The author and the rest of the Peace Corps trainees in his group pictured outside of Zapata, Texas, near the border with Mexico in 1967. David is on the top row, third from the right.

How to Win Friends and Avoid Sacred Cows

by David Macaray

The Ardent Writer Press, 2016

I first took notice of the writer/playwright/labor reporter Dave Macaray when CounterPunch ran his pokerfaced report on the vagaries of the manufacture of toilet paper, which I found to be hilarious. And which, against all odds, managed to throw a ground-breaking, figure-ground diagram over this well-known, well-used, well-appreciated item that tore away the veil normally shrouding its mention. I requested the author's email for the purpose of praising him, and Macaray and I began an occasional back-and-forth that has now spanned a number of years.

When I got word that his book How to Win Friends and Avoid Sacred Cows had come out, my fingers sped to the only internet site from which I can get books sent from the northern imperium south to the altiplano. To tell the truth, the title didn't draw me in. Nor did the topic: his stint in the Peace Corps in India in 1967-68; I was busy reading books about German concentration camps and Latin American dictatorships. But finally I got around to it.

My humble lesson: Don't Judge a Book by Its Title.

The double date at the Taj Mahal. The non-stop inquiries about who killed JFK. Each story arrives as a surprise . . .

Macaray's style of simple, diary-like documentation of everyday events that took place during Peace Corps training and throughout his two-year experience of India belies the reality that his topic is far more profound. His literary achievement is nothing less than a slide down the razor's edge of one of history's most pressing social issues: cross-cultural sensibility. Much to the amazement of the young idealists who were sent to the subcontinent, little-to-no work actually took place. As Macaray writes:

From the onset, we sensed a serious disconnect. Because we were self-conscious of the fact our Indian Peace Corps experience didn´t seem to correspond to those inspirational stories we'd all heard—those bracing accounts of heroic PCVs (Peace Corps Volunteers) stationed in Africa and Central America logging prodigious hours doing noble work—we were constantly battling a nagging sense of “failure.”

By his own report, it appears that during his total time in the Peace Corps our author did not build more than a small number of deep-bore water wells, each of which took something in the ballpark of three or four days. Lacking anything to do that even vaguely sounded like the humanitarian mission he had signed up for, he made do with what was: a tonnage of free time; the never-ending education that India offered to a 22-year old who, just months before, had been flipping hamburgers in a fast-food joint in southern California; and the perennial eruptions of dysentery-of-a-bacillary-assortment in a country—dare I say it?—dangerously low on toilet paper.

