"There comes a point at which the fabric of the planetary ecosystem is so shredded that the whole thing folds and we’re all dining on jellyfish." — Stephanie Mills, quoted in My North, April 18, 2011

Stephanie Mills gives one the sense that goodness is safe and sound inside the human heart. She combines the qualities of humility, honesty, and intelligence with a rare ability to feel at ease smack-dab in the muck and mire of things that don’t fit together. She also, notably, boasts an uncommon talent: she can speak and write in deadpan Chaucerian English.

I had heard of Stephanie for years: she made the headlines of both the San Francisco Chronicle and the Oakland Tribune in 1969. The commencement speech she gave at Mills College was a scandalous address entitled “The Future Is a Cruel Hoax,” called by the New York Times “perhaps the most anguished . . . of the year’s crop of valedictory speeches.” Its topic was the social/ecological instability that would result from the imminent state of overpopulation á la Anne and Paul Ehrlich and her subsequent decision to not bring children into this world. In true Mills literary form, she later called her stance “the ecofeminist version of burning a draft card.”

She radiated an aura of dignity. When she chimed in, she added her humble ironic twists that set everyone at ease . . .

After graduation, Stephanie served as editor for Earth Times’s brief four-part issuance into the emerging environmental movement, a job she sadly left because of the all-too-common lack of synchronicity between enthusiasm and bottom-line figures. In the late ‘70s she became editor of Friends of the Earth’s Not Man Apart, from which she resigned from over an internal matter.

