ANTICIPATORY HISTORIES | Edited by Caitlin DeSilvey, Simon Naylor & Colin Sackett | 80pp, sewn paperback with flaps, £9.00. Uniformbooks.

In recent years reports of accelerating sea level rise, species extinction, shifting weather patterns, and stressed landscapes have become increasingly common. Although we are well supplied with scientific information about environmental change, we often do not have the cultural resources to respond thoughtfully and to imagine our own futures in a tangibly altered world.

This book poses the term ‘anticipatory history’ as a tool to help us connect past, present and future environmental change. Through discussion of a series of topics, a range of leading academics, authors and practitioners [see list of contributors below] consider how the stories we tell about ecological and landscape histories can help shape our perceptions of plausible environmental futures.

Work on the project, Anticipatory histories of landscape and wildlife (which resulted in this book), was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council Landscape and Environment programme in the UK.

The principal network output is a glossary of terms that relate in some way to anticipatory history, produced in collaboration with Uniformbooks. All of the core network participants—from artists to scientists—were invited to suggest terms that should be included and then asked them to take ownership of those terms and to produce entries for them:

Acclimatisation, Adaptation, Art, Aspic, Besanded, Birds, Catastrophe, Coastal squeeze, Collection, Commons, Continuities, Cycle of erosion, Discontinuity, Dream-map, Ebb and flood, Enclosure, Entropy, Epiphany, Equilibrium, Erosion, Extinction, Futurology, Introductions, Liminal zone, Living landscapes, Longue durée, Managed realignment, Memory, Monitoring, Moor, Museum, Natural history, Natural selection, Nature writing, Palliative curation, Place, Presentism, Record, Recording, Rewilding, Rhododendron, Sculpture trail, Shifting baseline syndrome, Story-radar, Temprocentrism, Tides, Uncertainty, Unfarming, Woods, Zone of exclusion.

The idea has not been to communicate scientific or policy ideas, but to produce entries that provoke readers to problematize, or reflect critically, on received ways of thinking about environmental change and its pasts and futures.

Despite being a collection of contributions by many hands, this unusual book is not only elegantly designed but uniformly erudite and well-written. It is a form of gazetteer owing something to Raymond Williams’ pioneering work Keywords, which made it clear how much of our thinking is both illuminated or occluded by the manifold meanings of some of the complex words used in political and cultural discourse. Anticipatory Histories also builds on that fine 2004 collection, Patterned Ground: Entanglements of Nature and Culture, and to a lesser degree, Common Ground’s enchanting 2006 compendium, England in Particular.

In brief, various authors have been given free rein to elaborate upon a number of critical terms now at work in debates about landscape, ecology, climate change and futurology, ranging from the technical to the poetical, and from the instrumental to the epiphanic. Thus we get wonderful expositions on what is meant by Adaptation, Dream-maps, Entropy, Liminality, Memory, Rewilding, and Presentism, amongst many others — in fact fifty glossaries in all.

The initial brief for this research endeavour was “to explore the roles that history and story-telling play in helping us to apprehend and respond to changing landscapes, and to changes to the wildlife and plant populations they support.” The editors rightly caution themselves and their readers against the dangers of instrumentalising the history-writing process: bending a reading of the past to suit the needs of the present and the future.

What was once called the search for authenticity in human existential terms now applies to concrete and clay.

Not surprisingly forms of land ownership and its management and stewardship loom large. The short essay on ‘Commons’ rehearses Garrett Hardin’s famous essay on ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, which suggested that self-interest will always ultimately defeat the social aims of things held in common. However, the Commons essay does not reprise historian E. P. Thompson’s counter-argument that in particular societies at particular times, a ‘moral economy’ is brought in to play to regulate private behaviour. It was also surprising—though perhaps there wasn’t enough room—that the entry on ‘Rewilding’ focused entirely on vegetative succession with no mention of the fearful ‘Beast of Bodmin Moor’, nor of the proposal to re-introduce sea-eagles to the East Anglian shoreline.

