Body

Tamsyn Challenger’s latest exhibition, taking place at Beaconsfield in Kennington, South London, is entitled Monoculture, but it might just as well have been called The Homogeneity Tendency. Or perhaps the opposite: The Diversity Drive. Because the works being presented together under the title of Monoculture constitute not only an exploration of the worrying emergence of various strands of monoculture (in agriculture and online expressions of identity primarily) but also a tangible illustration of diversity running counter – the works themselves originating through sustained and wide-ranging research, then filtrated through all manner of media (performance, video, photography, installation, sculpture, even a small farm).

Monoculture is the result of Challenger’s nine-month residency at Beaconsfield, and extends the artist’s interests in the politicisation of (particularly female) identity. Specifically, the project stems from her experience of using social media to promote her previous project, the critically acclaimed and globally toured 400 Women. What Challenger observed was the apparently strict uniformity of online profile pictures – the narrow and restricted understanding of beauty engendered and endorsed by the internet. The masterstroke comes in understanding that this phenomenon is not unique to the world of social networking, but is in fact comparable to contemporary agricultural techniques, and their privileging of profitability over diversity.

The exhibition includes both ‘finished’ works and evidence of the creative process behind them. So downstairs in the café, for example, a wall-mounted flat-screen television is showing online clips of various lengths to set the scene for the kinds of ideas being addressed in the works themselves. A dying bee crawling in ungainly fashion across the lilac and burnt orange of an Aster’s petals marks the global significance of colony collapse disorder; a Columbian farmer outlines the difference between monoculture and permaculture; Noam Chomsky discusses the privatisation of the internet in 1995, “under circumstances that are still mysterious”; a news bulletin reports on Laguna Beach-based surgeon Dr Gregg Homer’s invention of colour-changing laser eye surgery. “The eyes are the windows to the soul,” he says, and clearly blue eyes equal open windows.

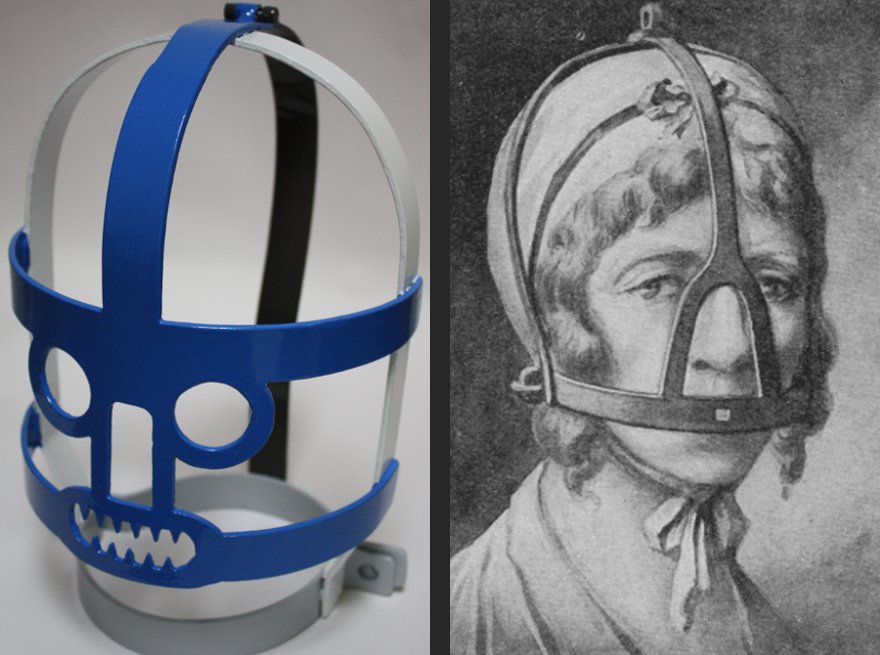

The central thread here is delimitation and its adverse effects. This is most obviously explored through a series of sculptures housed upstairs in Beaconsfield’s large exhibition space. That the gallery is housed in a former Ragged School feels appropriate – there’s perhaps something intrinsically constraining about educational institutions. The works themselves consist of a series of medieval-style devices for discipline, punishment and public humiliation: the stocks, a breaking wheel, a scold’s bridle (“the branks”), even a chastity belt suspended, swing-like, from the ceiling.

