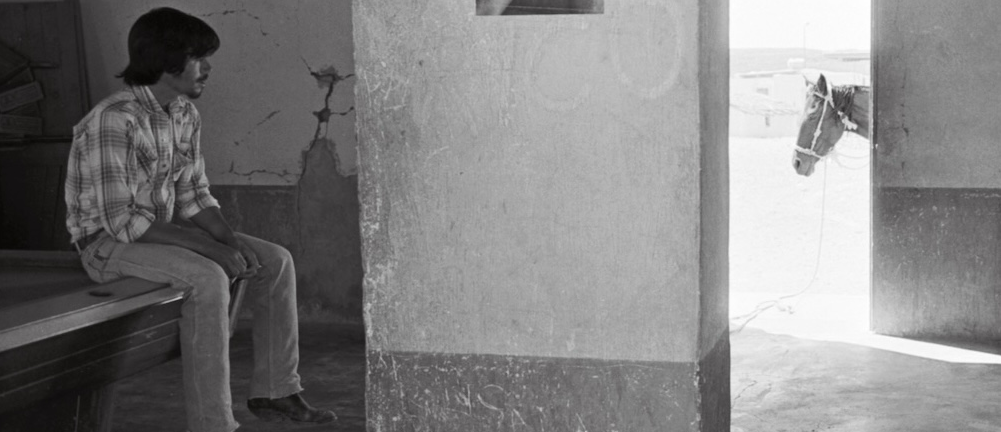

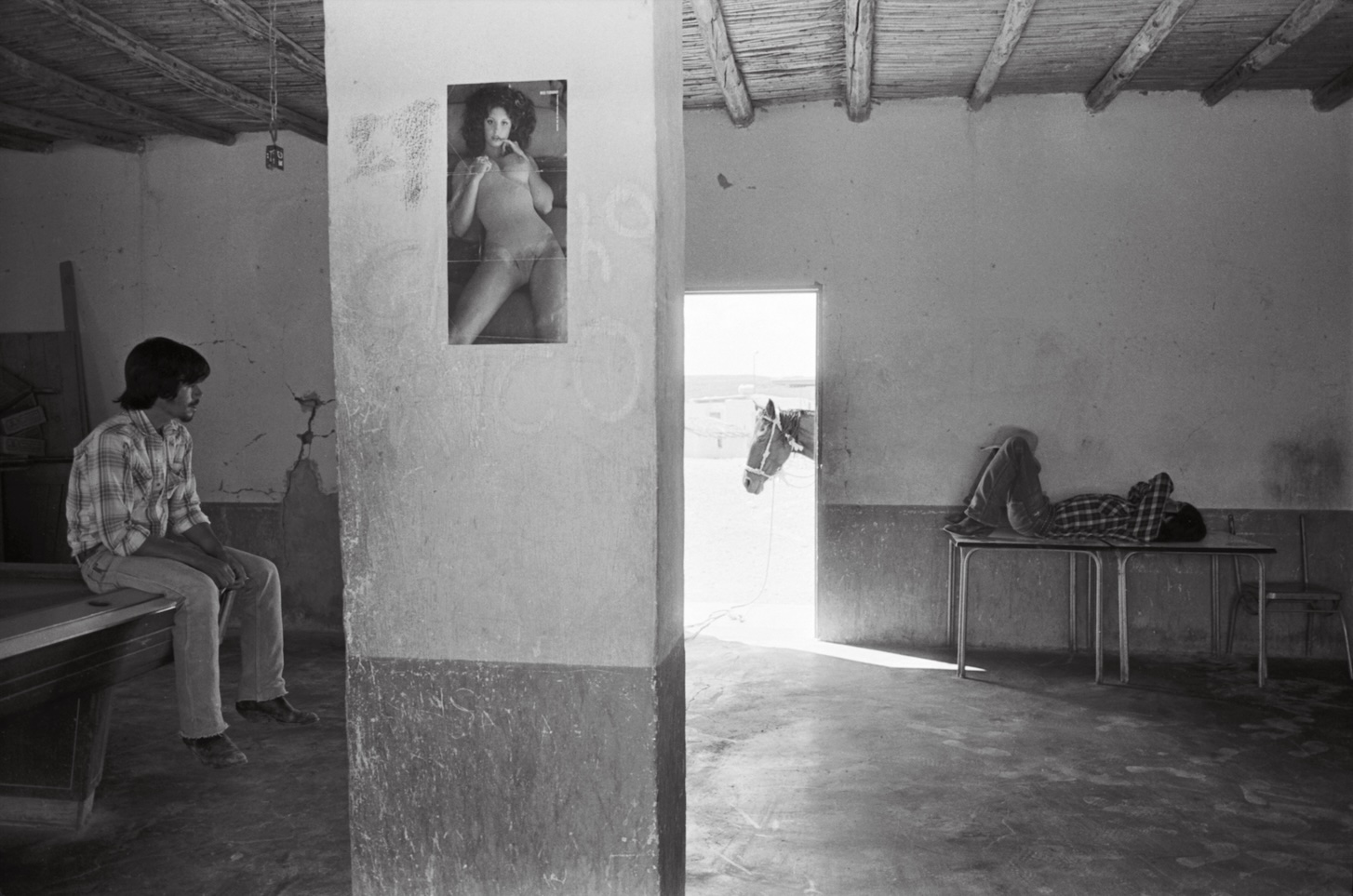

'Bar, Northern Mexico' (inset). 1984.

It takes courage to grow up and become who you really are. — e.e. cummings

When I was 10 and my parents were out for the evening, long after I should have been in bed, I sat at the top of the carpeted stairs looking out the window for the headlights of my parent’s car. Meanwhile, my sister was entertaining her boyfriend who had snuck in the side door as my parents left through the front. Should my parents’ car turn from the roadway into the driveway, from this position I could watch the driveway and holler to my sister. I watched headlights come up the street and pass by. I watched a dog with his owner stop in front of our bushes and lift a leg. I watched across the street as lights turned off on the first floor and my friend Anita’s mother and father climb the stairs. I watched the TV turn on in their bedroom. I could tell from the blue light it radiated. I watched for hours. I was the lookout. My role as a watcher started early.

Without a camera, I made a picture in my head. I have seen it before, and some day in the future I will see something like it again.

I have remained a watcher, a voyeur. I recognize things as they happen — the way people touch or look at or speak to each other. I watch gaggles of girls in their school uniforms pour onto the subway, collapsing over each other. I'd have photographed it if I’d had a camera. Instead, in my head, I frame the picture. I make a lot of phantom pictures this way. Later, when I do have a camera, I will shoot something that recalls my phantom photograph of what I saw that day on the subway.

Why photograph at all? How does photographing something help me see? How does it help me get through my life? From years of considering these questions I have found that my choice to photograph perfect strangers is motivated by me recognizing something of myself in them.

