From a few gathered together where needs and ideas ignite into a vision girded by faith . . . The Party, by Vladimir Makovsky (1875). [o]

We live in a revolutionary moment." — C. H.

Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt

by Chris Hedges

Nation Books (2015), 304 Pages

Chris Hedges is a gift to our times.

Born in Vermont, he grew up in rural upstate New York and graduated from Colgate University with a B.A. in English literature. Then on to Harvard Divinity School where, like his father, he became a Presbyterian minister. Men of the cloth don't often hurl themselves into war situations, but Hedges spent nearly two decades as a correspondent in Central America, Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans — 15 of those years at the New York Times — where he was constantly face-to-face with desperate human calamities and violent military confrontations. He contributed to The New York Times staff entry that received a 2002 Pulitzer Prize for coverage of global terrorism.

Hedges has written a number of books before Wages of Rebellion, including Empire of Illusion, War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning, and Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt (co-written with Joe Sacco) — all of which have become important contributions to radical political thought in North America and Europe.

I came to Hedges' offerings late as, having moved to Bolivia after Evo Morales' inauguration in 2006, I had focused primarily on the unfolding of Morales' Movimiento al Socialism government. But then Donald Trump won the White House — Don’t get me wrong: it's not that Hillary Clinton would have worked to make a better world, ¡por favor! — but I suddenly felt an overwhelming fervor to understand/feel/see what on earth was going on. For the first time in seven years, I traveled to the northern empire, and while there I felt another uprising of passion: to update my thinking by plunging into the writings of key radical authors I had managed to miss. At tea one day, friend and comrade in the 1980s anti-nuclear movement, Charlotte Cook, said, “Ah, and there's Chris Hedges. You have got to read Chris Hedges!”

So I did.

Wages of Rebellion presents a concoction of perspectives garnered from the history of human rebellion, Hedges' experience reporting from inside war zones, insights from economists, historians, and rebels on both the nature of the “beast” and the nature of resistance, all interwoven with themes explored in world literature.

His message reminds me of a clarion call I once heard — and obeyed — many years ago. It was bellowed in 1969 in Sproul Plaza at the University of California/Berkeley. Some 3000 supporters of People's Park had jammed the plaza. We — students, professors, street people, gardeners, carpenters, grandmothers, families, street people, store owners, musicians — had spontaneously created the park on vacant land, and the university had sent in law enforcement to crush our experiment via eight-foot tall cyclone fencing and heavily-armed police presence. The crowd in Sproul Plaza was champing at the bit when, from the podium, Student Body President Dan Siegel cried out “LET'S TAKE THE PARK!” And lo and behold! 3000 people marched three blocks down Telegraph Avenue to the fenced-off commons. We fought non-violently, using the force of our numbers and the agility of our feet, for two weeks straight, every single day — sometimes protecting ourselves from CS gas with wetted bandanas, sometimes with real gas masks; once enduring a mass bust and imprisonment of some 375 protestors; another time a helicopter bombing of toxic gas followed by beatings by the National Guard, and the use against us of shotguns and buckshot. All manner of city police from several cities, the Guard, the California Highway Patrol, and the fiercest of all — the Blue Meanies of the county sheriff's office — took up the battle, using tactics copied from those used in the U.S. military's anti-Viet Cong war.

But (to recall a phrase from the times), dig it: we won back the park for a good 40 years. In 2011 the university bulldozed the land hosting the communal garden while students were away for winter break.

That same clarion call that catalyzed so many in 1969 is echoed in Hedges' book. After devouring Wages of Rebellion, I emerge feeling the same rebel zeal I had as a young social science student at Berkeley.

Here's hoping you will too.

