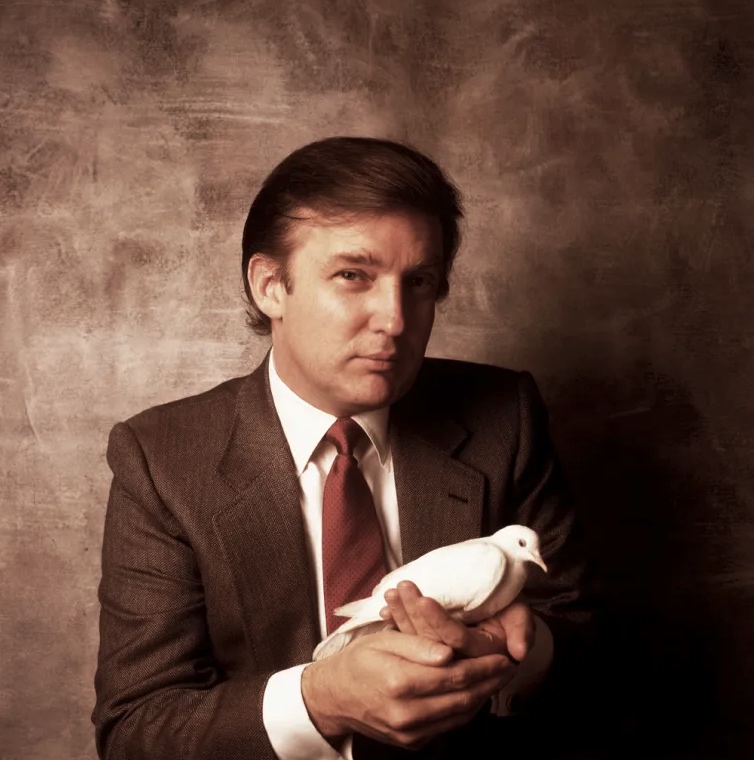

Man in suit and tie cradling a dove. Inset from a portrait by William Coupon.

A NOTE ABOUT THE FOLLOWING ESSAY FROM THE AUTHOR

Although this essay was originally written in the early months of the presidency of Donald Trump in 2017, most if not all of the red flags were already raised, warning of the danger this spiritually impoverished man posed to the United States and to the world. Luckily, the late Robert L. Moore was up to the task of describing and diagnosing that pathology we recognized then and, dismayingly, still see now playing out on the embattled landscape of the American psyche.

Rereading my essay seven years on, I see little I would change. I might quibble, though, with my assertion that Trump is nothing new in American politics. The Trumpian “rough beast,” I now believe, is a different breed of animal than even our worst past presidents. The fact that his continually shocking breaches of dignity, decency, and honor have become routine entertainment for his admirers reflect abysmally on those who support him, especially his cynical funders. As for the rest, the great majority of Trump supporters, I tend to view them as victims of widespread economic inequality, lack of education, literalist religion, and the erosion of consensual reality precipitated by digital media — a perfect storm that has dispatched many down the chute to Trump’s hell of resentment and rage.

No matter who wins the coming election, work will need to be done to, as Stevie Wonder has formulated in a recent song, “fix our nation’s broken heart.” Whether it can be done or not, in good faith we must try.

There’s no doubt that Trump — as Moore says of those who oscillate “between arrogance and a terrible self-hate” — appears well on the way to personal psychic disintegration. I stand by my assessment that in the end, Trump’s story will be seen as tragedy. The only question is how many others among the electorate and his handlers will allow him to take them with him. In this and other matters, Moore’s book remains an essential guide.

— Thomas R. Smith, October 26, 2024

"If you would understand the deeper roots of terrorism, greed, and religious fanaticism, read Facing the Dragon. But be forewarned: you may find some offshoots in your own garden." — Jean Singer, author of Boundaries of the Soul.

