OAXACA, MEXICO — A decade ago, I jumped on a plane with my best friend and against all odds we arrived at the Coachella Valley Music Festival. The weekend was so profoundly magical that I decided to ride off on the same caprice the following winter, backpacking through the Sacred Valley and the Peruvian Amazon. Something happened. Something triggered. I fell in love with the world. And thus began a decade of planes, trains and automobiles, life-long and cursory friends, other languages and other worlds, and lives and loves lived and lost.

After a few years of backpacking, I began to demand more from myself in my travels. It turned out that, believe it or not, sight-seeing can get boring too. I decided wherever I travelled I would learn something substantial (i.e. a language, a skill, local cuisine, etc). In the last third of the decade I’ve found myself being challenged further, to go beyond the idea of ‘what kinds of intangible things can I take back with me' (to colour my fade-to-grey North American city life). Yet what followed was not transcendent realization. What followed brought me face to face with some very difficult questions and painful insights about the nature of travel in the context of western culture. What followed was an understanding that the myriad ways in which westerners travel and view other cultures, is inherited from narratives over 400 years old – narratives most westerners assume are no longer being told. It is these stories we tell and are told over and over, coupled with an impoverished sense of belonging, that define the particularly western way of travel.

As diverse as travellers are, I've seen an underlying current that moves tourists, and especially backpackers, towards an indistinguishable something.

If you have ever backpacked through Thailand or Peru's Sacred Valley or worked in Australia or New Zealand for a year, you might know there are as many types of backpackers as there are curries in Thailand. As diverse as travellers are, I've seen an underlying current that moves tourists, and especially backpackers, towards an indistinguishable something. Meaning? Beauty? Adventure? A new home? It is here, with this question, we find the current muddied. Where exactly this current is taking recent generations of wayfarers is impossible to pinpoint. It's a question worth asking, but arguably not the most pertinent one. What could serve us better is not to ask what it is we are looking for, but why we are looking for it in the first place.

And, what is it about other cultures, or perhaps our western culture, that offers solutions for what ails us?

One answer might be curiosity.

The Spectator Mentality (or, the Tourist as the Personified History of Anthropology)

