The beauty and 'terrible emptiness' of the Scottish Highlands. [o]

“We are affected strangely by any place from which the tide of life has ebbed.” So wrote Neil Gunn, the early twentieth century Scottish novelist, speaking to his biographers, F.H. Hart and J. B. Pick, and quoted in their book, Neil Gunn: A Highland Life (1981). He was recollecting the terrible emptiness of the Scottish Highlands that had been purged of humanity, often violently, during the nineteenth-century clearances, when absentee landlords judged there was more profit in sheep than leasing their land to populous communities who had practiced mixed farming for centuries past.

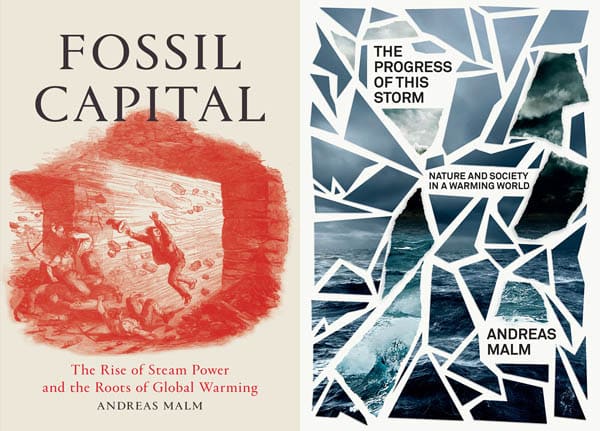

In the wildlands of California, across the deserts, mountains and plains, it is this echoing sense of desolation that prevails — where humans are no longer present amidst the rich flora and fauna of the state’s varied ecosystems. Corralled in massively polluted conurbations connected by ribbons of freeways and their associated services, products of what Andreas Malm characterizes as ‘fossil capital’, Californians are effectively exiled from the spaces between. Only the two-lane, black-top state highways snake into these largely forgotten areas, away from the cities that once supported homesteaders and small farmers. In these spaces, Big Ag and Big Oil now predominate, employing scant permanent personnel and relying instead on independent contractors and seasonal labor.

We should not regret that America never possessed a peasant class, but might note they were connected to the land, capable of a degree of self-sufficiency, and economically conscious.

While agriculture attracts vast influxes of immigrant field workers who drive to the fields from surrounding small towns or follow the harvests up and down the state, these workers do not experience inhabitation. Theirs is a casual occupation of places in which they are temporarily housed — and meagerly rewarded. We should not regret that America never possessed a peasant class, but we might note that, despite their global exploitation, they were (and in places remain) connected to the land, capable of a degree of self-sufficiency; and, they were economically conscious. Not so the pools of labor that now well up on demand across the state, as corporate profits dictate.

Oil service workers contract to drill, perform ‘workovers’, and transport oil and produced ‘waste’ water for a complex of financially intertwined oil lease-holders and owners. These workers are essentially itinerant journeymen, often lacking a geographic locus. In Southern California, the oil industry has been largely exiled to the hinterlands where, abetted by the Federal Bureau of Land Management, it can drill with comparative impunity.

The Blythe Intaglios were geoglyphs first noticed by a US military pilot flying over the California desert in 1931. [o]

In the West, we had, until the middle of the last century, a homesteading culture. In Southern California’s wild places — like the Mojave, Anza Borrego or the Carrizo Plain — remnants of that culture’s buildings are preserved in the dry air: wood, iron and corrugated sheet metal glowing in colors of dark browns and rust reds amidst the desert scrub. In these places, on boulders and scattered over the thin soil, there is evidence of far older, indigenous cultures. Here, Native Americans fashioned stone tools, left lithic scatter (stone shards from shaped rock) and created pictographs, petroglyphs and, more rarely, geoglyph alignments. Their reed and timber shelters are scattered to the winds, their baskets stolen long ago, and their food resources evidenced only by piles of bone and shell fragments (middens). But these cultures endure in the marks they left on the land.

On the Carrizo Plain, where I camped during the last full moon, farmers abandoned their combine harvesters and other agricultural equipment in the 1940’s when winter rains grew less reliable and wheat could no longer be profitably farmed. At approximately the same time, the sand cranes ceased over-wintering on the plains as their marshes disappeared. In his Marshland Elegy (1937), Aldo Leopold writes of the crane, “. . . his tribe we now know, stems out of the remote Eocene . . . Their return is the clicking of the geologic clock.” On the Carrizo Plain, where there were once crane marshes, there are now salt flats. The ineffable return of ancient birds is forever foreclosed.

