Stone Ewe Pre-Face

this piece, this

part, this

per haps

story, this

probably may

be more

poem playing

at

being

a fiction has an

embedded

chain’s

bit (not

steel between

a beast’s

teeth) yet

something to

clink, some

thing some

clues do

some poss

able

weather where

swift air

terrifies with

whinnies

and is

laden

with huge

rain

a clue too:

Dwo

(pronounced to

rhyme with too)

over edge

split-bed clear

find secret weeds

they seem

dropped threads’

anywhere-freedom

picking

me it

queerly first

what go trees me?

every

thing

centre

roots

water looking

The Ewe Stone

nothing-&-stone mingle wind

— Holly North

The middle-aged man stared at the rock just in front of his face. The toe-tips of his mountain boots were snug on a thin lip of stone. As he balanced, and gazed at what he was balancing on, the stone’s rugosities stayed utterly still, as they had done for hundreds of millions of years.

Yet the man found himself making these solid ripples change shape; he saw a continent’s outline, and a goat’s head, and then the hungry grimace of some strange un-known beast . . . which then caused him to recall the little church towards the valley’s mouth, five miles away and two-thousand feet or so below. Beside the church yard’s single yew tree there was a roughly hewn Celtic cross, and below the cross a small face-shape with a hole in it, no doubt meant to be a mouth. He did not lose contact with the hard ancient substance he was climbing on, but so very briefly one of his carefully placed feet slid ever-so slightly along the stone lip. He rebuked himself for letting his mind go astray. He was not used to losing his concentration. He needed to stay focused. The climbing was not desperately hard, but the rock was becoming greasy.

It was twelve years ago that he was last here. He had thought the climb would be a pleasant remembering. But a niggling doubt had crept down the back of his neck. He was also a man not used to doubt.

He had uncommon stamina, and an appetite for, as he often called it: Simply ballsing it out.

The ragged ridge of the fell across the valley had grown a grey fur of cloud. He watched it swell to a wavering gauze of moist air that started to creep down the craggy slopes opposite. He was alone, and un-roped. Perhaps he should’ve waited a day or two more, waited for more settled weather.

Holly would’ve waited. She was a bold climber, and nothing much worried her, but she was also patient, and would always think carefully ahead. Where as he would rely on his few gifts: physical precision and agility on all kinds of ground be it clean rough stone or algae-stained slabs or friable walls or decrepit ice. And he had uncommon stamina, and an appetite for, as he often called it: Simply ballsing it out.

A few straightforward moves brought him to a small ledge. The toe of his right boot nestled under a few fronds of heather. The heather held a constellation of bright droplets that jiggled as he moved his foot. Again, he rebuked himself. The little jewels were a distraction, and not what he was used to paying his attention to. He turned to look down the valley. The white thread of the beck wriggled. And the grey gauze on the fellside opposite had fattened further into a tumbling mass of hairy mist – it quickly engulfed each outcrop it fell past. In all his years of being amongst mountains he had never seen hill-fog move with such sullen weight.

He felt stupid and annoyed with himself. It was just weather, and weather was the medium through which the mountaineer moved . . . that was all it was. He was imagining things.

He looked straight down at the little ragged-edged tarn at the base of the crag. It shimmered gently as slanting sunlight skidded its surface. The path beside the tarn, that led back down towards the beck – the neat inevitability of its threading its way around knolls and craglets was as comforting as a familiar story. He heard a faint cuck-ooo cuck-ooo rise up from somewhere far down the valley. Briefly he thought he caught on the slight breeze a whiff of fresh mown grass. They were cutting for silage in the bigger fields, just before the bridge over the beck where the lane crossed and went on up to the church.

He looked up the crag. He clearly remembered the tricky section just ahead, which led to the arête overlooking the dark cleft of the North Gully. The pitch followed a shallow groove full of vertical curving ripples like water on a wind-blown tarn. The ripples looked deceptively positive, but when you reached them they turned out to be smooth as adders.

That’s the way she put it. And he remembered her wry smile, and the direct sweet lance of her gaze as she said it. He hadn’t thought of that moment in years, but here it was. He smiled to himself. His anger and the strange niggling that had crept down his spine since setting foot and fingers on this crag, it subsided a little. She was always so good at calming him down.

He had climbed the ‘groove of adders’ a number of times, and once he’d even done it whilst pound-coin-sized snowflakes ticked on his hood and blurred the rock. Today the ripples were cool and greasy, nothing he was not used to. A dry crock-crock suddenly cracked gently in his ear, and through his eye-corner he caught the black flickering flag of a raven slide down the sky past him. The bird’s agility and brilliance inspired him. He set to.

The man leant away from one of the sharper ripples, the finger-skin of both hands pressed hard, pulling against the rock. He carefully plugged the front rim of his left boot into one of the hip-like curves of the thickest ripple. His right foot had nothing much to stand on. This was the move, at least of this pitch. In front of his nose now, a stringy black beetle crawled across one ripple and then up and down another. It scurried so swiftly that he thought he saw a tiny dark horse galloping over silver hills. For an instant the beetle’s back had glinted. He felt the left boot begin to fade. The grip – the contact – that usually felt like a tight wire running from his toe up his leg and into his stomach, where he would feel it and pull it neatly with his gut muscles . . . suddenly the tension dissolved. The grip’s crispness melted. The beetle had disappeared. He let out a growl and cursed himself. His foot was slipping. And he was frightened. He could feel his planet’s mass pulling at him. He had not felt fear like this ever before.

