Che Guevera in Bolivia, 1967, not long before he was assassinated.

COCHABAMBA, BOLIVIA — When I first arrived in Bolivia in 2006, I found it easy to meet political activists. At the cantina Co-Café Arte, amid posters of Frida Kahlo's monkey and Picasso's Guernica panorama, I fell naturally into the sea of debates. Caracol was another hotbed. Filled with the smoke of Cuban Habanos and the songs of Mercedes Sosa, its tiny rooms were vibrating with urgency.

I happened upon Jorge Bayro Corrochano at the Caracol in 2012. When I walked in, I spotted Fernando 'Boxer' Machiceo nursing a drink at the bar. Boxer was one of the most committed urban supporters of the indígenas who were fighting the government's global-economic plan to cut a superhighway through their constitutionally-protected territory, the traditional lands where they still practiced hunting-gathering; also home to the nation's richest biodiversity. Boxer had made both three-month protest marches from Trinidad to La Paz and was forever traveling from the reserve to the city to raise funds, sell videos, and speak on the radio. He stood up and, with his old compañero Jorge Bayro, moved us to a table in the back. Bayro immediately launched into a rap on the significance of insurgency. He was one of the few survivors of the now-largely-forgotten guerrilla revolt known as Teoponte.

Different degrees of enrollment existed. Those tasks of greatest risk were assigned to the inner-most circle.

Teoponte was conceived as proof to the world that the anti-totalitarian movements in Bolivia had not been crushed just because Che and his band of rebeldes had been gunned down. It was 1969-70, and this new guerrilla — the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) — was made up of some 70+ budding fighters referred to as 'the sons of Che.' They were Christians, Communists, and Trotskyites: the majority middle class, many students, while a few were obreros or campesinos [workers or peasant farmers]. With heroism pumping through their veins, on 18 July 1970 they took their boots, jungle fatigues, and Uzis to the selva [jungle] not far from La Higuera where Che had been shot dead in a schoolhouse and then transported by helicopter to Vallegrande.

Just as with Che's army, though, there were not enough of them, they didn't have enough armaments, and they didn't know the terrain. But perhaps the most significant factor in what happened was the cocky self-importance of Bolivia's bellicose jefes [leaders and generals, etc., who decide military strategy] due to their recent triumph in doing away with the most notorious revolutionary in the world. The military was gung-ho to squelch this nascent uprising; their orders were, “Not one wounded, not one prisoner, all dead.” The first to be captured were forced to dig their own graves before being machine-gunned into the holes. Near the end the army mounted more than 1000 soldiers against the dwindling cadre of starving rebels, using internationally prohibited napalm. By 1 November they had perpetrated the deciding massacres — with only nine survivors escaping the carnage.

To talk about Teoponte, Bayro and I met on the patio of one of Cochabamba's old hotels in February 2016. Over ice tea he revealed details about his life that he had never before divulged.

Inti Peredo's funeral, 1970. >

JORGE BAYRO Back in the 1960s, Cochabamba was a small town where everyone knew each other. Our friends belonged to upper middle-class families, and we didn't have any kind of real relationships with those below our class. Then something happened. Through music and books new ideas arose. "There's more to life than this!” chimed the new voices. We started to challenge the establishment. It may seem ridiculous nowadays, but it was serious then: letting your hair grow long. It wouldn't matter if you were a good student or led a conventional life, some policeman would show up and drag you to a barber shop! Can you imagine that?

The experience of Che's battle and the rising of Latin American literature by authors like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Jorge Luis Borges, and Julio Cortazar influenced us. Early in the '60s, my eight brothers and I were entering adolescence. It was a hard time in Bolivia. We had grown up with our family's memories, inherited from our parents and grandparents who had lived through the Revolution of 1952. Most of them held a negative view of that achievement; they were its enemies because their land, farms, houses, and indigenas were taken away.

CHELLIS GLENDINNING They owned people?

JB Sure they did. The system was called pongo. We rebelled, saying “It doesn't have to be like this.” We were a bunch of kids searching for truth. We distrusted just about everything. We read history, but now with a critical eye. You've got to keep in mind we were not in touch with miners, factory workers, or farmers, yet we were catching a glimpse — in our hearts. Even though the conversion mainly happened though books, we got to understand their struggles, what they were going through, like persecution and massacres.

