President Andrew Jackson and preacher Joseph Smith . . . "amongst the Indians." [o] [o]

2017. OBERLIN, OHIO. Planted along the perimeter of my gardens, the hostas define edges and establish boundaries. On one side, grass is to grow. The other side is reserved for a variety of plants, hand-picked by me. Originating in Asia and named for the Austrian botanist Nicolaus Thomas Host, hostas are prized by gardeners for their foliage rather than their flowers.

Hostas are benign sentries, allowing the grass to creep into my gardens, powerless to stop the slow meander of violets and lamb's ears. They can't even prevent their own children from creeping into the lawn to join the weeds growing there: the dandelions, the clover, the wild strawberries, hard as heartache and twice as bitter. More meticulous homeowners, I suppose, would drive these invaders away. My husband and I, involved in other projects, or perhaps just lazy, leave them alone. Besides, what are borders if not something against which to push?

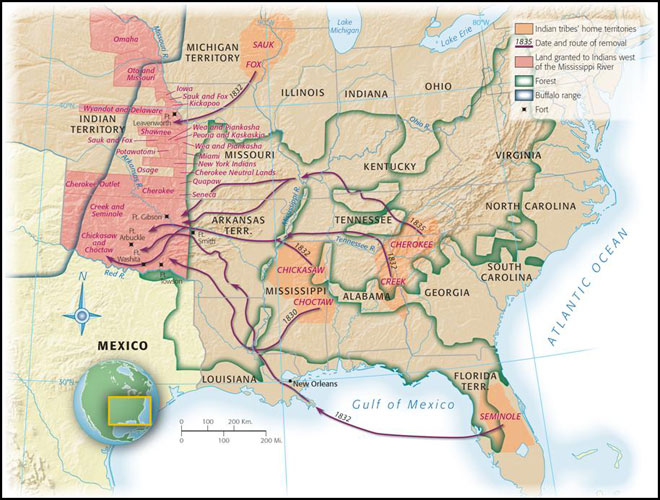

Giving up Indian Territory wasn't much of a sacrifice: this was a place no white wanted.

The hostas remind me of the Permanent Indian Frontier, an invisible line running north to south west of the Mississippi River. Established with the Non-Intercourse Act of 1834, the year Host died, the Permanent Indian Frontier served, in part, to divide Native Americans from white settlers. The eastern lands that formerly belonged to Native Americans were now owned by whites. To the Native Americans, Andrew Jackson forever promised the western lands: all of the United States' land west of the Mississippi with the exception of Missouri, Louisiana and Arkansas Territory. Indian Territory ran from modern-day Minnesota to Idaho and south to Oklahoma. Not included were Oregon Country, jointly owned with the British, and much of the southwest, owned at the time by Mexico. Despite its size, giving up Indian Territory wasn't much of a sacrifice for the United States: this was a place no white wanted. Believed to be part of a great desert, the land was considered useless for growing.

1869. LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND. Quickly, what are the most important parts of your life, can you name them? Those pieces you cling to? Those you pull out and hold to the light to find some meaning? What events have astonished you, standing out the way they do, like pricks of starlight, back when a carpet of stars was still visible at night, back when we could still see for lack of illumination?

Varieties of hostas. [o]

Come with me now. No need to pack. Bring nothing but your imagination. Follow the dreams of one family searching for a better life. I start with a child because it is she who first came to me; not in my dreams, but in the web of dreams and illusions we call the internet: Mary Elizabeth Speare, age 3. Her sister Ann Charlotte, 2. Their brother John Henry, forever eight months old, tucked into English soil before Mary was born. Their parents, Mary and Emanuel Ralph, two people irrevocably changed by the death of their son.

Like his father, Emanuel Ralph worked as a miller. But the grain chafed his skin, made him itchy in himself. He had dreams that the fifty-five acres his father farmed could not tame. It was 1869. The Civil War had ended. America was calling.

Before leaving England, the Speares had to rid themselves of possessions, splitting themselves again and again, growing ever smaller so they would fit the space allotted to them: ten cubic feet per person, a space two feet by one by five, into which they had to cram what was required by the British government. So many socks. So many shifts. A brush and a comb. They discarded what was unnecessary, shrinking in order to grow big again, in order to stand up and stretch in America.