He was falling . . . and then he was somehow on the rock again and his limbs making blurred movements and his fingertips feeling out a quick repetition of tapping and scrapes his breathing thick liquidy bag-fulls of gasps eyes wide open but what he saw was just stone-coloured shapes wavering all that was happening and all he did was governed by touch.

He had reached the easy angled arête overlooking the North Gully. He stood trembling on big holds. He could hardly recall the last few moments, he simply could not account for how he was now still alive. His years of experience and consolidated skill must’ve suddenly kicked in, he must’ve switched to some kind of ‘automatic’. He was partly amazed at what his body had just done, yet he had never climbed so badly. He yelled, You fuckwit! Wit! echoed back at him, out from the deep gully to his immediate right.

He turned to look down the valley; he could see nothing of it, he was now surrounded by a moist grey swirling slightly-luminescent floss. The heather on the ridge opposite, across the gully, was bathed in a shiny grey fluid, and was as still as if it had been carefully carved out of metal into astounding intricacy. Yes, the heather and the grasses were absolutely still, he was sure of it; yet he could feel a strong breeze rushing up past his ears, he could hear the straps on his rucksack gently clattering. He felt a lone raindrop splat on his scalp. Then there was another. Then. Another. He could feel cold water wriggling amongst his hairs. Now one drop rolled what he imagined as a silvery pulsating trail down his nape under his fleece and into the warm middle of his back. And then he found himself seeing – or was it somehow feeling? – raindrops falling upwards blown off his skull in the updraft. He shook his head and scrunched his eyes. And he swore again and his voice again bounced back at him out of the gully. He needed to pull himself together. What the hell was wrong with him?

Think of Holly. He brought her face into focus her green eyes kind yet dangerously sharp the glint in each of those eyes clear as a star-point shot across space like a lighthouse pulse on an horizon a sign of safety and yet also of danger. He suddenly realised that’s what it was – that exquisite mixture of uncertainty, and yet trust. He smiled to himself again. He listened to her voice. She was banging on again about poetry . . . but he was listening now. She was talking about Coleridge, describing excitedly yet precisely as if she had been there with the poet, how he lay down and writhed on Scafell’s rocky ground as thunder raged round him and lightening . . . it never actually struck his body, but it electrocuted something deep down in the dark of him, made a crisp shadow of something never seen before suddenly loom on the inside of his dazzling skull. She talked about climbers today, and how easy it is when you know so many have done these things before you, or at least things similar if not quite as hard. But Coleridge, no one had ever done anything like he did. That descent of Broad Stand . . . he could hear her clearly and he listened to her properly for the first time as she described that descent hold by hold she detailed the feel of each shape made by the ancient rock as that foolish yet somehow wise poet touched the mountain’s stone.

And then he remembered where he was now standing: on slick rock in pouring rain on an arête some three hundred feet above the little tarn mouthing its silent grey gasp lost in the mist below. And he was nothing like focused, his brain was carrying on in all directions. A wave of anger rolled through him and then broke ferociously. He screamed into the gully. No words. Just thick tangled wire strands of sound fell out of his mouth and then jabbed back at him bounced off the gully’s walls.

He needed to get moving, and needed to move well. He had sixty or so feet ahead of him before the broad ledge, and after that just scrambling up the ridge. But, the last twelve-foot of climbing before the sanctuary of the ledge was harder than ‘the adders’ . . . and in this rain and in big boots . . . He wished he’d brought rockshoes, but then rockshoes would be useless now. His mind roamed around for ideas. He had no oversized woollen socks with him, that he could pull over the mountain boots, the fibres of which would help him grip the soaked slippery stone.

He tried to focus, and calm his anger . . . but again an ocean roller of rage crashed over him. He was stupid, for blundering into this trap, this rock-trap, no, this middle-aged, no, senile mind-trap. Again he threw his insult into the gully – Fuckwit! – and waited a fraction of a second before again half the word rebounded on him. Wit!

He now wanted nothing more than to get away as quickly as possibel. He tensed himself. Pulled the buzzing wires of his heart tight and connected the wires of his muscles to the beating centre of him. He looked straight up the crag, at the rock to come. But as he craned his neck upwards something seemed to flare in the corner of his right eye. His senses were acute, his feelings wriggled to points. He was about to move upwards. But. He stopped.

Over to his right, across the gully . . . earlier on he thought he’d seen a perched boulder on the ridge, a boulder he’d never noticed before, but thought nothing of it . . . he could see now that it wasn’t a boulder at all – it was a dark grey sheep, probably a ewe, but oddly he wasn’t sure. Of course it was a ewe, a tup wouldn’t be up here high on the fell. Whatever, it was standing stock still. On thick hoar-frosted legs. And it was staring at him. He found himself staring back at it. The black grooves in its eyeballs pulsated a thick unintelligible but somehow knowing message. He pulled his eyes away from its gaze, and carefully observed the beast. Yes, the horns were polled, so a yowe it was, but a large one. In fact she was as big as any tup, Herdwick or otherwise, he’d ever seen. Actually, she seemed bigger than any tup he’d seen. She was huge. And she was statue-still, yet her gaze propelled a fluid energy. Her rugged bluey grey wool held droplets of rain. She was certainly living: wisps of steam rose from her underneath to writhe delicately in the woollen canyons of her fleece. Then suddenly she shook, a rolling neck-to-rump-wave like a dog’s shake, flinging droplets off of her. And then she was utterly still again. Staring.