Andreas Malm: 'Without a mass movement we don't stand a chance against fossil capital'. [o]

The area is named after the rushes that grew in the wetlands, but they too are long gone. Cattle ranching was the final strategy of failing farmers, but their buildings, barns and cattle pens today lay picturesquely abandoned along the foothills to the west. The Carrizo Plain has been relinquished as a place of human habitation while the Tule Elk, coyotes, and jack-rabbits endure, still finding summer water at the remaining springs. Tourists visit from surrounding cities and their suburbs when the native wild-flowers are in bloom, but these are only deemed worth seeing after a particularly wet winter season. In 2017, thousands drove over deeply pot-holed, mostly dirt roads to view the flowers each weekend in March and April. Many remained in their cars, the vistas framed in their windshields or captured on the screens of outstretched arms clutching cell phones.

Across the world, urban dwellers have been alienated from the wildlands that surround them. A little more than two centuries ago, only two percent of the Earth’s population lived in cities. We are fast approaching a time when most do. Here in America, we have been lashed to what Stephen Jay Gould calls ‘time’s arrow’ since the country’s inception in an embrace of innovation and industrialization. (Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time [1987]). Gould’s countervailing notion of time’s cycle never stood a chance — Jeffersonian democracy was swept away in a flood of consumer- (and necessarily urban) based capitalism. Progress trumped the rhythmic verities of an agrarian life. Though agriculture is now mostly pursued with an industrial-age ideology — hence, factory farming and alienated low-wage workers — Jefferson’s ideal of homesteaders morphing into yeoman farmers (as was often the pattern in the Scottish Highlands before the nineteenth century) was never realized in a society more interested in material prosperity than rural quietude.

They were co-creators of their world, not its destroyers.

There has been intensive economic exploitation of the rural hinterlands, but rarely does it produce stable levels of human habitation. Lands have been raped and pillaged, logged, drilled and strip-mined. Once their indigenous occupants had been removed, they were often left abandoned, untended, and empty — ready to become invented wildernesses subject to a romantic narrative that proclaims them inhospitable and anathema to human presence. We have been driven out of these lands because of false narratives that support an urban civilization powered by fossil biomass where, ironically, we are increasingly dependent for our sanity on the non-indigenous animals we call our pets — and perhaps a backyard garden of exotic vegetation, raised vegetable beds or a few potted, exogenous plants.

In Britain, George Monbiot and others have urged that top predators be re-introduced to the countryside. In the US, there have long been successful moves to reintroduce wolves to wilderness areas. Yellowstone’s wolves have had a startlingly benign impact by rebalancing the park’s ecosystem. In the Santa Monica Mountains, a dwindling population of mountain lions are carefully tracked and protected.

All the while, we are becoming increasingly cognizant of the great damage we have done to the planet. A new report from the World Wildlife Federation claims that humanity has destroyed sixty percent of the planet’s wild mammals, birds, fish and reptiles since 1970. It may be time to consider the measured re-introduction of our own species into the wild in a last ditch effort to re-discover the circumstances of sustainable co-habitation with non-human life-forms.

Releasing a Sawtooth wolf pup into an acclimation pen in Yellowstone Park, February 1997. [o]

In California, Spanish and then Anglo-American imperialists destroyed what Benjamin Madley in An American Genocide (2016) described as “an exuberant clamor of Native American economies, languages, tribes and individuals”. Instead of domesticating wild animals, these cultures managed their environment to facilitate hunting. Instead of practicing agriculture, they enabled the edible plants, seeds and roots that made up much of their diet to flourish by weeding, pruning and, most of all, burning. They were co-creators of their world, not its destroyers. Is it overly romantic to imagine that the early homesteaders, despite their genocidal tendencies with regard to the native population they displaced, still retained a sense of connection to the land — and remained linked to their peasant forebears, generations apart and an ocean distant?

If, as Frederic Jameson has remarked, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism,” then the World Wildlife Federation report has facilitated the first part of that heuristic exercise. Can we imagine a rewilding of humanity that entirely forestalls our economic predations? Can we embrace time’s cycle as the dominant metaphor in our brief lives?

Can we, at last, begin to believe that modern humans can live in the wild and truly prosper amidst its natural beneficence? ō

LINKS

A video of a lecture by Benjamin Madley, author of An American Genocide.

This article from these pages, 'In the Embrace Wolves', follows a classic literary theme fundamental to our own explorations: that which occurs when the human and non-human coexist.

JOHN DAVIS is a California-based architect "living on too many acres of chaparral in Upper Ojai." He writes a blog, Urban Wildland, where he says his writing "is a way of resolving the values it represents; a single voice, yes, but one that is, I hope, always evolving."

Comments

" Is it overly romantic to

"Is it overly romantic to imagine that the early homesteaders, despite their genocidal tendencies with regard to the native population they displaced, still retained a sense of connection to the land — and remained linked to their peasant forebears, generations apart and an ocean distant?"

Sadly, I'm afraid it is. It is not possible to be selectively genocidal.

Add new comment