A herd of New Forest ponies grazing peacefully at New Forest Northern Commons, Hampshire | © National Trust Images/John Miller.

Think Like A Commoner: A Short Introduction to the Life of the Commons (Second Edition)

By David Bollier

New Society Publishers

7 SHORT EXCERPTS FROM THE BOOK

When my seat mate on the airplane turned to me and abruptly asked, “So what do you do?” I replied that I study the commons and work as an activist to try to protect it.

Polite bewilderment. “Say what?” It was not the first time.

So I cited the familiar references — the Boston Common and medieval pastures — and moved on to the so- called tragedy of the commons, the meme that brainwashed a generation of undergraduates.

Sensing a quiver of interest, I ventured further, mentioning open-source software, Wikipedia, countless collaborative websites, and billions of books, articles, images, and music made shareable via Creative Commons licenses… community supported agriculture and community land trusts. The “gift economies” of blood donation systems, mutual aid networks, and Indigenous commitment-pooling traditions. There are fisheries managed by coastal fishers, water protectors defending precious rivers and groundwater, and alternative local currencies. There are makerspaces, mesh network WiFi systems, and platform cooperatives. Language itself is a commons, free to anyone to use, but whose letters and words are fast becoming proprietary trademarks. (Page 1)

The 2008 financial meltdown and decades of market/state inaction on climate change make clear that the dogmas of market individualism, private property rights, and unfettered markets cannot, and will not, deliver the kind of change we need.

§

In the modern industrialized countries of the world, the commons tends to be a baffling, alien idea. The word may be invoked to make faux-genteel allusions to Merrie Olde England (“Coxswain Commons Apartments”), but otherwise it has scant currency. We don’t really have a language for naming commons — real commons — and so they tend to be invisible and taken for granted. The commons is not a familiar cultural category. (Confusingly, “commons” is both the singular and plural of the term, and some people make things even more confusing by using the word “common” instead of “commons.”) Anything of value is usually associated with the “free market” or government. The idea that people could actually self-organize durable arrangements for managing their own resources and that this paradigm of social governance could generate immense value, well, it seems either utopian or communistic, or at the very least, impractical. The idea that the commons could be a vehicle for social and political emancipation and societal transformation, as some commons advocates argue, seems just plain ridiculous. (2)

§

The 2008 financial meltdown and decades of market/state inaction on climate change make clear that the dogmas of market individualism, private property rights, and unfettered markets cannot, and will not, deliver the kind of change we need. And yet the traditional advocates of reform, liberals and social democrats, while generally concerned with market abuses and government malfeasance, are themselves too timid or exhausted to imagine new paths forward. They are too indentured to the market/state mindset and cultural outlook. (I use the term “market” in this context to refer to large capital-driven markets conjoined to our neoliberal polity: a realm of predatory monopoly, concentrated political power, and exploitation — rentier capitalism — and not Adam Smith’s idea of free exchange among equals in transparent, open markets.) By accepting the power of finance capital and corporations, many professed liberals are not really willing to fight for new forms of governance and political transformation. They are content to muddle through with political marketing and buzzwords while clinging to sinecures of privilege.

Countless real-life commons provide a vital counterpoint. By stewarding the gifts of nature and hosting online collaborations and various forms of mutual aid, they enact new configurations of power, governance, and aspiration. They integrate economic production, social cooperation, personal participation, and ethical idealism into a powerful single package of self-help and collective benefit. The commons is essentially a parallel economy and social order that quietly affirms that another world is possible. And more: we can build it ourselves, now. (4)

Bird's eye panorama of Manhattan and New York City in 1873. "The traditional understanding of the commons focuses on natural resources like forests or fisheries. However, the concept has expanded to include various domains, including the urban environment. The "city as a commons" framework recognizes that cities are complex systems with shared resources like parks, streets, public transportation, and even the Internet within city limits."— Jay Walljasper. [o]

§

These movements — for degrowth, the social solidarity economy, cooperatives, transition towns, agroecology, relocalization, peer production, alternative currencies, racial justice, decolonization, Indigenous cultures, the Wellbeing Economy movement, and many others — are in effect creating a new type of “parallel polis,” one that will eventually force a reckoning with the market/state leviathan. This is no ideological pipe dream. It is a piecemeal revolution of real, functional alternatives being built by savvy, pragmatic innovators working largely beyond the gaze of mainstream institutions.