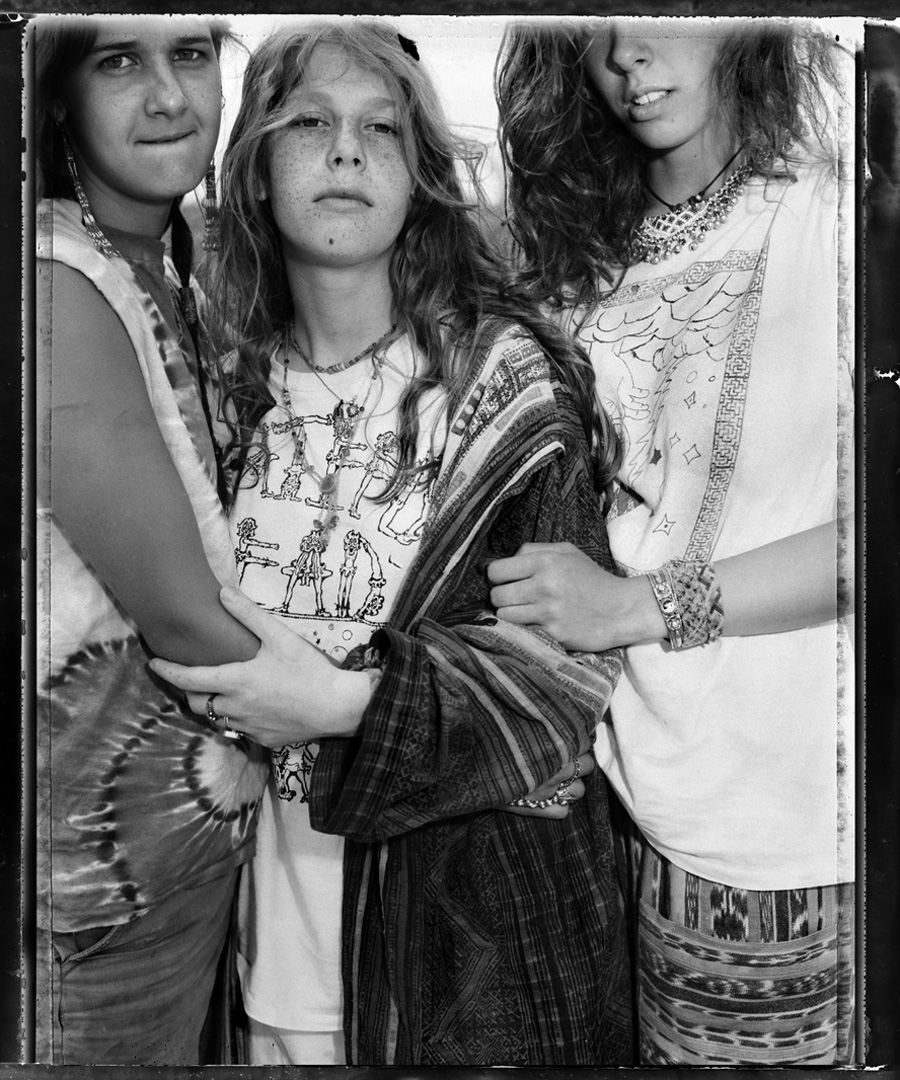

'Deadheads.' Buffalo, New York, 2006. They could be sisters. Or witches. A coven of three. One bites her lip like she knows something I don’t. The one on the right half-smiles, half-dares. But it’s the girl in the center who meets me directly—freckled, fearless, already sovereign. Their arms form a circle, a closed loop of allegiance. I was only ever invited in briefly.

About 30 years ago, I started photographing young people, mostly teenagers. I recognized in them their engagement with the act of becoming. It also felt familiar to me. So my main goal was to capture something of a time of life that can be complicated and fraught as much as it can be euphoric. How can I make a picture that exposes something tender or troubled about teenagers — and how might I visualize the delicate balance between the two. Photographs are always of something, but, ideally, they will also be about something. The photographers I love are able to do this. Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander, my early influences, were able to organize disparate elements in a three-dimensional world (what I’m seeing) into a two-dimensional space (the photograph) that reveal small truths about the people and spaces these photographers encountered.

For me the best photographs have a fractured sensibility where elements in the photograph are working at cross purposes with each other. The teenagers I am drawn to are, to me, insisting through their costume, gesture or posture to be regarded as distinct, while at the same time trying to disappear into the sameness of belonging. I see that push and pull as at the core of being a teenager.

'Street Dog.' Chicago, 1984. Chained to a bumper above a storm drain, the little dog waits in the shadow of a slogan: Be All You Can Be. The leash is taut, the street cracked, and everything feels one tug away from unravelling.

Roland Barthe, the French theorist, described photographs as having a very particular dynamic, something he referred to as studium and punctum. It was a way to discern, to understand an image. As he defined it, studium refers to the information the photograph presents, helping us as viewers to understand what we are looking at. What is the location? What are people wearing? Where are they standing? How are they standing? What does it all say about them? But it is the punctum that will carry the picture. Punctum is a small detail in the photograph that maybe changes how we interpret the picture and the people in it. An untied shoe perhaps, as Barthe suggests in his book, Camera Lucida — a detail you might overlook but that gives the photograph its efficiency of connection with the viewer.

It is lunchtime in the concrete yard of a middle school. A young boy in a short-sleeved white shirt wears pants that are too short as he kicks at the gravel with his shoes which seem too big for his feet. I watch him wander aimlessly making wide circles on the pavement. He stoops to pick up a stray leaf that he holds between the fingers of his hand delicately, gingerly. This stops me and I ask if I can take his picture. He stands straight and tall and poses for me. The leaf in his hand is, for me, the detail that tells me what I want to know about him — an object that speaks to the tenderness in him. His interest in a leaf lying on the ground is now in his hand. This is a public school and school uniforms are expensive. The drape of his pants, a few inches above the ankles, suggests they might be from last year. Maybe he can get another semester out of them. The shoes look new and too big for him, but he will grow into them. What can I speculate about the economics of sending a boy to school when money is tight? As a photographer, recognizing elements coming together like this is a reflex that I act on. Trying to decipher what I am looking at only comes after the picture is made — later I can see why I might have been drawn to him in the first place.

