Tom Jeffreys will be discussing the contents of this article and giving the lowdown on the most intriguing contemporary artists working with and in nature today on 9th August, as part of this year's Wilderness Festival.

It’s impossible to draw very definite conclusions from something as large, sprawling and diverse as the Venice Biennale – a six month-long extravaganza that sees historic sites such as the Arsenale, Giardini and sundry grand palazzos across the slowly sinking city play host to contemporary art from across the globe. Or, rather, perhaps it’s too easy: with so much work on show, there will almost always be something that fits into the pre-existing interests of the critic in question. Certainly this year, as somebody interested in humanity’s relationship with the natural world, and how that might be rethought, there is much to comment on.

But before we get there, it’s arguably just as impossible to take seriously any professed attempts to question our treatment of the natural world, without overlooking the fact that the Biennale itself sees so many critics, curators, artists, decision-making administrators, collectors, celebrity-spotters and hordes of art-loving tourists flying into the city’s two airports, arriving by yacht or by vast cruising ship. Works of art are packed and shipped and unpacked. Millions of flyers and books and press releases are printed out, put into tote bags, taken home and binned. It’s impossible to overlook the waste that art generates, but everybody does…

It’s impossible to overlook the waste that art generates, but everybody does…

Each instalment of the Biennale centres on a theme, which this year, for the 55th, is Il Palazzo Enciclopedico, or The Encyclopaedic Palace. Chosen by the 2013 curator – Massimiliano Gioni, the youngest ever – the concept stems from a 1955 application to the US patent office by Italian self-taught artist Marino Auriti, in which he proposed to construct a vast tower that could function as the repository for the entirety of human knowledge. The central exhibition – split across two vast gallery spaces in the Arsenale and Giardini – is therefore concerned with ideas around knowledge – its construction and storage – as well as anthropology, systems of classification, and the increasingly fashionable concept of outsider art.

That means that, for an event that is supposedly a championing of contemporary art, at its heart is surprisingly little contemporary art. Instead there are all manner of historical artefacts, museum objects and the strange scribblings of nineteenth century ‘visionaries’, South-East Asian shamans, or early twentieth century self-taught artists, or ‘artists’. Much of what contemporary work there is plays on a similar aesthetic – Ed Atkins’ video portrait of the personal collection of Andre Breton, for example, or Danh Vo’s transposed temple. All art here, it might be said, aspires to the condition of the artefact.

Steady streams of water drip down from clouds above, and run off into puddles below.

Outside of this sprawling double centre, the Biennale is largely made up of national pavilions, in which various committees from countries around the globe decide who ought to represent them on the world stage. Artists here are free to respond to the centralised theme or not, as they see fit, and this year a surprising number have – notably Khaled Zaki’s Sphynx-esque pieces in the dimly lit Egypt Pavilion, the work of Petra Feriancova and Zbynek Baladran for the Czech Pavilion, and Whitney McVeigh’s installation of cluttered academia in the Gervasuti Foundation [pictured above], one of many collateral events that spring up across the city around Biennale time. The Estonian pavilion, meanwhile, consists of a scrupulously careful archiving system that would have been right at home in 2011.

Whether or not it’s a result of Gioni’s overarching theme, or symptomatic of a more broadly shifting attitude, or simply a reflection of the critic’s ability to find what he’s looking for, man’s relationship with nature seems to be a prominent source of interest this year. Inside the Encyclopaedic Palace, for example, are works such as Kan Xuan’s Millet Mound – a double-banked display of some 70 screens intertwining Chinese landscape, agriculture and political history. Meanwhile, artist-hermit Patrick Van Caeckenbergh’s strange trees (half-housing; half-alive) [pictured above] bring a troubling sense of faded mythology. And Lin Xue extends such mythology forwards into the future, with amorphous fantastical landscapes, painstakingly drawn with sharpened bamboo dipped in ink. Steady streams of water drip down from clouds above, and run off into puddles below; somehow rooting these tiny floating worlds – shifting quilts of texture and form – amid the otherwise empty blank expanse of clean white paper.