Constructed out of pine and fabricated steel, these tools of violent institutional oppression have been given a lick of household paint in the brand colours of social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter. Looking a bit like branded prototypes for some nightmarish new product line, they’re emblazoned with slogans like “Please love me” or “Do not exceed 140 characters”. The irony of branding such instruments with the colours of, say, Facebook (who claim their “mission” is to “make the world more open”) may be a smidge heavy-handed but the relationships between sexuality, repression and self-expression are forcefully observed nonetheless.

Elsewhere, a video plays of Challenger – with trademark whited face, round red cheeks and thick black hair – dancing a ritualistic jig with an accomplice in strange circular black costume. It’s shot on the banks of the Thames, but makes direct reference to the bizarre May-day ‘Obby ‘Oss festival that takes place each year in Padstow, Cornwall. Above the stairs, a television shows online profile images, whilst in the café, a series of similar images from an event earlier in the residency – a host of young women made up exactly like Challenger. “I’m a lonely little petunia in an onion patch”, sings Arthur Godfrey mock-mournfully in the background.

For me, these disparate elements converge most clearly in the dark space under the railway arches, where Challenger has constructed a small-scale farm. A walk-in permatunnel houses twin rows of grow-bags in which seedlings of oil seed rape thrust upwards out of rich black soil. It is this cash crop – or more specifically the neonicotinoid pesticides used upon it – that has been shown to be one of the primary causes behind colony collapse disorder, and while the European Food Safety Authority is moving to restrict their use, the UK’s coalition government is free to ignore their recommendations, and seems happy to do so.

In front and behind the semi-transparent tunnel are left-over props from further performances – a brightly painted ducking stool, a wooden Tamsyn Challenger mannequin propped up against a wall, a decapitated wooden head, and eleven silk zentai suits hanging from the brick ceiling, each one embroidered with the artist’s black, white and red features. Inside the tunnel and between the two rows of rapeseed is a small wooden dressing table with mirror. Cleansing wipes are strewn about on the floor, a black wig hangs above, and on the table itself a small outline sketch of the artist’s face – an exaggeratedly symmetrical, reductive version of it complete with dividing guidelines.

Here, amongst the plants and the UV darkness, this little sketch suggests that the constricting pressures of The Homogeneity Tendency are not restricted to capitalism or agriculture or medieval ritual or the internet. Rather, such a tendency is a central tenet of any ideology or discursive system. Fortunately, however, so too is the Diversity Drive. As Monoculture suggests, art itself has long been part of the process through which each age figures its ideal of beauty, and yet it is also through art – the proliferation of constructions, linkages, meanings, interpretations – that this narrow privileging can be both highlighted and undercut. There's always a kind of violence in the construction of identity, a violence that often involves art. But the horror of monoculture is that what is lost in the construction of a uniform ideal – bees, diversity, agency, dissent – are perhaps the very things that make such an ideal possible in the first place. Such violent sadness is what Challenger does so well to bring out.

Tamsyn Challenger - Monoculture is at Beaconsfield until 20th April 2013, and by appointment until the 24th.

beaconsfield.ltd.uk

www.tamsynchallenger.co.uk

For more information on monoculture and permaculture, read Liam's interview with Nigel McKean.

Image credits from top to bottom:

Tamsyn Challenger, Ducking Stool, 2013, pine, steel, household and polyurethane paints, found objects. From Monoculture (June 2012 – April 2013)

Image courtesy the artist and the project 'Let's Start a Pussy Riot'

Tamsyn Challenger, Selfie Brank 1 (Facebook), 2013, fabricated steel, household and polyurethane paints. From Monoculture (June 2012 – April 2013)

Image courtesy the artist and Beaconsfield

Tamsyn Challenger, Monoculture (June 2012 – April 2013), web-based research imagery

Tamsyn Challenger, Selfie Suit (residency image) 2012, coloured embroidery silk, zentai suit, lifesized. From Monoculture (June 2012 – April 2013)

Image courtesy the artist and Beaconsfield

Add new comment