Immigrants arriving in the New World, a continent made anew according to European conceptions. [o]

Likely the family waited a few days in Liverpool before they boarded the ship, sleeping in emigrant boarding houses, passing the time in astonishment at the city spread out before them, half a million people in one place when they were accustomed to nine thousand. There were endless shops: furniture and newspapers. Tobacco and candy. And the ticket office, too, of the Inman Line on Water Street, five guineas each for Emanuel Ralph and his wife, half that for the children to sail to the States. Perhaps they packed a bit of food for the journey, but not too much: daily rations were provided‒biscuits and peas. A gill of vinegar. Pork.

And suddenly the confusion and excitement of departure day. Through the emigrant hatch. Quickly now. Take what is handed as you move along. More government requirements, paid for by the immigrants. Dishes. Move along. Mattresses of straw. Move along. Six pounds of soap. Stand up and be counted before the journey begins.

Listen: ship manifests tell tales. Voices whisper from across an ocean of time. A grand steamer, the City of Paris, captained by a man named Henry Tibbits. Aboard this boat, Mary begins to shed one skin and exchange it for another.

Who am I?

This question is not yet birthed in Mary's mind, yet it exists as a concept somewhere. A dormant seed. Already she has learned she belongs in steerage, in the bowels of the boat, with 758 others, too much flesh pressed together, the odors of rot and sweat; vomit and human waste and lamp oil, sticky thick. And, too, the tantalizing scents of first and second class dinners wafting above like a promise.

Two people die on board, steerage passengers Henry Derricks and the infant Emily White, a small cross inked beside her name on the manifest. Watching the ocean guzzle the girl's body, ensconced in a bag and weighted with rocks, her parents never look at the Atlantic in the same way: The ocean is an escape. The ocean swallows dreams.

Eleven days after departure, the City of Paris arrived in New York. And the immigrants' straw mattresses were tossed overboard like so many dead bodies refusing to sink.

Get them so deeply indebted they'd be forced to sell their land. That was Jefferson.

2017. OBERLIN, OHIO. An old magnolia grows just off the sunroom of my house. The room isn't original: the house used to end at the living room. A previous owner added it on, enclosing a small porch and installing a bank of windows that looks out over the tree. They set down a pine floor; covered the chimney in a layer of white. Here and there, the paint has peeled away and, looking at the red bricks beneath, I get a glimpse of the way things used to be. Who added this room? I look through my book on Oberlin historic homes, turn to the page on my house. Was it Fiske? Dr. Morrison? Or was the addition more recent?

Four years ago, the year my family moved in, the magnolia sat in the middle of a grassy expanse outlined by hidden red bricks that had sunk beneath the soil. The following year, I decided to dig out the grass, to replace it with a garden. It's a big, circular bed, easily twenty-five feet in diameter. What else to plant but hostas, shade-lovers that will soon dominate the space I allot to them? Because hostas also do well as interior plants, as fillers, taking up vast spaces, like immigrants encouraged to fill up a nation.

1837. NEAR TUPELO, MISSISSIPPI. But what if the migration is not chosen, if not something the family has decided to do? What if a family is told to grab a few possessions and prepare to leave? What if there is no time to gather the things they need?

A different kind of leaving, then. One full of not only decisions, uncertainties and fears, but also packed with resentment and anger. But what else to do with the Native Americans?

Kill them all, as Jackson once proposed.

Get them so deeply indebted they'd be forced to sell their land. That was Jefferson.

Or remove them, like a stain or a cancer or a hat.

Cherokee: remove them.

Creek: remove them.

Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole: remove them, too.

John Gast, American Progress, 1872. Manifest Destiny: the idea that the US should expand to cover the continent; also a religious belief that the United

States should expand from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in the name of God.

Young Catherine McClure wakes, listening to the commotion outside the family's home, wondering for a moment at the noise until memory clicks in place: today is departure day. For years, Catherine's nation has been preparing for this journey, ceding their land bit by bit, looking for a suitable place to live. They purchased clothing, wagons and the equipment they'll need in their new home. Now, Catherine steps outside and watches the loading of the wagons. Tucked here and there are pots and pans and the blankets the family bought from the Europeans. This is a move the family has neither chosen nor embraced. They leave their homelands, the place their forebears have occupied for generations. They leave the bones of their ancestors. These are the Chickasaw, one of the last nations to leave its ancestral lands: millions of acres in Alabama and Kentucky. Tennessee and Mississippi. The Chickasaw watched and learned from other nations. They learned to negotiate. They had time to prepare. While their removal was less difficult than the removal of other nations, it wasn't any less heartbreaking.