§

Agriculture and food are a massive realm of commoning, for example. Tens of millions of Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities live in entangled cocreation with their local landscapes. Their cultures are profoundly integrated with the life of the soil, seeds, plants, water, animals, and the cosmos. In their own ways, modern movements for agroecological farming, permaculture, and Slow Food emulate many of these practices and values. They practice mindful care of the land and make sure that any market activity does not degrade the vitality of living systems. Community land trusts and community supported agriculture (CSA) seek similar goals by ensuring affordable access to the land and equitable sharing of the benefits. Land trusts, for example, decommodify land, protecting it from speculative investment and making it affordable for organic, smallholder farming. CSA farms invite the community to share the upfront risks for planting crops and, in return, share the bounty of annual harvests.

Once you come to see the huge variety of commons in the world, you begin to realize the many valuable functions they serve. Commons for coastal fisheries and irrigation water have developed practices to prevent overexploitation of fish and water. Neighbourhoods often take care of public spaces and buildings as commons. Urban projects host Web platforms, Wi-Fi systems, and alternative currencies for mutual benefit instead of private profit. Digital networks are a tremendously fertile space for commons-based innovation…, as seen in countless shareable software programs, wikis, and infra-structures. (20-21)

§

What’s critical in creating any commons . . . is that a community stewards wealth for everyone’s benefit, a process known as commoning. The great historian of the commons Peter Linebaugh has noted that “there is no commons without commoning.” It’s an important point to remember because it underscores that the commons is not primarily about resources; it’s mostly about the social practices and values. Thinking like a commoner means escaping the economistic mindset and its compulsion to quantify and monetize everything and wrap everything in tight envelopes of private property rights. Commoners are instead focused on developing rich and varied relationships with each other, with their care-wealth and the more-than-human world (“nature”), and with past and future generations.

Commoning acts as a kind of moral, social, and political gyroscope holding these elements together. It provides stability and focus. When people come together, share the same experiences and practices, and accumulate a body of practical knowledge and traditions, a set of productive, self-reinforcing social circuits emerges. They manifest as enduring patterns of social energy that accomplish serious work and provide ongoing benefit to the community. In this sense, a commons resembles a magnetic field of social, moral, and spiritual forces. The patterns of “commitment pooling” may be invisible to the untrained eye, and its ability to produce economic, biophysical effects may even seem a little bit magical. But it’s time to face the reality: Commons are versatile systems for organizing productive, reliable flows of creative social energy. (21)

§

It is precisely the decentralized, self-organized, and practice-based approach of the commons that makes it so hardy as a political strategy. It’s harder to co-opt a movement when there is no single cadre of leadership. To put it more positively, a diversified movement rooted in on-the-ground, self-directed leadership can elicit much more energy and imagination than centrally directed initiatives can (which, in turn, are more vulnerable to co-optation). Because commons are usually based in practice, not theory, they can also skirt many of the enervating battles over ideological purity that often plague movements. For many commoners, the point is less about getting the right intellectual formulation than about getting real work done. (207) ≈ç