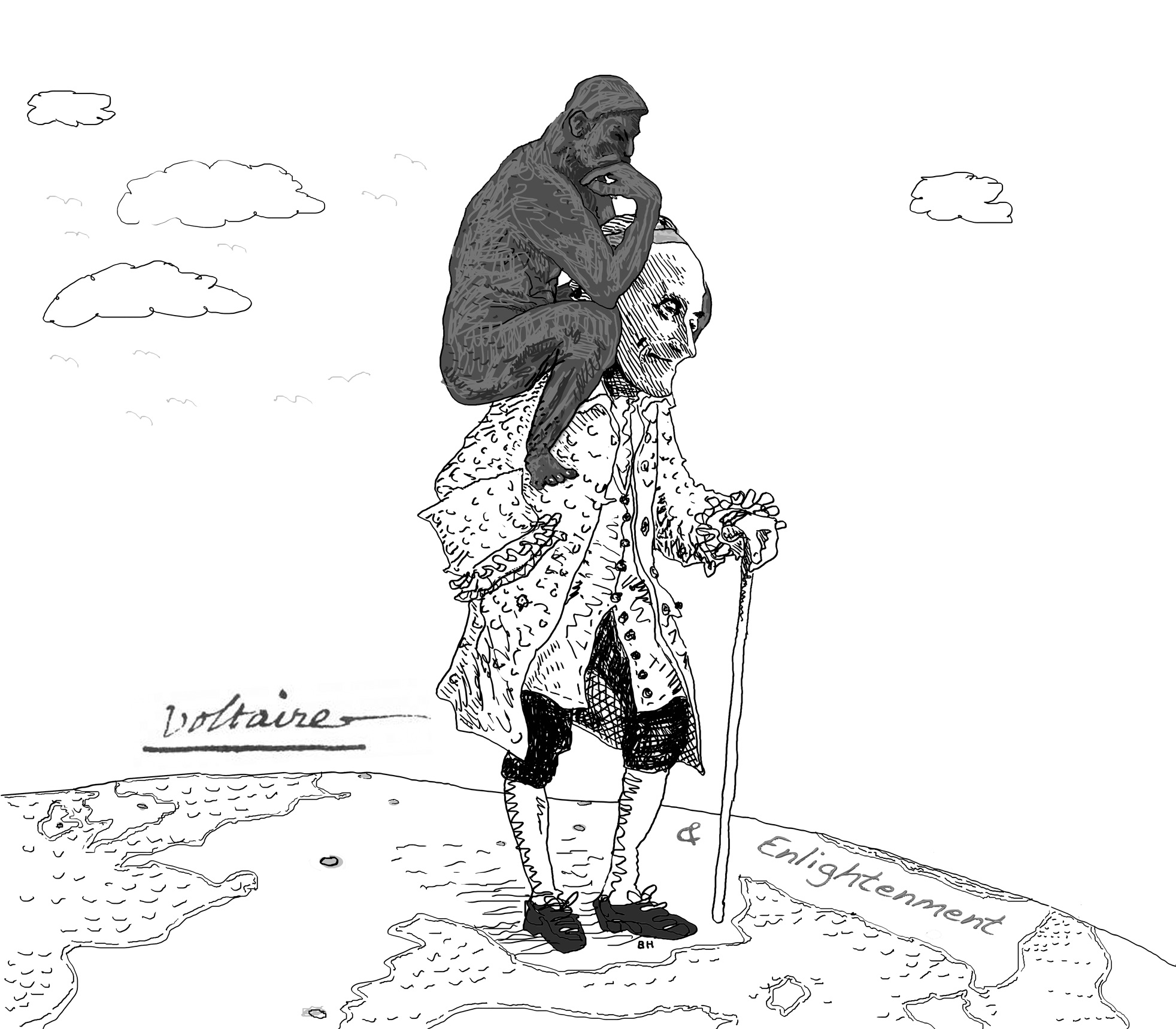

A sunburnt, wayfaring American backpacker and a 18th-century English anthropologist walk into a bar... No, it's not a joke. It's more of a riddle in the form of gibberish. Here's a hint: one is the direct cultural and intellectual descendent of the other.

Let me explain. There have been five major directions modern anthropology has taken in the last four hundred-plus years in European thought. Their foundations and evolution are as follows:

• The initial Christian perspective, going back at least five centuries, often generalized non-monotheistic cultures as devil worshippers. These cultures were viewed through European Christian canons and as a consequence, concepts of good and evil took centre stage. This was also the view taken by earlier Christians and other monotheistic societies as they pillaged and missionized their way across the globe.

• In the late 18th century, in what is today called the Enlightenment, Immanuel Kant famously 'dared' the intelligentsia 'to know.' Perhaps this fell on deaf ears, as the precursor to the modern anthropologist, the Christian rationalist, chose to debunk rather than condemn, replacing titles like “devil worshippers” with “impostors” and “jugglers.” Perhaps the ownership of knowledge was more important than the acquisition of it.

• Later, in the second half of the 19th century, when the study was formalized as such, early anthropologists began as “white men studying primitives,” entrenched with the academically Darwinian desire to measure and catalogue human cultures.

• The study deepened in the 20th century by more accurately portraying non-theistic cultures in a kinder, neutral light, but still doing so through a loose monotheistic lens.

• In the mid-20th century, the march towards objectivity meant anthropologists were not just studying other cultures, but living in them and often participating in the community and their rituals.

• Finally, the last few decades of the century saw a move towards allowing non-European cultures to tell their story, but of course only through the words of the anthropologist.

Anthropology was born out of a myriad of scientific and rational uprisings and progressions in the west, and if we take this into consideration, it is possible to understand the evolution of anthropology. In my travels, I've noticed a specific dynamic that tends to define westerners in relation to the cultural “Other” — in this case, different cultures, peoples, languages — by all forms of tourists. Backpackers and package tourists alike unconsciously inhabit what I will call the spectator mentality. It is this mentality, largely (and unconsciously) informed by the obsolete scientific and cultural worldviews, that informs the western capacity to engage and learn from the cultural Other. In short, when westerners travel, they do so from the point of view of a centuries old worldview, without ever knowing it.