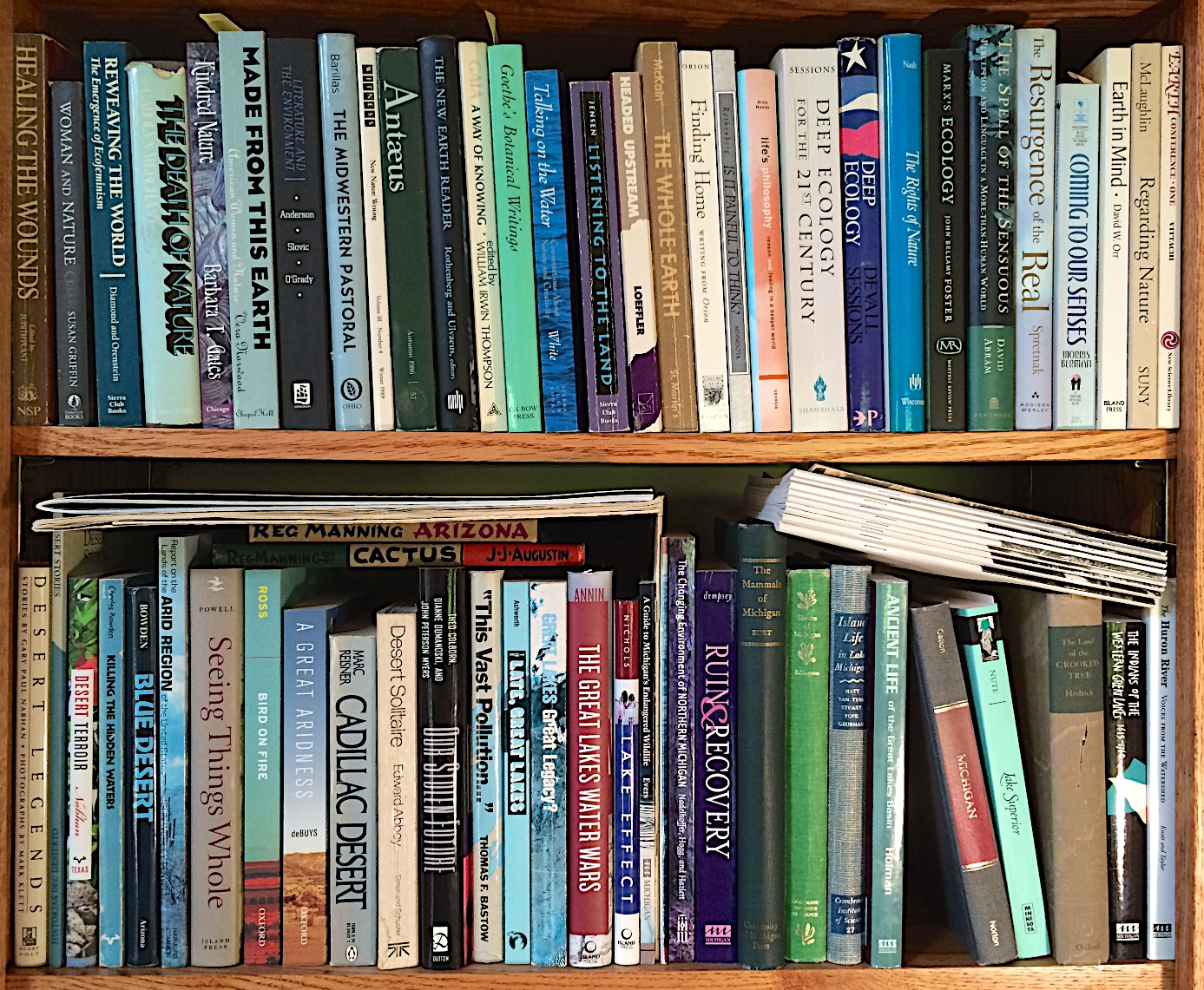

Following a couple of freelance writing gigs for conservation organizations, she went on to be assistant editor and a book reviewer for CoEvolution Quarterly and helped proofread The Next Whole Earth Catalog. While there she battled it out with editor Stewart Brand about what became his fixation on the splendors of interplanetary travel, space colonies, and the computerization of humanity. At the Quarterly she also guest-edited, with Peter Berg of the Planet Drum Foundation, an issue for the magazine on bioregionalism. It was the 1970s, the decade where moon roofs, nuclear power plants, and credit cards came into common use; yet already she was questioning technology.

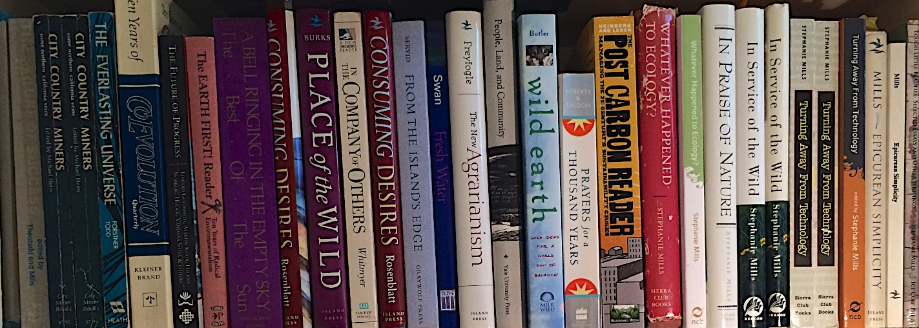

Wherever she was working, Steph always found time to write. Books to follow reflected her autodidactic, craftsmanlike leap into the field of ecology: Epicurean Simplicity on simple living, a Thoreau-inspired collection of essays called Tough Little Beauties, essays, In Service of the Wild, on ecological restoration, and On Gandhi’s Path, about radical, community-minded economist Bob Swann.

Stephanie, at ease with a found object. Lake Mead, California, 2011. Photo by Richard Register [o].

I finally met Stephanie at the 1988 Bioregional Congress in Kerrville, Texas. Sixty-some women had gathered under a circus tent apart from the men folk, and we took turns introducing ourselves. Still recovering from a divorce and a near-death car accident, both of which had demanded her innermost resources for survival, Stephanie spoke of the joys of leading a Life of the Mind. Hers was unlike any other check-in.

We reconvened at the Megatechnology and Jacques Ellul conferences initially pulled together by Jerry Mander and Helena Norberg-Hodge, starting in 1989 and running through 1996. In rooms filled with some thirty accomplished intellectuals and activists, it was often hard to get a word in edgewise. Here was Wendell Berry breaking the ice—and causing raucous hilarity—by proclaiming, “I’m a Neo-Luddite!”; Beth Burrows presenting the facts on what at that point was still the “coming ” disaster of genetic engineering; Jerry warning of the “new technologies” that would include GMOs, nanotechnology, super computers, satellites, and weapons of mass destruction that we could not yet imagine; Vandana Shiva enlightening us about the grievous socio-economic effects of “free trade” as it was foisted on India in the 1700s; John Mohawk of the Onondaga Nation reminding us of the social structures of indigenous communities that held out hope for an ecological use of technology; biologist Martha Crouch regaling us with how she left university teaching as a protest against the academy’s cooptation by bio-engineering corporations; Godfrey Reggio telling us that the problem was the system as a whole that was causing us not merely to use destructive technologies, but to live them. That first meeting took place in the ‘80s, and since then all the grievous predictions, one by one, have come true.

Through it all, Steph radiated an aura of dignity. When she chimed in, she added her humble ironic twists that set everyone at ease, and in the end she was chosen to edit the content of our discussions toward a book called Turning Away from Technology.

The question was as much a metaphor for human action as is was about the living tissue of Gaia.