Something similar was happening in politics. Newly organized parties made their appearance like the Communist Party (CP), while the earlier leftist parties were decaying. The CP grew, and Trotskyite participation was strong. We started questioning religion — in the sense of its role as a partner in crime with injustice. Small youth groups blossomed at universities, as well as those organized by rebel Dominicans, Augustinians, and priests from the Company of Jesus. They would say, “One's got to rebel. The Church is wrong.”

CG Liberation Theology?

JB That would arrive later in 1968-69 when some important groups made their appearance. The most popular, I think, was FRUC.

CG What does FRUC stand for?

JB Frente Revolucionario Universitario Cristiano. It was organized by priests. A more potent group was Partido Demócrata Cristiano, a social-democracy party that continues today. My brothers and I started traveling during holidays, but it wasn't the old journey into nature to have fun anymore. I went to the mines. This began when my parents passed away.

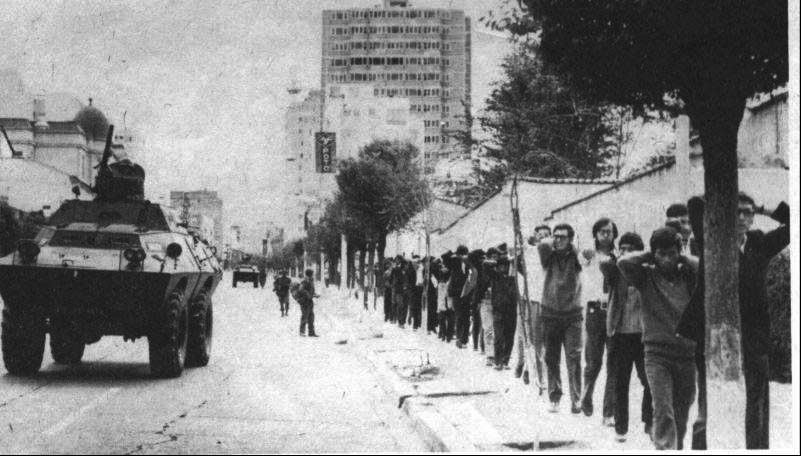

The military take-over begins. >

CG When was that?

JB In 1960 and 1961. That's when my brothers and I began to rebel. We decided to live alone — without adults. It was a scandal! Everyone looked down on us and whispered, “This can't bring any good.” But we did it anyway. Ours was a libertarian home. We had respect for the culture we were crafting. We put away the fancy, classical furniture and made our own out of wooden crates that we got for free. The older siblings would take care of the youngest. The house was spick-and-span. Whenever one entered, one had to take his or her shoes off. It didn´t matter who you were. At the front door was a small piece of furniture that we built. Guests would take their shoes off there like the Japanese do because we cared about the labor of the person whose job that week was to clean the floor. It was a matter of values and respect.

CG Anarchy?

JB Yes. And a time came when 40-50 people a day would drop by the Bayro household. Do the math: nine brothers times five friends. The house was like a cauldron where something was always brewing.

CG One brother, José, is now a well-known painter and sculptor in Mexico.

JB Carlos was a promising artist, too. By the age of 14, he already painted well, and his work brought art into the house, not classical religious art but a broader culture of art. Before he was hunted down, tortured, and murdered, he was also a dirigente [leader] in the Movemiento de la Izquierda Revolutionaria (MIR). We had a library. Marxism, Leninism, el Che, Latin authors. All of it forbidden stuff. I remember reading For Whom the Bell Tolls when I was 12. An old lady asked “What do you read?” and so I showed her the book. She started yelling “Shame on you!” and called a priest to explain how serious the matter was.

CG I imagine that these experiences laid the ground for becoming a guerrillero . . .