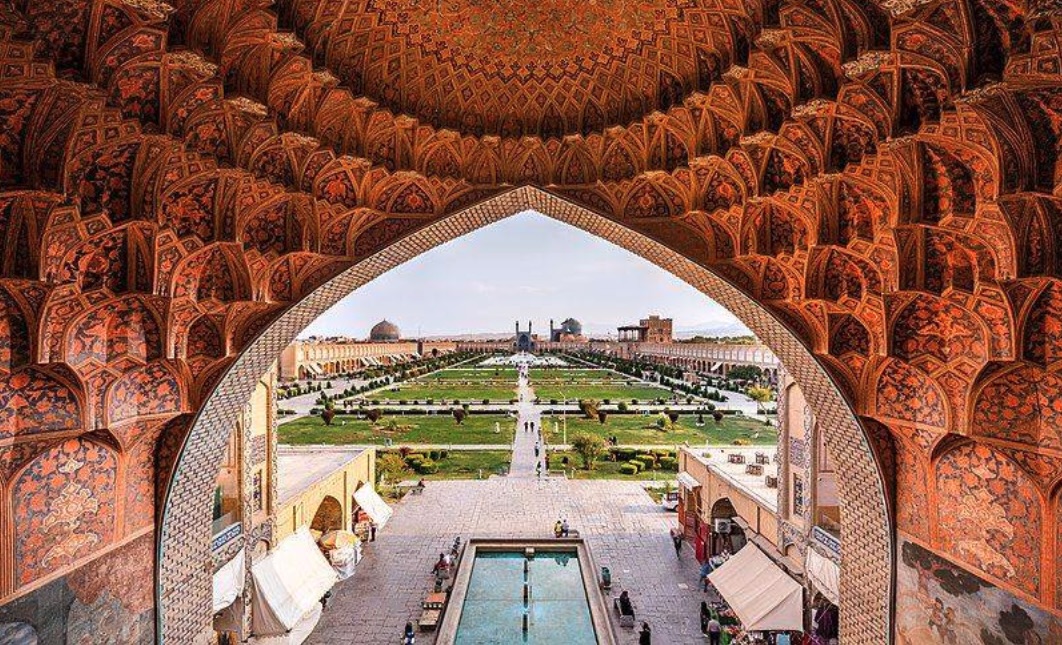

Naqsh-e Jahan Square, also known as Imam Square, situated at the center of Isfahan, Iran. Constructed between 1598 and 1629, it is now an important historical site, and one of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites. Photo: Amir Pashaei. [o]

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID BOLLIER AND CHRIS LOWRY

CHRIS LOWRY Congratulations, it’s great to see a new, revised edition of this unusual book. It has been praised and endorsed by influential thinkers including John Thackara, Richard Heinberg, Susan Witt and Peter Victor. This is not just a book for every economic thinker, but for everybody — a lucid, accessible and inspiring introduction to the commons in all its myriad and wonderful forms, past present and future, and with a very positive future orientation. The territory it covers is familiar to me from my involvement in the local living economy movement of my local bioregion around Toronto. What struck me in my work in this field was how hard it was to sustain these efforts within the pressure cooker of the conventional economy. It's helpful for me to have your perspective of the commons being a social system, and that there are these social capillaries.

DAVID BOLLIER There is no good faith effort that is wasted. Even if they fail, we learn. I came from a Washington activist background working in the public interest world of the 70s and 80s, which was a great political education. But as time went on, as neoliberalism kicked in the 80s and 90s, I saw the limitations of socially progressive business initiatives. Some worked, some didn't, but on the whole it wasn't transformative. I don't want to sound simplistic or that it is a panacea, but when I discovered the idea of the commons in the late 1990s, I came to understand that the commons was not simply an ideological or notional idea. There were lots of people who were doing “commoning” through social practices without names — the way indigenous peoples, open source communities or academic knowledge communities do, to take only a few examples. But none of that stuff was quite validated or recognized as, to use an economic term, value-creating generative activity. So that's sort of how I came to see the commons, and a number of thinkers helped me understand it. I was also fortunate to fall in with a lot of Europeans who have a far deeper, more sophisticated intellectual and political sense about this. Albeit, maybe not with the American can-do pragmatism and optimism that I brought to the table.

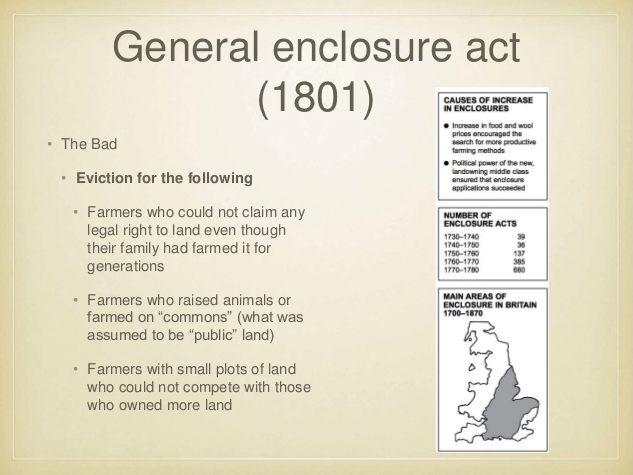

LOWRY A key concept in your work, enclosure of the commons, originally referred to powerful private interests in the distant past, particularly in England. But you use the term much more broadly. Can you explain the many forms of enclosures in the world today?

