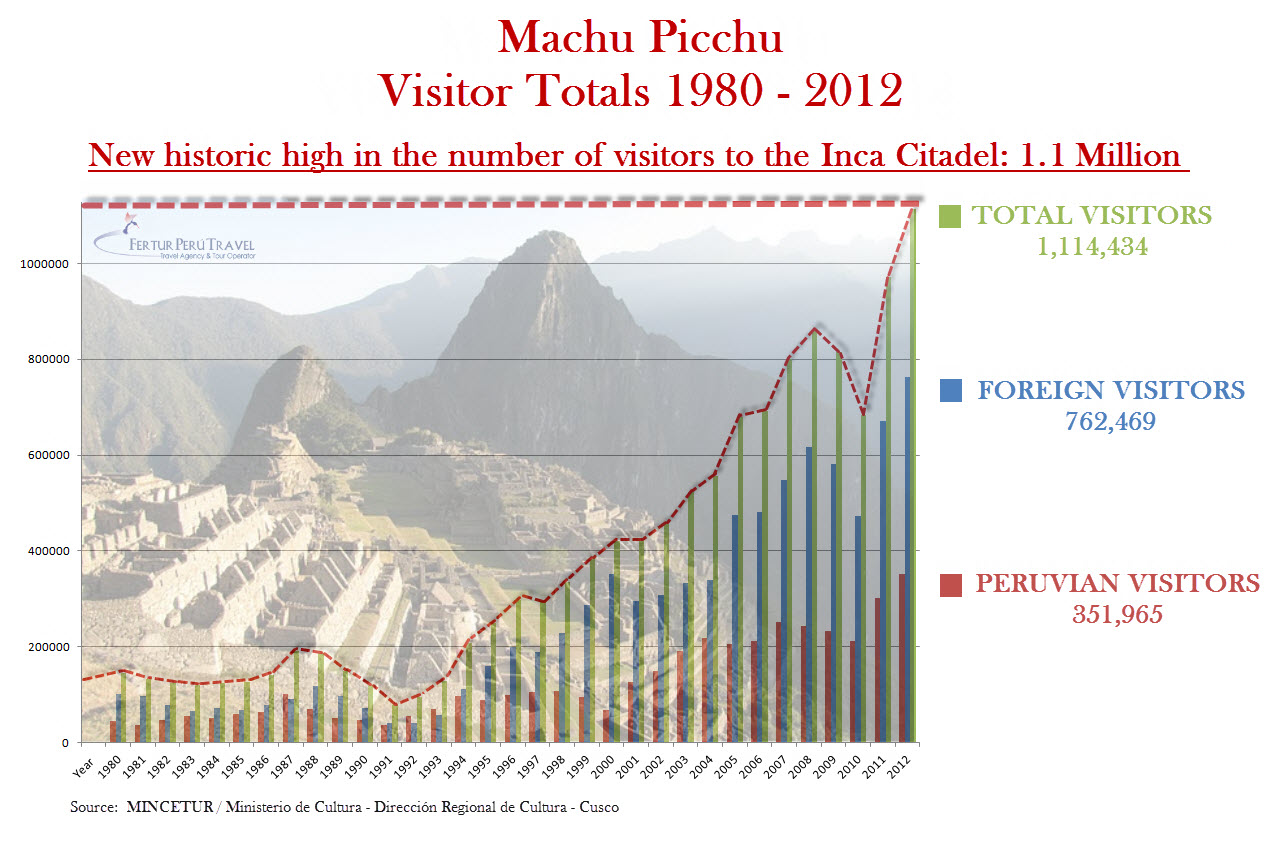

Commercilization and over-development on the Yucatán represent a modern travel equation: the value of a unique destination decreases in direct proportion to the number of visitors it attracts. Machu Picchu is struggling with this problem, as are Iguazu Falls and many U.S. national parks, prisoners of their own popularity. At this point, Cancún has exceeded its acceptable limit. There is less and less to see: reefs with no fish, jammed and littered beaches, coasts with diminishing beach access, and Mayan sites too crowded to actually view, let alone appreciate contemplatively. Just too damn many people . . .

The Mayan calendar, a detailed and highly accurate record, spanning centuries, ended at 11:11 a.m. on December 21, 2012. Some excitable New Agers thought the Maya were prophesying the end of the world. But perhaps the Maya just knew it was the end of their world — or maybe they just ran out of rock. (Centuries ago, when what is now a sprawling resort was a raw, barely inhabited wilderness, it was the Maya people who named it Kankun, meaning “nest of snakes.” In some ways — considering the hustling and price-gouging going on there now, not to mention the declining quality of life for the locals — the term seems prescient.)

World travelers these days must struggle with what has been called the Galapagos Conundrum. Situated off the coast of Ecuador, the Galapagos Island group spans both sides of the Equator. The northern islands get the warm Panama current, while the southern islands get the cold Humboldt current. This variation in water temperature causes variations in habitat and evolution of species of animals who live in these islands. As Darwin discovered, the same species of birds and reptiles differ markedly on different islands, though in actual distance they live not far from one another.

The Galapagos Islands are a unique world unto themselves, with creatures that exist nowhere else — with great variety among, and within, different species. It’s a protected national park, and also Ecuador’s touristic cash cow. In order to preserve it, the country is trying (as Peru is with Machu Picchu) to limit the number of visitors who tread upon the sensitive environment — while also making the maximum possible profit from its popularity. Peru has limited visiting hours and drastically increased entrance prices to the Incan remains at Machu Picchu, but there is no letting up on the numbers of visitors who still come from around the world to feel the magic firsthand.

So the Galapagos Conundrum is simply this: Do you go there as soon as possible to experience the unique ecology for yourself before it disappears forever? Or do you refrain, in order not to contribute to the degradation of a sensitive site, so that it may continue to exist?

Sadly, that is a riddle too late to wrestle with on the Yucatán Peninsula. Nor were those questions the Central Bank of Mexico, in hindsight, had the foresight to anticipate. But Cancún may have more to worry about than pollution and the school drop-out rate. There are signs that the Mexican drug cartels are starting to muscle in on Cancún’s tourism industry as they did in Acapulco, demanding protection money and turning it into a ghost town, with lots of murderous violence.

That would make its Mayan name, KanKun, the nest of snakes, a genuine prophetic curse. ũ

* Linda M. Ambrosie, Sun and Sea Tourism: Fantasy and Finance of the All-Inclusive Industry, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015, p. 111. Most statistical data in this article are from Ambrosie’s book.

JAMES MCENTEER is an American journalist, writer and frequent contributor to the Journal of Wild Culture who has been living in Quito, Ecuador for the last seven years. His most recent book is Acting Like It Matters: John Malpede and the Los Angeles Poverty Department.

Comments

Oh my. I visited Merida and

Oh, my. I visited Merida and Chichen Itza in 1969 and completely and absolutely fell in love with the Mayan culture, the incredible Chichen, the food — but not the stifling summer heat and humidity! The weather did not dampen my gut reaction, my appreciation, my love for these people. I still have a huipil I purchased from a lady in a town/settlement with no name. The gorgeous handiwork around the neckline still is gorgeous. While I am saddened by what has happened, I still honor these amazing people. Thank you for the article, painful as it is for me to read.

Add new comment