JB For sure! The great strategist Inti Peredo returned to Bolivia from Cuba in 1969 to re-organize Che's war which, as we all know, came to an abrupt end in 1967. The Cubans didn't agree with this new plan, but helped us anyway. A wing of the Liberación Nacional (LN) party of Chile, of which Salvador Allende was a member alongside some of Che's militants, also sent support. By 1969 we were well-equipped, our storage houses full of ammo and armaments, our logistics fine-tuned. We had boots, bags, up-to-date weapons and communication equipment. We could launch a long-term resistance, and when the urban repression started, we fought back.

Such is one way for self-preservation, not hiding out in a pit waiting for the enemy. Hell, no.

CG So there was armed warfare not just in the mountains, but in the cities?

JB That's right. Especially in La Paz, Cochabamba, Oruro, also in Santa Cruz. We lost our storage houses. And Inti was murdered. Our leader! Dead!

CG In the city?

JB Inti fell at a safe house. He was defending himself when a grenade thrown through the window blew him to shreds. Despite all the obstacles, the ELN made the decision to continue, a decision that is criticized in retrospect. Yet we were under pressure regarding our responsibility to Che, Inti, the organization's history, and what was going on throughout Latin America. It was a time when dictatorships were taking over governments everywhere, and that alone justified taking action. To my mind it was a mistake. But we gathered all sorts of ammo and weapons from those who were helping us. Like, for example, imagine you were there, Chellis, you would have helped us. Nobody would know, but you'd be committed to the cause and along with you, some of your more radical and trusted friends.

CG So then . . .

JB I got my first gun in 1969 — a .45. I was already being hunted. A “MOST WANTED” poster even featured my mug! I didn't live with family anymore; I was in hiding. My orders were to stay in the city so I had to say farewell to my comrades on their way to the mountains. I remember I handed my .45 to a friend because he would need it more that I did, and he said, “But you can't go around unarmed.” So he gave me a grenade. Picture me carrying around a grenade!

CG What was your job?

JB We were organized in a vertical fashion like the military, but clandestine because we were being pursued. It was for that reason that you didn´t necessarily know who the others were. Each team had its specific tasks. Our first-and-always comandantes were Che Guevara and Inti Peredo. About five people were on the central team, some of whom were well-trained personnel who had been involved in the planning and organization of Che's activities at Ñancahuazú. Then there were the squads. Below them came the new recruits undergoing training. Those who were experienced would have their own gun; the others went unarmed. Different degrees of enrollment existed. Those tasks of greatest risk were assigned to the inner-most circle.

Rounding up university students. >

CG Are there any survivors of that central group?

JB Yes, but they are too few, and it's hard to get to see them. Maybe I could arrange that you meet one of them. But you need to know: the personal stories of those who survived are tragic. I mean, it was war, and wars leave deep scars. Also, some people change over time; those closest to you can harm you. It's not easy to survive, or be a survivor.

CG What was your role in the structure?

JB When I entered the ELN, I was 18. I had been trained already. I had studied at a university in Chile.

CG What did you study?

JB I studied footwear at the Tech Institute Bata. It's a shoe brand called Manaco in Bolivia. They still have that institute in Chile, next to the factory. I had left home in search of expanding my boundaries. Cochabamba had become a small world. In Chile my revolutionary, anti-imperialist commitment became clear. I was becoming aware of reality, and I was dedicated to building a socialist world, as was the slogan back then. I met friends from Cochabamba who also studied at Chilean universities. Some studied social sciences, mostly sociology. I hung out with them. At the time Chile was Latin America's most democratic model. A lot of healthy debate went on. And demonstrations. Inti Peredo showed up on his way from Cuba to Bolivia and invited us to re-initiate revolutionary activities. One by one, we started coming back. Chileans from LN were sent to join us, too. Others came from abroad.

We organized ourselves in small groups. The most urgent matter was formation. I was the youngest so the elders put their efforts into educating me. I distinguished myself with my commitment, decision-making, and combat skills. I became an explosives expert. A gun expert too, as one thing leads to another. Along with two comrades — both of whom died in Teoponte — we crafted all the explosives to be used in the mountains, and we made more for our urban troops. The place looked like a gun store where you could find all sorts of armaments, guns, grenades, and anti-personnel weapons. We crafted everything guided by Vietnamese craftsmanship, and we made it all with recycled trash, tin cans and the like. When our depots were eventually taken down, we started to make sleeping bags, hammocks, raincoats, everything that would be needed.