The spectator mentality can be seen at zoos, a defining institution that separates civilization from the wild. It can be seen in museums, where all history and cultures are set behind glass and made to look dead and gone. It can be seen in open-kitchen restaurants, where customers stare, uninterrupted, at their food being assembled. It can be witnessed in most forms of live entertainment, including sporting events, where people maintain a spatial disconnect, but with a gaze of pre-determined judgement and expectation. In other words, people engage, unconsciously, in an empty stare as if the person or thing they're staring at isn't even in the room, like the consuming gaze of the TV viewer, something akin to a one-way mirror. But in every case, the other people (or in this case, cultures) are there, alive and perhaps strangely aware of what is happening in front of them.

Most tourists regarded our village as an interesting prop in a world observed externally — like a TV program.

Before the 20th century, Europeans showcased caged peoples in what we now call “human zoos.” Today, after the centuries-long and arduous progression towards ethics and equal rights, we have only animal-based zoos. Notwithstanding, animal captivity today is justified by the enduring research efforts to catalogue and preserve the lives of animals quickly becoming endangered or extinct.

Wait. Read that last line again. Does that sound familiar?

Can you start to hear the whispers of the early anthropologists alive in spirit in the 21st century? Can you notice the hushed influence of history? Can you see that western culture, despite its movements towards equality, is still rooted in centuries-old worldviews that haven't quite let go of their grip on the cultural narrative? Perhaps the past is not quite as dead as we'd like to believe.

Today, package tourists exemplify the spectator mentality, in the very obvious fact that their vacations are literally pre-packaged — moulded in a way that sanitizes what they experience, and in ways that recreate their own cultural needs and preconceptions of the world. These “vacations” (perhaps not unsurprisingly the word means vacant and free from duty/obligation) quite literally remove the indigenous people from their lands and consequently remove the tourists from any possibility of an intercultural learning experience.

Entire towns and cities have been built in the last 50 years for this reason alone. Cancun and Dubai are good examples. In these cities, the westerner has every possibility of experiencing western luxuries without ever having to experience the rich culture of the place in which they have arrived. Granted, some tourists are pining for such a cultural experience, however they are more often than not sold commodified, watered-down, government-sanctioned reproductions of the cultural ethos. Or, in other words, entertainment.

I offer the following quote with a question to ponder: can we differentiate between the tourist spoken of and an 18th century European anthropologist?

"There was an implied curse in being looked at as a dead object by unknown people who never really wanted to know you. Most tourists regarded our village as an interesting prop in a world observed externally — like a TV program. Mayans, like other peoples and places throughout the world, were there as curious entertainment, something simple and lesser than the tourist's strange, synthetic, machine-made way of life." — Martin Prechtel, a Mayan shaman and author, who for a time lived on the shores of Lake Atitlan in Guatemala.

Is it possible that westerners have inherited a way of seeing the world that creates and reinforces a perceived cultural superiority (and henceforth an inherent segregation and barrier between engaged interculturality)? If we tried to set the average western tourist alongside an anthropological epoch that best represents their view of other cultures, their mindset would be situated, anthropologically, at least 100 years ago. So why is it that such a modern culture, a culture that prides itself on being forward thinking, is so obliviously stuck in the past? If we can see that anthropology has moved well beyond its own outdated, ignorant, and obsolete past, then why doesn't the rest of society?

How Long Will it Take?

Part of the western cultural perspective is brought forth by the scientific method and Newtonian principles, coupled with Cartesian philosophy. Descartes’ work was the foundation for the modern western assumption that humans have no souls and that animals are purely automata. His work is still the foundation for modern materialism. Early scientific tradition came to presuppose a certain objective lens that was based around the scientist or experimenter’s role in using the scientific method. By doing so and being able to repeat and thus validate findings, objective truth could be found outside of popular consensus or religious transcription (i.e., what God says).

In the past hundred years, quantum mechanics has shown that hypothetical objective reality posited back in the 1700’s is non-existent, with examples such as Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, and the observer effect. The former signifies that sub-atomic particles exist in a cloud of probabilities. The latter proves the scientist's presence or even intention in an experiment can influence its outcome. However, scientific truths are not the same as cultural truths. Such changes take time to integrate. Often a long time.

