Gathering up the pieces . . . a Koala bear surveys its neighborhood turned to rubble. [o]

WHITNEY SMITH Let’s begin with the long view of history. Today is November 15, ten days after the 2024 US election, the kind of election that has happened before, in different times, in different garb. I'd like you to address that statement, but also to help us get a grip on what's going on here, and help us see the less-than-benign underground tubers from which this event emerged. How do we begin?

HENRY GIROUX One thing that we need to realize is that if you can't learn from history, you go beyond the cliché of simply repeating it; you find yourself in a place of danger in which historical consciousness and its relevance turns to historical amnesia. The United States—and though I now live and work in Canada now, I speak of it as my country because I was born there—the United States suffers greatly from historical amnesia. One of the ways in which we can make it clear, or one of the ways in which it becomes evident, is not only that we've seen this in the past, whether it's in Pinochet's regime in Chile or in Nazi Germany or in Mussolini’s Italy, but the fact that it appears in a void in which people can't draw conclusions about what they see in terms of where the country might go and what that means. This is the first issue.

The free market was the template for all of social life, not just for the economy.

The second issue that seems to me to be crucial is that Trump may represent, not an exception, in light of our failure to examine history, he may, in some sense, represent who we are, what we've become, that we've never really, truly grappled with these ghosts in the past, whether we're talking about the elimination of indigenous people, or about slavery, whether we're talking about systemic racism, Jim Crow, the internment of Japanese people during the Second World War, and the unbelievable racism that infects almost every aspect of society. American exceptionalism has a way of blinding us to what we have to learn about the past in order to not repeat it, of course.

So, this question of history, as you're suggesting it, is really crucial, and, in many ways is a fundamental reason why Trump was re-elected—the exceptionalism, the historical amnesia, and, of course, in many ways, the failure of civic literacy and civic education have all contributed to this. So, it's not just a matter of history repeating itself, it's a matter of history being denied; and the consequence of that, in my estimation, is the emergence of not just the breakdown of American democracy, but the emergence of an upgraded form of fascism.

SMITH One of the relatively recent episodes in history that we are aware of, and which younger people are becoming more aware of, is Nazi Germany and the 1930s and what happened so that in 1932 Hitler received 37% of the popular vote. What is it that we can see there that helps us to understand this situation?

GIROUX There are a couple of things that we can see and a couple of things that we need to learn from. First of all, there was the assumption at that time that, basically, Hitler was a clown and could be controlled, and he had a lot of enablers, whether it be the Social Democratic Party or others, people of the corporate elite, who didn't take him seriously. And in many ways, certainly Trump in 2016 fit into the same mold, he was seen as a joke, he came from the world of reality TV, the entertainment world, and we could control him. And what we've realized is that while there were some guardrails that were put into place in his own administration that were able to control him somewhat, that's not going to happen this time.

The second thing about Nazi Germany and about Hitler and his enablers is the role the press has played in this, and particularly in this election. You had mentioned earlier, before we started, that you haven’t read the New York Times for a while. I’m assuming, in part, because it’s so hard to read it, because of what's going on. But the other part is that the mainstream press normalized Trump. I don't want to underplay the power of the right-wing media, which, as Michael Tomasky has argued, overcame the mainstream media and which he believes is the single most important factor in electing Trump this time. But the mainstream media normalized him. For example, a program like 60 Minutes interviewed Marjorie Taylor Greene and normalized this really fascist idiot, as if she's somebody that should be listened to, or the media not saying that the election was between the fight for democracy and fascism, but rather saying it was between two candidates with different views, which is really nonsense.

The third thing that we need to consider is that everybody believes that when you have fascism, it's because a government is overthrown by the military. But fascist governments are now being voted in, and we have to ask ourselves, what can we learn from history, particularly around Hitler's appointments? Well, it was all about the spectacle. It was all about the media. It was all about mobilizing ideas. It was all about appealing to scapegoats. It was all about resurrecting a notion of what's normal within the confines of a white supremacist discourse, and we are watching that happen again this time.