These new generations don't pledge themselves to the revolutionary call. People have stopped reading, they've stopped thinking.

CG I guess your Bata studies paid off.

JB Even more important were my studies at Saint Augustine School in Cochabamba. There they taught not just math, languages, and philosophy but also handcraft skills like woodwork. All that helped. Besides crafting all that would be needed, actions were taken. Like stealing money.

CG What do you mean?

JB We referred to it as “expropriation.” Stores, banks — this is a common method among Latin American revolutionary movements. The Tupamaros* would kidnap in order to get rescue money. To build safe houses, one person would play-act “normal” to rent a place. The neighbors would see him coming and going, leading a regular life, while we inside were toiling away, building armaments, training, hiding the pursued.

CG How many people were working in the cities?

JB I might guess 200-500. By the time of the Teoponte massacres, I calculate that we were 500 in the city and in the field.

CG The end of the struggle happened in 1970. What did you do then?

JB I left Bolivia. Most of my comrades were dead or disappeared. Others fled. The largest group remaining went to Allende's Chile. I have never requested political asylum or been a political exile. I've just carried on fighting. My contacts in the highest rungs of the government offered me Chilean nationality, scholarships, a job. I rejected all that in order to keep fighting. The Junta de Coordinación Revolucionaria was just being founded, including Uruguay's Tupamaros, el Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo Argentino, Chile's MIR, Bolivia´s ELN. I joined the junta. I fought in Argentina. I went to Peru representing the junta. I traveled to places as an international soldier and did many things. But I don't think this interview needs that sort of information; it's wiser to keep certain things unsaid.

Map of land-locked Bolivia, surrounded by its neighbours. >

CG Point taken, my friend.

JB In 1976 my orders were to return to Bolivia. Our people were being jailed or killed again. I went to the mines in Llallagua, and there I chose not to hide out, but rather to become a miner. Wearing my helmet and boots, carrying a lantern, I was disguised. I'd walk from my rented room to get water, and I'd eat in single-men dining halls. Everyone knew me. Such is one way for self-preservation, not hiding out in a pit waiting for the enemy. Hell, no.

I found an unusual willingness to join the movement there. I managed a column of miners called Juana Azurduy de Padilla. We got arms and performed combat maneuvers. Then real combat. The police would search sky and earth for us, yet in our miner's clothes we'd be right under their noses. They couldn't figure out who were the ones they hunted. Meanwhile, the ELN decayed. They destroyed us, killing comrades, jailing others. There was nothing for us to do but start over. But by the time democracy made its way into Bolivian elections in 1983-4, we were too few.

By now, decades have passed. These new generations don't pledge themselves to the revolutionary call, and it has been silenced with the entrance of globalization's unlimited access to internet information. People have stopped reading, they've stopped thinking. If there is a wonderful 500-page book, they read a ten-page summary. I have stopped believing in hope for a human way of life. We have fallen into oblivion. Our very history is forgotten. But people can't exist without history.

CG I can't thank you enough for telling me your history.

JB Until my last day I will be a living testimonial to my comrades. I no longer give talks at conferences or participate in demonstrations. I go unarmed. But I do my work mindfully. I discuss, I fight. Ha! Just like a loco.

* A member of a Uruguayan Marxist urban guerrilla group of the 1960s and 1970s.

Originally published in The Journal of Wild Culture on June 25, 2016.

JORGE BAYRO is still recognized on the streets of Cochabamba and called by his revolutionary handle "Ramiro." He has worked in hotel management, community organizing, and election monitoring and was principle researcher for Gustavo Rodriguez Ostria´s Teoponte: La otra guerrilla guevarista en Bolivia. He still watches his back.

CHELLIS GLENDINNING is a psychotherapist specializing in recovery from trauma and the author of seven books. These include My Name Is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization and Chiva: A Village Takes on the Global Heroin Trade. The latter won the (US) National Federation of Press Women book award for nonfiction. Her latest is the book-blog, luddite.com. Chellis' website is chellisglendinning.org.

Add new comment