As we can see with quantum physics, publishing and proving hard science does not mean a culture will change in the face of new truths. In the last century, western culture (via public education systems) has become much more science-hungry than ever before. As a result, the march towards certitude and fact and synthesis is top-heavy and unwavering, despite the obvious uncertainty and subjectivity that quantum science proves about the nature of reality. After 100 years of quantum physics proving that our universe does not look like the way our textbooks tell us, the culture still embraces an obsolete perspective.

Slowly, often very slowly, scientific truths have tended to become cultural truths (at least in western history). Even though certain breakthroughs like those of Darwin or Newton or even Descartes are readily accepted in academia, it can take decades or even centuries for these ideas to become institutionalized into the orthodoxy of a culture. The concepts, given enough authority, start to weave their way into the fabric of the cultural cloth. These truths then tend to take root in institutions and over time, solidify into cultural memory. But when new concepts become preconceptions in societies that stagnate and refuses change, a kind of cultural amnesia erupts that forgets the story was once told differently. And thus amnesia and authority become encapsulated in a phrase that whispers: “It's always been this way.”

It seems that European-based western culture, in becoming globalized western culture, has brought this philosophical baggage to the far reaches of our planet. If academic truths take time to become integrated into the mainstream, the question becomes: in a time of seemingly inevitable and catastrophic environmental destruction, how much time is needed, and do we even have enough of it to wait and see?

Towards the end of the night, one of them turned to me and asked, “Do you feel lonely?”

Searching and Exploring

Adventure has been a travel prescription for me for as long as I’ve had the “bug.” But adventure is a noun. And in the west, it has become something to be consumed. It doesn’t happen without a reason either, at least not when most people can only spare a small amount of time away from home or work. Too often it seems adventure stops being the desire for spontaneity and instead becomes the hallmark of escapism.

Western culture is a culture whose history has forsaken what preceded it to such an extent, that all of these extraordinary opportunities to travel stem from a kind of homelessness that is incredibly elusive in its capacity to be defined easily. In the last 50 years, this homelessness or longing has been commodified and subtly reappropriated into coming of age rituals. One particular approach to this longing is the desire to “travel the world and find yourself.” Such ritual has become the commonplace in western society by those who feel a visceral sense of loneliness. An insatiable appetite for discovery, adventure, and partying seem to be major features of traveller culture. But what is it about one's sense of home that demands these needs be met elsewhere? Let me submit to the reader that the western desire to discover new places and cultures, to engage in adventure whenever possible, and to party by any means necessary all stem from a cultural and historical amnesia. We have gone so long without what is needed, that we can't even remember what that is.

