TRAVERSE CITY, MICHIGAN — Few things could be more crucial than our aim to return the fate of nature to the center of economics and decision-making. That’s the Land Ethic, and it was expressed with particular force and clarity in Aldo Leopold’s timeless Sand County Almanac

Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

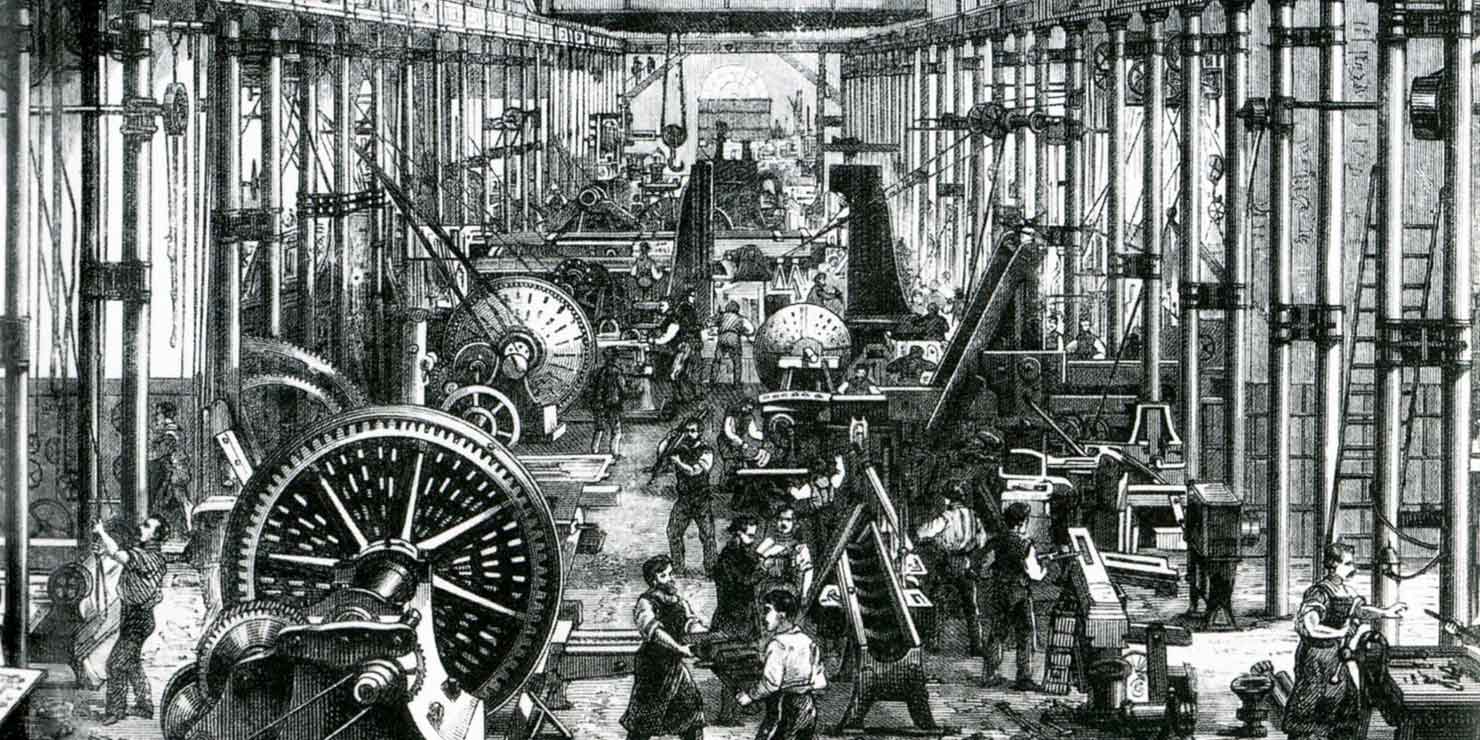

All consumerism, electronic or other, usually violates the Land Ethic’s every tenet, starting with the injunction to question. Mass-produced goods tend to distance consumers from the truth that raw materials were once some other being’s home or sustenance.