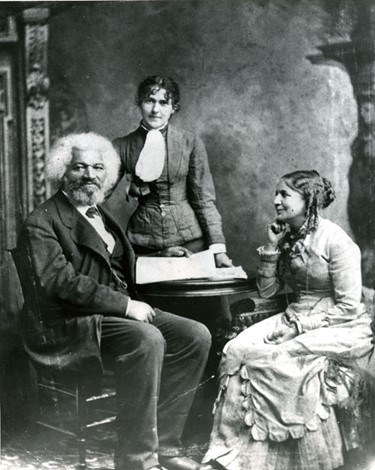

An escaped slave who became a leading abolitionist, orator, and writer, Frederick Douglass advocated for the end of slavery and for civil rights for African Americans. From left to right, Frederick Douglass, Eva Pitts, Helen Pitts, later Douglass' second wife. [o]

SMITH So the inclination toward fascism was a covert aspect of American politics in the last few decades is something we're beginning to understand. But now we're seeing it more clearly in people who are, as you say, denying history. What is it that Donald Trump is offering that these people are responding to?

GIROUX It's a great question, and it gets at the heart of what we're seeing in American history right now. First of all, you have a Democratic Party that completely ignored the working class. Somehow, from Reagan on, the Democratic Party brought in this notion that they wouldn't align with the Reagan's of the world, but they would align with the global financial elite. So, for instance, Goldman Sachs became a driving force. Neoliberalism from the 1980s on created a mindset that was not just simply an economic system that was horrendous and produced massive and staggering levels of inequality and concentrations of power, but that was also an educational force. And as an educational force, one of the things that it constantly stressed was that the free market was the template for all of social life, not just for the economy. Self-interest was the driving motivation to separate economic activities from social causes. That's about the death of morality. And I think in some fundamental way, it produced massive degrees of misery and alienation among the working class.

Thirdly, democracy started to become impotent as a term. It no longer had the attraction that it should have in a country that literally claims it's the most democratic country in the world, because it wasn't working. The people who made a claim to democracy were basically the same people who supported the bankers in the financial crisis of 2008. Well, thousands of people, millions of people lost their houses, lost their jobs. And so, you have the breakdown of the democratic ethos, you have massive suffering produced by neoliberalism, you have a terrible amount of loneliness and alienation in the country. Some people charted the deaths of middle-class people by suicide, which were rising precipitously, according to a couple of Princeton academics, and this need for community was mobilized very easily by Trump and his cohorts. The middle and working classes were mobilized around the notion of white replacement theory. It was mobilized around the notion that whiteness is special, and it's under siege. It's a site of bereavement, and we have to do everything we can to protect ourselves, to get our jobs back. And there's one way of doing that, which is to blame blacks, to blame immigrants, to blame women, and to blame all those populations considered utterly disposable. Increasingly what that did was it produced a class of people, a group of people who, rather than hide the kinds of crimes and the language that we saw in the 1930s, took those expressions on as a mark of distinction. There was a bold denouncement of others, I mean, nothing was hidden.

I’m thinking a lot about what Trump is claiming he's going to do immediately with immigrants, claiming that he is going to depot 15 to 20 million. And I don't think they have the money, and I don't think they have the tools to do that immediately, but I’ll say this, there's an image that comes to my mind. When I think of these people being rounded up, put in buses, put on trains, put in all kinds of modes of travel, I think of the camps, and I think of Jews being put in boxcars. What are we going to see? Are we going to see trains passing through every country, in every state in the United States, filled with children, filled with brown people, filled with immigrants, on their way to where? To be exterminated? To be put in concentration camps? To be put in holding centers in a state that Trump claims is going to massively expand the carceral state? What we did see in Germany, as the punishing state rose, was the decline of the social state, and that's exactly what we're seeing here. That's exactly what's being promised.

Jane Addams was a pioneer in social work and the settlement house movement and a leader in women’s suffrage and world peace. [o]

SMITH Looking back at the 1930s in Germany and the Eichmann trials in the 1960s, and Hannah Arendt's take on it, we almost automatically ask: "How could this happen? How could this be allowed to happen?"