BOLLIER In essence, enclosure is a capitalist phenomenon that capitalists think of as “development and progress.” But as frequently, as so many commentators and historians are showing, enclosure is an act of dispossession and disempowerment — the way colonialism was, the way the genocide of Native Americans was. In a lot of this, there's a coercion involved in getting the capitalist system going. The original English enclosures were precisely that: the act of evicting people from their traditional communities and relatively stable — especially ecologically stable lives — to convert their lands for use by the industrial machine. Since enclosure is about the privatization and commodification of shared wealth, it can be turned into fodder for capitalist accumulation.

Though it might seem utopian, I saw the commons as a way to identify practical alternatives against certain capitalist premises that we have deeply internalized in our economies.

LOWRY There are some contradictions that I want to explore with you. First, you talk about a “parallel polis” functioning outside of the market/state system, and second, you also talk about the “commonsverse” — that functions within the market/state system — with lots of successful examples. While you present these two, you appear to be oriented towards an aspirational future transformation.

BOLLIER Absolutely. Now, you know, there's aspiration and there's aspiration. I like to think that these are practical and doable because they don't necessarily have to thread the needle of electoral politics or law.

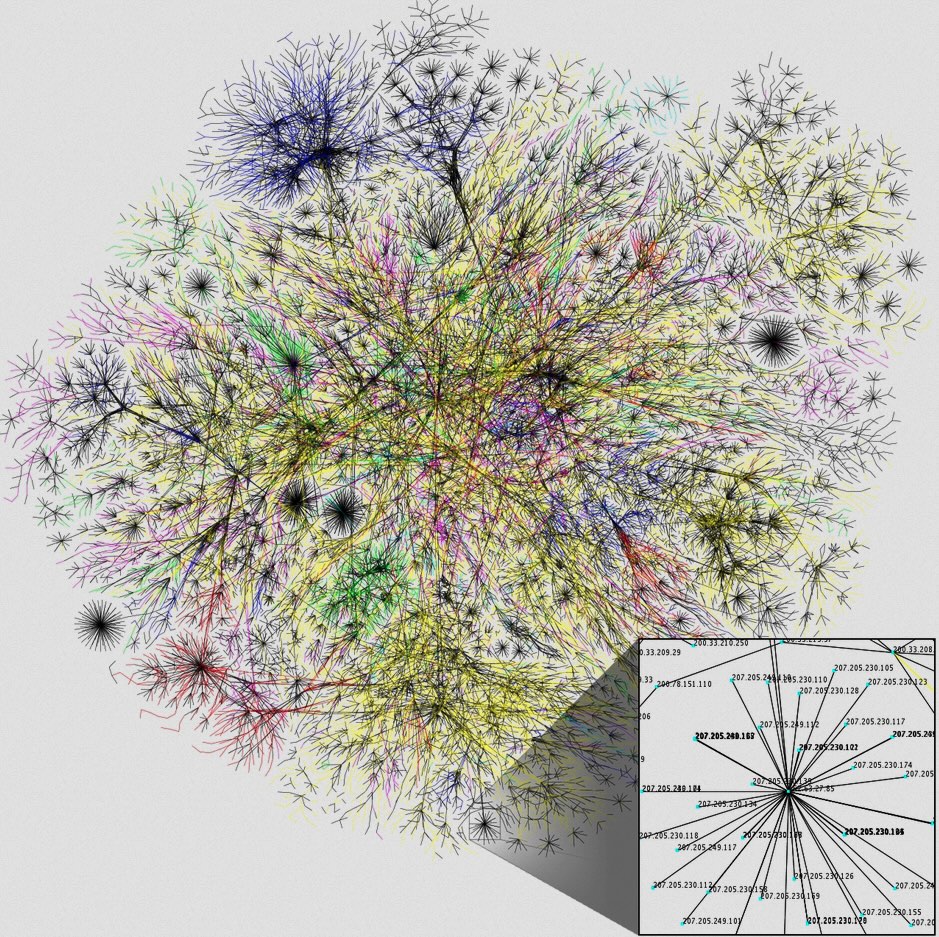

"The internet, in its initial design and many of its uses, embodies the concept of a "commons" – a shared resource that is collectively managed and accessible to a community. This is particularly true for the open infrastructure and collaborative development that has shaped its early evolution." [o]

They sometimes do, but there are things that we could do ourselves. And in fact, most “commoning” has occurred in a kind of self-organized fashion without the benefit of finance, law, the state, and so on. It's an ultimate voluntary association de Tocqueville-style, but it's not captured or dominated by what I call the market/state system, which has its own imperatives, its own desires.