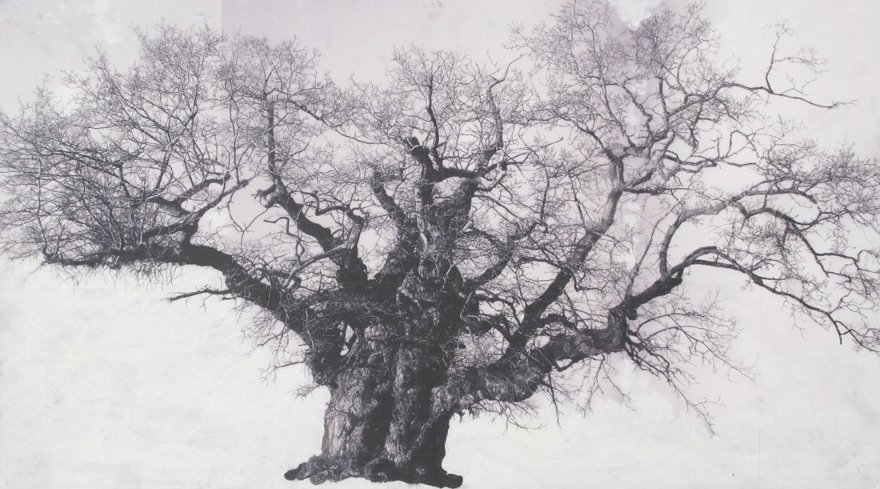

This sense of rooted inter-relationship is literalised in both the Kosovo and Belgium Pavilions. For the former, Petrit Halilaj presents a mud-constructed covered walkway, through which the visitor must tread gingerly in semi-darkness. Portholes provide a view of featureless gallery white, overhung by a canopy of twigs and, bizarrely, coathangers. In the latter, JM Coetzee curates the work of Berlinde De Bruckere [pictured top]; his introductory text setting the tone for a fantastical intertwining of something resembling mankind with a crippled kind of nature. The work – a colossal sculpture of a fallen tree, its branches intertwined to form a single trunk-limb, patched up and bandaged, pollarded and felled – is especially powerful under a grey, gauzy, slowly waxing gloom. But as ever with fantasy, it’s a fine line away from ridicule, over which this arguably teeters.

Laitinen chopped down a large square of Finnish forest and rebuilt it arranged by colour.

Similarly ‘rooted’ is Antti Laitinen’s work for the Finland Pavilion [pictured above]. On show is documentation of an old work, The Island, for which the artist constructed an island in the Baltic Sea, one sandbag at a time, as well as the more recent Forest Square series. This involved Laitinen chopping down a 10x10 metre square section of Finnish forest, sorting all the different materials – soil, moss, wood etc – and rebuilding the forest arranged by colour. Outside the pavilion when we visit, he’s busy nailing trees (back) together.

Environmental issues are just as prominent in the Bahamas Pavilion, which sees Tavares Strachan present large images of hummingbirds created out of collages of other endangered species, as well as two lightboxes each containing a block of ice. One is taken from the North Pole and set to -79°C, the other a clone, and set at -86°C. Ice is also present in the form of a melting monolith outside on Riva Ca de Dio, the work of Stefano Cagol for the Maldives Pavilion, which is generally a little simplistic in its foregrounding of tension between residents, tourists, business and conservation.

