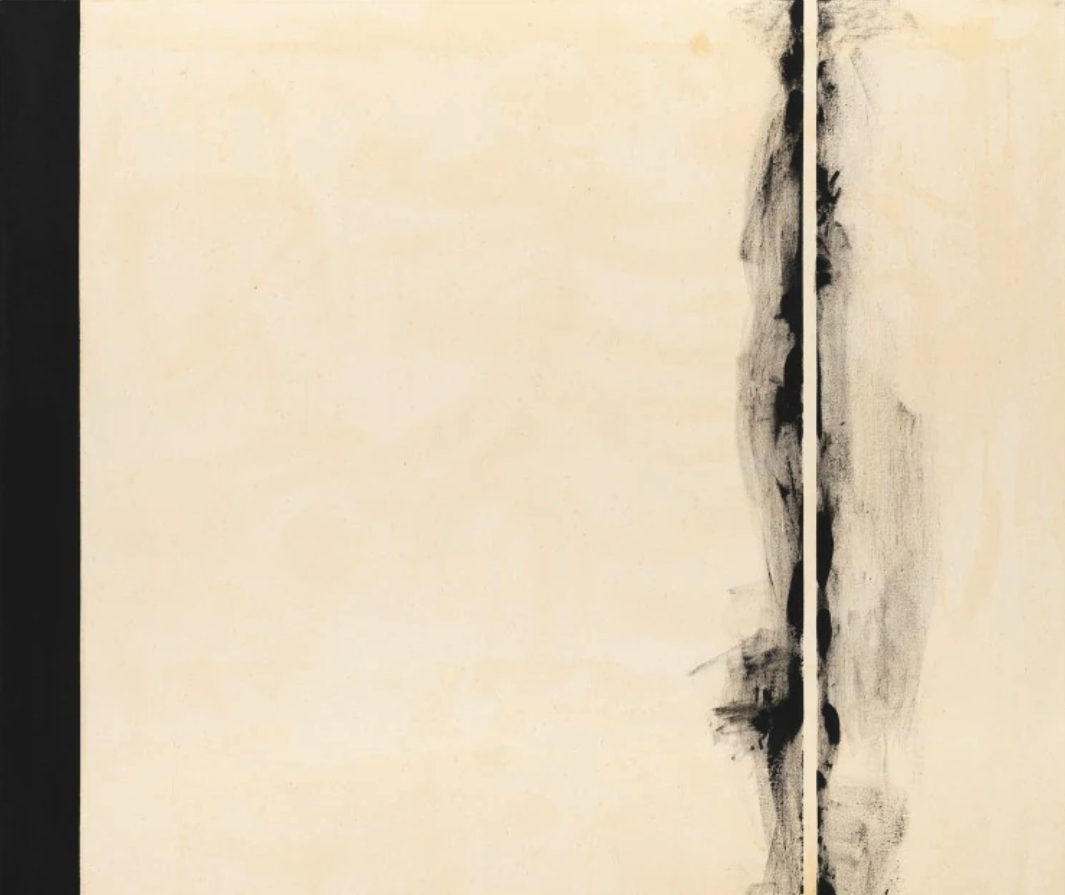

'Evening Prayer,' by Tim Wilson. 2021.

WHITNEY SMITH I'd like to start our discussion with the following question. How can we open a dialogue about the experience of religious faith and/or spiritual practice between two opposing sets of people: those who have a commitment to a faith or spiritual practice, and those who are turned off by that language or have never been engaged by it — but may be open to exploring the human realms it describes?

TIM WILSON To kickstart my thinking, I just put that old chestnut, “Can people be good without God?” to my avatar, Siri. And She (He? It? They?) came back in about half a second with 'Yes and no...'

SHAWN WINSOR We’re firmly in the land of 'yes and no’ here, so perhaps one good way to appeal to a community of people who are agnostic – even hostile agnostic or indifferent — is to share interesting and important ideas that are relevant to those who have faith and those questioning faith, or without a faith. An example might be the field of spiritual neuroscience, or, as some say, neuro-theology, which looks at the roots of spiritual consciousness in the material substrates of the brain. It proposes that our consciousness is determinative of a spiritual life: whether we should have one, and if we do, how it manifests in real terms. Because of its materialist approach, I can imagine people who are without a faith, or agnostic, who might find that an interesting way to come at the question. And those of us who have faith, I think, would also find that interesting. It's like the meeting place of science and spirituality. And so, like any meeting place between these two communities, this is where they can have a conversation without feeling that it's loaded with small-p political implications.

Some say that the concept of the spiritual is that it’s a reflection on inner experience at its most stripped down.

TIM WILSON Do you mean, for example, deep relaxation that shows certain brainwave patterns?

SHAWN WINSOR It could be. There are also technologies used to address the question more directly: functional MRI scans done of the human brain when people who self-identify as having a faith are reading sacred or spiritual texts. The scans reveal that a unique area of the brain is consistently fired up during that activity. But not in the same way by other related activity. Some suggest this shows the existence of a kind of spiritual response in us that our brains are hardwired for. Others who tie the spiritual into the notion of ritual would say this unique brain activity is evidence of the human desire for ritual, which is as old as us human beings. Northrop Frye, the great Canadian scholar, said that ritual and myth proceed language — that our need for ritual is tied into this notion of the sacred; that ritual is a spiritual response to our environment; importantly for him, one that includes other human beings. These are some avenues of attack in this area if we want.

