There are many differences between bespoke clothing and mass-produced fashion, not least the altered relationship between the individual and a broader sense of signification. In the case of mass-produced, ready-to-wear fashion, the wearer is at best a curator – selecting a collage of materials already imbued with their own significance (as constructed via the processes of design, marketing, branding etc). In the case of bespoke, on the other hand, the wearer is intimately involved in the decision-making processes that go into the construction of the garment in question. As such, the bespoke item – couture ball-gown or military mess jacket or navvy cut brogue – contains far stronger traces of the individual's personality than any off-the-peg item could hope for. And these traces can linger long after the death of the individual.

It is this kind of territory, amongst others, being explored by contemporary artist Hormazd Narielwalla – not through the clothes themselves, but through the tailoring patterns that once underpinned their construction. Narielwalla has emerged as an artist of significance through his work with bespoke Savile Row tailoring patterns to produce collages that explore contemporary and historical ideas around pattern, gender and the repeat performance of identity.

After receiving his initial training in fashion – completing a BA in Fashion Design at the University of Wales in 2006 and an MA in Fashion Communication at the University of Westminster in 2007 – Narielwalla's interests began to shift towards those of a fine artist, albeit one whose practice is inextricably linked with the craft and creativity of fashion. He published his first book in 2008, had his first solo show at Paul Smith's Albemarle Street store in 2009, and recently featured at the Saatchi Gallery as part of the Craft Council's COLLECT fair in 2013.

His studio is strewn with papers and patterns, the paraphernalia of both the artist and the craftsman.

It was during a residency at famed military tailors Dege & Skinner, that this shift began to make itself felt. Narielwalla was fascinated by piles of military uniform patterns placed inside envelopes on the floor. With the individuals to whom the patterns referred no longer in a position to order new suits, they had outlived their purpose and were due to be shredded. “We don't really need them any more,” he was told. “They're dead.”

But Narielwalla saw things differently. He views these patterns – no longer tied to a straightforward use-function – as things of value in themselves. “It's strange,” he tells me during a visit to his London studio, “because people don't see the value in saving patterns until you turn them into 'art'. Yes, they were constructed to then make a garment, but as an artist I'm saying, 'this is the object, or even the subject; not merely a reflection or representation of something else.” This has clearly proved a fertile area of research, and Narielwalla is currently undertaking a PhD at London College of Fashion exploring these very ideas, with specific reference to the uniforms of the British Raj, as well as the importance of pattern in the visual arts more generally.

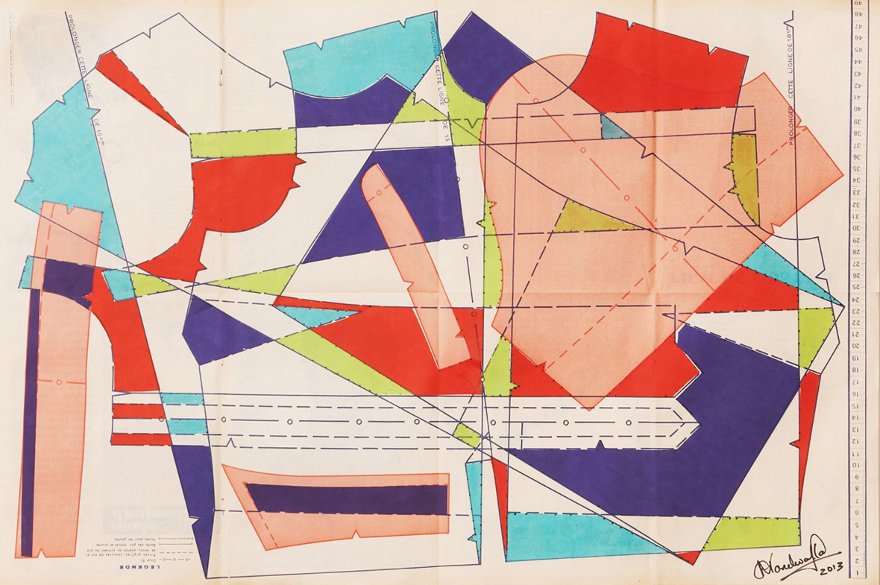

His studio, as you might expect, is strewn with papers and patterns, the paraphernalia of both the artist and the craftsman. A card 'Form-o-Matic' tailoring dummy perches high up on a shelf. Nearby, a Dege & Skinner carrier bag is stuffed full of materials – discarded by one practice but forming the basis of another. At the time I visit, Narielwalla is working on a series entitled Le Petit Echo de la Mode, which sees the artist reworking old sewing patterns taken from a long-running Parisian women's fashion magazine of the same name. For the sake of saving space in the magazine, each sheet is overlayed with a whole range of different patterns – differentiated from each other through variations in the style of line – and annotated with technical terms such as point d'ombre and passe de plat, reminiscent, it seems to me, of ballet, or even fencing.

Such recontextualising suggests that broader patterns of behaviour are also worthy of study.

Narielwalla then overlays these patterns with coloured acetate in order to suggest female forms – fractured or distorted in a manner akin to Cubism or Matisse. What's interesting here, I think, is that although the ensuing garments would have been hand-made, the patterns here are mass-produced, and evoke in their namelessness a generic ''woman of an era'. This is in stark contrast to the handwritten, personally attributable menswear patterns of Savile Row. This is something subtly reinforced by an earlier series of Narielwalla's – entitled Love-Nest. For this solo show at Margaret Street Gallery in early 2013, the artist produced gently humorous collages of male and female genitalia out of tailoring patterns. Having never seen a vagina in the flesh, Narielwalla admits that these were much more abstract and generic – influenced by the likes of Georgia O’Keeffe rather than personal experience. “Commercially,” Narielwalla notes with amusement, “the vaginas were much more successful.”

At the risk of overstatement, perhaps there is a wider point to be made here about identity, with specific reference to gender and sexuality. Identity, we know, is a performance. Whilst fashion has traditionally emphasised the external-facing theatricality of performance, it's a term that also encompasses repetition more generally, and the patterning of behaviour according to certain forms that prefigure or overrun the control of the individual. Narielwalla's recontextualising of patterns from bespoke tailoring and fashion media perhaps suggests, by synecdoche, that broader patterns of identity and behaviour are themselves worthy of study, and that the agency of the individual – customer or reader or artist or none of these – must operate both within and against pre-determined templates: not only fitting in but also loosening the threads, and spilling over the edge.

narielwalla.com

@narielwalla

www.saatchionline.com/profiles/portfolio/id/154441

Image credits, from top: Hormazd Narielwalla in his studio, photo © Tori Khambhaita; Hormazd Narielwalla, Le Petit Echo de la Mode No.17, photo © Denis Laner

Add new comment