"America is ungovernable; those who served the revolution have plowed the sea." — Simon Bolivar (1830). The Uprising, by Diego Rivera (1931). 74 x 93 3/4" (188 x 238.1 cm) [o]

Excerpts from Wages of Rebellion

Revolutionary movements, nourished by radical new ideas and the collapse of bankrupt ruling ideologies, have throughout history spread in waves across the globe. The American Revolution of 1776 was an inspiration to the French Revolution of 1789. The French Revolution inspired the Haitian Revolution in 1791 — the only successful slave revolt in history — as well as a series of revolts in Europe, the Batavian Revolution in 1795 to the 1798 uprising in Ireland. The wave of revolt also swept over Latin America in the wars for independence from 1810 to 1826, led by revolutionaries such as José de Sam Martin and Simón Bolívar. (pp. 10-11) . . . Revolutionists who took part in uprisings in one part of the globe would often migrate to take part in uprisings in another. Francisco de Miranda, the Venezuelan radical who launched his country's wars of liberation from Spain, went to the United States to meet with revolutionaries such as Thomas Paine, and he participated in the French Revolution. Paine fomented revolt in the United States, England, and revolutionary France, where he was initially embraced as a hero. Giuseppe Garibaldi fought in Brazil and Uruguay before he returned to Italy in 1848 to play a central role in uprisings in Milan and Rome and a few years later in Risorgimento. (p. 11)

There is nothing rational about rebellion. To rebel against insurmountable odds is an act of faith, without which the rebel is doomed. This faith is intrinsic to the rebel the way caution and prudence are intrinsic to those who seek to fit into existing power structures. The rebel, possessed by inner demons and angels, is driven by vision. I do not know if the new revolutionary wave and the rebels produced by it will succeed. But I do know that without those rebels, we are doomed. (p. 20)

They will speak, like all dying elites, in the old language until they finally become figures of ridicule.

The last days of any civilization, when populations are averting their eyes from the unpleasant realities before them, become carnivals of hedonism and folly. Rome went down like this. So did the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires. Men and women of stunning mediocrity and depravity assume political control. Today charlatans and hucksters hold forth on the airwaves, and intellectuals are ridiculed. Force and militarism, with their hypermasculine ethic, are celebrated. And the mania for hope requires the silencing of any truth that is not childishly optimistic. . . The road to oblivion becomes, in the end, a narcotic reverie. The sexual, the tawdry, and the inane preoccupy public discourse. “At times when the page is turning,” Louis-Ferdinand Céline writes in Castle to Castle, “… when History brings all the nuts together, opens its Epic Dance Halls! hats and heads in the whirlwind! panties overboard!” (p. 33)

Communities and communal organizations that manage to break free from the dominant culture will find a correlation between the amount of freedom they enjoy and the amount of independence they attain in a world where access to land, food, and water become paramount. Such communities that share the burdens of a disintegrating society, such as the ad hoc one formed in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, are our best hope for sustaining the intellectual and artistic traditions that define the heights of human culture and permit the common good. As those who build these communitarian structures discard the religion of capitalism, their acts of charity and resistance will merge — and they will be condemned by the corporate state. (p. 43)

The goal of wholesale surveillance, as Hannah Arendt wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism, is not, in the end, to discover crimes, “but to be on hand when the government decides to arrest a certain category of the population.”. . . And because Americans' emails, phone conversations, Web searches, and geographical movements are recorded and stored in perpetuity in government databases, there will be more than enough “evidence” to seize us should the state deem it necessary. This information waits like a dormant virus inside government vaults to be released against us. It does not matter how trivial or innocent that information is. In totalitarian states, justice, like truth, is irrelevant. Any state that has the capacity to monitor all its citizenry, any state that has the ability to snuff out factual public debate through the control of information, any state that has the tools to instantly shut down all dissent, is totalitarian. The state may not use this power today. But it will use it if it feels threatened. . . Those who sweep up all our financial data, our tweets, our file transfers, our live chats, our medical data, our criminal and civil court records, those awash in billions upon billions of taxpayer dollars, those who have banks of sophisticated computer systems — along with biosensors, scanners, face recognition technologies, and miniature drones — are those who have obliterated our anonymity, our privacy, and our liberty. (p. 54) . . . And according to new laws and legislation, we can be tortured or assassinated of locked up indefinitely by the military, be denied due process, and be spied upon without warrants. The U.S. Constitution has not been rewritten, but steadily emasculated through a dirty system of judicial and legislative reinterpretation. We have been left with a fictitious shell of democracy and a totalitarian core. (p. 56)