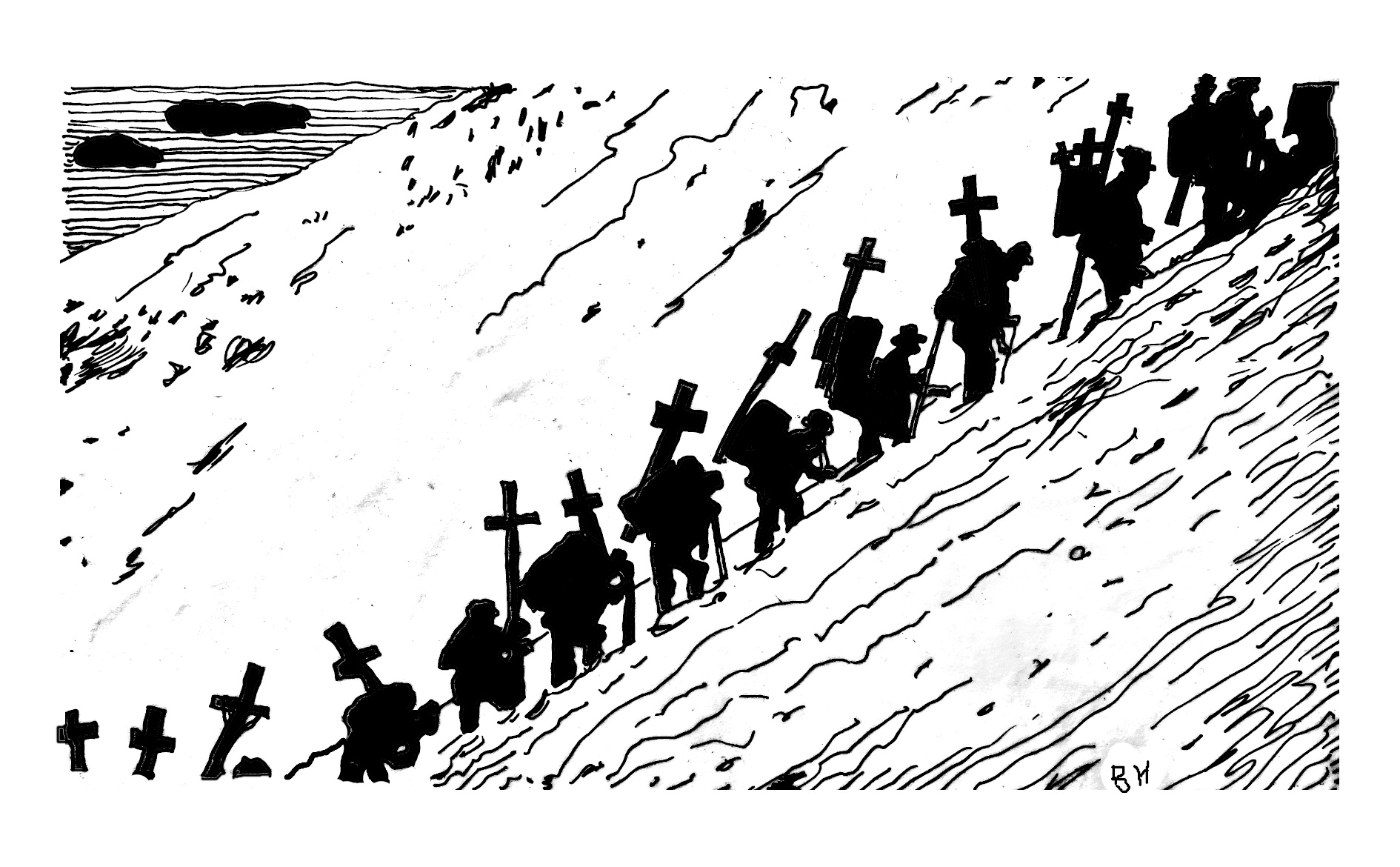

As with anthropology and mainstream science, we can see that the past is not gone, but has followed us into the present without us knowing. As neo-liberalism opened borders for travel and the influx of western liberal culture into other parts of the world, the old, colonial military generation became the new, uninitiated, adventure-seeking party generation. Similarly, the curious and often missionizing Christian anthropologist became a save-the-world, school-building volunteer. The masks are different, but the story remains the same — the morally bankrupt and the morally self-righteous acting out their ancestors' parts. They have become actors in a tragicomedy which they do not realize they've become a part of, which they do not realize they are accelerating.

Such patterns carry on in other ways, too. There is a subset of travellers of the existential variety. They generally do not know what they are looking for in their travels, but they are without hesitation searching for something, and the ones who claim to understand this predilection sometimes call it “meaning.” It is here we find the subscribers to the travel-the-world-in-order-to-find-yourself travellers. But how does one go about the world searching for an intangible, culturally-derived thing, when they already come from a culture that ascribes its own meaning? Visiting shrines and gurus and sacred places of various cultures and spiritualities that belong to other peoples and other lands? The pattern begs the question, “Why does one need to do this at all?” What is at the root of their perceived lack of meaning or fulfilment? Perhaps it is possible these pilgrims are (or have been) misguided from the very beginning. Perhaps their search isn't brought on by emptiness, but by loneliness. Perhaps what they are searching for isn't meaning, but belonging.

