Back in 2009, a handful of adventurers set out on a hike. “Beyond the gates, they announced, “out into the wilderness, is where we are headed. We shall make the pilgrimage to the poet’s Dark Mountain, to the great, immovable, inhuman heights which were here before us and will be here after, and from their slopes we shall look back upon the pinprick lights of the distant cities and gain perspective on who we are and what we have become.”

Three years, a couple of books and a website later, the third major instalment of Dark Mountain has arrived, via printers and postmen, on the laminated, denatured wood of my office desk. Like a snowball gathering twigs and heft as it rolls back downhill, the project has grown in size and ambition since the publication of the Uncivilisation manifesto that marked its timely origins. Now, in a kind of backwards glance over the shoulders, this third book is centred loosely around the idea of ‘home’.

Across poetry and fiction, interviews and essays, art, photography, anecdotes and illustration, a bleak picture of contemporary civilisation emerges. The central thrust of the Dark Mountain project is that we are currently living through a period of crisis. As the manifesto makes clear: “All around us are signs that our whole way of living is already passing into history.” This latest chapter posits itself as an attempt (or series of attempts) to position a concept of home in light of this unravelling.

This manifests itself through, amongst other things, John Rember’s thoughtful discussion of narcissism, rhetoric and skiing; NR Alcock’s account of evictions caused by Zaha Hadid’s infuriatingly flawed masterplan for Bilbao; and Nick Hunt’s shimmeringly evocative short story – ghosts of absent, lingering pasts – that so perfectly closes the collection. Elsewhere, highlights include: the wild poetry of Tom Hirons; David Kernohan’s wryly inventive Schrodinger’s Wife; Andrew Taggart’s idea of humanity’s response to the Flood as an allegory for modernity; the concept of the vernacular in the intellectually engaging (but slightly self-conscious) discussion between Dougald Hine and Sanjay Samuel; and the idea of a broken piano as a kind of image for “our times” in Hannah Lewis’ heavily John Berger-influenced piece on loss and displacement. No longer Coleridge’s Eolian Harp, but a relic of a former time, whose use today is unclear, yet to be decided.

The journey onwards begins here, with this step back.

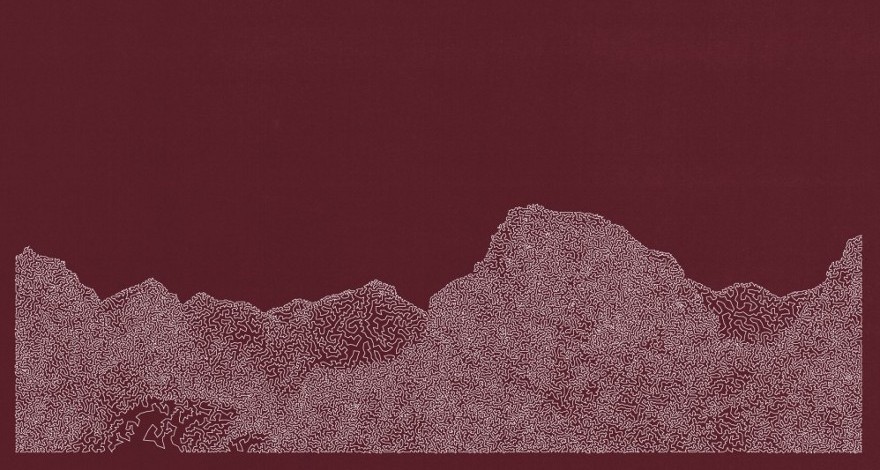

This image suggests, arguably, that more than any concept of ‘home’ it is actually time that lies at the heart of the book – specifically, an uneasy oscillation between the past and a series of possible futures. One of the key questions to be addressed in any attempt to move beyond civilisation is whether one is moving forward (bravely forth into the future) or backwards into some mythologised past. It’s a question that crops up again and again. “Romanticising the past is a familiar accusation,” writes Paul Kingsnorth in his brilliant analysis of the writings of Theodore Kaczynski (aka the Unabomber) “made mostly by people who think it is more grown-up to romanticise the future.” A little later though, he admits, “I know there is no going back to anything.”

Importantly, this is not simply a theoretical argument: it’s a debate that has divided the green movement cleanly in two. On the one hand are what Doug Tomkins, founder of The North Face and Esprit, calls “the tech-optimists” – those who believe, in the words of the Dark Mountian manifesto, that “the converging crises of our times can be reduced to a set of ‘problems’ in need of technological or political ‘solutions’”. And, on the other, those who see wholesale systems collapse as a necessary step on the path of change. Tomkins, who, along with his wife Kris, abandoned his career in business and dedicated his life to buying up and protecting wild land across Latin America, describes wind turbines, for example, as “the icon of techno-industrial culture”. He goes on to observe: “The way of thinking that would create those windmills is the way of thinking that caused climate change in the first place.”

The Dark Mountain solution is ecocentrism. But it’s a tricky one, as Kingsnorth acknowledges: “[It] seems to me to be something that is both completely necessary and, at least at this moment in time, almost completely impossible.” This idea of the necessary impossibility – so closely associated with the writings of Jacques Derrida – offers us a key insight. How to foster “the idea of intrinsic value to the rest of the world”? How to place nature at the centre of human thinking, without doing so for human-centric reasons (nature as a resource to be consumed; saving the world as equal to saving humanity etc)?

Matt Szabo suggests “thinking like a peasant” whilst Kingsnorth posits pantheism and gets out his scythe. Meanwhile, one solution not touched upon here might be found in the writings of Rupert Sheldrake, Graham Nicholls and others. By very different paths (epigenetics on the one hand; out-of-body experiences on the other) both have come to the tentative suggestion that consciousness may be something bigger than the individual, a phenomenon that binds together all humanity and indeed all life. If this is true, it offers a way of thinking that moves beyond the opposition of human/nature and begins to see the one as a component part of the other.

And even if it isn’t, there are many routes up a mountain, especially as the light begins to fade. Dark Mountain is a radical project, and a brilliant one, capable of opening your eyes in the encircling twilight. The journey onwards begins here, with this step back.

dark-mountain.net

Comments

It would be interesting to

It would be interesting to delve deeper and start discussing some of the concepts raised, particularly those of Doug Tompkins and of the valuing and protecting of nature in a non human-centric way.

Add new comment