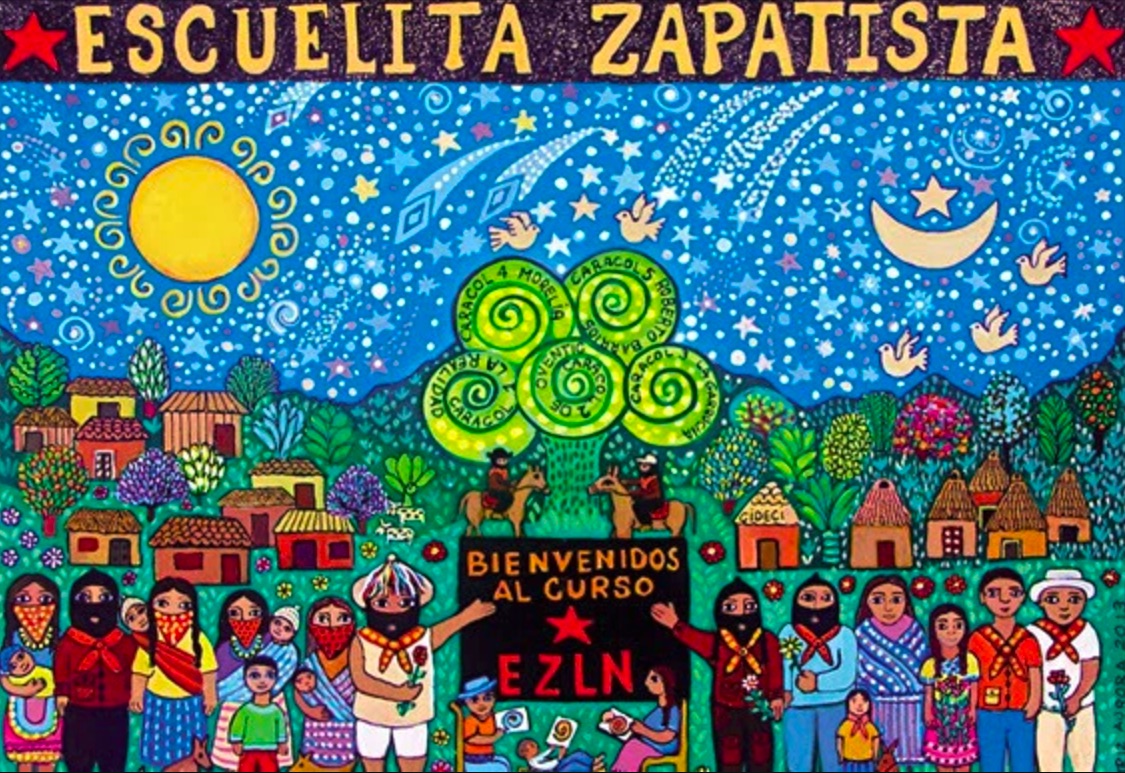

“That is why we say we are very other. Because we move as if trying on a shoe, or clothes – you measure and see if it fits, try it on, and if not then you keep looking for the one that fits.” — Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés, “Resistencia y Rebeldía Zapatistas II” (“Resistance and Rebellion II”), 7 May 2015. [o]

For every $1 that the wealthiest 0.1 percent amassed in 1980, they had an additional $3 in yearly income in 2008, David Cay Johnston explains in his article “9 Things the Rich Don't Want You to Know About Taxes.” In the same period, the bottom 90 percent, Johnston says, added only one cent. Nearly half the country is now classified as poor or low-income. The real value of the minimum wage has fallen by $3.44 since 1968.

Oligarchs do not believe in self-sacrifice for the common good. They never have. They never will. And now they have full control of the economy and the legal system, as well as the legislative and executive branches of government, along with our media outlets, they use power as a blunt instrument for personal enrichment and domination.