I find this a very compelling analysis of our predicament. And that's one reason why I see that the focus for change has to be much more than resistance to the current system and electoral politics and so forth. Those are necessary, and I don't in any way want to denigrate them, but it doesn't have the strategic amplitude that is needed to grow a different society and get out of the box we're in.

LOWRY You say you don't want to denigrate it, and I appreciate that. But in the book there is a very strong and valid critique of liberalism — and the myopia of liberalism. Please elaborate.

BOLLIER Liberalism has not fully owned up to the fact that it's in a deep alliance with capital interest. Both of these privilege atomistic individualism, contractualism, property rights. They separate us from each other. They separate us from nature as an object, as opposed to a living thing.

Having said that, there's a lot of things about liberalism that I greatly prize and want to salvage, you might say. The things that the Magna Carta 800 years ago enunciated, from due process and habeas corpus to certain forms of limitation on state power.

We've seen how liberalism, whether in the broad philosophical sense or in the more partisan Democratic Party sense, isn't speaking to people's hearts and minds. or to localism or decentralized complexity. The universalism and legal proceduralism that liberalism celebrates have limits and, in fact, are often a dodge for baser motives by the people who have the money to game the system.

I don't see liberals trying to think through how the great things about liberalism can be perhaps repurposed, reframed, renovated, responsive to people's deeper heart and soul. This is a real quandary that needs to be addressed.

LOWRY In the first commoning example that you give, the subsistence farmers in India that have a collective need to manage a resource, it’s a struggle for survival for them, which doesn't necessarily speak to people in more comfortable circumstances. At the same time, you mentioned that these efforts are often regarded by conventional economists as trivial or invisible.

BOLLIER You're right that commons are frequently of necessity — a strategy of survival, even desperation, for people who don't have access to certain overhead expenses that the market requires. But there are also commons developing for open source software, or community-supported agriculture or community land trusts. We can name dozens of these kinds of things ‘barefoot economics’, and they are examples of the deep propensity of human beings as a species to be cooperative. To this point, evolutionary scientists, biologists, ecologists, even physicists are starting to see that relationality is how life works. Rather than individual essences that are separate, which is a fascinating shift.

I see the commons as a relational social organism as opposed to a resource in the way politicians will say, “Oh, the internet or outer space or the oceans are commons.” Well, no, they're a potentially shareable resource, but they're not managed as commons as a social system. And it's kind of a throwaway line to say, yeah, ethically or morally, I'd like it to be a commons, but we the nation state or we the corporate world can't get our act together to run it that way, because we have other priorities. So, I see commons as relational phenomena happening at all levels, from subsistence to middle class to techies.

LOWRY Your chapter on the tragedy of the commons is fascinating. As you say in your book, everyone has the rumour of [Garrett Hardin’s 1968 essay, “The Tragedy of the Commons”] if they studied it in the course of political science or economics or sociology, and it's still out there, really baked into the academic culture in North America at least. But you say that Hardin got it wrong. How so?

BOLLIER Well, first of all, he wasn't describing a commons and a lot comes down to that. He was describing a commons by the lights of conventional economics. Because it's not a place of market activity, it's regarded as “waste lands” or a place where it's trivial or subsistence, but not generative. He regarded a commons mostly as a resource that was an unsuccessful management regime because nobody would individually find it rational to hold back and not take more. This was frankly a “just so” story or fable because it had no empirical grounding presented in the essay, which became the celebrated truism [of inevitable failure] within economics, poli sci, sociology, and so forth.

But it simply mirrored the interest of capital and business to regard commons as a non-entity and therefore a regime of private property should govern instead because that's the only way to responsibly manage resources. It was an ideological fairy tale. Eleanor Ostrom, the political scientist at Indiana University in her pioneering studies on commons showed that a commons is quite different from what Hardin was describing. In a functioning commons there is a bounded community with rules, with punishments for those who break the rules, with other ways of coordinating activity precisely to prevent the overexploitation of shared wealth.