In the summer of 2017, following the shocking suicide/murder of Robert L. Moore and his wife, Margaret Shanahan, I realized with a sense of muted regret that, more than a dozen years after its publication, I still hadn't gotten around to reading Robert's final completed book, Facing the Dragon: Confronting Personal and Spiritual Grandiosity. I knew that Robert Bly, with whom I'd been in close contact at the time of the book's appearance, had words of high praise for Facing the Dragon. He said in his blurb: "The question is what to do with the God energy [in us] in a time of secularism. Moore gives frightening answers to questions people haven't even begun to ask." And since, in the summer of 2016, possibly the most grandiose presidential candidate in American history had just ascended to his party's candidacy, it seemed an appropriate moment to go back and hear what Moore was saying on that subject in the comparatively "normal" early days of Bush II and the second Gulf War.

Reading Facing the Dragon in 2017 has left me convinced that Robert Moore's examination of grandiosity and the dangerous narcissism that can come with it is a more useful key to understanding the convulsions our democracy is now undergoing than more mainstream psychological analyses, which tend to neglect the spiritual dimension of our crisis.

Moore's subject in Facing the Dragon is the grandiosity that follows us into adulthood from our authentic experience of the sacred in childhood. Moore was a Jungian, able to see the dark or shadow side of our luminous apprehensions of the divine. When one identifies personally with the divine, of which we all carry a small spark – and which Moore liked to call the Great Self Within – we enter the territory of pathological narcissism, as opposed to a healthy narcissism which enables "self-esteem and a healthy exhibitionism." (Facing the Dragon, p. 100. Further page references: number only) In contrast, pathological narcissism, Moore points out, oscillates "between arrogance and a terrible self-hate."

Facing the Dragon is essentially a tool for dealing effectively with the grandiosity that can too easily lead us down a path of personal psychic disintegration while in the process doing great harm to others around us, and even to the structures of democratic government built up by the labor and sacrifices of past generations.

Illustration courtesy of Mark Gardiner.

As a Jungian, Moore was unafraid to take on the subject of evil, which the more superficial manifestations of New Age philosophy have specialized in avoiding. In keeping with many religious and indigenous conceptualizations of evil, Moore believes that evil has an agency of its own. In mythology the vampire that "thrives on the absence of light" is an apt personification of evil: "It manifests great intelligence, as if it has lived many lifetimes and has methodically developed a capacity to detect and exploit personal weaknesses and blind spots. It preys in a seductive way on your rightful need for attention and recognition that is not in itself demonic." (6) Early in Facing the Dragon, Moore lists ten assumptions about the nature of evil distilled from ancient wisdom traditions. We might especially apply #3 on that list to our political sphere: "The chief tactic of evil is to present the human individual and community with a false, deceptive representation of reality. In short, it lies." (5)

At least as urgent for our present society is item #9 on Moore's list: "Evil denies the reality of death and all human limitations." (6) Limitation is a word that comes up frequently in Facing the Dragon, most centrally in Moore's discussion of humility as an antidote to the more reckless, destructive kinds of unconscious grandiosity. True humility," Moore says, consists of two things: "(a) knowing your limitations and (b) getting the help you need." (72) As he points out, this is the foundation of twelve-step groups' success in countering addiction.

Identifying evil helps us to identify what Moore calls the "anti-life" forces operating in our world. Evil is anti-life, and "tries to destroy relatedness" through "deceit, lying, and illusion." (37) Evil hates community and the power that individuals gain by banding together for the common good; therefore evil "wants to get you alone and isolate you." In the post 9/11 world, we recognize evil's great recent penchant for manipulating us through fear and distrust; people who no longer know who or what to believe are especially susceptible to becoming isolated in the darkness of lies chiefly designed to disempower them.