It is often been said to me that indigenous peoples, still of the hunter-gatherer disposition do not understand the western conception of travel — especially in the context of vacationing and backpacking. The question might arise, “why would you ever need to leave your home?” What could it possibly be about home and our sense of belonging in the west that drives people to search out and need more from the farthest reaches of the planet?

Recently I was in Oaxaca City having beers and conversing with two other backpackers from Australia about this very subject. The conversation was amicable and even engrossing for these two who hadn't considered the role of culture and history in their own travels. Towards the end of the night, one of them turned to me and asked, “Do you feel lonely?” Although the question could've been taken as an invitation, it was clear she was seeing the same insights towards something she couldn't fully understand. After being asked this for the first time in my life, I took a long pause, looked at her calmly, and said “I think I am.”

Being, Becoming, and the Forgotten Breadth

We think of belonging as permanence, yet all our homes are transient. Who still lives in the house of their childhood? Who still lives in the neighbourhood where they grew up? Home [has become] the place we have to leave in order to grow up, to become ourselves. We think of belonging as rootedness in a small familiar place, yet home for most of us is the convulsive arteries of a great city. Our belonging is no longer to something fixed, known and familiar, but to an electric and heartless creature eternally in motion.” — Michael Ignatieff, The Needs of Strangers

The question of existence that western philosophers have been asking for 2500 years is this: is our existence (or existence itself) couched in being or becoming? These are the options: Being is the immanent “I already am everything I am and ever wish I could be, I simply have to awaken to this understanding.” Becoming is the more commonly held understanding that “I am not yet what I could be, but through various methods or techniques I can achieve my goals.” Immanence and transcendence.

Despite the rich history of this dualistic argument, it is conceived of with a veiled foundation of individualism. Both these voices on existence are couched in the “I” and what is or might be. What is for me. But if we can step out of this presupposed necessity towards the individual, what might we encounter? If we can take this question out of the box of the individual and see it in the eyes of ecology, what would we find? What does existence look like to a village? It looks like a circle. It is belonging. The very question of existence and the necessity one might feel to ask such a question is practically irrelevant in a society in which you belong to, in which you are needed, and in which belonging carries with it a reciprocal responsibility between you and the community.

In Belonging: The Paradox of Citizenship, Adrienne Clarkson expounds upon the necessity belonging has in human relationships, but applies it to citizenship. Her underlying assumption is that belonging, which is an inherent need of the individual, is bound to citizenship (and thus the state). As she traces the roots of citizenship and its likely historical extension from village-belonging, she fails to consider that the very examples she cites as the movement towards the citizen is actually a movement away from authentic belonging.

So, how does one attempt to approach loneliness and belonging (or the absence of it) when they live in huge cities in progressive, liberal democracies. In Canada, for example, when the state-driven culture facilitates and promotes multiculturalism (as it does in Canada), why is the issue of belonging so important, and its dialogue so vapid? How could anybody ever feel lonely in a place where millions of people are interacting each day? And yet the cities are awash in lonely people. Is this not at the very least paradoxical and borderline insane on any other level?

The word “indigenous” means to “belong to a place.” Place, here, is not representative of an abstract area, but of land, of Earth and the specific land a society has been entrusted with. “Indigenous” cultures understand that with belonging, people don't just belong to each other and their community, but they principally belong to the land — to the Earth. So, when institutions arise like the city-state and later the nation-state, belonging is no longer a consequence or responsibility to your relationship with the Earth, it is now permitted only by your relationship with the government. Henceforth you have the creation of the citizen, which defines and reinforces the relationship between the state and the individual. This in turn, delegitimizes belonging as it originally existed — belonging between and within communities and the land, which in its basis is mutually reciprocal, instead of hierarchical, like most western power structures. And so today, we have generations of youth wandering the Earth, searching for what is directly below them, that which they are literally inside of.

So what does this have to do with travel? Well, I can guarantee that my loneliness (or lack of belonging) has nothing to do with my citizenship because I have traversed Canada and have been all around the world touting a passport from the “Global North.” Consequently, I have discovered that filling out an online quiz or listening to my intuition to find out which country might be best for me, or discovering which peoples are most like me, could never cure my sense of loneliness. I have a large, loving, supportive community of family and friends, and yet, it's still there. But, back to the question at hand. The citizen and the state are both abstractions of the human being, as well as historical and political lines drawn in the sand. Both are abstractions defined in strict cultural and historical terms. So, if we were to remove these abstractions from our sense of belonging, how could we begin to define ourselves? Where would our sense of belonging lie?