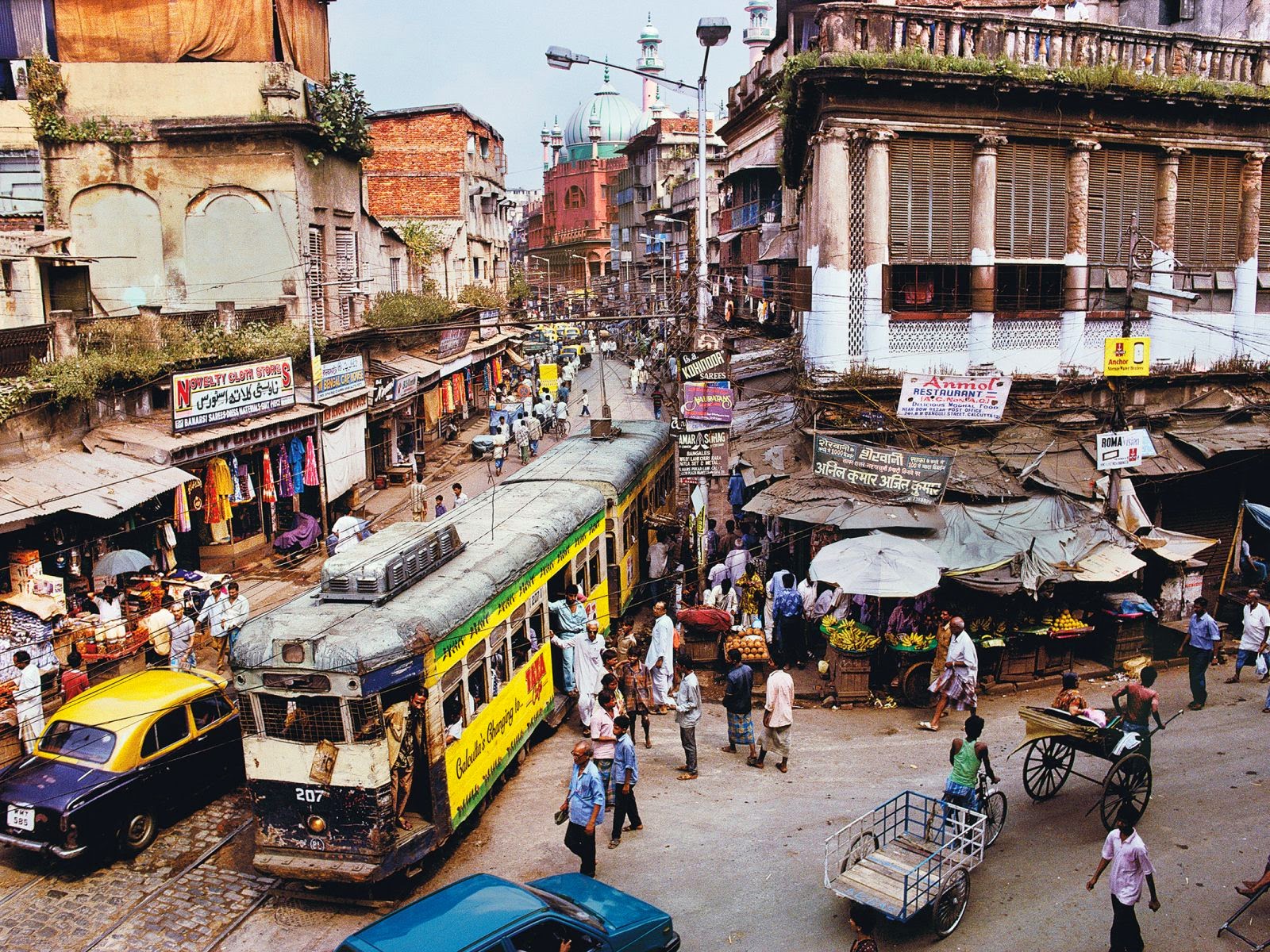

Calcutta, now Kolkata, in the 1960s. [o]

Global Moments abounded—meaning those unfortunate, and either humiliating or hilarious, frictions that have been made manifest by millennia of imperial pursuits.

I rather like Macaray's account of the time he went to a Calcutta nightclub and, a mere five years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, was directed to a table occupied by four inebriated . . . Soviet . . . sailors. Said adversaries burst into a table-pounding rendition of “Amrika!! Amrika!!”—all the while the cabaret singer was belting out “Happy Birthday to You/You Belong in a Zoo/. . .”, sauntering about and gyrating her hips as the men in the audience hurled rupees at her.

Then there was the occasion when the police in the small town of Malerkotla pulled his bicycle over to give him a palm reading. Or the day he hired the town midget to perform a massage, rode the fellow for all to see on the handlebars of a bike to his house; the townspeople heckled and hooted due to the going rumor that the little man's real business was sexual favors. And, lest I forget, the 30-minute speech our protagonist was called upon to deliver at the local university on the . . . American Electoral College. The wild-boar hunt the chief-of-police invited him to attend. The time he accidentally ventured into the women's quarters of a local house. The double date at the Taj Mahal. The non-stop inquiries about who killed JFK. Each story arrives as a surprise, compels one to stay up too late reading, and, needless to say, is always punctuated by a glass of tea with sugar and milk.

