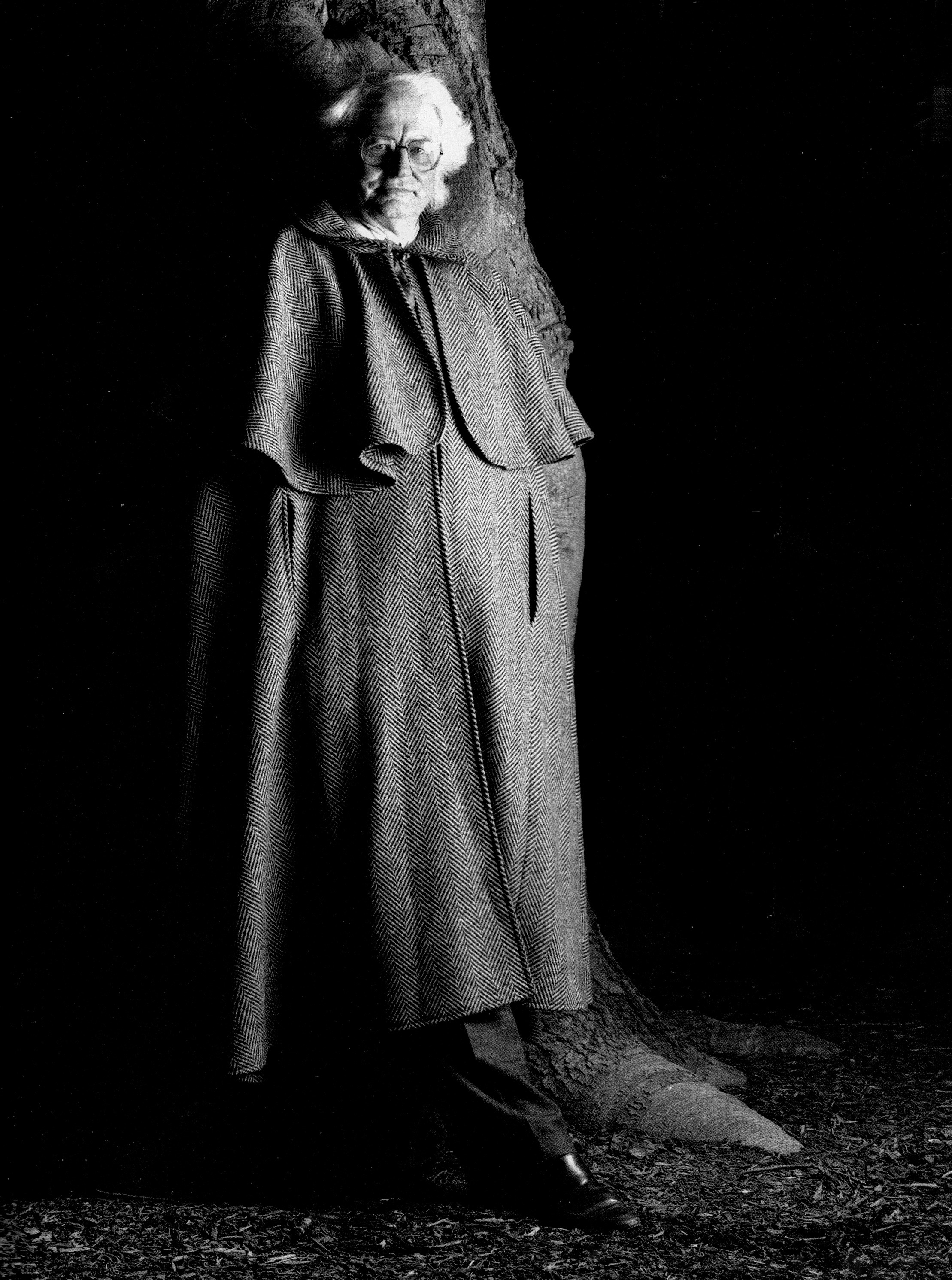

A Minnesota man. [Photo by Greg Booth.]

