If you're wondering if the cats in your neighbourhood actually have such a significant effect on the bird population as reported, consider the recent news from the Galápagos Islands. Birds species that Darwin catalogued on his historic fact-finding journeys, not seen since that time, have mysteriously reappeared.

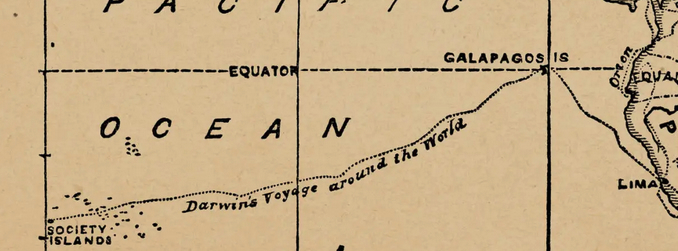

As a young naturalist, Darwin first set sail on HMS Beagle in 1831, full of anticipation for his voyage around the world. By the time he reached the remote shores of the Galápagos Islands in September 1835, his first impressions were less than enthusiastic.

“Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance," he wrote in his journal. "We fancied even that the bushes smelt unpleasantly." Upon further investigation, Darwin soon began to discover aspects of the South American islands that fascinated him, prompting him to declare: “The natural history of this archipelago is very remarkable: it seems to be a little world within itself.”

Darwin noticed that some of the birds differed slightly in size, beak shape and markings, while still closely resembling others that he had seen in South America.

He described the islands as being “a favourite resort of buccaneers and traders, who found an ample supply of food in the large tortoises which abound there; and to these visits we may perhaps trace the introduction of some animals whose presence it is otherwise difficult to account for.” (His description of the islands takes up a chapter of his book The Voyage of the Beagle.) Little did he realize at the time how these imported animals would affect the future of the species he was cataloguing.

The species prominently affected by these non-native predators were some of Darwin favourites, finches and mockingbirds, or as he called them, mocking-thrushes. What's relevant about these birds is how they helped Darwin come up with his theory of evolution.

For instance, mockingbirds were given their name due to their skill in mimicking the calls of insects, amphibians and other birds. None of the Galápagos mockingbirds do this, but they do have a series of distinctive calls which they use under different circumstances. Darwin noticed that the birds differed slightly in size, beak shape and markings, while still closely resembling others that he had seen in South America.

“The more distinct species," he observed, "as the mocking-thrushes (Mimus), the tyrant fly-catchers (Pyrocephalus and Myiarchus), and the ground dove (Zenaida), are all allied to nonmigratory species peculiar to tropical America.”

He made detailed sketches of the Galápagos finches — now commonly known as Darwin’s finches — and realized that the size and shape of their beaks depended on the kind of food they preferred: either seeds, plants or insects. The way birds had adapted to their environment held the key to his understanding of evolutionary biology.

Illustration of the Galápagos rail (L. spilonota) by Thomas Bell who accompanied Darwin on the voyage of HMS Beagle.

On the island of Floreana during his visit to the Galápagos, Darwin recorded the presence of the bird called the Galápagos rail (Laterallus spilonota) — also known as the Galápagos crake or Darwin's rail — which is practically flightless and therefore particularly vulnerable to predators.

Of all the islands in the archipelago, Floreana had been the most dramatically altered by human activity. Its abundant resources, including easily accessible sources of fresh water, made it attractive to seafarers who used it as a convenient stopover where they could pick up supplies. As well as cats and rats, they introduced cattle, goats and donkeys to the island.

The Floreana Ecological Restoration Project aims to redress the ecological balance by removing invasive animals and plants, allowing native species to thrive. The project is led by Galápagos National Park Directorate and carried out by Jocotoco, Island Conservation, the Charles Darwin Foundation and their partners. In 2023, after ten years work, rats and feral cats have mostly been eradicated.

Over the next few years, there are plans to introduce 12 species that have disappeared from the island since Darwin’s visit. As well as 10 species of birds, including the Vermilion Flycatcher and the Floreana Mockingbird, Giant tortoises will also be re-introduced, either from breeding programs or from other islands where they have survived.

Giant tortoises commonly live over 100 years, some living up to 175–200 years, with a shell length exceeding 5 feet (1.5 meters) and weighing up to 550 lbs (250 kg). [o]

The Galapagos rail has made a remarkable comeback on Floreana, with sightings confirmed for the first time in 190 years, and its presence has now been recorded by researchers in three different locations.

With predators almost eradicated, finches on Floreana have a new-found confidence and are trading songs with other birds. Some have even started singing completely new songs, which have been recorded by researchers. Almost 200 years after his visit to the island, Darwin’s legacy lives on in this type of nature conservation work.

After returning to England from South America, Darwin continued to work on his theory of evolution by natural selection for many years before publishing his ground-breaking book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection in 1859. The book was highly controversial at the time, sparking the “1860 Oxford evolution debate” – a series of lectures about the scientific evidence for evolution [see video representation below].

Darwin spent the last 40 years of his life in Down House in Kent, South-East England, which is now an English Heritage property open to the public. His life’s work and achievements are celebrated on Darwin Day https://darwinday.org/ which is held annually on his birthday, 12th February. Interestingly, though Darwin died at 78 in 1882 — almost 150 years ago — we still live in a world where some people dispute his findings, particularly in some conservative religious communities in the United States. ≈ç

ANGELA LORD is the Nature Editor of the Journal of the Wild Culture. Originally from South Yorkshire, England, she studied Modern Languages, then gravitated print journalism as a news reporter and feature writer. She is now a freelance writer based in Surrey, UK.

Add new comment