Moore's wide-ranging book explores these themes from multiple perspectives, with especially insightful chapters on "The Archetype of Spiritual Warfare," '"How Modern Spiritual Narcissism Leads to Destructive Tribalism," and "The Psychological Sources of Religious Conflict." These broodings all point toward a recognition that the spark of divinity we all carry inside, like a particle of spiritual radium, is real, powerful, and deadly if mishandled. Moore reminds us that "narcissistic pathology" is "like sin, a condition common to all. . . . psychologically speaking, you shouldn't ask, 'Am I carrying any narcissistic pathology?' You should ask, 'Where is my narcissistic pathology? How am I acting it out?'" (147)

§

I'd be very surprised if by now the name Trump, Trump, Trump isn't thumping around in the reader's mind like the sound of a flat tire flopping along on a severely potholed street. There is something uncannily prescient in Moore's anatomy of pathological grandiosity, as though he could see our present catastrophe materializing in the distance. It would be a mistake to think that Trump and his regime of fear and self-serving greed are something new; we have been here before (think Robber Barons, think Nixon), our "rough beast" slouching back around, as Robert Bly, among others, has warned us repeatedly that it would. In a 1990 essay, "Form in Society and in the Poem," Bly observed:

"Something in us wants and wants endlessly. Witches and giants in fairy stories stand for that wanting. The witch wants a ton of wheat sorted in an hour, she wants all the fish in the river to be laid out by species and in neat rows this afternoon; the giant wants to eat now, now, now, and he can eat for days, he can eat all the food produced in the county this year. Goya's painting of Saturn eating his son suggests the anguish inseparable from that endless, repetitive, abusing hunger.

Kohut and the self psychologists have named the source of this infinite hunger infantile grandiosity or psychological omnipotence. When a two- or three-year-old child is on the grandiose road, it has godlike goals and is not at all sure that it is not God. Limits, conditions, bounds, confines are something the child doesn't want to hear of. . . ."

William Blake. 'The Good and Evil Angels.' 1795–?c.1805. Tate Britain. [o]

It's hard to believe that these words weren't written during our ongoing national train wreck under a president who seems to eerily embody these witch and giant energies.

It seems likely somewhere in the inscrutable murk of Trump's psyche he is experiencing that anguish Bly identifies in Goya's painting. Trump's insatiable appetite for recognition is on a collision course with his evident psychological and emotional lack of fitness for the job he has taken on. It's clear that Trump didn't bargain for the extreme challenges of the office. "Underestimating what you are dealing with is one of the marks of grandiosity and immaturity," Moore says (34) When in his campaign, claiming to address America's problems, Trump said, "I alone can fix it," red flags signaling grandiosity bordering on megalomania shot up instantly to tell us that this was not a man grounded in a realistic sense of self. He'll build a wall, deport undocumented aliens, keep out all Muslims, give everyone health insurance without raising taxes, bring back the coal industry, everything will be wonderful. Trump has already left behind him a trail of extreme claims incalculably damaging to truth. In fact, having risen to the presidency is no doubt making the problem worse. Moore says, "It overstimulates our grandiose energies when we start looking at the large problems facing humanity. We become very anxious. It's like having a 300-pound St. Bernard jumping around in your head." (47)

Moore points out that "Cultures around the world taught that the great engine of evil was arrogance, or hubris, as the Greeks called it." (12) Trump's arrogance or hubris is psychologically isolating, and one must posit an intense insecurity underlying his notoriously reactive twitters, many of which express a sense of impotence strangely at odds with the magnitude of his office. Moore pinpoints "sensitivity to criticism" as one of the earmarks of the narcissistic personality disorder:

"If you are a narcissist and people criticize you, you may experience great anxiety and fragmentation. When they are not criticizing you, and especially if they are constantly mirroring you, you may feel pretty calm with little fragmentation anxiety. . . . Your anxiety level will stay fairly low only as long as you can arrange for everyone to adore you, because that serves as a camouflage and no one can detect how easily you become anxious and subject to fits of rage." (pp. 111-12)

Trump appears to operate outside the boundaries of ordinary friendship in which one opens up on a deeper emotional level. If his ghostwriter, Tony Schwartz (The Art of the Deal), is to be believed, Trump views even personal transactions as a competition in which someone must win and the other lose: "Trump felt compelled to go to war with the world. It was a binary, zero-sum choice for him: You either dominated or you submitted. You either created and exploited fear or you succumbed to it. . . ." Echoing Jung, Moore observes that "Without authentic and grounded relationships, we can easily get a little bit crazy, because you have no one to challenge your inflation." (133) Insider reports paint the Trump White House environment as one of fear and distrust rather than of cooperation and common purpose; Trump seems to share the right wing preference for family over polis. Even so, Trump's relationships with his family are very difficult for outsiders to "read." If we can empathetically put ourselves in Trump's shoes, we may find ourselves in a profoundly lonely place. It seems a fair bet that his story will finally be seen as an American tragedy. Whether we as a society will ultimately profit in wisdom from the debacle is anyone's guess.