More complex in terms of exploring relationships with nature is Simryn Gill’s work in the Australian Pavilion, including photography, a mini-library, and a large-scale collage of ink and tiny scraps of paper on wooden panels, that hints at swarm behaviour and the troubling way in which language can both open up a relationship with the natural world, and close it down. This might be compared with Aurelien Froment’s video piece, Pulmo Marina, [pictured above] on show at the Palazzo Contarini Polignac as part of the Victor Pinchuk-funded Future Generation Art Prize. Here, a simple, beautiful video of a jellyfish is presented with a blandly folksy US voiceover that explores our changing conceptions of these strange animals. Historical, mythical, and contemporary scientific understandings of jellyfish are all introduced, before the defining moment – a perfectly judged self-reflexive turn which suddenly jolts you into an awareness that this has not been filmed deep in some fathomless ocean inaccessible to humans, but in a carefully spot-lit tank in an aquarium in Monterey Bay. Jellyfish can’t be tagged (or they’d sink) and can therefore only be observed and studied in artificial environments such as this one. “Jellyfish just don’t fit the categories,” we’re told.

This idea of categorisation and its overrunning is to the fore in IF A DandeLION COULD TALK, an exhibition curated by Adina Drinceanu. The show focuses on a group of 1970s Italian artists who worked together under the collective name Sigma 1 and demonstrates their exploration of order and coding in the natural world – whether or not, say, geometry is somehow ingrained in nature or imposed by humanity upon it. One of the group, Ștefan Bertalan, also has a symbolically gridded structure on show in The Encyclopedic Palace, where such gridding systems are echoed by the graph paper drawings of KP Brehmer.

Something similar is at work, I think, in Thierry De Cordier’s 2012 sea paintings [pictured above] – darkly violent and uncontrollable – overlaid in gold writing or overlaying and half-concealed: delicately printed or handwritten text naming and taking control or pinning down in place and time: Tempete en Mer du Nord – Etude No3, for example, or NOORDZEE No2, 2. By contrast, a trio of Chinese painters in Culture World Becoming and Confronting Anitya – Zhang Fan, Mao Lizi and Guan Jingjing – each employ varying degrees of abstraction to demonstrate something untenable, unnameable, ever out of reach.

Perhaps it simply suggests that humanity’s relationship with the world is always a cause for discussion.

More different still – incomparable really – is Richard Mosse’s work for the Ireland Pavilion. Across both photography and a disorientating video installation, he uses now defunct military-grade infrared film to document years of violence in the Eastern Congo. The resulting work is dizzyingly beautiful and harrowingly direct, and at the same time. Like all great art, it prompts many thoughts, suggests many purposes, but, in the context of thinking about the environment, it makes us look again at landscape – suddenly, now, a place of both otherworldly beauty and hidden terror. Always able to be rethought anew.

But perhaps none of this is new after all, even newness itself. One of most obviously environmental exhibitions is in the Nordic Pavilion, for which Terike Haapoja combines trees and technology to explore ideas around death, decay and communication. How might nature speak for itself, she wonders. But in a sense she has no choice: the Nordic Pavilion, designed by Sverre Fehn and built in 1962, was constructed around three plane trees that the city of Venice wanted to preserve. Nature is therefore an unavoidable intrusion. So too is history. Whether this might be seen to represent some kind of humility on behalf of the architect in the face of nature’s authority or, on the contrary, a hubristic taking control, and boxing off of nature’s power: that is something continually open to questioning. Perhaps it simply suggests that humanity’s relationship with the world in which we exist is always a cause for discussion – for hope as much as for concern.

The 55th Venice Biennale continues across Venice until 24th November 2013.

http://www.labiennale.org

Comments

As we see from Tom Jeffrey's

As we see from Tom Jeffrey's insightful overview of the Venice Biennale, the technological assault on the regenerative forces of nature, of Mother Earth, provide vital subject matter for our most visionary artists. This artistic, journalistic, academic and cultural commentary needs to extend to close consideration of the toxification of the mental environment especially through Black Pyschological Operations such as those now proliferating under the cover of the fraudulent Global War on Terror. Mainstream media are being paid to transform minds into garbage dumps of conspicuous consumption. Whole population groups, but especially Arabs and Muslims, are demonized to be rendered as viable targets in the ultimate scam of neverending warfare.

Add new comment