A string of forts ran along the Permanent Indian Frontier. Soldiers were charged with keeping white settlers from invading Indian Territory and preventing Native American raids upon the whites. But the frontier wasn't writ in indelible ink, after all. What are boundaries except places to expand and grow? With the 1848 conclusion of the Mexican War, the United States acquired its southwest quarter. That same year, gold was discovered in California. Whites learned the Indian Territory wasn't a desert, after all, but fertile land. The Native Americans were again in the way . . . of prospectors' dreams . . . of the railroads . . . of cattle ranchers. The Permanent Indian Frontier was dissolved. The Native Americans were moved further west and south. The land given forever to the Native Americans was taken away.

1875. FORT SCOTT, KANSAS. This town was built upon the remains of Fort Scott, one of the forts along the Permanent Indian Frontier. Market Square, actually a diamond, houses restaurants and book stores, land agents and lawyers. By 1873, Mary Elizabeth Speare lives here, at the cement works where her father is an engineer. Sometimes, Mary steps from the house and watches the men push wheelbarrows full of stone up a track to the top of the kiln, twenty-eight feet high. She feels the heat of industry. She can see it wavering in the air like a warning, just above the kiln's ravenous mouth, fed twenty-four hours a day. The dust settles in the house. The constant noise of the stones, crushed and ground, grates upon her nerves. Perhaps she longs for a bit of silence to fill her days. Perhaps her father does too.

In the winter of 1838–39, the U.S. Army rounded up the Cherokees and forced them—at bayonet point—to move west. Four thousand of the malnourished Native Americans died on the freezing march to Oklahoma. This dark incident in American history is called the Trail of Tears. [o]

2017. OBERLIN, OHIO. Nearly all of the hostas in my beds—easily ninety-five percent—have come from my mother. Every spring, I drive forty miles to dig them up. Mom's hostas were acquired in the same manner, given to her by a friend when we moved to the farm and my mother was reshaping cornfields and woods into gardens. Now, I follow her as we walk the perimeter of a bed, once defined by a wooden fence, now outlined in rocks. She indicates the ones she wants to get rid of. The striped patriot crowds out the yellow loosestrife. The children of Empress Wu, a massive hosta, have crept into the driveway. "That one," Mom says, pointing. "And that."

While my mother hauls rocks to repair a driveway washout, I dig up the hostas and set them in a plastic bucket. I split the larger ones, driving the spade's tip through the center of the plant, severing the rhizome into two or four or eight parts. We break for a quick lunch before I head home. I need to resettle the hostas quickly. This is when the plants are most vulnerable.

1837. NEAR TUPELO, MISSISSIPPI. As they leave their homelands—some four thousand Chickasaws and their twelve hundred slaves—sounds echo in their wake: hoofbeats on the ground, the creaking of the wagons and the buggies, the voices of the drovers urging the oxen toward Memphis. They will cross via steamboat and overland. They will endure spoiled and insufficient rations. Some will get ill and some will die.

Who am I?

For now Catherine is unaware of the question. Already, perhaps, she has learned to hold contradiction in her heart. Although she doesn't yet look at it too closely, she knows she is suspended between two cultures: the white culture of her father and that of her Chickasaw mother's. White and red. Ubabeneli and God.

2017. OBERLIN, OHIO. I plant my hostas along the garden's perimeter. I group them beneath the magnolia. I place them with companions, dainty white coral bells next to blue-green foliage. A chain of red hearts bleeding beside green leaves edged in gilt.

The hostas will need a day or two to recover. To finger their roots cautiously into new soil. To settle in and thrive and begin again to grow. In late summer or early fall, they will bloom, dozens of purple flowers with six curling stamen on tall, tentative stalks. With first frost, the leaves will wither and darken. In the dead of winter, I forget about them there. With the first hints of spring, as the shoots shove their way through soil, I am suddenly reminded. ũ

END NOTE

When I was looking online for records on my historical house, I discovered a woman by the name of Mary Elizabeth Waite. Normally, a person's name wouldn't give me pause: this home has been owned by many people whose names are meaningless to me. But my mother, prior to her marriage, was also Mary Elizabeth Waite. As of yet, I have found no genetic link between the families. Nevertheless, after having spent so much time with the Mary who once owned this home, after telling her story endless times, after dragging my husband and children to Oklahoma, I consider her kin.

