Artisanal antithetical — living the paradox.1

OJAI, CALIFORNIA — In the burgeoning bohemian capital of Ojai (as Architectural Digest gushes in a recent blog piece), we live at the vortex of a luxury market devoted to an ethos of the organic, natural, hand-crafted, and locavore.

There’s no denying the appeal of artisanal foods, small-batch beverages and locally-sourced goods made from natural materials. Yet the market for such products typically exists — in the global north — in wealthy societies underpinned by an antithetical means of production: corporate capitalism.

How do we live with this paradox? The prevailing goods and services and means of communication across the planet are the products of advanced technologies created with the deliberate goal of reducing the amount of hands-on labor involved, and concentrating the profits of such endeavors into the hands of the few.

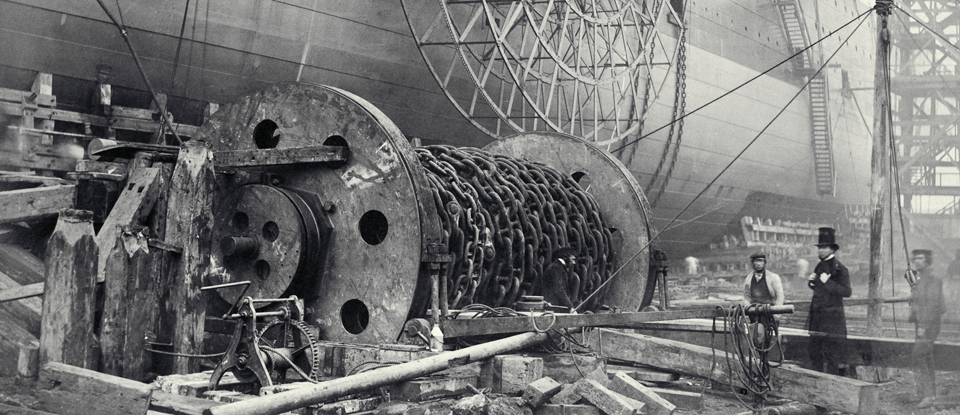

This phenomenon was enabled in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the development of a highly focused and reductive way of looking at the world, the Scientific Revolution, and its practical adjunct, the Industrial Revolution. Advances in weaponry, navigational technologies and transportation enabled peoples from countries who first adopted this new outlook to colonize great swathes of the planet and use foreign labor and raw materials to enrich their own societies. Thus we have the familiar tale of modern civilization: a world founded on the twin pillars of rational scientific analysis and greed. It replaced a pre-modern age of manual labor, hand crafts and food and drink that, even if often scarce, were always organic.

Displaced rural workers have become enmeshed in the modern world as passive consumers rather than as active producers.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, increasing mechanization of large scale agriculture reduced the number of jobs available to rural populations and made available a vast labor pool for the new industries of mass production. A similar process continues to play out in the so-called developing world today. A universe of artisanal production and small, mixed farms of crops and livestock is being replaced by hugely productive, artificially fertilized mono-crop agri-businesses and meat factory farms tied into a global distribution system — enabled by the fossil-fuel internal combustion engine. Displaced rural workers, over the generations, have become fully enmeshed in the modern world overwhelmingly: as passive consumers rather than as active producers.

Yet we continue to crave the organic artisanal foods and hand-crafted goods that once were our birthright. In Ojai and select towns and suburbs throughout California, they are readily available, marketed by an array of local providers. We may even fantasize about a universal reversion to organic farming methods, localized production and hand-made goods. Yet, we are also aware what such a transition might entail: the destruction of corporate capitalism along with all the financial, health, food, communications, transport, scientific research, education and consumer goods that the system supports. For most people too, their livelihoods (and their ability to purchase artisanal luxuries) depend on the maintenance of that system.

Striving to strike a balance against inevitable forces of economic momentum.1

Patti Smith, who played the Granada Theatre in Santa Barbara recently, seems to have an answer. She sang . . .

I had a dream, Mr. King, if you'll beg my pardon

I was trespassing a sacred garden

And the blossoms fell and they dropped like candy

And the nature cried, "Gandhi? Gandhi?"

And the nature cried, "Gandhi? Gandhi?"