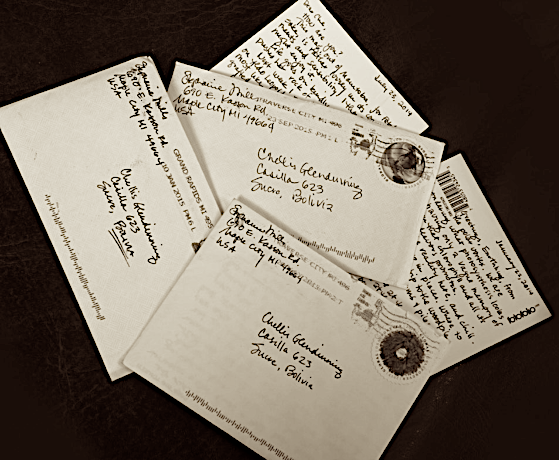

Given that we both aimed to live as off-the-grid as possible, she more rigorously than I, we began to correspond in the old-fashioned way, by hand-inked epistle. And so it was through some twenty-plus years of letters that I came to love Stephanie.

Typically, she would start each with a description of the birds visiting her plot of “woodburb” in upstate Michigan, the coolness of the lake in summer, the color of the leaves as they fluttered in the autumn wind. “It’s good to be home in the oyster-shell gray and chalk-white world,” she scratched on a postcard upon returning to Michigan after a year and a half of tending her father as he died. “Snowing, snowing, but gently. A soft pure blanket. It’s cold-teens by day. The emerald ash borer’s depredations mean that most of the firewood available is dead ash; quick to burn (if dry, which mine isn’t) and low on BTUs. Got 2 little winter survival plight shaping up here as I try to re-inhabit my post-Dad, post-Scottsdale life.”

Or this on a September day in 2014: “I’m out on my back deck for it’s a balmy sweet Fall day, with sunshine and a splendor of gold and green light streaming through the changing sugar maple leaves. It’s not too late in the year for there to be a mosquito sussing out the prospects for a meal of my blood. Crickets are trilling. Red squirrels and chipmunks are dashing about, getting their winter supplies together. A hawk is keering, a crow cawing, a blue jay is yelling. And the truck traffic goes by on the road.”

In every letter Steph’s kindness showed through. At a time when she knew that I was residing in the shadow of Job, she eloquently penned: “I picture you so dashing and full of attention and conviction and surprise, moving through excitements and past obstacles and into deeper understanding of your new milieu [in Bolivia]. . . . I hope that the moments of contrast when you contend with doubt, loneliness, and suffering, as every human must, are few and mercifully brief.”

Always attention was given to the distressing state of the planet, which she tended to capture with punchy metaphors. “It’s comforting to be with the flowers, to greet them as beloved,” she wrote. “I want to enjoy biodiversity while it still exists.” And on dramatic upheavals of weather, like hurricanes: “Instant Mumbai on the Atlantic seaboard. Could it be a perfect opportunity to stop and reconsider the whole project of modernity?”

A pile of Stephanie’s letters, 2014–15. Photo: Dorian Foto, Sucre, Bolivia.

And true to her dedication to a 'Life of the Mind', she would report on what book she was devouring, which predictably was of the ilk of Crime and Punishment, Homage to Catalonia, Paradise Lost, or War and Peace. Then, occasionally and with no small smattering of guilt, she would veer in the direction of “detective novels set in 1st-century A.C. Rome, spy novels set in Europe during WWII, and swashbuckling, intricate intrigues set in Scotland in the sixteenth century.”

This attention to the written word began early. Steph was born an only child in lushly green, palm-tree-studded Berkeley, California, and grew up in arid, saguaro-festooned Phoenix, Arizona. Her parents, Robert Mills, a mechanical engineer who sold specialty castings to the hard-rock mining industry, and Edith Mills, a homemaker, were inveterate readers and correspondents. They were also fluent speakers of both the Queen’s and colloquial English. They poured attention onto their only child, nurturing her curiosity, helping her to build a library, and engendering her independence. She attended both prep school at Windsor Hall Preparatory School and public school at North Phoenix High School.

Writing for publication began in high school. As early as 1970 she was posing the question “Whatever happened to ecology?” as a query into why the radical egalitarianism of ecology as a stencil for action had been left to men in three-piece-suits. The question was as much a metaphor for human action as is was about the living tissue of Gaia. The book she wrote in the mid-’80s, of the same name, was an integration of the Ehrlichs’ research regarding the impacts of overpopulation/development on the planet with a chronicle of her evolution as an eco-political thinker. Written with her emblematic self-effacing humor, the book features a gallop through the nascent environmental movement of the 1970s-’80s, including encounters and friendships with advertising innovator Howard Gossage, author Jerry Mander, environmentalist David Brower, save-the-whales activist Joan McIntyre, environmentalist Ponderosa Pine, bioregionalist Peter Berg, feminist Starhawk, and a host of other activists of note — just as it explores political conundrums such as the practice of abortion, anthropocentrism, and Inside-the-Beltway reform versus Never-Say-Die radical action versus Walk-the-Talk/Do-It-Yourself sustainable withdrawal from the system. Always it reveals Steph’s irrepressible inclination to say and write what she sees and wishes others would see — no matter the repercussions for future employability.