As a boy he’d worked at least four of his summers on his uncle’s remote farm, right up towards the head of Detterdale, over on the Western edge of The District. He knew exactly what Herdwicks looked like, and he knew something of their moods, and knew their postures, and most of their ways of going about the fells. Over the years, and in all seasons wandering the fells, he’d gained an affection for the beasts. Their sturdy woollen legs, and sure-footedness. Their wide, somehow kind and almost religiously resigned faces. And their simply sticking it out and going on with things, busily methodically cropping the wiry fell grasses with wind ruffling their fleeces or even snow gathering on their backs. Funny, he’d never thought these things so clearly before. Holly would’ve made a sarcastic but sweet comment about these thoughts. She would’ve approved.

But the beast now gazing at him, this creature had none of that Herdwick kindness. It was the same breed for sure, but this one, she was so big. And her stare . . . her stare seemed malevolent. He was being bloody stupid again. If this was the Rockies and that was a mountain goat, well perhaps he had something to be wary of. But no, this was just a sheep. And besides, there was a broad gully between him and it.

He started laughing, his cackle resonating in the gully, and he began to recall how a goat in Corsica had indeed bucked him and knocked him off the mountain path he was on. How he had laughed as the goat came at him its dangling ears flapping the surprise comedy of it all the thud of its skull against his thigh and how Holly and Jerry had laughed too and even as he was rolling down the scree he couldn’t help spewing out big gulps of clattering laughter laughter at the joyful daftness of having been flicked off a mountain by a brown nanny goat. He was a very young man then, and despite tumbling some two hundred feet down steep scree he hardly hurt himself at all. After scrabbling back up to the others he proudly showed them his only wound – red jewels dripping off the point of his elbow, glittering in the cool blue air.

This wasn’t funny though. Again he realised his mind had just taken leave of his body, and had started wandering all over the shop. And again he wanted to curse and yell, but this time remembered his voice rebounding back at him from the gully. He kept silent. All the noise he’d so far made had made no difference to the beast. The stony ewe absolutely still was still there. She stared at him. Yes, he was certain, she was actually staring at him. And she seemed to know it.

He needed to move, and he needed to move so very very well. He could feel the ewe’s eyes on him. He glared upwards at what was to come. And strangely that animal gaze from across the way – he held it somewhere in the back of his head and somehow he connected it to the wiry pulsating mass of his heart and the wires of precision tightened in him and he was there now suddenly there at the crux the horribly slippery rock and small wrong-way-pointing holds all in his power and he could see his fingers crisply in focus and feel the delicate pattern of friction under the weather’s grease and he watched himself it seemed six or so feet away from and behind himself and he climbed the soaking pitch better than he’d climbed any pitch ever before.

He stood on the big ledge. It was more of a deep bay, a balcony of expansive safety. The gully was no longer in view, the bay’s tall right wall obscured it. The surrounding walls offered some shelter from the weather, but every now and again a buffet of wind spiralled in and then spiralled out. And the rain was no longer falling straight down, instead the wind had set it aslant, or if not aslant it momentarily spattered as gusts swirled it. And the rain was becoming sticky with floppy grey crystals. His hands were raw with cold. When he’d started this climb it was spring, and yet it was now November. He stood still, statue-still he thought. He stood on the vast ledge astounded to be there.

Whatever the bloody ewe wanted with him, somehow he’d got the better of it, used his indignation at the absurdity of her. That was it, that was what he’d done. He wasn’t even sure if there had even been a ewe. No. There hadn’t, of course that was it, yes! – he’d made the whole damn thing up to get him out of his fix. He’d read of such motivating hallucinations in tales of mountaineering daring-do. He smirked. He felt silly. Sheepish indeed. He heard himself laugh his forced guffaw streaming out a fraying stringy trail as the wind picked it up and took it away.

He looked beyond the big ledge up the remaining ridge. The scrambling was blocky, spiky and festooned with holds. But the soppy crystals now being squeezed out of the woollen sky were blunting the spikes and filling the holds and smearing the rock. The wind speed was picking up. The scramble was not going to be a doddle. But it’d go. It would, of course, have to.

The old eyes in the young man’s face kept locked on the other man’s. Then turned away.

His legs felt as if the gathering sleet-sludge was already up to his thighs. He looked down, it was only a centimetre thick, if that. A thin layer was gathering on the tops of his boots. But his legs felt stuck, as if his own muscles were huge slugs clamped to his bones, frozen to his bones. He was knackered, more knackered than he’d ever been. More goosed than when he’d topped out on McKinley after days of vertical, brutal mixed ground, and in howling wind. How could that be?

Denali, it’s called Denali not bloody McKinley! He heard her voice mix momentarily into swift wet air. She had quite a deep voice but with a bright edge. A slight sing that dissolved in amongst the throaty yet mellow notes of her turns of phrase. And she sometimes had such odd but just-so ways of saying things. He should’ve said as much to her. Her voice fell back in amongst the background hiss of wind and dwindled and then was gone.

He felt bewildered – a cold hollow growing in his gut. He recalled the image of the ewe. Stone-still still staring. Then a slicing pang of fright as if an icicle had been pushed under his ribcage. The cold-razor ache fanned out up his chest and settled in his throat. He gulped cold. Leaning against the ledge’s largest rhyolite block there was a figure. Stupidly he had expected the ewe to appear from the small cave at the back of the bay . . . and in the instant he dismissed this ridiculous fear the large block that dominated the ledge seemed to grow a tall shape out of its flank. There was a man leaning against the stone. There actually was a man.