§

The "anti-life ego" of the pathologically grandiose narcissist is self-destructive. "Part of a person's psyche is hell-bent on destroying her and not allowing her to have any love, not allowing her to have any trust, not allowing her to have any successful transformation of her patterns of relatedness and her patterns of human interaction." (40) This may illuminate a basic disconnect between Trump's narcissistic demand to be universally loved and the extreme administration he has put in place to carry out policies deeply repugnant to the American people and to the rest of the world. A leader who truly desires to be loved by the people promotes a spirit of compromise and reconciliation. But Trump as President has persisted in dividing rather than uniting. This basic incoherence has already led to Trump's becoming one of the lowest-polling presidents in American history and the object of derision world-wide. And this in turn drives his narcissistic ego into new frenzies.

And of course "anti-life" is also harmful to others, whether it manifests in outright hostility or in a programmatic neglect of the social and environmental conditions that sustain healthy life for the individual and the collective. Robert Bly has often remarked on the "death energy" of our society, and surely our tolerance of openly destructive figures such as Trump and appointees such as Scott Pruitt, Jeff Sessions, and Steve Bannon (a kind of Mount Rushmore of Hell) speaks poorly of our collective values, such as they may be. What has changed to bring us to this precipice? Moore remarks that up until the early 1950s, Americans could feel, rightly or wrongly, that we had fought "moral" wars. Our moral world or "sacred canopy" was still somewhat intact. "After Korea," Moore says, "it was collapsing, and by the time Vietnam arrived, we no longer had a functional sacred canopy. In the process of modernization, the sacred canopy of myth has collapsed, and that means we have nothing to return home to." (57) This has left our society vulnerable to "the fantasy of expecting progress without spirituality." (63)

Portrait of Donald Trump by William Coupon for Manhattan, Inc., 1983. [o]

I know that in focusing on the relevance of Moore's book to our present spiritual-political dilemma, I have given the reader more "dragon" than "facing." My emphasis here on the negative somewhat reflects Moore's. I wouldn't want to give the impression, though, that Moore's outlook is gloomy or hopeless. While he refuses to sidestep the issue of what he calls "radical evil" — the evil that is rooted alongside the good in the human psyche — he suggests various resources for "facing the dragon," which include religious community, active imagination, prayer, and mythological work. Of the latter he says, ". . . we all need to sit around the global campfire once again and tell stories to each other, tell people what is happening. With people sitting around the campfire, and the fire burning away, we can say, "Okay, what have you heard about what is happening over in the homeland?" So the ritual elders, the people who perhaps are better storytellers than the others, will say, 'I understand that such and such is happening in the homeland.' . . . If we will do [this] . . . our species might begin to wake from its long sleep and repetitive nightmares." (197-98)

Moore's chapter on "Dragon Laws" identifies areas in both private and public life where we can be alert to the destructive potential of pathological grandiosity to cause damage and harm. One item from the second category should cause us to weigh carefully how we respond to our politicians' present abuses: "Grandiose, disrespectful, and unempathetic behavior by people with social and political power always generates powerful, rage-filled compensatory outbreaks of madness." (210) Overly reactive responses, lacking self-reflection, can often set back worthy causes. Moore makes a further, more hopeful generalization: "When a tribe's spiritual grandiosity declines, it immediately gains more radiance as a portal for the incarnation in history of what Tillich called the 'authentic spiritual community.'" (216)