GIROUX The left failed around this issue. The question was never raised as to how a population's public consciousness could have been produced and engineered in ways in which they would accept a culture of cruelty, a culture of abuse, a culture of white supremacy and white nationalism. As Stephen Miller said, quite obviously and in a very upfront way in Madison Square Garden, not too long ago, “America is for Americans.” Hitler said, “Germany is for Germans.” What I’m getting at here is that the crisis that we have faced since the 1980s — economically, historically, politically, but most important, educationally — has not been matched by a crisis of consciousness. We have ignored, ever since the Powell memo of the 1970s ["Confidential Memorandum: Attack on American Free Enterprise System," penned for the Chairman of the Education Committee of the US Chamber of Commerce, by lawyer Lewis Powell, that called for American businesses to defend their interests in the face of liberal concessions, through the creation of lobby groups, media and think tanks], how crucial education has become with respect to being central to politics. And, how it was shaping a mass consciousness that was becoming more comfortable with white supremacy, with racial cleansing, with hatred, with bigotry, systemic racism, the hatred of women, the elimination of civil rights, and the destruction of the guardrails that keep democracy alive.

SMITH Again, this is more an educational issue than it is anything else.

GIROUX I am very much saying that. This is a massive failure, and what it fails to recognize is that with this collapse of civic literacy is something that we should know, and that is that domination operates not only through economic structures, but also operates through beliefs and forms of persuasion, and we have to ask ourselves where did this, and this is my term, pedagogical terrorism, come from? It came not so simply from an attack on public and higher education, it came from some of the most powerful educational and cultural forces that we have ever seen, whether we're talking about Fox News, or we're talking about the social media, or we're talking about the far-right press, media system. They control the discourse, they control a right-wing discourse, and the mainstream press normalizes it by refusing to name it for what it is. And that is where we failed enormously. And we also failed to appeal to working-class people. I mean, you're not going to have reform in this country without a multiracial, multi-class movement, it's not going to happen.

SMITH So let's go back to the point when you think a change happened, let's say at some time after Second World War, when the quality of education diminished, or when the opportunity to have education that served society was reduced. What could have been done at that juncture that was not done; or, how was policy or whatever was manipulated to the point where it was not important? Was that conscious or unconscious or was it just a result of all these other things happening?

GIROUX It was always conscious. Milton Friedman famously argued that businesses had no obligation to take on any form of social responsibility beyond maximizing profits for their shareholders. This perspective reflects a broader, deliberate effort to undermine the critical functions of education and dissent—posing a threat to the corporate claim to a value-free neutrality. During the McCarthy era of the 1950s, this strategy was explicit: labelling educational institutions as hotbeds of communism or Marxism served to discredit them, even though such accusations were largely unfounded. By the 1960s, the landscape began to shift. The social revolutions of that era—civil rights, student movements, and calls for greater equality—alarmed conservatives. These movements challenged entrenched hierarchies, and institutions like higher education and public schools became democratizing forces, offering opportunities to historically excluded groups, including nonwhite communities. Key milestones like Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which ruled segregation in public schools unconstitutional, further fuelled conservative fears. In response, figures like Ronald Reagan gave voice to a reactionary ideology that framed government as an impediment to individual freedom and economic progress. Reagan amplified the idea that schools, like businesses, had no role in promoting social responsibility. Echoing Milton Friedman's ideas, this view held that education should focus solely on preparing students for the workforce, stripping it of any mission to cultivate informed, critical citizens. Under this framework, government responsibility shifted away from ensuring equity and justice and toward deregulating corporate interests, further entrenching a system where the public good was subordinated to market imperatives.

Now, when I was younger, the debate in the ‘60s and ‘70s was about whether schools were democratic institutions or simply places that trained people for the workplace. Now, we finally arrived at the end point, where people are censoring education, like DeSantis in Florida and a number of right-wing governors who now have even greater power, as does Trump, and a vice president who says that professors are the enemy. And, of course, all of us who have a critical function in education, we're Marxist vermin, and whatever else they want to call us. But I think now what we have is not whether schools are for democracy or whether schools are for the workplace, now they're indoctrination centers, now they ban books, now they reconstruct history to eliminate those aspects of history that need to be learned so that they will never be repeated. Now they tell professors that if they talk about anything, from abortion rights to women's rights to slavery, they can be fired. So, we have seen the end point of this endless attempt to strip education of its critical and ethical functions.

Now, to go back to your German analogy, the Nazi analogy, that's exactly what happened in Hitler’s Nazi Germany, it's exactly what happened in Pinochet's Chile. I mean, in Chile, professors were taken up in helicopters and thrown off into the woods somewhere or tortured. The first group, the first enemy of authoritarianism, comprises the scholars and journalists that challenge rising authoritarianism, but we need to extend that to the institutions that would challenge it. And that's the state we're in today.

A sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist, W.E.B duBois (1868-1963) co-founded the NAACP and the first-ever Pan-African Congress in 1919, organized to demand freedom for colonized African countries and a greater voice for Africans worldwide. [o]

SMITH You've spoken about education. I have a sense that you have thought a lot about how the United States is, in some ways, very different and very similar to China — in that the dark seeds of the Civil War, like China's Cultural Revolution, is still present in the minds of many Americans.

GIROUX I’d say, historically, the thing that marks the United States in a way that is unique, and certainly was interesting to the Nazis, because they tried to find out as much as they could about it, was basically systemic racism. Systemic racism has shaped this country from the day it was born, and while we don't want to underplay the question of economic inequality around matters of class and women's rights, racism has been a polluting influence that has touched almost every election we have seen, particularly since the 1970s. And it’s the ghost in the closet, and what Trump did was to unleash it—he made it visible, he made it a badge of honor.

The other thing is that this is a country that has diminished the welfare state in the name of its own exceptionalism to a degree that is breathtaking. For example, this is the only advanced country in the world that doesn't have national health insurance. Right? We know what that means. And, I guess, what I’m really getting at is, if you want to talk about democracy outside of simply empty verbiage, you have to talk about the fact that you can't have just political rights and individual rights, you must have economic rights, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt said. If you live under a bridge or you're choosing between food and medicine, you don’t care much about voting, you don’t care about belonging to a church or a synagogue, you don't have time to care about that, because poverty is such a deprivation that it depoliticizes people. One of the things that I find, in looking at the history of this country, is the merging of three things: the vast machinery of depoliticization that has prevented people from voting or having any sense of agency, the historical amnesia that normalizes that, and a political economic system that ironically defines itself as a democracy when money drives the system, and the people who drive the system are the financial elite, people like Elon Musk. I mean, he was allowed on a phone call recently along with the coming President to talk to Zelensky. Who is this guy? What right does he have, a non-elected billionaire, to be able to shape American policy, jump up and down on a stage with his stomach showing, produce all kinds of nonsense over the website that he now owns? How can we call this place a democracy? You can't have a democracy when four families own as much as the bottom 50% of the population. That's not a democracy. That's an autocracy. And now what we're moving to is an outright fascist politics built on the notion of racial cleansing. That that's the term I want to use, and I want to elevate it and expand it to say it's now moved away from simply systemic racism into white nationalism. So that it's not just Blacks and brown people who are immigrants, rather, if you're not a White Christian nationalist, you don't qualify as an American citizen. So, this is a very dangerous moment in American history around the range of exclusions that are being systematically legitimized and which hopefully will not be implemented.

SMITH If we look at the popular vote, we know that the people who voted for Trump were not just white people, they were also Latinos and Blacks and Asians.

GIROUX Look, 70% of blacks voted for Kamala Harris. I’m not sure what the exact figure was for Latinos, but certainly more voted for Harris than they did for Trump. But I don't think that your biology, your nationality, the ethnicity you occupy guarantees anything. You know, that strikes me as silly, to say, if you're Black, then you have to be progressive; if you're working class, you have to be progressive. What that eliminates is the way in which people can internalize certain notions of ugly freedoms, or certain notions of identity and misbelief that, in some ways, surrendering their own agency to a strong man authoritarian will provide them with whatever they're looking for that will make their life better. I don't see these people as stupid—the notion that they're “deplorables” coming from Hillary Clinton is simply a form of shaming. What I want to understand are the complicated factors that drive people to vote for leaders against their own legitimate interest. That's what we have to look at. That's about culture. That's about power. That's about education.

I mean, we had people of color in the Bush administration who were warmongers. Color doesn't care; we have a Supreme Court Justice who is an outright unadulterated racist and authoritarian. The color doesn't matter, unless that experience is mediated through a theoretical or conceptual framework that allows people to basically understand both who they are, what their relationship is to others in the larger world in a critical and attentive way, that they're as susceptible as anybody else to authoritarian impulses.

Eugene V. Debs (1855-1926), a labor leader and five-time Socialist Party candidate for US President, he advocated for workers’ rights and social justice. Bernie Sanders, a contemporary politician known for his advocacy of democratic socialism and progressive policies on healthcare, education, and income inequality.

SMITH Let’s say there is a Black or Latino person who is aware of Trump’s racist rhetoric, yet there are other issues that allow them to dismiss it.