Keeping his eyes on the figure, he knelt. Then he bowed his head and fixed his gaze to the ground. He pressed a palm into the rock’s cold undulations, then lifted the hand and thwacked it down again to test his world’s solidness. His hand buzzed with the impact, but it felt real and that was good. He squeezed his eyes shut. He looked like a man in the starting blocks, or some big cat about to look up and then pounce. When he opened his eyes the bay would be empty. The side of the big block would be empty – the block would only be gathering the air’s wet snow.

He opened his eyes. Wide. Immediately his body pulled into its lungs a thick soaked rope of air. His gasp’s hiss outstripped that of the wind. The man had not gone. The figure was still there.

This other man, leaning against the block, suddenly stood upright. He was wearing a grey suit, a thin black tie against a white shirt. He had on brown brogues. Of course the suit was ruined, completely soaked. All down the left arm there was a dark green smear of algae. And the outside seam of the trousers’ left leg had split to the knee. The wet rag flapped each time a gust curled round the bay. But the figure didn’t seem much bothered by the state of his clothes. Claggy snow gathered on the man’s broad shoulders and flecked his wavy black hair. He was a young man, but with a direct steady gaze that seemed to pass across an ancient distance. The dark eyes were set deep below thick eyebrows. The nose was prominent and slightly hooked, giving the young pale face a hawkish precision. The lips were thin but distinct and strong. And the young man’s jaw was large and square.

Then this younger, yet somehow decades older man spoke: In a huge, open-wide, leaping eye of a bear A mountain gleams in the pupil. His accent had been formed in Yorkshire. The voice was at once gritty and yet smooth like river moving. I see the dark pool In the snow On that huge hill But I cannot see If its water’s full Of foetus or food. There was a slight tremble as the syllables bled precisely from between the thin lips. But the tremble in the voice, although making the middle-aged man think of fear, was not at all a tremble of weakness, it was more the kind of wavering resonance made by a massive bronze bell. That meaningless cry with its sea-voice Churning equally its dead-&-alive. And yet at the same time there was a distinct glimmer of gentleness in the voice, and a reassuring certainty, as if each word had been given like a pebble, pressed into the palm, unpolished by cloths, but already gleaming. Perhaps the words were polished only by the wind. Your climbing Your climbing Slides my skeleton slowly through space.

Now the young man smiled. It was not too dissimilar to one of Holly’s more mysterious smiles, the one that would make him feel judged sharply and yet at the same time collude with him.

That’s a good thought! The young man said to him. Yes, she colludes with you. All those words of hers lace the air. Even now she tightens your ears to feel. Here is her gesture Here is her fern Hear her unfurl. The steady yet wavering yet stony yet watery voice let loose its sounds to be caught by the sleet-speckled air to be torn away and torn up and mixed in and lost amongst uncountable atoms of elements:

Meaningless living appearance:

Night’s self-pebble.

Universe sleep — sun’s foetus.

The wind with nothing.

The stone’s directions.

Sea to fallen conditions;

Her aeon develops.

Variant angels bow.

The old eyes in the young man’s face kept locked on the other man’s. Then turned away. And swiftly as a deer startled or hawk stooping the tall drenched grey-suited figure leapt away from the large block and was then on the bay’s tall dark-green-greasy right wall making crisp person-shapes and gestures of clinging and balancing and pushing and connecting these gestures into one single fluid alphabet of motion up the impossibly hard wall. Then the figure was gone.

This was too much. He simply was not going to accept this. He smacked his forehead repeatedly, whispering: Stupid! Stupid! Stupid! He could hardly tell if the whispers came from his throat or if they were wind curling in his ears.

Quickly he got stuck into the final scramble leading up the ridge. He made no decisions. His body simply carried its small heat glimmering within him over the slippery blocks as the grey rumbling syrupy wind wrapped its sleet-tendrils round his frame and tried to pull or push him off the mountain. But the wind could not.

The sleet had now fluffed to snow. The climb was behind him. He staggered through feathery roiling flakes. The light was odd — bright then shadowy sweeping swathes as gaps in higher-up clouds opened and closed. He knew the ground ahead: a little plateau of craglets and knolls. But the wavering snow-strands and sudden twisters of speckled air put contorted veils and masks in front of familiar shapes. The slanting light was fading; it was much later than he’d planned.

And then on the close horizon, on a knoll, pixelated by the laden air, there it was again. No! No, that could be any ewe. It wasn’t the same. It disappeared for an instant into the weather, than came back crisp as sudden sunlight edged it. He squinted back at it, its shape fading in and out of this granular world he had suddenly found himself in. But even at this distance, some hundred metres, and through the hiss-interference, he could see, or perhaps feel, the eyeballs’ deep black stripes pinned on him. It was the same ewe.

He pushed ahead in amongst the knolly ground. He was looking for the narrow tarn. Once he found that he could be certain of his position. The reed tussocks and rough grass were bristling with clinging flakes. Whenever he hit boggy ground each squelched step seeped back black wet through the settling snow. As he moved amongst the undulations he glimpsed twice more the shape of the ewe. She was following.