And then . . .

Long live revolution and the spinning wheel

Awake, awake is the mighty appeal

Oh, people awake, awake from your slumber

And get 'em with the numbers

Get 'em with the numbers . . .

The numbers are indeed what it is about. The planet’s ability to support over seven billion people depends on the cruel system of production and reward the powerful have devised over the last half millennium and whose viability is profoundly dependent on the ravaging of the natural world — of trespassing a sacred garden.

A hard mind for politics, a soft touch with everything else.2

This week, the chaparral has also spoken. Ceanothus blossoms are heavy and about to drop. Nothing is as sweet in the local elfin forest as buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus) in bloom. The Santa Ana winds of late January have scattered the tiny white petals across the chaparral trails. On still days the sweet scent hangs in the air: anchored by a dark, honey fragrance freshened by herbaceous sage-like top notes, it is redolent of the nose of a vintage Sauterne — of floral candy.

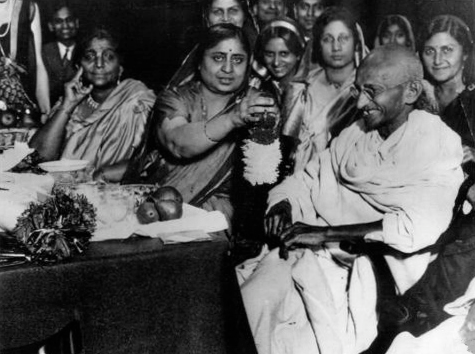

Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) used a spinning wheel as a symbol of self-sufficiency: it represented a way to replace industrially produced clothing with self-spun khadi cloth dhotis, lungis, kurtas and sarongs. His was a vision of self-employed small farmers and craftspeople who lived in small villages rather than cities and derived their livings entirely within the local community; governance, to the extent that it was required, would be organized through consensus driven village assemblies.

Transportation in traditional, rural India is by foot, bicycle and ox-cart. Gandhi saw no need for further elaboration.

Gandhi was adamant in his opposition to the centralized, industrialized, and mechanized modes of production that the British had developed and he fully understood the impact of India’s economy becoming subservient to that system. He preached, “Not mass production, but production by the masses”. Transportation in traditional, rural India is by foot, bicycle and ox-cart. Gandhi saw no need for further elaboration. One of the great symbols of Britain’s command and control of the sub-continent was its vast network of railways: Gandhi understood its true significance as a conduit of imperial power.

We are now, ourselves, mostly colonial subjects of multi-national industrial capitalism: a system ultimately upheld by governments, legal frameworks and militarized police forces. Notions of the organic, natural, hand-crafted, and locavore are a subset of broader concepts of sustainability, localism and democracy. Gandhi’s idea of Swadeshi, or home economy, retains its relevance: there can be no genuine embrace of the local without breaking the bonds of a globalized economy.

Ceanothus blossoms . . . ready to drop.3

Our fetishization of organic food, natural fabrics and homewares fits neatly into the prevailing economic model as a high-end, boutique market ultimately sustained by consumers fully embedded within neo-liberal economics and the industrial modes of production, transportation and communication it enables.

If we are to awake from our slumbers and get ‘em with our numbers, it will take a little more commitment than shopping at the farmer’s market, driving a Prius and enjoying device-free home-cooked meals with our families.

Clouds of ceanothus blossom have emerged from the chaparral. Surely in Ojai we can hear nature’s cries of “Gandhi, Gandhi”? The blossoms have dropped like candy: it’s time to get our dhoti on.

JOHN DAVIS is a California-based architect "living on too many acres of chaparral in Upper Ojai." He writes a blog, Urban Wildland, where he says his writing "is a way of resolving the values it represents; a single voice, yes, but one that is, I hope, always evolving." Indeed it is.

This article first appeared in The Journal of Wild Culture, February 13, 2015.

Comments

But will locavores read this

But will locavores read this article? Will they understand? Or are they so caught up in their selfishness that they cannot understand? The idea of using vast quantities of wood to fire stoneware pots, and then gush over the subtleties of the glazes produced by flashing has always struck me as supremely selfish. Nietzsche was right.

Add new comment