A small portion of Stephanie’s immense library (for more of it, go here.) Photo by Whitney Smith.

One of the last times Steph and I clinked cups of Lapsang Souchong was at the 1995 Learning Alliance conference “Technology and Its Discontents” in New York City. Along with Kirkpatrick Sale, Steph and I were on the verge of performing our Interview with a Luddite play and feeling rather giddy. Who knew that it was all to end? Who understood that the global economy’s preference for the privatization of the world’s riches would soon suck dry the monies available to our heresies? Or could predict that our most loyal funder, Doug Tompkins, would decide that a more direct use of his capital to save the planet’s ecology would be to buy up wild lands in Patagonia? We still believed that the luxury of yearly get-togethers to discuss pressing issues involving technology, the planet, and social movements would go on as it always had.

In her letters Steph sometimes refers to the sense she has of being a pariah at dinner parties: she feels compelled to challenge people’s belief in the future by regaling them with the state of a planet on the edge of collapse. The compulsion lets loose its Gorgonian locks due to the fact that she keeps up with the details: the daily animal extinctions, unbridled deforestation and desertification, the ever-widening breakdown of entire ecosystems. Not to mention the held-together-by-toothpicks financial markets, the ongoing wars, nuclear buildup, and social breakdown, the grim prospects of Peak Oil, and the equally grim impacts of barraging living beings with electromagnetic radiation. I am reminded of a Sylvia cartoon by feminist Nicole Hollander in which our wry and cynical protagonist is sitting at the neighborhood bar regaling her cohort about the perils of nuclear war when the other retorts: “Sylvia, don’t make yourself unpopular.”

Perhaps by way of karmic justice, Steph was invited to be a fellow of the Post Carbon Institute. Early on in this endeavor she traveled to California to chow down a weekend’s worth of dinners with Peak Oil expert Richard Heinberg, sustainability activist Gloria Flora, botanist Wes Jackson, photographer Zenobia Barlow, and other systems thinkers, analysts, and policy makers whose knowledge and distress equaled her own. The 2010 retreat was held at the Brower Center in Berkeley for the purpose of clarifying the institute’s mission, strategizing about communicating to the public, and sharing Steph’s over-the-edge vision of the precipice that humanity currently straddles; in the presence of such like-minded peers, Steph was able to feel sane again.

Back in Michigan, she has become involved in the effort to de-globalize/ re-localize by creating a money system generated via direct trade and earned hours of service. “Who knows what’s going to become of the U.S. economy,” she told an interviewer in 2011. “It’s too large a system to manage intelligently and for the common good, whereas at the local level the feedback loops are shorter.” The work involves initiating a home-grown currency, called Bay Bucks, in the Grand Traverse bioregion as a way to encourage local relationships, sustainability, and investment. “If we got a deflationary depression and cash got scarce, there would still be people with skills, people producing goods . . . and that’s why there were hundreds of local currencies in the U.S. during the Depression.”

In regards to her preoccupation with the environment, Steph wrote in one letter that the next mission was not just the task of reintroducing ourselves into the natural world; it was to face the reality of nature’s galloping demise and to create honorable ways to live in/with this unspeakable tragedy. Like everyone else who has attempted the challenge, Steph hasn’t mastered an entirely adequate response. One would have to inquire then: whatever happened to ecology?

She certainly has never stopped asking. ō

"If a technology is elegant, biodegradable, made from renewable materials and employs a minimum of

muscular, water or wind energy, is responsive, beautiful in its way, and challenging to the user in that it

develops the user's senses and strength — it may comport with nature.." — S.M. from Counterpunch >

CHELLIS GLENDINNING is JWC´s Editor-on-the-Lam and the author of nine books on the societal/psychological axis embedded in social issues. Off the Map and Chiva both won National Federation of Press Women (US) book award in non-fiction. Her latest are Ojectos, a novel in Spanish published by Editorial 3600 in Bolivia, and In the Company of Rebels: A Generational Memoir of Bohemians, Deep Heads, and History Makers (New Village Press, 2019), from which this article is taken. She lives in Chuquisaca, Bolivia. View Chellis' site.

Comments

Wonderful to see Chellis…

Wonderful to see Chellis Glendinning’s work again. I participated in her full page New York Times piece on inhabited wilderness and have long been an admirer of her work when she lived in New Mexico. And she’s writing this time about another of my bioregionalist heroes, Stephanie Mills, whose work has been an inspiration all my life — from my San Francisco days tracking the Whole Earth Catalogue and participating with Planet Drum to being Earth First poetry editor and Green Party county commissioner in Colorado. Wonderful to learn of the deep connection between these two amazing women.

Add new comment