In other words, in real life, people talk and communicate and work it out and figure out how they can do it as opposed to saying, I'm going to take all I want. Hardin was describing an open access free-for-all, not a commons.

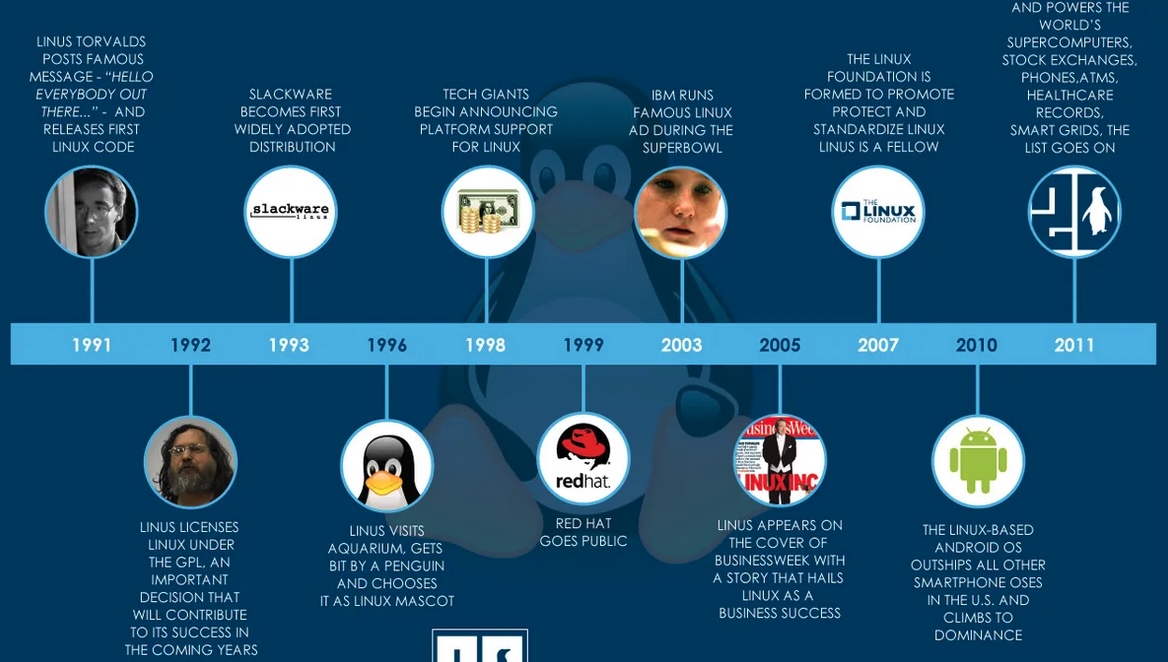

And that's why Microsoft's president in the 1990s, called Linux communistic, because open-source software, he properly understood, was a threat to their business model of private control, as opposed to hackers coming together as a group, a big network, as enabled by the internet.

LOWRY You also added that the real tragedy precipitated by scheming individuals is not the tragedy of the commons, but the tragedy of the market. Can we go with that?

BOLLIER Well, absolutely. Because the market is the laissez-faire libertarian individualist regime which Hardin was describing. And we've seen in countless ways how that behavior does result in the over-exploitation and destruction of what is ethically, at least, our shared wealth.

So here we are. In my studies of the commons, I found that a lot backs up to the language we use and the perceptual frame by which we understand things. And so, for example, in the commons, I found it difficult to talk about resources because that immediately distances it from me or the commoners and objectifies it as a commodity. Whereas in a commons, you have affective relationships with it. You love it. You've nurtured it. You've stewarded it. Your culture and your cultural identity may depend on it, the way indigenous people have deep affiliations with a landscape or a river. And so, in a commons, I don't even like to talk about resources, even though, of course, functionally commoners still use resources, because there's an intersubjective dimension in a commons that makes everything connected with you.

LOWRY One of the conclusions that I draw from your description of Ostrom's work is that the commons are not, by definition, anti-capitalist, but capitalism is anti-commons.

BOLLIER That's a lovely way to put it.