“We Americans are not usually thought to be a submissive people, but of course we are,” Wendell Berry writes. Why else would we allow our country to be destroyed? Why else would we be rewarding its destroyers? Why else would we all — by proxies we have given to greedy corporations and corrupt politicians — be participating in its destruction? Most of us are still too sane to piss in our own cistern, but we allow others to do so and we reward them for it. We reward them so well, in fact, that those who piss in our cistern are wealthier than the rest of us. How do we submit? By not being radical enough. Or by not being thorough enough, which is the same thing. . . .The ancient Greeks and Egyptians, the Romans, the Mayans, the Hapsburgs, even the inhabitants of Easter Island, all died because they were unable to control the appetites of their elites. The elites were able to exploit ecosystems and human beings until these civilization self-destructed. The quest by a bankrupt elite in a civilization's final days to accumulate greater and greater wealth, as Marx observed, is modern society's version of primitive fetishism. As there is less and less to exploit, this quest leads to mounting repression, increased human suffering, infrastructure collapse, and, finally, death. (pp. 64-64) . . . The only route left to us, as Aristotle knew, is either submission or revolt. (p. 66).

The Zapatistas began by using violence, but they soon abandoned it for the slow, laborious work of building thirty-two autonomous, self-governing municipalities. Local representatives from the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Councils of Good Government), which is not recognized by the Mexican government, preside over these independent Zapatista communities. The councils oversee community programs that distribute food, set up clinics and schools, collect taxes. Resources are for those who live in the communities, not for the corporations that come to exploit them. And in this the Zapatistas allow us to see the future — a future where we have a chance of surviving. (p. 72)

Throughout history, those who have sought radical change have always had to begin by discrediting the ideas used to prop up ruling elites and constructing alternative ideas and language. Once ideas shift for a large portion of the population, once the vision of a new society grips the popular imagination, once the old vocabulary no longer holds currency, the power elite is finished, although outwardly it may appear that nothing has changed. But this process is difficult to see and often takes years. Those in power are completely unaware that the shift is taking place. They will speak, like all dying elites, in the old language until they finally become figures of ridicule. In the United States today, no person or movement can program the ignition of this tinder. No one knows where or when the eruption will take place. No one knows the form it will take. But a popular revolt is coming. (p. 85)

Even as it reveals what is happening around us, it honors mystery. It saves us from ourselves.

By the 1980s, Mandela and the ANC (African National Congress) leadership had recognized that as the struggle against apartheid evolved, it was the strikes and boycotts, along with the organizing work by nonviolent groups such as the United Democratic Front (UDF), the ANC's political wing, that were the best instruments for crippling the apartheid regime. The ANC's tiny rebel bands were increasingly ineffectual. South Africa heavily patrolled its borders and stymied most cross-border infiltrations and attacks. Armed attacks frightened white liberals — who were natural allies I the anti-apartheid movement — and were used by the apartheid regime to justify state violence. It was the growing use of “noncooperation” by the black majority that brought the economic engines of the country to a halt. . . The tactic of nonviolent protest also garnered support from the international community, which eventually imposed sanctions. If the ANC had invested all its energy in an armed movement rather than mass mobilization, it would never have triumphed. Mandela, although he never renounced violence, understood by this time that the movement had become a civil insurrection rather than an armed insurrection. (pp. 98-99)

It was the poems of Federico García Lorca that sustained the republicans fighting the fascists in Spain. Covering the war in El Salvador, I saw that the rebel units often traveled with musicians and theater troupes. . . Culture, real culture, is radical and transformative. Culture can express what lies deep within us and give words to our reality. Making us feel as well as see, culture allows us to empathize with those who are different or oppressed. Even as it reveals what is happening around us, it honors mystery. It saves us from ourselves. “The role of the artist, then, precisely, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through the vast forest,” (James) Baldwin writes, “so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place." . . .

Rebellion requires an emotional intelligence. It requires empathy and love. It requires self-sacrifice. It requires honoring of the sacred. It requires an understanding that, as with the heroes of classical Greece, one cannot finally overcome fate or fortuna, but that we must resist regardless. . . . “Ours is a time that would have sent the Greeks to their oracles,” (Harold) Goddard writes. “We fail at our own peril to consult our own.” (pp. 224-225)

CHELLIS GLENDINNING is a writer and psychotherapist specializing in trauma recovery. She is the author of seven books, including the award-winning Off the Map: An Expedition Deep into Empire and the Global Economy and Chiva: A Village Takes on the Global Heroin Trade. A US citizen, she lives in Chuquisaca, Bolivia. chellisglendinning.org

Add new comment