This was the place: he rounded the little pyramid crag dappled with deep pockets. He stood at the entrance to a small corridor of flat ground nestled amongst the plateau’s craggy hummocks. And lying spirit-level-flat and black the length of this geological lane was the narrow tarn. From where he stood the corridor ran south to north, and was well sheltered from the cold easterly. He stepped in. The place was hushed and felt almost indoors compared to the surrounding windswept land. The black water rippled gently as white falling flecks vanished through its membrane. Here and there the tarn was frilled with spiky reeds, all gathering falling crystals. And intermittently as the strange light pulsated its swathes of gleam and shade the tarn’s skin would buzz swarms of glisten and then suddenly snap back silent and blacken so the falling specks again were seen clearly passing from air into abyss. Carefully he moved along the tarn’s edge. Then stopped.

At the other end of the corridor, ahead of him, she was there again. He simply turned his back on her.

He stood absolutely still, statue-still he decided. And he ignored the absurdity. He listened to the sough of flakes and the glossy glugging at the tarn’s edge, and beyond that the wind rubbing along rocks and snowy grass. And then he could hear a sudden acceleration of hooves. He tried to think of other things, but he found the sound of a horse cantering into gallop. And then a bear’s steaming sawing roar and grimace loomed through his mind, his entrails hot with terror. And now a wolf’s howl. And wolves’ snouts jabbing at him, and rows of slick glinting teeth gripping his flesh. The rumbling hooves were gaining. He could no longer ignore it. He spun round and instantly the ewe’s head with a flick hard and precise as a goat’s thumped into the side of his left knee and dragged up his thigh and took his feet from under him he was wheeling round sideways an iciness suddenly clamping round him up to his waist. And then she was gone.

Fuuuck! fuuck! fuck! He dragged himself out of the tarn, and tried to stand, and tried to rub and squeeze away the water from his trousers. He didn’t think anything was broken, but his right knee — suddenly the ligaments were vibrating horribly and a deep dull ache bloomed through bone.

And then the middle-aged man began laughing. There he was alone in the snowy wind soaking wet by a black tarn a sheep had just flicked him into. He bent over with his right hand on his good knee, and he laughed huge gulps. And then just as quickly as his laughing had begun, it left him, as if the wind had instantly sucked out of him the rippling rhythm of his laughter and he was left spent.

He flopped down to sit in the snowy grass, then immediately stood up again and made the effort to take off his rucksack, and then sat back down on that. He sat for minutes with his jaw cupped by his right hand and his elbow propped on his good knee, and he stared at the black water wobbling gently just a few feet in front of him. He felt the wet cold round his legs and loins cling. Then the ache in his knee was like some kind of burning light, but when he looked down at it there was no light at all, just his outstretched leg with snow settling on it. He stared into the black water hardly noticing his juddering muscles protesting the cold. He stared. And a pressure within him and from without was immense and pinned him to the moment. If he closed his eyes now he would sleep. He blinked. Then rubbed his eyes with his wet knuckles.

He had a fair way to go to get down to the valley, and then back to his car parked by the church. Even in decent weather there was a good two hours in it, at least without running. But with his knee and being soaked in this wind, and what with the increasing snow and the decreasing light . . . and this feeling so utterly spent and not knowing why . . . he knew he was actually in trouble. Here in the little hills not many miles from his childhood home . . . how odd that after all it was these little hills that would take him.

Instantly he heard Holly rebuke him. He turned round to see behind him. Of course, no one was there. But yes, what the hell was he thinking? He could never have imagined that he of all people could’ve simply sat down and given up on his life. We need a plan Batman! And he saw her smile again. But even though he wanted so much to reach into the falling crystals and the limitless air and embrace her and tumble away across some incomprehensible ancient distance . . . he resisted. She smiled at him, warmly.

And so he was now back on task, and soon he’d be bang on target, he had to be, he had to get packing, and he had to get up, and had to just go. For a moment he cast around for a cunning plan, and then he remembered. Yes, Holly and he had once winter-climbed the North Gully.

They had set off in foul weather, and when they topped out it was full blizzard. They had huddled together next to the narrow tarn, which was thick-lidded with ice, snowflakes swishing over it. And he had started to wonder how the hell they were going to get back; the wind was so ferocious, and the sharp speeding crystals vicious. He’d suggested crawling back to the gully, but they had climbed ropeless, and down-climbing amongst growing spindrift didn’t look good. No problemo! she said, for she had spotted on the map, weeks before, a small remote building in the next valley along, not too far away from the narrow tarn. On the map, next to the building’s square black outline the cartographer had drawn a single tiny pale green pine. She’d then visited this little stone building and found it hunkered amongst five Scots pines. And its roof was good and it was full of hay. She had led the way to this shelter, both of them often forced to crawl through the snow under the wind’s rumbling lid. When they opened the little barn’s door, and then shut it tight again behind them, they stepped instantly from pitiless storm into a peaceful den filled with the sweet smell of dried grass.

He needed to forget the ewe. He had to put everything into pushing on towards the barn. He needed to find the faint path that led eastwards out of the knolls to open fellside. It was four hundred-ish metres further north from the north end of the tarn. Then after following the path for half a K or so, he’d have to leave it to find the top of the scree gully that would take him quickly down the north facing fellside into the barn’s lonely valley. There were a few little cairns along the path, and there was a distinct elbow as the path crossed a crease in the hillside. It was at the elbow that he should leave for the scree gully. In his mind the images of the ground ahead were distinct, as were the images of the map of the area that he’d studied often, but long ago . . . and he would’ve said that once he knew the ground fairly well, but still he couldn’t account for such detailed clarity of recollection.