Until you give up the idea that happiness is someplace else, it will never be where you are.

Grass is Green. Period.

There is generally a profound and beautiful curiosity travellers have to want to explore the planet. Is that normal? Is it strange? Even in the western world, most people grow up, live and die in the same city, if not the same region, often without travelling outside their own country. Those who do leave the nest, often repeat their temporary (and sometimes permanent) exodus into other parts of the world with a growing sentiment that the grass is always greener on the other side. This is most obvious among backpackers.

The concept of “destination addiction” fits in here quite well, a term coined recently to describe those, much like myself, who have felt the “grass is always greener” in X country, or once I get back home, but for whom such hope always falls short. Robert Holden founded the term, and describes it as follows:

A preoccupation with the idea that happiness is in the next place, the next job, and with the next partner. Until you give up the idea that happiness is someplace else, it will never be where you are.

I think, secretly, most travel junkies would agree with this. I don't think I can deny it, but I've come to a similar realization. The problem though is that the idea is misguided. Holden says the thing one is after is happiness, which is a huge oversimplification. The search for happiness is a psychologized attempt to reinforce destination addiction by hinting that it was nowhere to be found in the first place. Happiness is a catch-all term for feeling good, feeling contented, but (as a great practitioner once told me) perhaps the search isn't for a way to feel good or better, but to feel more.

Robert Holden completely misses the mark on his definition. Perhaps it is not that one is unhappy, and therefore they need to look for a surrogate for their lack of happiness. Now, go back to the quote and replace the word “happiness” with “belonging.” Perhaps we can start to see what it is we are lacking. This thing we seem to be lacking is not something that can be psychologized. It is something that can't exist without other people, without each other. It is something that requires neighbours. Foundationally, it is something that requires community, which is inherently relational. Perhaps this is what so many westerners, whether zoo-viewing tourists or self-seeking backpackers are really pining for. Not happiness, not success, not even warmer weather or better pay, but the thing that acts as the most reciprocating foundation for all of the above — belonging and community.

Belonging and community are mutually exclusive. One can say “look around, this is my community” and have no clue how their neighbour across the street feels, or the name of the old guy who has lived ten-doors-down from them for a half century. Belonging can only exist when community is actively engaged, and community is only truly communal when belonging is felt and ritualized, and not just conceptualized. The reductionist, individualistic, western ideal and its historical impulse, from the monotheistic versions, to the scientific and psychologizing worldviews we see today. . . It is this historically cumulative process that has cut us off from each other and a sense of community, and thus belonging. It has segregated us to such an extent that we can come up with a definition such as “destination addiction,” but be entirely clueless about why it exists and how we choose define it.

Interculturality

Backpackers often come across with more intention and vigour in their desire to journey and learn than the typical package tourist. There is a tendency in the most progressive echelon of backpackers to want to learn from the cultures they encounter. But even the most progressive among us still tend to approach the other cultures in a similar fashion as their packaged counterparts, albeit in a more subtle way and often with more respect. It is not easy to break this cycle when people have inherited hundreds, if not thousands of years of culturally-entombed superiority complexes. At the Intercultural Institute in Montreal, Robert Vachon began to provide methods in which we can engage each other, as cultures and cultural beings, willing and open to be changed by, but not necessarily converted, by different perspectives.

Vachon speaks of interculturality as a skill to which we can engage with the cultural Other with an ever growing understanding of the historical, linguistic, and ritualistic ways in which we are limited in understanding the world. These limitations though, are not weaknesses, but strengths. They define our capacity, not only as persons, but as cultures to know that what we know about our world is limited, insofar as our tools – and in most cases this comes down to language – can inform us about the world. So, when we understand that many words, even concepts, cannot be easily translated into other languages and vice-versa, we can begin to see how vastly different other cultures' perspectives might actually be, and how their millennia-long cultural inheritances can limit them too.