GIROUX You can say the same thing about white working-class people who know that at some level Trump is a union buster and a scab, and he's speaking in their interest and he believes it. Yet, many of them voted for him out of a racial panic, that is, they bought the notion that their economic precarity is the result of allowing immigrants to take their jobs. And I think the question we have to ask ourselves is, what are the modes of persuasion, and what are the pedagogical interventions, and what are the cultural apparatuses, and what are the larger institutions that basically produce this kind of civic illiteracy and racist ideology. Paulo Freire dealt with this in Brazil. In the 1960s, peasants would sit back initially and say, “We're stupid.” They bought a notion of cultural domination, of unfreedom that defines their interest, because the forces that bear down on them are almost overwhelming.

SMITH There's a sophistication of the Republican Party or the right wing that is astounding, and you've talked a bit about it, Trump's understanding of it and his ability to execute it. It has been said that with Richard Nixon, the Republican Party was not about policy suggestions or selling policy, it was about this cultural targeting that you're talking about. Can you speak about that

GIROUX Well, I’m not sure it wasn't about policy. I think that power always operates in the interest of policy. The real issues are how to legitimate your actions and how to normalize the practices that you're going to use to basically gain power. Nixon was a racist, Bush was a racist, and Reagan was a racist—they all used racial tropes, from the welfare queen to whatever, to basically divide people against each other along racial and class lines. I mean, that's endemic to American politics, it's part of what this country is, and it's one of the reasons it elected Trump. So, I don't see anything unusual about that, except that it's never been dealt with historically and politically enough in a subconscious way to really recognize that what America has become is not unlike what Donald Trump is, and that is a country that basically has a long legacy of racism, extermination, bigotry, and misinformation.

SMITH There's a writer who agreed with what you're saying, and he used the example of William Faulkner talking about his local domain, Yoknapatawpha county in Mississippi, in which people are often mean, selfish and greedy and do not hold the values that Tim Walz and Kamala Harris were standing up for and proclaiming.

What we can't ignore is that it doesn't begin only in Nazi Germany, it begins with the Ku Klux Klan.

GIROUX We're in a dark moment, and just because there are certain traditions in American history that are deplorable doesn't mean that is all that we are. We can't all be defined simply by the politics of domination and exploitation and greed. We did have a civil rights movement, we did have a Civil War to preserve the union, and we have had a youth movement that's enormously powerful and brave and so forth. We have had people who have sacrificed their lives in the interest of fighting for democracy. That's the other side. I mean, the other side is you have a country that's basically vying over a very fundamental question, which my friend Eddie Glaude Jr. has raised a number of times, even on MSNBC. He points out that there is a real distinction here between the promise of America and the reality of America.

But the promise of America is not simply defined or subverted by these right-wing goons or these emerging fascists, or the corporate elite. Beneath all of that, there really is union resistance and worker resistance, and the students are losing jobs and being thrown out and being beaten. That's the tradition that I want to focus on, but I don't want to focus on it in a Pollyannaish way. I want to focus on it in a way that connects it to both history and to a larger set of forces that are attempting to suppress it. And I think that we have to ask ourselves both what are the forces that put it under siege, and where are the possibilities we can go back to what it means to fight for a real democracy, rather than legitimate a fascist who outrightly hates democracy and all that it represents.

SMITH Regarding the state of the left in the US today, how do we understand the weakness, brokenness, dysfunction, political incontinence—however we need to describe it—of progressives at this time. Secondly, what needs to happen to take it out of its current condition?

GIROUX It’s a very important question. First of all, the left needs to unite the various silos that it occupies, and come together under a mass movement, a multiracial, multiclass movement in the name of radical democracy. They need to both unify and to have an umbrella. You can be for women's rights; you can be against racism and still hate women and be a misogynist. You can be a feminist and basically still employ a racist consciousness. I mean, we have to talk about the fullness of democracy, and how all these movements have to come together in ways that present a notion of democracy in which injustice, exploitation, and suppression of racial, economic, cultural, and political rights is simply not tolerated and has to be made visible.

Second, it seems to me we need a new language. I mean, we need to think through what I call a language organized around a politics of identification. And what that means is we need to talk to people in ways in which they both understand what we're saying and can recognize themselves in the language. In other words, we need to be contextual, we need to be local. You know, we need to understand people's lives, their stories, who they are, what they want, and learn from them, and have them learn from us.