By now the sun had set, and the greyness of the air began to tinge with thickening purple. The tarn was behind him, he limped northwards following his compass. His eyes strained at the grey-white ground with each step. He was waiting for the path; he had to be ready to pick out the thread of it amongst the thickening flakes scurrying through the grasses.

And then he was there — the small cone of a cairn suddenly resolved in front of him. He was blessing whatever luck had found him and put him by the cairn when the ewe that he’d tried so hard to forget was suddenly again standing. In front of him. Still. As when he’d first seen her on the ridge across the North Gully. Earlier in the day. A day. That already as he was. Finishing it seemed. From long. Long ago. She was just twenty feet away from him. Still. Staring.

He really did think he’d imagined her. Despite his buckling knee and the pain, and the memory of the bone of the ewe’s head connecting with the bones of his leg, he really did think he’d imagined her. Anger rose in him as if a collie had nipped the top of his calf. The ewe just stood still. Staring. Be off with you you fucker! He waggled his arms at her furiously, and wailed like a wolf. She stood. Then in a single ratchety motion he staggered and stooped and scooped up a stone from the cairn and as he stood straight again pushing up most of his weight with his good leg he swung his arm and let loose the stone towards his target. The precision of his shot shocked him. The stone made a sharp hollow clat as it impacted with her snout. Instantly blood bloomed from her nostril. She bowed her head and pawed at the pain with her hoof. Black drops spotted amongst grass tips poking through snow. And some black strands dangled down the wind. Then the ewe lifted her eyes to him once more before she bleated her stony baah and then turned from him and bounded away her woollen rump bouncing back up towards the knolls in the direction of the narrow tarn her grey shrinking shape quickly brushed away by the streaming wall of scratchy flakes.

He stood and stared after her. Stared into the grey swish of speckled veils backed by purpling shadows. He could see nothing more of her. And he suddenly felt sorrow and was ashamed. He thought of his uncle’s ewes. And guilt suddenly crawled into him. She was, of course, just a sheep.

The stippled wind’s sting pressed against his face. He followed along the stringy path, and found the elbow in it. And then soon after that in darkness his headtorch jiggling its beam through flecks he speedily skidded and rode down the snow-muffled clatter of the scree descending an ancient escalator away from the higher ground holding the black narrow level of the tarn so hung above him as much in his mind as it was on the actual frame of the Earth the secrecy of that snowflake-coated scree slipping him sliding him down down into the valley’s fold his knee jolting electrically.

Now he limped along the valley path towards the little barn and its five Scots pines. The snow was thickening quickly and squeaked beneath his steps. And the track he left in the grey-whiteness of this yielding substance was a repetition of one clean boot-print and one print scuffed and this soft substance into which he divulged his injured trail was not yet hours old and after this night and another day would be melted gone. And the beck beside the path followed him and his deep tiredness effortlessly with its careless noise. He thought he could hear a voice in the water or was it remembering something she’d read to him? This is where all The stars wear through This is where all The angels wear thread Bare their gowns of sky. He wanted so much to be at the shelter now, he longed for the pines and the barn to grow out of darkness.

Then he was there pushing against the wood of the door his fingers fumbling the latch the door creaked as it opened. Then. Creaked as it was shut. Again. Immediately the snug quietness of the little place enveloped him. The dark white-flecked wind so far away and faint hissed peacefully through the pines outside. He slumped on to hay bales and let himself flop backwards. His headtorch picked out the cobwebbed beams and the backs of the thick slates keeping the sky away from him. He quickly slipped into an exhausted stupor, his mind emptying like a pool suddenly undammed. It was as if a part of his brain had fallen away from him. The ewe and all of that day already were gone far from him. He sank to sleep.

But then after a while of sleep’s thick breathing the sweet scent of the hay pulled through his nose entered his memories and lit them. He sat up suddenly and thought of lush grass growing then cut and dried in sun. And then his shoulders trembled and a great shaking took hold of him and bursting sobs came out from his mouth as his eyes brimmed and his cheeks streamed and his nose dripped. A long shuddering wail flowed out from his throat. He knew he was weeping in a way he’d only ever witnessed once before. And that he’d forgotten long ago. He wept as once his mother had. As his small child-self sat on the trembling bed close to her stroking her huge warm hands. ≈©