'Seth, Boy with Leaf.' Dellwood Middle School, Bermuda, 2017. I asked him to stand still and he obliged, proud in his school uniform, polished and proper. But it’s the leaf—held so casually in his fingers—that stops me. A small, bright rebellion in an otherwise formal frame. I didn’t notice it at first, but now I can’t look away.

'Seth, Boy with Leaf.' Dellwood Middle School, Bermuda, 2017. I asked him to stand still and he obliged, proud in his school uniform, polished and proper. But it’s the leaf—held so casually in his fingers—that stops me. A small, bright rebellion in an otherwise formal frame. I didn’t notice it at first, but now I can’t look away.

Yesterday I saw a young couple in the park, sitting on a bench. She was gazing into his face while he worked at rolling tobacco into a cigarette in his lap. He was distracted. She was riveted. Without a camera, I made a picture in my head. I have seen it before, and some day in the future I will see something like it again. A young woman besotted. A young man, disengaged from her in that moment — she, longing for his attention. But do we ever get what we want and need when we want and need it. Perhaps this picture might have been about that.

Photographs are a kind of talisman for me. They hold memory, love, grief, recognition, defiance, vulnerability, restlessness. In the photographs I make I am carrying my past, my longing, my unfinished business. Although I am not in the frame, I sometimes see my younger self and the children I have raised in the young subjects I cast my gaze and lens upon. Perhaps they show me something I need to see, and that’s why I was drawn to it to make a picture.

The art of photographing someone may be as simple as saying: I was here and so were you. ō

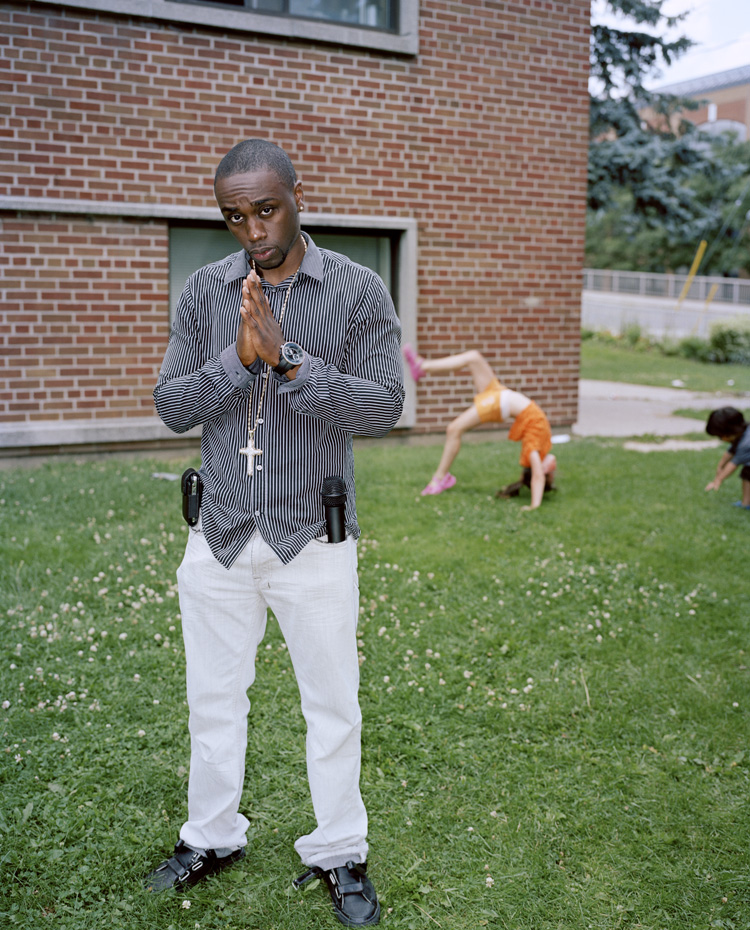

'DJ with back flip girl in background.' DJ Jaydahman at Lawrence Heights Revitalization BBQ, 2008. His stance is practiced. Every detail chosen, from the chain to the gaze to the way his hands press together like a benediction. Behind him, she flips through the frame, all motion and joy, as if no one is watching. Maybe that’s the balance: curated cool in the foreground, wild freedom in the back.