Third, there needs to be a massive educational movement in this country, in which literacy, civic and otherwise, is directly linked to the fight and the struggle for democracy.

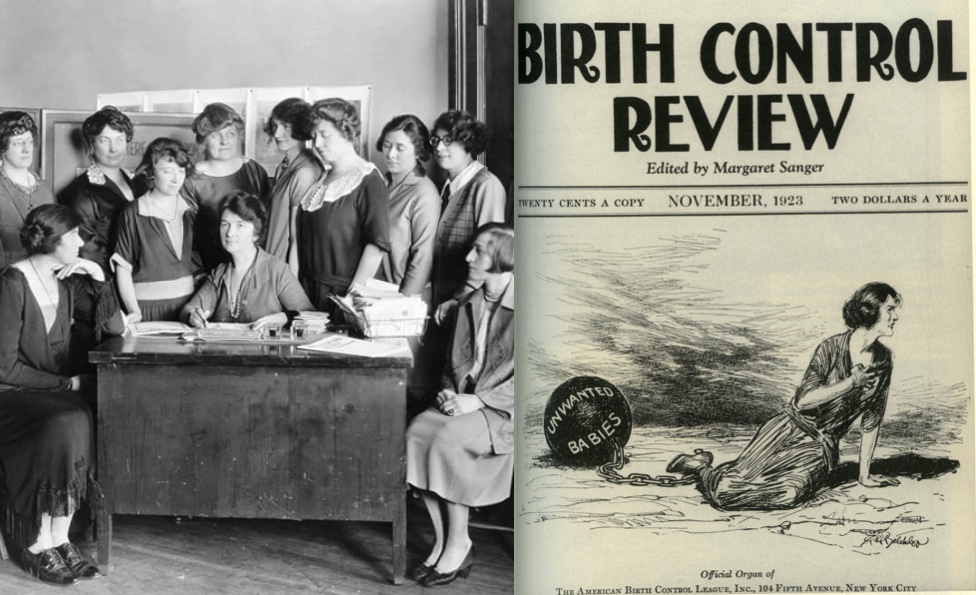

Margaret Sanger (1879-1966), an activist who opened the first birth control clinic in the U.S. and founded organizations that evolved into Planned Parenthood.

Fourth, we have to mobilize young people to be cultural producers and not just cultural critics. I’m older than you are, but our generation grew up in a print culture, whereas this new generation is informed by social media. My students know everything about social media, and they have skills to basically break through these massive disinformation machines that have utterly depoliticized people and sold them an ideology that is nothing but the swindle of fulfillment. They can do this. I have a lot of faith in young people, they're border-crossers, they're interdisciplinary, they talk to young people in other countries, they know how to use the media; and it seems to me, while they have been written out of the script of democracy in the past, they are really being written out of the script of democracy now, and they're going to face a series of issues—from climate change to racism to the destruction of higher and public education—unlike any generation that has come along. This is the most massive political, economic, educational, historical crisis since the civil war. That's the state we're in now. And all you have to do is listen to the language of the Trump administration and look at the people who are being appointed to it and look at what they will do once they're in power. This isn't ambiguous. There's nothing ambiguous about this, you know.

SMITH You spoke earlier about the impotence of the term democracy, and, of course, Ivan Illich talked about “amoeba words.” For example, Shell Oil can say, “We are a ‘community,’” and that’s an amoeba word that loses meaning when a corporation tries to describe itself as a local, neighborly entity. Let's look at this term fascism. It’s thrown around so much, but I’d like to look at the fine grain of it, and what we're talking about when we use that word.

GIROUX I think that when we talk about fascism, one of the things that we have to recognize and take seriously is what people like Hannah Arendt, Sinclair Lewis, a number of other people, theorists who have been attacking this subject since the 1930s, and that is: fascism is not something that's simply interred in history, it's an historical relic. You can't say, well, we don't have concentration camps, so therefore we don't have fascism. What Primo Levi and a number of other people have said is that fascism exists in different forms, and the seeds of it can be found in every country. We have to begin to understand what the mobilizing passions of fascism actually look like.