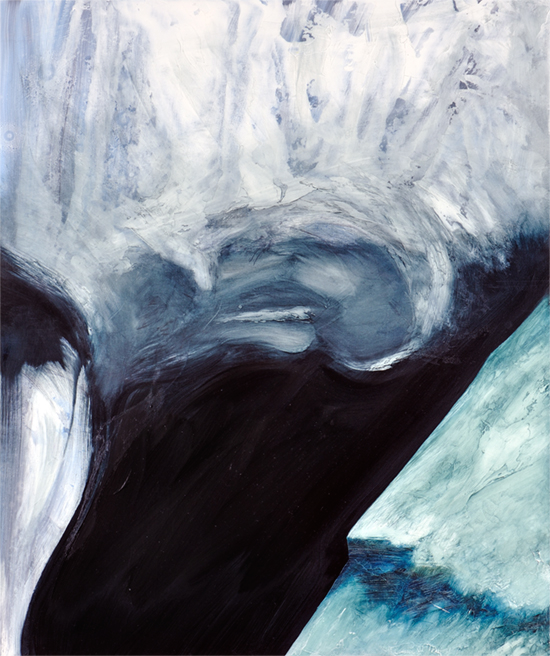

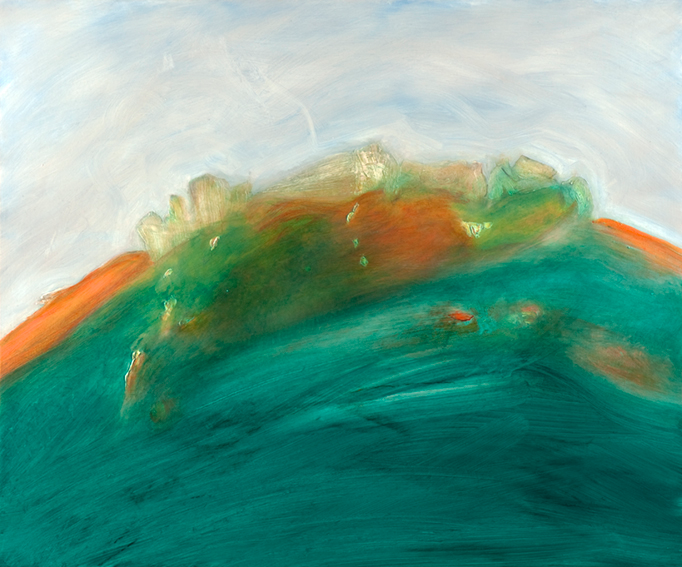

About the Paintings

The paintings of Paul Evans featured in this article have been 'borrowed' (and re-imagined) from The Seven Wonders | De Mirabilibus Pecci (https://seven-wonders.org/about/) project: an ongoing collaboration between the artist Paul Evans, poets James Caruth, Matthew Clegg, Angelina D’Roza, Mark Goodwin, Rob Hindle, Chris Jones, Helen Mort, Fay Musselwhite, Alistair Noon and Peter Riley. The project has been curated by Brian Lewis, publisher of Longbarrow Press.

Paintings from this project have been selected for ‘The Ewe Stone' by the editors of The Journal of Wild Culture. The intention is not to ‘illustrate’ the article but to colour it, texture it, and present some visual 'ground’ that will connect with and project 'something' of the invented 'District' in the story. By presenting the paintings here sans titre, they assume something of the character of a mythological world that is a 'none place'.

The two completed stages of the Seven Wonders (https://seven-wonders.org/about/) took place during 2010 and 2015. Both phases have featured in exhibitions at Cupola Contemporary Art, Sheffield, UK.

The Ewe Stone will appear in Mark Goodwin’s forthcoming collection from Longbarrow Press.

The Wild Culture Scribbler's Questionnaire

by Mark Goodwin

1. What is your first memory and what does it tell you about your life at that time and your life at this time?

The red quarry tiles on the farmhouse kitchen floor of my childhood home. My very small hands feeling the warmth of the sun streaming in over those tiles . . . and outside beyond the open kitchen door, the sun glinting on the cobbles in the yard. Even then — ‘outdoors-and-indoors’ — how those are apart and yet together, I could feel that . . . and now as I pass through what I hope is the middle of my life . . . dwelling, shelter and the weather and exposure to the elements, hunger and physical bodily power, and moving through weather and across ground . . . these I fear and love equally.

2. Can you name a handful of artists in your field, or other fields, who have influenced you — who come to mind immediately?

Ted Hughes, Werner Herzog, Vasko Popa, Kraftwerk, Sylvia Plath, Peter Redgrove, Andrei Tarkovsky, Gary Snyder, Penelope Shuttle, Pink Floyd, Geraldine Monk, Peter Riley, David Lynch, Fedirico García Lorca, Akira Kurosawa, The Beatles, Alice Oswald, Peter Dent, Norman Jope . . .

3. Where did you grow up, and did that place and your experience of it help form your sense about place and the environment in general?

I grew up on an arable farm in South Leicestershire. That place that held my childhood tight also threw me away to other places as a grown up. That place, that valley, its fields, ditches, trees, creatures, ponds and its stream . . . its various places . . . those grew my fascination for place . . .

4. If you were going away on a very long journey and you could only take four books — one poetry, one fiction, one non-fiction, one literary criticism — what would they be?

They might be: Peter Redgrove’s Collected Poems – many of these poems I’ve already read many times; John Cowper Powys’ A Glastonbury Romance –I’ve only read this once, well over a decade ago; Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain – I don’t know the Cairngorm mountains as well as I know the West Highlands, I intend this book to be the bedrock for my meeting more fully with the Cairngorms; Ted Hughes’ Winter Pollen – If I took this then I’d also have to have a copy of Coleridge’s Christabel & Plath’s Ariel to go with it). It all depends very much on where I was going, and how I was travelling . . . for example: I wouldn’t attempt to carry Redgrove’s Collected and Powys’ A Glastonbury Romance (a brick of a book) on my back over Munros in The Scottish Highlands.