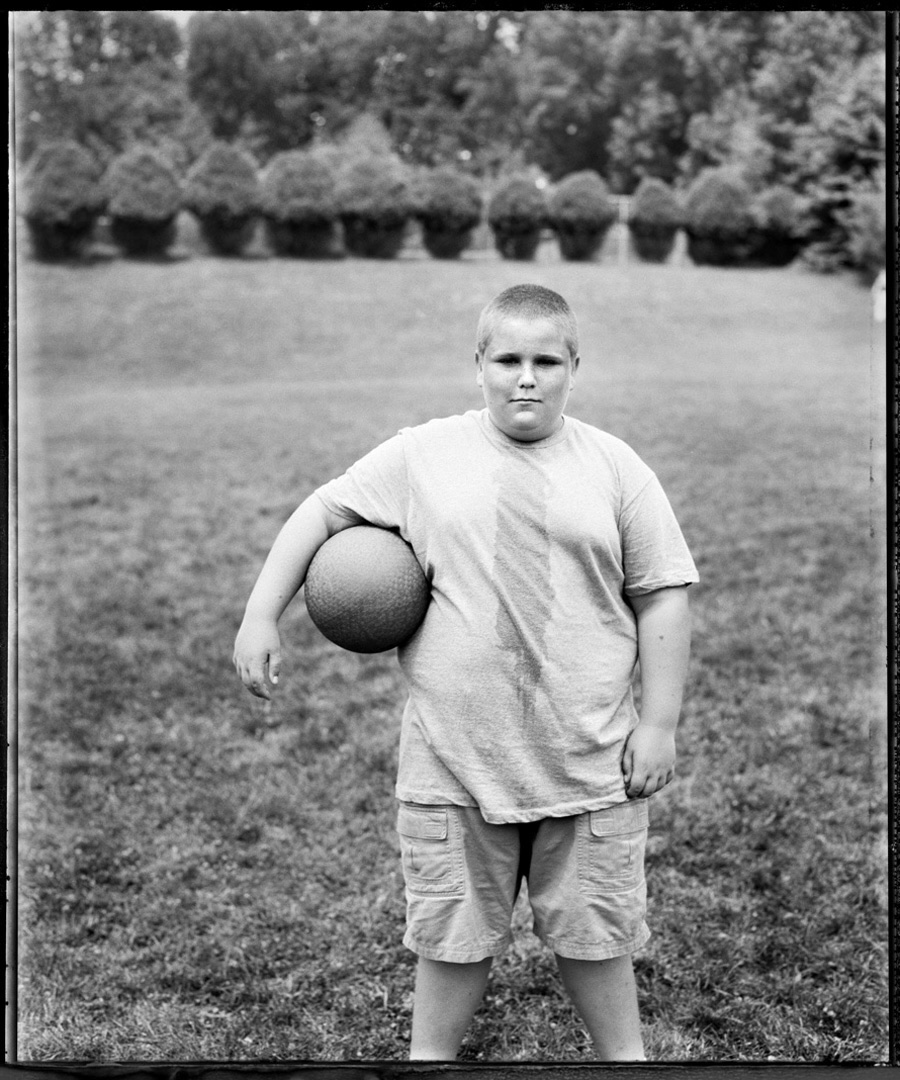

'Fat Camp.' At fat camp in upstate New York, he stood in for me: serious, unsmiling, and drenched with effort. Behind him, the bushes line up like oversized muffins cooling on a windowsill, a surreal backdrop to this portrait of determination, defiance, and the complicated weight of becoming.

'Bar, Northern Mexico.' 1984. Everything here feels paused—two men, a waiting horse, a heat-struck room where even the pin-up seems wilted. A portrait of waiting, of masculinity caught in stillness, of time slowed to a standstill.