1

It’s a radiant Spring morning in May, 1997. Robert Bly, a giant in American poetry, is sitting in a palatial garden in Fes, Morocco where we’ve both come to attend a Festival of World Sacred Music. We had met a decade earlier at one of his famous men’s gatherings in Minnesota, a week devoted to “passion and purpose in the male psyche.” A masterful teacher of poetry, Bly had begun by teaching us the poems of William Blake.

(You can sample some of that teaching, and get a taste of the men’s work for which Robert Bly is almost as well known, in the transcript excerpt that follows.)

Sitting now in a Moroccan garden, with the ever-present swifts of Fes flying over our heads, Robert is telling me about Morningoems, a new collection of his — and offering some practical advice on how to follow ‘flyaway thoughts.'

3

BLY ON THE 'WILD MAN'

Here is a taste of the men’s gathering in 1988 where Robert Bly and I first met. It's taken from the radio documentary I made of the event. This being in the days before publication of his bestselling book Iron John, the word 'wild' was often being taken to mean 'violent,' so Robert asked me to rename the program, from 'The Wild Man' to “Men and the Wild Child”

BLY The Wild Man is normally discussed during our conferences in relation to five other ’Joys’ of men: the king, the warrior, the trickster, the lover, and the quester. All of these represent possibilities that a man may develop. After age 35, it seems that the time comes to live these joys consciously. A man may look, for example, at how much genuine king he has in his life. Ordinarily, if he allows other people to initiate a project, or thought, or system, then he doesn’t have much king. During this particular conference we’ll concentrate on the ashamed, angry, or disappointed little boy who acts usually to block the expression or development of any one of these Joys. Similarly, women sense that the disappointed or ashamed little girl in them can block the development of their queen or wild woman, or female warrior, and so on.

We’re going to begin by learning a little Blake poem, 'Infant Sorrow.' Are you ready for this?

My mother groan’d! my father wept.

Into the dangerous world I leapt.

Your mother’s groaning in the beginning is proper, isn’t it — to begin with that? Then it goes to the father, and what the father does is weep. Part of that is from the tradition that your soul came from another place. lt was dry up there, and here it’s wet. The tradition is that when you come down here, you put on a watery envelope that’s called the body. Your father was in touch with that spiritual world; he came from there himself. And when your mother groaned, she was not in touch with it. But he was, and he weeps that you were born at all. Is that clear? Let’s continue:

Helpless, naked, piping loud:

Like a fiend hid in a cloud.

The ‘fiend’ is the wild little soul, hidden in the cloud of the body. So this is not Hallmark sentimentality about a little baby. This boy is dangerous, from the first moment he’s born. But he’s bound, too.

Struggling in my father’s hands,

Striving against my swaddling bands,

Bound and weary I thought best

To sulk upon my mother’s breast.

Now that’s a genius poem. l don’t know how many times I’m in that mood, and I think, everything considered, the most rational thing to do is just to sulk: not answer my wife, just sulk. Is that right? So, one way you can think about that is, ‘Who is it in me that’s doing the thinking? There’s an adult in you doing it, when you’re lucky. And then, more and more, I’m aware of a three-year old in me. He never got beyond three. He makes up his mind by then that the world is a hostile and strange place. And he holds on to that opinion, often against the evidence, so that when the 35 year-old wants to change his life, to break out, he gets fouled up by the kid inside who’s still brooding about the birthday party that didn’t work out. The same three-year-old rears his head disastrously in arguments with women. Your exercise here is to write down the conclusions that that child came to when he was faced with death. Sentences like: ‘It is better' to pretend I am not who I am than to die.’ ‘Better to be unmanly or unheroic, and to sulk rather than to lose the mothers breast entirely. Or, ‘It’s better to get sick than to go out into the world and die.’ The child in us is so strong that he may actually control the body and health. In my case, the three year-old would give me a sore throat and a fever two days before I had to give a poetry reading. What’s required for men is that we hear that child and listen to him. Tell the little boy that he’s made up his mind on the basis of inadequate information. Name his fear. Talk to him. In my case I said, ‘Listen, I went to California in 1956, I was there for six days, I didn’t die. I went to New Jersey-remember that time? — in 1961. It was New Jersey, I still didn’t die.’ I went through a whole series, and said to him, ‘Where were you when these things happened? I did not die. I’m alive right now.’ And it was interesting, because he hadn’t really heard about it. And I was astounded. Within ten minutes, my throat was fine, and my fever was completely gone. That was a lesson to me. I just could not believe that.

