'My father would pull dead leaves from the basket and water the fern. It stayed alive for years.' [o]

MY MOTHER, who recently became a snowbird, leaves her home in rural northwest New Jersey once the leaves fall and trades oak and pine for sawgrass and palm. I spend the winter and spring living alone in the log house my father built. In winter, I watch snow clump on the branches of oak and maple trees and listen for the barred owl’s regular evening call as the golden sunlight slants through the trees. In spring, I prepare for my mother’s return, combing the yard for sticks and yanking weeds from the vegetable garden. I pull up fistfuls of purple dead nettle, shaking black dirt from their delicate roots and tossing them into buckets. I tug at tufts of grass and dandelions and squeal whenever an earthworm comes up, tangled in tendrils of root hairs.

Bending so I can reach underneath a wrought iron chair that sits in the garden, I stretch my arm to grab another handful of purple dead nettle and notice a small fern growing in the chair’s shade. The fern is made up of only one blade, and its pinnae are pale yellow. Ferns grow all over the forest just feet from the garden, but I’m surprised to find one growing here. I pull the purple dead nettle from the earth, but leave the fern where it is.

What romantic irony that such sex cells, in order to grow, should find each other in the shape of a heart.

When I was a child, my father brought ferns, tiger lilies, and hemlocks home from the forest. Most were planted outdoors, but a giant fern sat in a large basket on the top floor of our house, a balcony that opens to a cathedral ceiling and the living space below. Dry brown leaflets from the fern would fall and float to the main floor below. My father would pull dead leaves from the basket and water the fern. It stayed alive for years.

At a nearby ravine where he would take us hiking on weekends; there are more than 250 fern species, all in the wood fern family. I learned to identify Christmas fern, named because the plant remains green throughout the year and can therefore be used as decoration at Christmastime — but memorable because each tiny pinnae has a small hook at the base of one side, making it the shape of a tiny Christmas stocking. I learned cinnamon fern, whose chestnut-brown spore-bearing fronds sprout upright from the center of the plant. And I learned northern maidenhair fern, with its lacy leaflets and pink fiddleheads.