If we are lucky, humbled, and honoured enough, it is here we will find ourselves in the presence of, and at the edges between other cultures. It is here, with an open heart, a concord (from French, meaning literally “hearts together”) and a willingness to be changed (but not converted), and with the requisite understanding of how truth, reality, and belonging has come to exist in western culture. And it is here that we might be able to undertake what has for many, up until this point, been a hazy, misunderstood glimmer of what engaged and entrusted travel might look like. Engaged by hearts and entrusted to descendents.

Through an intercultural dialogue and concord, we can begin to tell new stories.

Conclusion

The tourist's worldview seems fixed on and predicated by cultural and historical perspectives that prevent the western person from imagining their experience without a fence or glass between themselves and the cultural Other. This spectator mentality engages other cultures — in this case other peoples — with this idea that the cultural barrier is two-sided. It is not just glass, but a wall. In other words, the very arc of our separateness from other cultures, which is by default historical and linguistic, creates a zoo of the world, where everyone is set behind their own dividing lines and assumptions. Is it any surprise then that people build houses, not as homes, but as fortresses?

This isn’t to say that westerners' travel experiences aren’t valuable — of course they can be, but to what ends? To be able to say that they’ve checked off another notch on their “bucket list” — another commodified experience that will somehow create fulfilment where fulfilment is lacking? But therein lies the question: why would life be lacking fulfilment in the first place? It is as if someone intimated that you and yours are simply not good enough to begin with.

After a decade of backpacking and making all attempts to form travel into a transformative and redemptive homecoming, it's hard to say what I've accomplished in that regard. It has become increasingly obvious to me that centuries-old worldviews influence the way others, like myself, travelled and viewed the world. Worldviews based around cultural superiority that are seemingly dead. But the thing about assuming the dead are gone is that they we no longer recognize their presence, and what happens? They become ghosts. And the ghosts of these dead worldviews, the ghosts of the west's intellectual ancestors, the ghosts of Descartes and the early anthropologists, they are haunting us.

Perhaps now we can start to see how such a commodified, detached, and lonely culture could come to exist, as it has today. If the historical basis of the spectator mentality, which dare I say it, has even earlier implications, even older ghosts, can we begin to acknowledge why western travellers desire and necessitate souvenirs, and why memory might be a crucial part of the equation?

If we dig deep enough into this desire for exploration, whether culturally inherited (imperialist ancestry) or culturally consequential (homelessness), perhaps there we can dig our roots into a more visceral sense of belonging, one that isn't government sanctioned or inherited by amnesiacs. Perhaps we belong by our very virtue of being born into this world, into this planet, into each others arms and mutual indebtedness. But perhaps such a long and drawn-out misunderstanding of this very thing is what western culture teaches and embodies. When we live in a culture that says you do not belong, or does not offer up any ritual or remembrance for such an opportunity, for such a gift... if it does not offer you a chance to be grateful in order to give your gifts to that which sustains life itself, then what becomes of its people?

If we can begin with the patterns in early modern western history, which are still present, fuelling the surface of things, we can also start to recognize these patterns in our own lives and in today's global western culture. If we then find ourselves in the lands of other peoples and see these patterns clearly — these unspoken consequences of history and cultural amnesia, we can start to do so with an understanding of how things once were, still are, and can be. Through an intercultural dialogue and concord, we can begin to tell new stories. We can begin to forge narratives that our descendents can inherit without the spectre of being haunted by them, or haunting other cultures, in turn.

If we have these tools at our disposal, which include first and foremost the understanding that western culture has no greater lens for the world than any other, then maybe our desire to travel can be rooted in something more. To be rooted in that way, to be truly intercultural, to approach other cultures with a humbling concord of respect and conviviality might just lead us on our way home — towards or into a way of belonging that western people have not known for a very long time. With our tools firmly placed in both our hearts as well as in our minds, we might begin to envision what authentic travel, a communion perhaps, might look like.

CHRIS CHRISTOU is a freelance writer, chocolatier and tour guide from Toronto. Graduating from York University in Toronto in political science, he has spent most of the last decade travelling and working in the hospitality industry. Chris currently lives in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Add new comment