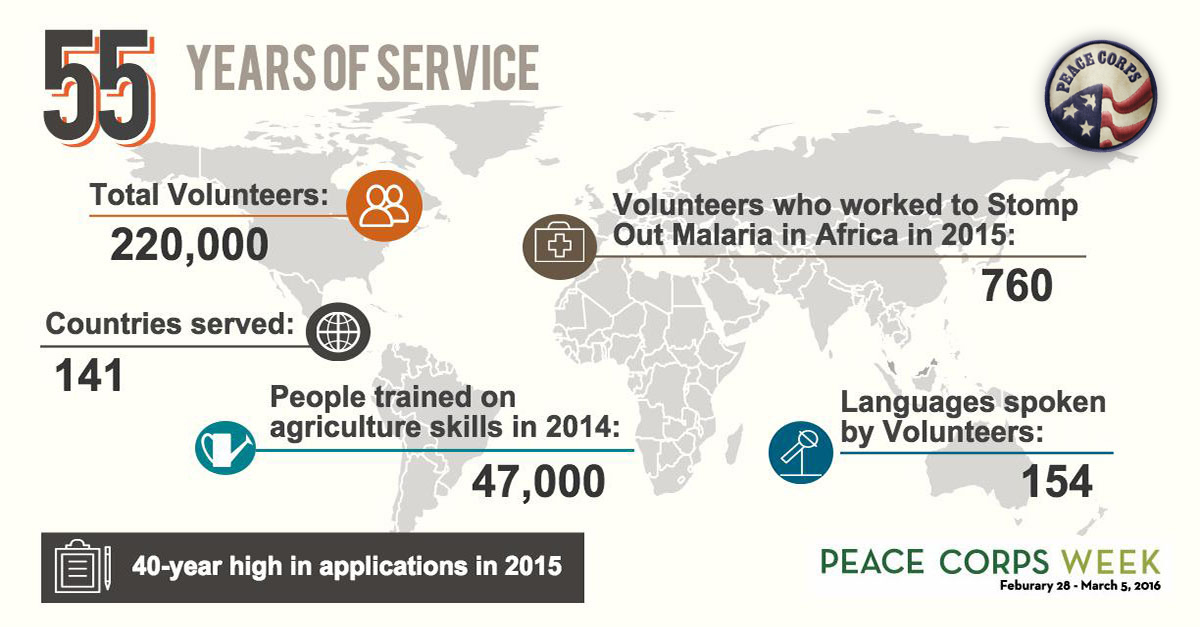

John F. Kennedy's Peace Corps, a policy off-shoot of the Marshall Plan, captured the imagination of the U.S. public; after its creation thousands of letters poured into Washington from young Americans hoping to volunteer. [o]

Recent Peace Corps infographic . . . Signs of profuctivity abound, though not so much in India in the 60s. [o]

Macary tells his tales in such a down-home way that, by book's end, I had the feeling that I myself had been in the Peace Corps: seeing, smelling, tasting, listening to, and making an ass of myself in India. Curiously, unexpectedly, I now know much more about the country's history, its problems, its cultures, its passions, its conflicts, its sense of humor, and its foods than I ever did from reading books, watching movies, viewing Indian art, or hanging out with Gandhi-ophiles in anti-war/pacifist movements.

And true to the power of any good book, Macaray's inviting writing style has caused me to reflect on my own experiences—both humiliating and hilarious—as a border-crosser into cultures other than those I grew up in. ≈©

Sadhus in India. Looking into the eyes of other cultures . . . what do we see? [o]

CHELLIS GLENDINNING is a psychologist, an editor of The Journal of Wild Culture, and the author of seven nonfiction books, many essays and articles, a poetry chapbook, and a folk opera in Spanglish. Her first novel, Las relaciones de objetos/Object Relations, will be published in Bolivia in 2018. A U.S. citizen, she lives in Chuquisaca, Bolivia. www.chellisglendinning.org

Macaray on a houseboat in Srinigar, Kashmir in 1968.

Comments

Thank you so much for that

Thank you so much for that very thoughtful and comprehensive review. Reading your comments, and reminding me of those two amazing years, actually revived some poignant memories for me.

Add new comment