LOWRY We certainly see it in India, where the alliance of government and big agriculture has driven, over the years, many, many thousands of subsistence farmers to kill themselves in protest. So, is that a reasonable extrapolation to make?

BOLLIER That accusation has been made in that circumstance, but I would agree with you that capitalism is kind of an engine of separation and individuation, and it works against our coming together, one, because you can't make as much money that way, as opposed to segmenting the market, two, because people coming together represent a different locus of moral authority, if not political threat. And that's why Microsoft's president in the 1990s, called Linux communistic, because open-source software, he properly understood, was a threat to their business model of private control, as opposed to hackers coming together as a group, a big network, as enabled by the internet.

So, this is a recurrent phenomena of how capitalism works. It likes to embrace the idea of a sharing economy, which they touted 10 years ago, but in fact, it was a micro-rental economy for individuals. So, there's a struggle going on here between collective affirmations of identity, aspiration, meeting needs, and individual market versions of that.

Linux, invented by Linus Torvald, is a free and open-source operating system that is widely used on a variety of devices, including computers, servers, and mobile phones. The source code for Linux is publicly available, allowing anyone to modify, distribute, and use it.

LOWRY Something that really surprised me, blew me away in your book is that 90% of sub-Saharan Africans don't have statutory title to their lands, and they are at constant risk of being displaced. I did see a documentary from northern Kenya last year about some traditionalists and their struggles with the white settlers who were granted these vast swaths of the best land, and there were border skirmishes, violence, and it was ongoing, and it was very painful to see. It’s amazing to realize that two billion people in the world have only customary usage to their lands. A quarter of the world's population are land-based commoners.

BOLLIER It forces you to reflect on the ethnocentrism of the West and Western jurisprudence, that those norms should be universal, but of course, you know, they're selectively applied or the state and investors collude to get Western jurisprudential title to the land, and just run roughshod over customary claims that have been in existence for generations. And you're right, it's a huge injustice, and it's one of the reasons why the struggle between the global South and indigenous people against neoliberal trade regimes and extraction is so pivotal for this moment.

LOWRY Your chronicle of the enclosures of nature was very good. And I just wanted to read this paragraph back to you:

The range of enclosures of nature is vast and expanding. They extend from the global (the atmosphere, the oceans, outer space) to the regional (groundwater, aquifers, fisheries, forests) to the local (native foods, hometown traditions, independent businesses). Enclosures also include living things (cell lines, genes, genetically engineered mammals) and infinitesimally small things (microorganisms, synthetic substances, or nanomatter).

BOLLIER Well, you know, the capitalist project sees money-making opportunities everywhere, especially if they can get a monopoly right through patent law, for example, to a product or to a realm. And that little list is just sort of an example of the different ways in which the natural world in our lives has been marketized. And to be sure, there's been some good things that have come from that in terms of medicines, perhaps.

But I'm just suggesting that the kinds of innovation we've had have come at a huge cost. And there's other ways in which similar innovation can be done without being so monopolistic or extractive.

LOWRY Your critique of green capitalism is pretty devastating.

BOLLIER We're not going to work our way out of an ecological crisis through technological innovation and market expansion or innovative finance alone. And in fact, some of those are simply cover stories for the same old, same old. So, this is the dilemma we're in.

While I don't want to deny the benefits of some green markets, I do want to say that it's not changing the overall systemic logic. That's why I concentrate on the commons as an alternative socioeconomic logic that doesn't have the growth imperatives, that tends to be more fair and humane. And, you know, perhaps we'll point the way to a different way of being while meeting our needs.

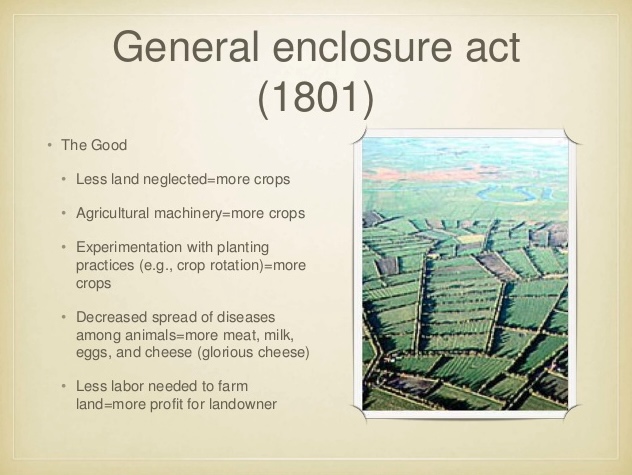

“Enclosure of common land was a process which produced much resentment by the rural poor who often depended on this land for grazing of cattle, horses etc and collection of firewood." [o]

LOWRY Your efforts to tease out the deeper roots and meaning of the commons, and your use the word “communing” as a verb are important. You say “it's ultimately experiential, historically situated, and based on relational dynamics, …best understood as peer-organized social phenomenon.” Can you tell me more about that in plain English?