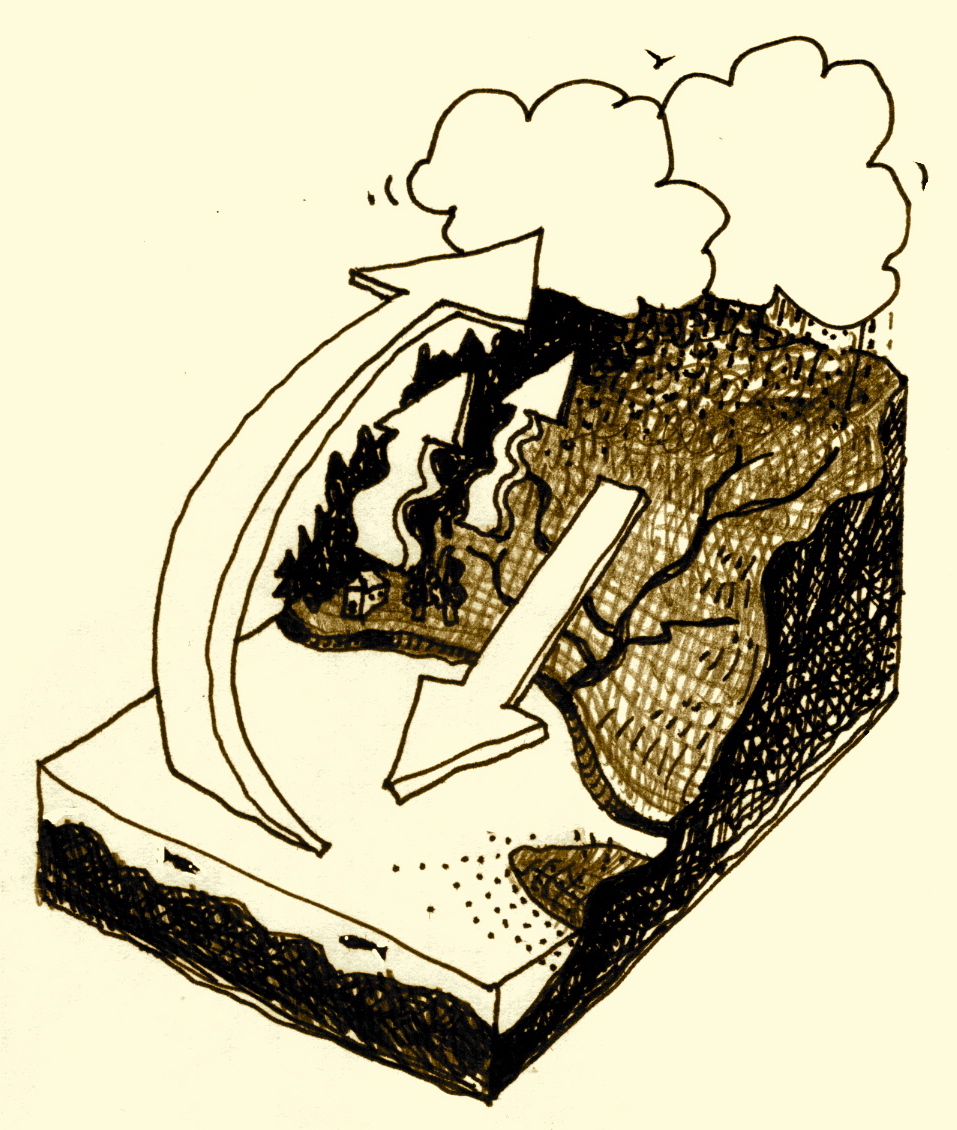

Drawing by Brad Harley.

Attention also gravitates towards the newer, more problematic landscapes which now require a fuller understanding of how they might be managed in the future: the ‘edgelands’ or ‘drossscapes’ produced by failed urbanisation or de-industrialisation. Are these settings just as valuable and worth conserving as farmed or so-called natural habitat? What was once called the search for authenticity in human existential terms now applies to concrete and clay. Here the newer discourses of psycho-geography and psycho-biogeography are proving to be invaluable in summoning meaning and history from even the bleakest terrain (on such matters see the excellent entry, ‘Liminal zone’).

I had not heard of Rephotography before, nor ‘Shifting baseline syndrome,’ let alone ‘Palliative curation’.

There are no settled positions on any of these matters any more, as the entry on ‘Enclosure’ concludes. Once upon a time open common land was hedged in and parcelled up into private lots, which had very bad social consequences. When, a century or so later, the hedgerows were uprooted in the name of industrialised farming, much of the flora and fauna using them as habitat disappeared. Now we are re-instating hedges again. “Perhaps,” the author of this entry concludes, “we might think of enclosure as an example of the human modification of land that slips from its moorings, and accept that each generation makes the enclosure it needs.”

The book contains words, terms and concepts that are completely new to me, including the book’s suggestive title, ‘Anticipatory History’. I had not heard of Rephotography before, nor ‘Shifting baseline syndrome’ let alone ‘Palliative curation’. ‘Presentism’ I knew, but not how to pronounce it—and still don’t. Yet these elucidations are vital resources in the debates ahead about how we handle the transition from the past into the future, and provide a much-needed contribution to the crucial matter of ‘Inter-generational equity’.

A terrific and thought-provoking book.

~

[Anticipatory History features contributions by Tim Birkhead, David Bullock, Chris Caseldine, Stephen Daniels, Tim Dee, Caitlin DeSilvey, Phil Dyke, Tom Freshwater, Toby Goaman-Dodson, Gareth Hoskins, Alex Hunt, Hayden Lorimer, David Matless, Simon Naylor, Shaun Pimlott, Colin Sackett, Lucy Veale, Justin Whitehouse, Victoria Whitehouse.]

KEN WORPOLE is a writer and social historian. His books include Here Comes the Sun: architecture and public space in 20th century European culture (2001), Last Landscapes: the architecture of the cemetery in the West (2003) Modern Hospice Design: the architecture of palliative care (2009) & Contemporary Library Architecture (2013). Ken has also collaborated with photographer Jason Orton on two books exploring the coastal and riparian landscapes of the Thames Estuary and East Anglia: 350 Miles (2005) & The New English Landscape (2013).

He blogs at thenewenglishlandscape.wordpress.com/

A long excerpt from the book will appear this Tuesday, May 27.

Add new comment