One of the things that becomes clear is that they look appear to be racial, and that the question of racial supremacy and racial cleansing is pretty obvious, which, first and foremost, strikes me as an element of fascism that we really can't ignore: that it doesn't begin only in Nazi Germany, it begins with the Ku Klux Klan. Secondly, you begin with the elimination ethic that some people aren't worthy and need to go. You look at the anti-intellectualism. You look at the crushing of dissent. You look at the militarization of everyday society. You look at the call of the strongman. You look at what we might call the notion of the culture of fear, the fake communities. You look at the stoking of anger. You look at a language that says you have enemies—that the country is divided into enemies and those who basically are saviors. I mean, all of these elements add up to and, in some way, imitate a kind of fascist logic.

Now, the way that fascists express themselves in different countries are different. In the United States, they express themselves in patriotism, and the American flag, they express themselves in the need, in some way, to give up democracy, because it's failed. They advocate for a democracy in which citizenship is now abruptly redefined in terms of massive levels of exclusion. Even some of the more prominent historians who have denied that Trump was a fascist and that fascism was emerging, are now saying, in effect, that January 6 basically convinced them that fascism is really on the rise in the United States.

I use a term that a lot of people don't like, and I think I’m right on this, it’s the term neoliberal fascism. And I think that what I’m basically saying is that neoliberalism failed, and it could no longer legitimate itself. And this type of this economic model and its own failure turned to authoritarianism, and particularly to the attributes of people like Trump, these emerging neo-fascists. Rather than saying we're going to offer you social mobility, we're going to create more jobs, we're going to lessen inequality, everybody's going to rise up—that all died with the financial crisis of 2008. So now, what do they say? They say immigrants are the problem. Black people are a problem. The homeless are a problem. Dissenting young people are a problem. The communists and the universities, they're the problem. These are all elements that come right out of the fascist playbook. They just take a different form, and sometimes they arise in a different language.

But I think the claim that fascism is only an historical relic, it's not only wrong, but it also means you can't learn from history, it means you can't understand the nuances, you can't understand the way in which certain elements of fascism in the past that were not as strong now are strong. No, we don't have concentration camps. We just have a carceral state in which 5% of the population is in prison. So, we need to be careful with the refusal to acknowledge that.

Cesar Chavez (1927-1993), labor leader and civil rights activist, speaks to members of the United Farm Workers during a rally in the Imperial Valley, 1979. The UFW was staging a lettuce growers strike. [o]

SMITH Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize–winning economist, has just published a book called The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society, where he examines how free markets have contributed to inequalities and environmental crises; the title plays off Hayek's influential The Road to Serfdom from the 1940s. Stiglitz argues for re-imagining of social, economic and legal systems as a way of fostering progress for everyone., and he uses one example of freedom as the case of a person who is impoverished or racially stigmatized and how such a person does not have freedom because of their situation.

GIROUX We've been fed a myth around freedom, and that we so limit the notion of freedom that we individualize it and simply say that it's basically more powerful when it's simply organized around freedom of self-interest, you know, the freedom not to be bothered. And I think that we failed to distinguish between something really fundamental in a highly iniquitous, unequal society, in that we don't talk about the relationship between choice and constraints. And it seems to me that these ugly freedoms that the right advocates, individualizes freedom in a way to suggest that if you don't have the freedoms that some people have, generally the ruling classes and the elites, then you—it's a matter of character, you haven't tried hard enough. If you're homeless, it might be because you like to be outdoors. If you're unemployed, it's because you're too lazy to look for a job. And I think that what gets articulated is a notion of freedom in which the political collapses into the private, and that we are unable to translate private troubles around the lack of freedoms into larger systemic considerations.

That's an enormously powerful legitimating ideology that has just trapped those Blacks on the right, the Latinos on the right who buy into that, who look around and say, oh, wow, yeah, there are other Latinos or Blacks here who are really a threat because they don't try hard enough, they have a defective character. This is the utter privatization and deep politicization of politics. And in some ways, it's an attempt to collapse the language of the public into a therapeutic language. But in the end, it's not therapeutic. In the end, it's very damaging, because in the end, all problems become individual problems, and there are no such things as systemic problems. And that's where the notion of freedom gets utterly destroyed and becomes a tool for legitimating authoritarianism, because it then capitalizes on fear. Freedom becomes about fear, providing security. It's not the freedom to prevent poverty. It's not the freedom to, in some way, eliminate inequality. It's the freedom to protect themselves against a whole range of threats, that people like Trump tell us about, for example, that group of immigrants is going to eat our pets and rape our wives in the suburbs.