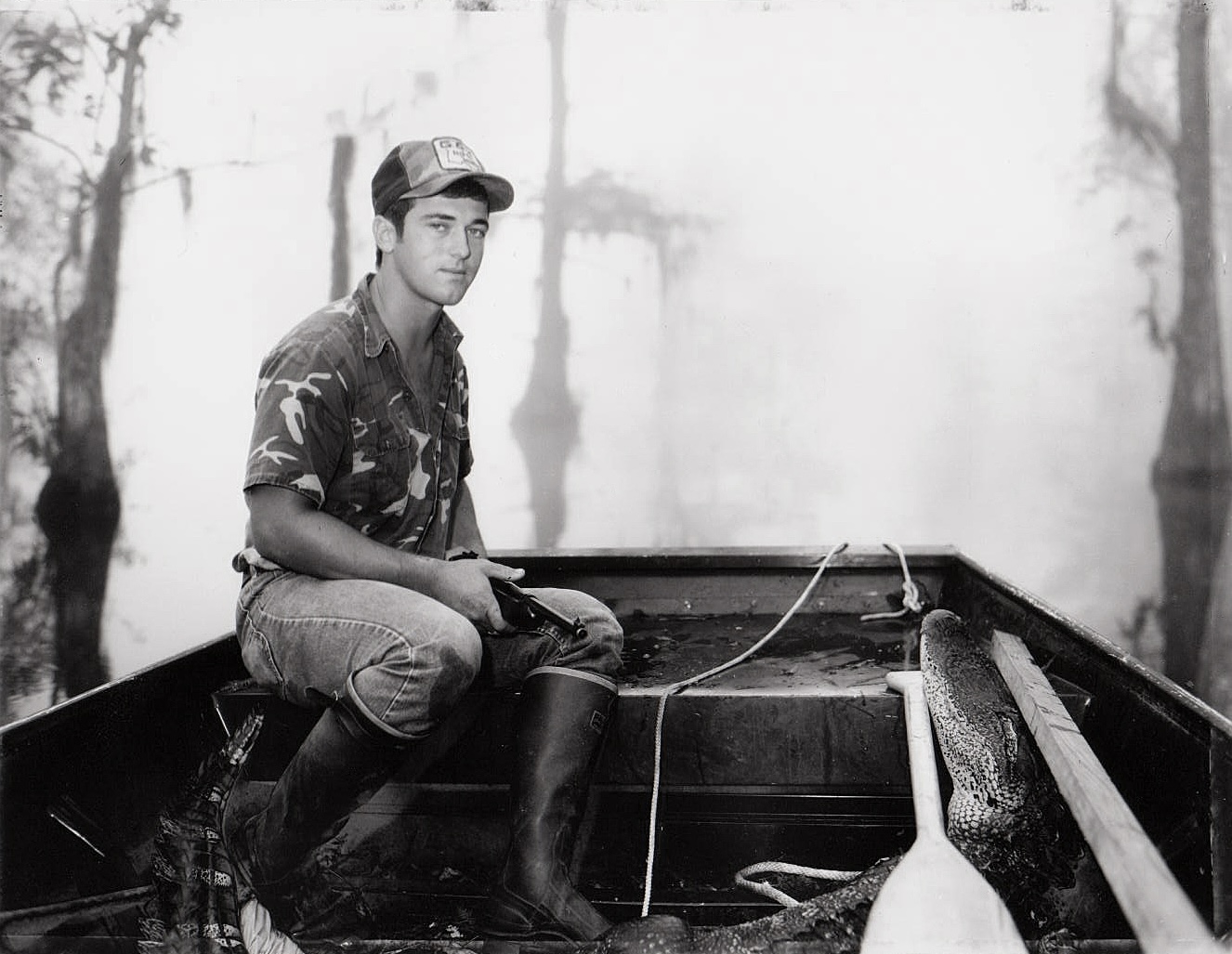

'Alligator Hunter.' Ville Platte Louisiana, 1985. It looks like a studio portrait—fogged glass, perfect light, the subject composed just so. But we’re deep in the bayou, not behind a backdrop. He’s got the face of a high school quarterback, all softness and youth, but there’s a rifle in his hand and an alligator at his boots.

'School Girls in Neck Ties.' (Diptych.) Cedarbridge Academy Student, Pembroke Parish, Hamilton, Bermuda, 2017.

DEBRA FRIEDMAN is an internationally exhibited photographer and photography educator, and the recipient of numerous visual arts awards from the Polaroid Corporation, the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Debra has enjoyed several artists’ residencies, notably at the Hambidge Center in Rabun Gap, Georgia and the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art, Bermuda. She lives in Toronto.

Captions by the author.

Comments

Wonderful images, eloquent…

Wonderful images, eloquent reflections.

"Already sovereign". Wow!

"Already sovereign". Wow!

These are a stunning series…

This is a stunning series of poignant images with writing that educates as it elucidates. I think I may finally understand punctum and studium! Incredibly moving and in the style of the photogs that are mentioned here as artistic influences—mirror us and help return some lost humanity at this time, here, now. Empowering to be reminded of how seeing is an act implying framing moments — and we all do it.

Add new comment