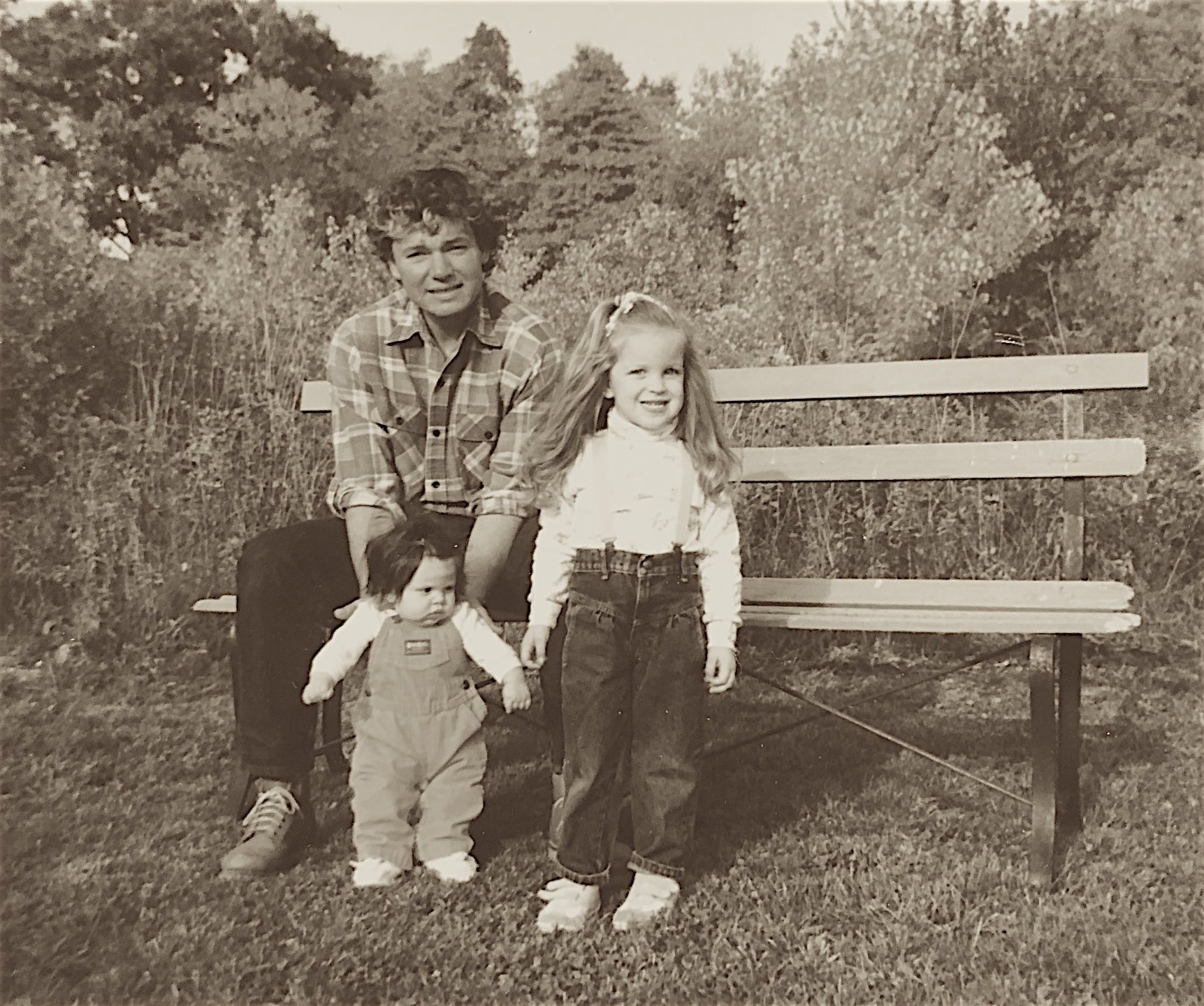

The author, her older sister, and a supervisor in their back yard.

My father brought ferns home from the forest because he loved green things. Our yard was small, but he planted trees there: Norway spruce, Douglas fir, blue spruce, and white pine. Rhododendrons bloomed in front of the house, and rabbits nested under a juniper bush. Our garden began as an unfenced patch of dirt where he grew asparagus and cherry tomatoes and zucchini. My mother wrote a poem for him, ‘On Being Loved by a Man with a Garden’

Romance, I plead. You

bring vegetables.

He grew broccoli, snow peas, tomatoes that she turned into sauce.

Under the sturgeon moon

I see your bent form hunting melons

and squash. The plumpest ones you give

to me. All summer, I’ll unwrap

leaves of lettuce and find heart.

The garden took a new shape when I was ten. My parents built an addition on the house, trusting an old friend to cut through the logs with a chainsaw to connect the old part of the house to the new. They put a fenced-in pool in the backyard, and my dad used the old logs to build raised beds within the fence, where he continued to grow vegetables that fed us through the summers. But he would only push seeds into the black dirt for a few more years.

'The cells unite over a film of water, then begin to grow into a new fern plant.' [o]

After my father died, my mother wondered what would become of the garden. She didn’t think she had the green thumb my father had, and to this day, she calls herself a half-assed gardener. But that first summer, she decided to plant the garden. Summer after summer, my mother learned how to make things grow, and I adopted my father’s love of all things green. I went to live in Australia and spent time in its tropical forests, where ferns covered the shaded ground, grew rootless on trunks of trees, and reached into the lower canopy. Tree ferns, perfect parasols of diaphanous leaf cover, stood ten, twenty feet tall. I would look up through their leaves — black lace umbrellas that let just the right amount of sun through to the damp ground — and search for their giant fiddleheads, uncurling from thick stipes.

Ferns appeared in the fossil record more than three hundred million years ago, the earliest vascular plant form and the most advanced of seedless plants, representing a middle ground between other seedless plants — algae, fungi, lichens, mosses, and liverworts — and the seeded plants that evolved next. Instead of seeds, ferns have spores: minute powdery units (brown, black, or yellow) that develop in small capsules that are released when ripe. Germinating in damp places, the spores grow into tiny, thin heart-shaped plants with male sex cells at the pointed end of the heart and female sex cells in small pockets in the notch of the heart. The cells unite over a film of water, then begin to grow into a new fern plant. What romantic irony that such sex cells, in order to grow, should find each other in the shape of a heart. Left with this image, it’s easy for me to associate love with this plant. I love that I can find it in ecosystems all over the world, in places as different as Australia’s tropical rainforests and New Jersey’s temperate hardwood forests, and that my father loved a particular fern enough to dig it up and tend it in our home for years.

The author with her father and big sister.

When my sister and brother and I left the house for college and then jobs, my mother decided to fill the pool in with dirt. One of the raised beds built from logs still stands in the shady part of the garden, but new raised beds fill the space where the pool once was, built with the help of friends. Those same friends planted a gingko tree just outside the garden fence: a tribute to my father. He admired the gingko trees planted along the avenues in New York City, where he went for chemotherapy. The leaves of the gingko reminded him of the tiny leaflets of a maidenhair fern.

A few days after discovering the fern in the garden, I go out to check on it. There is sunlight in the garden, and the crowns of trees are in that baby green state of no longer buds but not quite leaves. The fern has eight green leaves now, and a tiny fiddlehead sprouts from the middle of the plant, its curl smaller than the fingernail on my pinkie. I’ll come out in the mornings, and watch for it to unfurl. ≈ç

LINKS

FERN IDENTIFICATION. The RHS (Royal Horticultural Society) site provides detailed information about different types of ferns and other plants.

FERN FAN CLUB. The American Fern Society, established in 1893, has a site rich with information about ferns, lycophytes, and pteridophytes — plus many opportunities to gather resources, connect with others and even exchange spores. It is also the publisher of the American Fern Journal.

JENNA GERSIE is researching log cabins in American literature while studying for a PhD in English at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared, or are forthcoming, in Zoomorphic, About Place Journal, and The Fourth River. Jenna divides her time between the Rocky Mountains in Colorado and the Appalachian Mountains in New Jersey.

Snapshots courtesy of the author.

Add new comment