BOLLIER Well, it's when people get together and say, we want to manage the shared wealth for our mutual benefit and steward it properly to sustain it. I mean, that sort of comes down to, it's in some ways that simple. It's, of course, more difficult because some resources get used up and others like digital code can be almost freely shared.

So, there's a lot of complications that immediately ensue, not only with the so-called resource, but among people. How do you get a people who have diverse talents, experiences, temperaments to be more or less aligned and pull together, albeit despite their differences? I mean, I know it's difficult, but I've also seen some pretty large commons that are almost, when you see them in action, that work, it's sublime.

The winner of the 2022 Right Livelihood Award was this Venezuelan federation of co-ops called Cecosesola. They consisted of a farm-to-produce market, agriculture operation, health care, many, many other co-ops, but they did not function as a employer, employee dynamic but as people who, without a sense of sanctimony at all, saying, we're in this for mutual ethical improvement and responsibility. And they behave that way — a trust-based operation. And some of the people got upset when they introduced cash registers because they saw that as undermining the trust of the whole organization.

When you see some of these examples of success, certain open-source communities, certain co-housings, certain co-ops even, although they might swing towards the market way and become a quasi-corporation, they can be an incredible social mission-driven enterprise. When people come together, sometimes you have this remarkable sense of shared purpose and effectiveness at the same time.

LOWRY Towards your conclusions in your book, you point to the fragility of our large market-based systems. You suggest that the social trust, the stability and the credibility that global and national markets need in order to function haven't really fully recovered in the 18 years since the 2008 crisis. Now, with what Trump's doing, blowing up all these norms at a whole other scale and intensity and everything, do you see opportunity or doom or both?

BOLLIER Well, I'd say both, in the sense that there's going to be very painful, harmful disruptions occurring.

It's already occurring. But sort of like the way nature opens up spaces for new growth and innovation when a meteor hits the planet or there's an earthquake, that's what we're going to experience. And there will be new opportunities. It doesn't feel quite the right word, but new spaces for developing things that were previously impossible because the system was locked up so tightly. Trump is destroying that.

I would not wish for that. I would wish for a more reasonable transition. But that said, if people are going to have to survive and they're going to have to innovate to survive, we've already seen things like the mutual aid networks in response to the pandemic provide that kind of interesting innovation.

People will start to realize they're more interdependent on each other and on the earth than they realized. Global supply chains that are volatile and expensive might not be the best answer. So yes, there will be opportunities and there's going to be a lot of pain.

I heard a great phrase the other day about how new thinking is not going to lead to new ways of living. New ways of living are going to lead to new ways of thinking. That we're going to live this first. People are going to do this without the benefit of theory or establishment intellectual frameworks. They're going to invent the way so many commons have been invented out of nothing. And then, of course, complications will ensue, hybrids will develop and new ways of thinking occur. ō

LINKS

• Grassroots Economic Organizing

• International Association of the Study of the Commons

DAVID BOLLIER is an American activist and scholar who studies the commons as a new paradigm for reimagining economics, politics, and culture. He has been Director of the Reinventing the Commons Program at the Schumacher Center for a New Economics (USA) since 2016. He has written or edited eleven books on the commons. He lives in Amherst, Massachusetts. View David's website or tune into his podcast, Frontiers of Commoning.

CHRIS LOWRY is a media producer and singer. His most recent documentary feature is Rebel Angel, about the Canadian literary and culture critic, Ross Woodman. As part of the original team that created the print version of The Journal or Wild Culture in 1986, he served as senior editor from 1986 to 1989. He lives in Toronto where he performs regularly with his band, The Cool Blue North. View Chris' website.

Add new comment