[You can hear the whole of Tim Wilson’s CBC Radio Ideas program about that Minnesota Men’s conference here.]

Bly in the 1950s in Minnesota. [o]

4

There’s an epigraph to that spirited conversation Bly and I had about things left to do in life. Two decades after I recorded him for radio program, I was lying in a hospital bed, with the doctors were telling my 8-months pregnant partner that I might not make it through the night. The phone rang, and it was Robert. He told me, just as he did on that morning in Morocco, "you know, your soul doesn't mind leaving here." I wheezed back, "but, Robert, there's another child coming!" And he said, in that lovely untamed voice of his, "Ok, well you'd better stick around.” In great good fortune, I was able to.

And then, just yesterday, as I sought some of his words to express my own sorrow at his passing, I came across this poem in his book.

A POEM IS SOME REMEMBERING

It’s morning; there’s lamplight, and the room is still.

All night as we slept, memory flowed

Onto the brain shore. Memories rise and fall

And leave behind a delicate openness to death.

Almost a longing to die. That longing

Is like rain on canyon ground, only droplets.

And the brain is like brown sand, it stretches

On and on, and it absorbs the rain.

What is a poem? “Oh it is some remembering,”

A woman said to me. “Thousands of years ago,

When I stood by a grave, a woman handed

Me a small bone made red with ochre.

“It was a poem about heaven, and I wept so.”

[From Morning Poems, Robert Bly, Harper and Collins, 1997.]

Portrait of Robert Bly by Millicent Harvey from The Family Therapy Networker, May/June 1990.

LINKS

ROBERT BLY: A THOUSAND YEARS OF JOY. A film portrait that traces Bly in his singular path from Minnesota farmer’s son to anti-Vietnam War activist, to instigator and mentor of the 1990s men’s movement. He was one of the first to translate Pablo Neruda and Rumi, and his work with Joseph Campbell led to the unexpected pop culture phenomenon of Iron John. Director: Haydn Reiss (US 2015) 60 min. Watch here.

ROBERTBLY.COM >

THE POET'S FOUNDATION: ARTICLE ON ROBERT BLY >

BIOGRAPHICAL ARTICLE: 'Rays of Distant Bly Light from a Rare Stellar Convergence,'

by Mark Gustafon, Michigan Quarterly Review (2015) >

THE MINNESOTA MEN"S CONFERENCE >

TIM WILSON is a documentary filmmaker, radio producer, essayist and photographer. He has interviewed many notable figures of our time. Of particular relevance to this interview is his feature documentary, Griefwalker (The National Film Board of Canada, 2008), about a man who turns the act of dying into an essential part of life. Tim lives in Bear River, Nova Scotia. View his site.

Comments

Thank you Tim for this…

Thank you Tim for this reflection and for Bly's words from so long ago, as if we can hear him now in a room with us, being honest and direct while sounding like an incantation.

Thanks for the link to the portrait doc on PBS. It is rich with poetry and a wonderful cast of important poets -- one only wishes there was more time to hear more from them too, Gary Snyder et al. But there is a lot of Robert in it, and plenty of poetry, rare enough in a TV show.

Add new comment