SMITH Would you say that the left or the progressives, the palette that they are using is way too limited, or the wrong one, or they're just out of their depth, they need to go to a whole new place? You talked about a new language.

Can you comment on that?

GIROUX I don't want to underestimate the importance of the left in its various forms in this country or in any other country. I think they've made visible a range of oppressions that ordinarily have been hidden. In some cases, they've overthrown right wing governments, but the left in the United States is too limited in terms of an identity politics that is crucial—as in 'mocking out' certain forms of oppression—but does not seem to have the power of persuasion it needs to really be able to understand the specific forms of anxiety and exploitation that people in general feel. And I think they failed there massively. I think that we don't have enough public intellectuals in this country on the left who are speaking in a way that gives them both public access and offers a public language. We don't have intellectuals who, like Stanley Aronowitz, Angela Davis, and maybe Cornel West today, can speak to multiple audiences, who are power persuasive, and I think that too much of the left has been academicized. It's either been academicized or caught up in movements that are too limited, both in their appeal and in their ability to change consciousness.

SMITH To finish up, I’m going to ask you if you have a dream, and then imagine that we go forward 20 years and this dream works out in a way that really pleases you, and you can die happy. What would that dream be?

GIROUX My dream would be that democracy is now founded on anti-capitalism values, that profits don't drive the society we live in, that nobody has to suffer because of poverty or homelessness or lack of food, that everybody has an opportunity to have a good life; that personal rights and social rights are matched by economic rights, that we have a universal wage, that power is concentrated in the hands of people who have some control and learn how to govern and not simply be governed. My dream is to live in a country that really believes that the most important issue driving every institution is that no society is ever just enough, that the fight for justice never ends, and that democracy is so precious that we have to struggle for it and protect it all the time, and that we have to do it in a way that brings together joyous communities, as Martin Luther King said, beloved communities, and we have to do it in a way that the discourse of inclusion becomes inseparable from the discourse of equality and justice.

A marine biologist and conservationist, Rachel Carson (1906-1964) wrote the book Silent Spring that spurred the modern environmental movement.

SMITH Is there anything else you want to add?

GIROUX One thing . . . with respect to the age issue. You know, I am 81 years old and I often get letters, horrible letters, from people who read my work and then say, well, you're going to die soon, and we can't wait. I have asked myself, what drives these people? I mean, their future is based on a nation that punishes any criticism that makes power accountable, that challenges these fascist elements, anything that challenges the ultra-nationalism, the contempt for the rule of law, the anti-intellectualism, the language of racial purity and disposability, or a critical education. What is it that they identify with that elevates these caustic, horrible emotions over reason? One fellow sent me a picture of him standing next to his kid, a five-year-old, and he wrote things like, I can't wait for you to die, you have been such a terrible influence. And I think there's something really fundamental here about ideology, about the subconscious, about what it is people have internalized that turns them into a person who’s antithetical to democracy.

I have no wish to shame them, although I also have no interest in going to dinner at their house or meeting them in a bookstore, but I want to change the conditions that make these attitudes possible. So, if I think about the future, I want to think about conditions that produce the Martin Luther Kings, the Gandhis, that produce massive movements, that produce great filmmakers, great educators, great women, great men who struggle together in a way that is self-consciously benevolent and compassionate. That's what I want. I want to go to dinner at their house.

SMITH Henry, it’s been a pleasure.

GIROUX This is exactly what an interview should be. You don't want to hide behind the shallow questions that have nothing to do with anything. The questions make the interviews, not just the people responding. The questions are central, and you did a great job of that today.

SMITH Thanks very much.

GIROUX It’s great. It's invigorating. Thanks a lot. ≈ç

HENRY A. GIROUX currently holds the McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the English and Cultural Studies Department and is the Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy. His most recent books include The Terror of the Unforeseen (2019), On Critical Pedagogy, 2nd edition (2020); Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy: Education in a Time of Crisis (2021); Pedagogy of Resistance: Against Manufactured Ignorance (2022) and Insurrections: Education in the Age of Counter-Revolutionary Politics (2023), and coauthored with Anthony DiMaggio, Fascism on Trial: Education and the Possibility of Democracy (2025). He lives in Hamilton, Ontario.

Add new comment