For all its infatuation with cognition, much of what the InfoTech industry generates seems mindless. It’s an enthusiastic spew of haste, complication and craving. Most of its products are solutions in search of problems, or solutions to the problems inherent in its products and the disruptions they cause.

To argue that the solution to a technologically spawned problem might be to part with the technology rather than accommodate the world to it is deemed unrealistic. Yet as the saying goes, when you find yourself in a hole, it’s best to quit digging.

The Luddites’ were originally concerned about “machinery hurtful to the commonality."

There are essential qualities of attention and relationship — within our own species and with the living world — being swamped by electronic media and instantaneous communication. There’s damage and disconnection resulting from all that connectivity.

Nowadays casual users show you pictures, demonstrate apps and are glad to be in frequent touch with the grandkids. Amnesiac, they never had or forget to miss the habits and tastes displaced by Silicon Valley surfeit. If you couldn’t have photographed that flower on the nature walk, you might have drawn it or collected and pressed it. If you possessed only one image of your grandchild, you would keep it in a golden locket. If you received in your mailbox just one letter a month from your sweetheart overseas, you would reread it until the pages became velvety and you knew the words by heart.

We suppose that adoption of information technology is a one-way trip. Habituated, we can’t live without it. We just have to accept the detriments, like depersonalization and annihilation of privacy. At the very least we might consider deliberately withdrawing from cyber technology’s sphere of influence, for the sake of cultivating vital relationships with our biotic communities.

In 1867, Karl Marx referred to the Luddites in Capital: Volume I, noting that it would be some time before workers were able to distinguish between the machines themselves and "the form of society which utilizes these instruments.”

Leopold spoke of having “an intense consciousness of land.” Such consciousness would counter techno-utopianism. In the patches, large and small, of what Arne Naess called free nature, utopia is irrelevant. If you exercise your inborn awareness, you’re in Paradise. And in the places that have been trashed by human purposes, the obvious need is for care and hands-on attention, reclamation and restoration, not sci-fi technology. Land is alive and actual. Cyberspace is notional, no place at all.

“Our educational and economic system,” wrote Leopold in 1949, “is headed away from, rather than toward, an intense consciousness of land. Your true modern is separated from the land by many middlemen, and by innumerable physical gadgets. He has no vital relation to it . . .”

Rapt attention can’t be in two places at once. The distractions afforded by information technology may not be compatible with a vital relation to land.

At sixty-six, with at least two-thirds of my life behind me and time fleeting, the question of what I want to pay attention to is basic. Electronic screens and all they bring are low on the list. Trees and their associates are near the top. My everyday life unfolds in a woodburb in Northwest Lower Michigan. It’s a pretty pastoral landscape dotted with single-family dwellings. Daily walking in this farmed and wooded country is as vital to me as food and friendship. Especially at the peak of fall color even third-growth woods can be rapturous. On a recent walk I realized that I might not need to visit Chartres or Sainte-Chapelle because the sun — incandescent in gold, scarlet, vermilion, citron, burgundy, yellow, saffron and crimson foliage — and the somber trunks, branches and boughs of maple, basswood, poplar, ash, and hemlock, were cathedral enough.

They had to be supple and curious, but conservative. Disruption was not among the behaviors that conduced to survival.

Rich as the moment was, there was an inescapable sadness. Most of the ash trees in our woods are dying or dead. The proximate cause of their mortality is an insect, the emerald ash borer, which arrived a few years ago, courtesy of world trade. The sugar maples and the beech trees also are diseased and dying. Multiple factors, climate chaos among them, are involved. The hardwood forest I love today will be driven north, or to oblivion.

Our Paleolithic ancestors, whose lifeway has had the greatest longevity to date, were integral and adapted to their bioregions. They had to be supple and curious, but they also had to be conservative. Disruption was not among the behaviors that conduced to survival. Through the modern and industrial eras, disruption of all our relations and all our bioregions has been accelerating to this climax of globalization.

Digital technologies are just the latest wave of inventions to trigger diasporas of place-based communities, helping overthrow what Stewart Brand called “the tyranny of geography.” While information technologies beglamoured our attention, and the vested interests prospering by them agitated for more coding and STEM courses in the curricula, half the wildlife in the world was annihilated.

Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley’s NewSpeak, disruption becomes a virtue. The juvenile nihilism in this exaltation of the new and dismissal of the old is pretty much the way I thought when I was in my 20s, although what we were after back then was Ecotopia, not the Singularity. So I confess my nostalgia for the days before our minds and daily lives were herded online. Less could be more. You couldn’t claim a multitude of relationships and you usually knew which borough or bioregion the people you dealt with were coming from. I miss the olden days of respect for time and distance.

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) was an American author, scientist, ecologist, forester, conservationist and environmentalist who was influential in the development of modern environmental ethics and in the movement for wilderness conservation.

Information technologies now intrude on the integrity of the most personal human activities, like contemplation, courtship, intergenerational communication, and education, finding in them all marketing opportunities.

Audre Lord’s aphorism about the ends and means of social change — that you can’t use the master’s tools to tear down the master’s house — reminds us that all technologies, even the ones we’d like to employ in the world-saving, public intellectual biz, have both political and ecological consequences. What one person regards as “machinery hurtful to the commonality,” which was the original Luddites’ concern, may be another’s appropriate, renewable, green, or strategically indispensable technology. These are contradictions we must contend with.

Not uniquely, information technology’s manufacture is often outsourced to sweatshops; and it requires toxic chemicals and brutally extracted resources. When the latest device becomes obsolete or breaks, it’s a poison Apple: e waste, problematic to dispose of. The technology is increasingly wireless, and whether we utilize wireless devices or not, their EMF emissions are nearly impossible to avoid, wreaking neurological and biological misery.

All that etheric connectivity runs on hydro, coal, gas, nuclear — and a smidgen of renewable energy. Worldwide Internet electricity use was 210 billion kilowatt hours around 2010. Author Jane Ann Morris has wryly calculated that two billion bicycle generators being pedaled by eight billion pedalers working six-hour shifts round the clock could meet that demand in a very eco-friendly way.

No technology can instill compassion or courage in a human heart. When we sideline the devices, we face Life with a capital L.

Search engines and social networks yield easy answers and connections, but commoditize attention. Evidence of one’s desire, curiosity, or concern is rendered down into demographics and hawked to advertisers. Disembodied and displaced, even in the most mundane computer-mediated dealings, we accommodate ourselves to synthetic environments, surveillance, bureaucratic absurdity, depersonalization and human redundancy. Captivated and distracted, interfacing with apps, algorithms and networks, minds lose consciousness of land, selves lose affective contact with others.

It’s overwhelming to think about the extensive, complicated, resource-intensive systems we depend on for our everyday wants and needs. Lately the local food and economic relocalization movements are raising consciousness about the fallibility of such systems, penetrating the denial, providing alternatives and promoting community resilience. Relocalizing communication could begin with inviting the neighbors to dinner and extend to supporting the local library.

Although everyday users may cling to their iPhones, discontent with the larger InfoTech system and its effects is simmering. For all the revolutionary ballyhoo around technology, ecological and social crises have intensified and the high speed info glut doesn’t seem to be making a dent. The idea that technology will save us is losing credibility. But if not that, what? As Lisi Krall, who is my kind of professor of economics, said recently, “Technology is our last refuge before we face what we don’t want to face.”

No technology can instill compassion or courage in a human heart. When we sideline the devices, we face Life with a capital L. And we face one another and the joys and woes of place, community, livelihood and change. For our entire experience as human beings, we’ve found instruction, awe, hazard, and sustenance in the living world. We live the future day by day, in actual places, in community with all beings. It is what we were born for, without artifice.

This article first appeared in The Journal of Wild Culture, April 1, 2015.

STEPHANIE MILLS has produced seven books, including Epicurean Simplicity, Tough Little Beauties, In Service of the Wild, and the recently released On Gandhi’s Path: Bob Swann’s Work for Peace and Community Economics. A longtime bioregionalist and veteran of the Whole Earth publications, Mills has written scores of essays and articles. Active in her community, Mills helped launch a local currency in northwest Lower Michigan, where she has lived since 1984. See Stephanie's website.

PICTURES — Pixels of sub-pixwels1, Industrial Revolution mill2, Aldo Leopold3, Broken Screen/land4.

Add new comment