Mary is, of course, the child Mary Elizabeth Speare who came to the United States from England. She moved from Fort Scott with her family to the shrunken Indian Territory, modern-day Oklahoma. There, she met her future husband, Amos Richard Waite, son of Chickasaw Catherine McClure. Most of Catherine's children were educated at Oberlin College. Mary's children also attended Oberlin. And, in 1920, following her divorce from Amos, Mary returned to Oberlin with Winifred and bought my house from its first owner. And yet, in the book on my desk, Mary is unmentioned.

I've spent years researching this family, a family prominent in Oklahoma history but unknown, as far as I can tell, in Oberlin. Why do I search? Perhaps I do it to reassure the dead they are not forgotten, that their lives had purpose and value and meaning.

Perhaps I do it to reassure myself.

This article first appeared in the Journal of Wild Culture in June 4, 2017.

THE WILD CULTURE SCRIBBLER’S QUESTIONNAIRE — Kelly Garriott Waite

1. What is your first memory and what does it tell you about your life at that time and your life at this time?

I don't know if this is my first memory, but I do recall burying beneath a giant oak tree a dead robin I found. My grandmother was a true naturalist and a terrific bird-watcher. Over the course of about ten years, she kept a journal of every bird she saw each day. Whenever birds crashed into the windows of her house, she'd run outside and rescue them, warming them inside a shoebox so they could recover from the shock.

2. Can you name a handful of artists in your field, or other fields, who have influenced you — who come to mind immediately?

Wendell Berry, his essays, fiction and poetry; Mary Oliver, Annie Dillard, Anne Lamott, E. B. White, Erma Bombeck, John McPhee, Wallace Stegner.

3. Where did you grow up, and did that place and your experience of it help form your sense about place and the environment in general?

The first house I remember living in was situated on about three acres of land where we had a garden, a pond, and access to the Cuyahoga River. When I was eleven, we moved to a 40-acre plot of land and turned it into a farm. Both places — and my parents — taught me love of nature and the importance of self-sufficiency.

4. If you were going away on a very long journey and you could only take four books — one art book, one fiction or poetry, one non-fiction, one theory or criticism — what would they be?

I'm going to cheat and say I'd take all the Wendell Berry books on my shelves that I have yet to read.

5. What was your most keen interest between the ages of 10 and 12?

My brother was born when I was ten and we moved to the farm when I turned eleven. Those years were really exciting for me: helping care for an infant and helping turn cornfield and woods into a farm.

6. At what point did you discover your ability with your writing?

My grandparents were always reciting poetry to my siblings and me. So, when I was six, I thought I'd write my own book of poetry: pieces of pink paper stapled crookedly between two sheets of manila paper. There was definitely no ability there whatsoever: the "poems" are horrible, but that's probably when I discovered my interest in writing.

7. Do you have an ‘engine’ that drives your artistic practice, and if so, can you comment on it?

Definitely daily practice. Butt in chair with the internet off. I like to use old-fashioned journaling as my place to start thinking, or to get unstuck, then go to the computer once things get rolling. The most helpful thing I do is meet once a week with a writing partner who points out what's working and what's not.

8. If you were to meet a person who seriously wants to do work in your field — someone who admires and resonates with the type of work you do, and they clearly have real talent — and they asked you for some general advice, what would that be?

Turn off the television and the phone. Give yourself time to think and mull. Give time to the process. Keep a journal beside you at all times — often the best thoughts and ideas come to me when I'm washing the kitchen floor or making dinner. Finally, ignore the critics and those who tell you it can't be done.

9. Do you have a current question or preoccupation that you could share with us?

I'm currently researching my Polish great-grandfather and the history of the second owner of my historic house.

10. What does the term ‘wild culture’ mean to you?

Wild culture — to me this means creating community and definitely reliance on local initiative rather than government and/or business. It means gardening, a skill I haven't yet developed, but want to; my sister has a large organic garden at my family's farm and is able to feed her family for much of the year from her produce. That's wild culture for sure. Wild culture is connections. Foraging. Sharing resources. Independence.

11. If you would like to ask yourself a final question, what would it be?

[No answer.]

KELLY GARRIOTT WAITE is a writer currently researching the history of her 1908 house and the Native American woman who once owned it. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, The Globe and Mail, The Philadelphia Inquirer and elsewhere.

Add new comment