5. What was your most keen interest between the ages of 10 and 12?

Building, with my school friends, extensive dens from straw-bales, out in the stubble fields or in my father’s straw-barn, after school and at weekends. These were complicated systems of tunnels and igloo-like domes, with all the cracks stuffed with loose straw to make pitch blackness. Tig in these tunnels, with torches, and sometimes without. And the rope-swing in the straw-barn: A fifteen-or-so-foot length of blue polyprop wagon rope, with, at intervals, knots to grip, and at the bottom a fat straw-wadded knot to sit on. This rope (doubled into two strands) was larks-footed to a steel hook and chunky chain my dad had strapped round one of the barn’s steel roof girders, right up near the apex. This ‘ride’ required a four-foot vertical drop off a beam on the barn wall before the begin of the swing, the arc of which would take you right up to very nearly being able to touch the cob-webbed corrugated roof . . . and then at the end of the return swing, so as not to smash back into the wall, you had to tug hard on the knots so as to lift your feet above your head, getting your body upside-down but away from the impact. Just before I launched into this swing for the first time was also the very first time I felt my tongue stick to the dry roof of my mouth. The inverted question-mark of the steel hook and the blue rope’s curve towards me, back from that attachment. The leap. The strands of gravity rushing through my guts. The grind of the chain on the girder still rings in my brain.

6. At what point did you discover your ability with poetry?

When I was about sixteen. I started writing about climbing and mountains. Friends, and later a sixth-form teacher encouraged me. But now that I look further back, I can see that as a child I always loved the feel and shape of sounds in my mouth, and how those sounds made shapes in my mind ...

7. Do you have an ‘engine’ that drives your artistic practice, and if so, can you comment on it?

The engine is my physical body . . . how it carries my mind around, and how my throat can make sounds, and my ears can feel that . . . it is lungs, breathing, and it is pumped blood’s rhythms . . . it is touch, and all the senses, and the sense of balance . . . of swaying but staying on an edge between a thought and a place . . .

8. If you were to meet a person who seriously wants to do work in your field — someone who admires and resonates with the type of work you do, and they clearly have real talent — and they asked you for some general advice, what would that be?

Don’t read books on how to climb trees. Let the tree and its shapes, and the shapes it makes you make be the first lessons. Once you’ve slipped and fallen off a few times, and once you can feel the possibility of being fluid as you climb, then you must start reading books about how others have done it and do it, intend to do it, hope to do it, and even pretend to do it . . . and you must agree, and you must disagree, and you must especially be confused and not sure . . . and you should try very hard to become fully aware of and accepting of fear . . . your own fear especially, but other people’s fear too . . . But above all, fall in love with climbing the tree, and indeed climbing various trees, on still days, windy days, in sunshine and even at night . . . and let nothing else relating to your practice be worth more than that falling . . . ah, yes, also, and possibley as important as the love: take nothing literally, for the literal is the origin of – and also the ultimate – superstition ...

9. Do you have a current question or preoccupation that you could share with us?

The preoccupation is FEAR! In this Time of The Clown, my question is already shared; it is the question many people are now asking: will the returning threat of facism, and the threat of spreading war subside? Hopefully, this bizarre, nasty moment we are all now making is just some kind of mist . . . is some kind of thickening bad dream that will eventually blow away... but it is probably cowardice to think that . . . certainly cowardice to leave it at that. Much more hopefully: could this Clown Time lead towards humans finally breaking away from their ancient cycles of violence? . . . Is it possible for humans to evolve psychologically in such a way? What a hope! . . . There are two kinds of fear: useful, energizing fear . . . the kind I engage with when I climb . . . and this is an easy fear, that empowers if you embrace it carefully . . . it is a negotiation. There is also a miserable kind of fear, the kind that gives us nothing and just takes from us. That kind of fear can only be run away from, or come up against. We cannot negotiate with that miserable fear. To do something about that miserable fear means dragging one’s self towards what one really wants to, or in fact needs to get away from as quickly as possibel. Am I a coward or not? . . . I’m afraid just at this moment it looks like I could be tested on that before too long . . .

10. What does the term ‘wild culture’ mean to you?

It seems impossible. The word ‘wild’ is a product of human culture and comes nowhere near to engaging with the beyond-human forces and beings it attempts to categorize. Culture is something humans make and, in the part of the world I live in, tend to believe other animals (so-called wild or otherwise) cannot make. I’m a human animal, and so of course I am of culture . . . and of course I know culture is vital. But, ‘wild culture’, yes, that’s impossible! And, it is possible that some person imagined as ‘Me’ believes in all the gods, ancient especially . . . and if I do, then ‘I’ praise them over and over again for the impossible, and especially for what ‘We’ weakly call the Wild.

11. If you would like to ask yourself a final question, what would it be?

I don’t want to! Not just yet. I’m frightened to ask a final question. I just want to keep on with questions. Death will meet with me at some point, so I guess a or the or my final question I ask (before the bacteria of my body lose their dwelling place) will be fairly close to that event. Might be tomorrow . . . but I do hope not . . . but, well, could be . . . and there it is . . . I accept that . . . ah, that’s how it happens . . . that’s how this life thing ends . . . uhm . . . I’m now in danger, in danger of heading towards some kind of answer . . . don’t like answers . . . well, not final ones ...

MARK GOODWIN is a writer, climber, balancer and stroller who lives on a boat in Leicestershire, England. He has published five poetry collections and four chapbooks, and his poems have appeared in rock-climbing guidebooks published by the British Mountaineering Council, The Climbers’ Club, and Ground Up. Mark's next book with Longbarrow Press, Rock as Gloss, is a poetry collection which includes fiction — and images by Paul Evans. [Mark's site.]

PAUL EVANS is an artist and climber based in Sheffield, UK. He received the Eyestorm Gallery Award for painting (2007), selection for Leverhulme Trust Artist’s Residency, Cardiff University (2011), and winner of the Wake Smith Painting Commission for Sheffield Year of Making (2016). Further examples of Paul's paintings can be viewed here and here.

Add new comment