Moore especially advises going beyond the myths of our own "tribe" to open ourselves to what he beautifully calls "the entire human symbolic trust" of mythology. Yet he cautions against the simple-minded goal of finding a new myth to replace an outworn older one: "When people think they can solve the world's problems with a different myth, they are only offering to make you one-sided in a new way. The issue is to realize that we need to create a container, a chalice or grail, that holds with reverence the entire human symbolic trust and enables us to cherish it all." (139)

In our world of fear and division, it becomes even more important to make that effort to "create a container," in ourselves, in our communities, and in our nations, to "hold with reverence the entire human symbolic trust," a wealth that, as Jung argued, belongs to every person without exception. "Our war," says Moore, is not with each other but with "the pathological infantile grandiosity that seeks to destroy the human species." (134) Certainly with the past election we have seen the shocking escalation of that warfare. As we spin into our "rage-filled compensatory outbreaks of madness," we might heed Moore's reply to a famous revelation by the Walt Kelly comic strip character Pogo, "We have met the enemy, and he is us.":

". . . psychoanalysis makes it possible for us to refine that. I would like to sit down and talk with Pogo about this. I would like to say, 'Pogo, I don't think our true human selves are the enemy. Our grounded and human creaturely egos are not the enemy. The enemy is that unconscious grandiosity within us that constantly tries to persuade us to forget our limits and forget that we need help, to forget that we need others, or as the Native Americans are able to say, to forget that we are all related and all of one family.' " (134)

William Blake.’ The schismatics and sowers of discord.’ 1824-1827. 373 mm (14.68 in); width: 527 mm (20.74 in). National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

I could go on and on about this deeply relevant and healing book and its author, but I've said enough. My approach here has been more suggestive than descriptive, an attempt to capture a few of the connections that fired for me while contemplating Facing the Dragon in the light of events a decade and a half after its publication. Personally, I'm undecided about Moore's belief in the nature of evil, but I do agree with him that "the demonic is closer than you think." (1) What the demonic is is another question. Moore's fellow Jungian, Marie-Louise von Franz, memorably defined the demonic as siding with gigantic impersonal forces against common human concerns like wanting enough to eat and a place to live. By this token, the statements "a plague would be good because it would thin the herd" and "a war would give the economy a boost" are demonic. A good guide for individuals and for nations, I think.

In closing, we were lucky to have Robert Moore with us for as long as we did, and as we approach the first anniversary of his death, the occasion of this appreciation, let's send out another prayer for his spirit and for his wife Margaret's. Meanwhile we remain humble in our ignorance of the torments that must have driven them to their final extremity, an ending that in no way diminishes the importance of their lives' accomplishment. Any book of Robert's will richly reward the time and attention we give to it, but for reasons I hope I've made clear in this essay, it was his last, Facing the Dragon, that best equips us to understand and address the challenges of the grandiosity-driven chaos of our present spiritual-political moment. It's the next best thing to having Robert Moore here with us now. ō

NOTES ON SOURCES

This essay was originally published under the title, "Trump and the 'Anti-Life Ego': Reading Robert Moore's Facing the Dragon in 2017' for the "Real Words: Real Men" blog on the Minnesota Men's Conference website. Robert Bly's essay "Form in Society and in the Poem" appears in his book, American Poetry: Wildness and Domesticity, Harper & Row, New York, 1990. Tony Schwartz's writings on Donald Trump have appeared in The New Yorker, The Washington Post, and other publications. The piece I quote here was reprinted in the Minneapolis Star Tribune on Sunday, May 21, 2017. I would also refer the reader to Alex Morris's thorough psychological analysis, "Trump and the Pathology of Narcissism," in the April 20, 2017 issue of Rolling Stone, which examines Trump with reference to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Special thanks to Mark Gardiner, editor for the first appearance of this essay.

THOMAS R. SMITH is a poet, essayist, editor and teacher. He worked as Robert Bly's personal assistant for over 30 years and has edited four books on Bly, most recently the forthcoming The Garden Entrusted to Me: Essays on Poetry and the Writing Life. His recent books include Medicine Year and Poetry on the Side of Nature: Writing the Nature Poem as an Act of Survival. Thomas lives in western Wisconsin. View Thomas' website here.

Add new comment