Saint Henry Hermit in prayer, etching by Thomas de Lieu (1560-1612). [o]

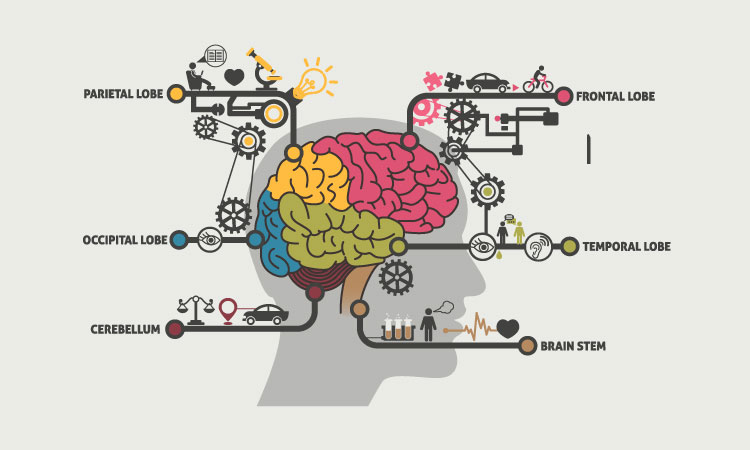

“You can think of meditation as a form of attention training,” said Sara Lazar of Harvard University during a panel at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) last week. The practice involves sustained attention, awareness of your thoughts and sensations, and holding in mind the intention to stay focused. Showing mainly results from studies investigating mindfulness meditation, she described changes in brain structure seen in new meditators after just eight weeks, including increased volume of gray matter and the left hippocampus, and decrease in size of the amygdala.

Long-time practitioners also showed larger volume of gray matter compared with non-meditators of the same age, which could help them into old age, she said. As we grow older, our frontal cortex loses volume, but in the older meditators, certain areas were better preserved. “Meditation might have a bit of an anti-aging effect.”

But the practice facilitates it ... so at some point a person may have an intense spiritual experience.

Mindfulness has been found useful to treat stress, pain, anxiety, and depression, and is being investigated in a host of other areas. People who meditate score better on tests of selective attention, cognitive efficiency, 2-point discrimination, and IQ. It also makes you “better able to stay focused on that really boring task,” Lazar said. “This suggests neuroplasticity to me,” the ability of your brain to change and adapt.

Andrew Newberg of Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital investigates prayer and other meditative processes. He described changes in how the brain functions during the practice and over time, based on imaging blood flow. In people who practice kirtan kriya, a meditation that includes voicing syllables and moving the fingers in a repeating pattern, researchers found long-term changes in the brain at rest: increased activity in prefrontal cortex and a quieting of the thalamus, which is a relay for sensory information.

"The idea that meditation is actually a form of research is gaining respect." [o]

In a separate study of people who attended an Ignatian spiritual retreat, Newberg’s team “observed significant decreases in dopamine and serotonin levels.” Such a calming could make a person more receptive to deep spiritual moments, he suggested. “It’s not the practice itself that is the experience, but it facilitates it ... so at some point a person may have an intense spiritual experience.” Still, it’s early days in research in these areas, he warned. “We are just scratching the surface.”

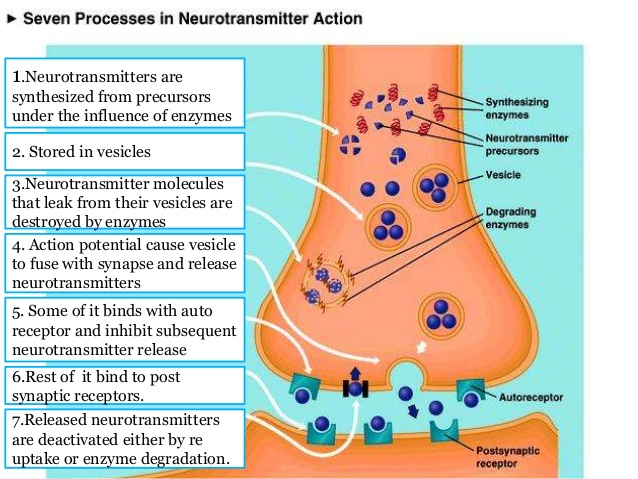

Focusing on yoga, Chris Streeter of Boston University School of Medicine described how this practice appears to help people return faster to internal balance (homeostasis) after stress or threat. Studies tracing the amount of the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid; the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system) found that amounts increased in the brain among practitioners, and they report better mood. It’s hard to tease this apart from the effect of any exercise, which also can increase GABA, though in one study the yoga-doers scored themselves higher in mood than people who walked a commensurate amount.

In a study of people with major depressive disorder, researchers found that “as their cumulative yoga minutes go up, their depression-reported measures go down,” and their sleep improves significantly. “At the end of 12 weeks, GABA is equal to the normal” level, Streeter said. Drugs for depression usually target the monoamine system, not GABA," she said, "so people can do both without a problem."

“One of the questions we need to answer is what’s regulating what?" said Newberg. "What’s influencing what?”

Another is what happens if you stop practicing, “It goes down,” Lazar said of volume measures. “But it doesn’t go down to zero,” it appears there is some residual benefit that lasts. “Once you learn something, you have it. But the calming, nonreactive effects kind of fade.”

What practice might work for you? The one you will actually stick with. “In exercise literature, it’s what you like that works for you. It’s probably true in yoga,” Streeter said. “You have to do something you like.”

“The Meditating Brain” was part of the Neuroscience and Society series, supported by AAAS and the Dana Foundation. Previous sessions include The Opioid Epidemic (story, video), How Video Games Affect Brain and Behavior (story, video), The Anxious Brain (story, video), Closing the Cognitive Skills Gap in Children (story, video), and Growing Older and Cognition (story, video). The article, which first appeared on the Dana Foundation website, is reprinted with kind permission of the author.

OTHER LINKS

Further information on Sara Lazar's work >

"Your Brain as Laboratory: The Science of Meditation" >

Mindfulness-based stress reduction >

NICKY PENTTILA is a writer, journalist, editor-of-all-trades, and Web wrangler for the Dana Foundation. In addition to reporting on brain science, she writes fiction, including the historical adventure The Spanish Patriot (2015). She lives in the Baltimore–Washington, DC corridor.

Add new comment