TIM WILSON I discovered, just yesterday, a poem or meditation by the late Richard Wagamese, the Indigenous poet and writer. In it he says ceremony doesn't change you, you change you. But ceremony brings you to the place where you can do that, or it traces the pattern of that. So it’s been a huge attraction in my own spiritual path, in the music of the Church, for instance, or in the language of T. S. Eliot.

DAVID WALSH In the way liturgy and poetry have a certain spiritual ring to them?

TIM WILSON Yes. Poetry, in particular, for its quality of distillation, economy, compression — like the making of a diamond. And liturgy, especially if it’s connected with music — to my mind the most spiritual of all the arts. Though music is so untranslatable, ineffable, in a sense unknowable. As someone famously said, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”

WHITNEY SMITH Poetry draws on language abstractly, as do song lyrics that pluck us out of our present state of mind and steer us somewhere else. Liturgy can do that, too, inviting us to come out of the everyday and into ritual space. This is one reason people are attracted to going to church, I think, because it takes them away from the worldly mode from which we all need relief every so often. It’s not just about religious spaces, the secular space of a yoga session — or any sort of physical or mental practice where effort is expended to concentrate — is ritualistic and offers relief, too. In all these various ritual spaces there is the possibility that a switch is turned on and what follows is the shift into different perceived states of consciousness. However minor that shift, the fact that there is movement from one place to another in such situations tells us we are alive to transformation, since movement keeps us on our toes for the next best thing. Dancers know all about this.

SHAWN WINSOR Some say that the concept of the spiritual is that it’s a reflection on inner experience at its most stripped down: the product of a kind of self-psychoanalysis, a self-reflective, and perhaps self-reflexive experience of and relationship to that which comes in from outside. It's not just an immediate reaction to sensory stimulus, but it's a deeper reflection on elements of that as they related to oneself.

Rembrandt van Rijn, 'The Return of the Prodigal Son,' c. 1661-1669. Oil on canvas. (262cm/103in x 205cm/81in). Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

TIM WILSON The change of consciousness you're describing, Whitney, reminds me of something the late poet Mary Oliver said. Her poems are widely loved for their close observation and their deep relationship with the natural world. ”Paying attention”, she said, “is prayer.”

DAVID WALSH To the list of important forms of prayer and ways of living in the present moment, I’d add contemplation and meditation. But on the subject of paying attention, a book by the native story teller Tim mentioned, Richard Wagamese, has a lot to offer. Here’s an example: “I am constantly surrounded by noise: TV, texts, the internet, music, meaningless small talk, my thinking. . . So I cultivate silence every morning. I sit in it, bask in it, wrap it around myself, and hear and feel me. Then, wherever the day takes me, the people I meet are the beneficiaries of my having taken that time – they get the real me, not someone shaped and altered by the noise around me.”

Whitney, you’ve had a lot of experience reflecting on the spirituality of the land, the spirituality of nature, and we know important theologians, such as Thomas Berry, or the poet, Wendell Berry, who relate their spirituality to the land. If people live in the city and they're surrounded by high rise towers, and don’t have much chance to experience the natural environment, then it may not be easy for them to relate to nature.

WHITNEY SMITH Getting away from my busy self in the city (where I am happily engaged, in work and family and society) to go on a canoe trip for a week or two, this puts me in that ‘alive to transformation space’ I spoke of — similar to meditation, being inside a church, engrossed in a powerful conversation with someone, taking a hallucinogenic drug, and so on. After a few days on the canoe trip, I become aware of a sort of curtain separating me from a particular potential, beckoning to revealing itself. In my psychic gut, behind this curtain is a deeper expression of what I might experience in the present moment. And if I am able to open to it and go with it — to what, I'm not exactly sure — then more is revealed behind the curtain. In the wild, obviously, a big part of that is a sense of the non-human.

What I’m describing makes me think of Spinoza's idea of boundless totality, the singularity of a spiritual existence in which God and the human and nature are not different or separate things, but co-exist within the same place. For me, when I’m in the untamed environment away from civilization, what's on the other side of the curtain is an image or sound of the wild speaking — trying to get the attention of cultured me. In that state of awareness there is less separation of me in here and that out there. Less division, more sum total.

SHAWN WINSOR I wonder if the challenge for us here is one of definition primarily. I think if you take someone who's agnostic, atheist, and you ask them to describe the experience of walking down a wilderness trail from one town to another along a meandering river on a Fall day, I imagine their account would be strikingly similar to many aspects of yours if you were to have had that same experience and described it. And yet, the way each would define it ultimately, past the what into the how, is where we would start to disagree, perhaps distrust or even denigrate the other person's viewpoint because that viewpoint is predicated on assumptions we find foolish. We go so far together along this path of understanding and knowing until we move past the point of describing to defining. So maybe that's the impediment we can find our way around — doing a better job of explaining these things without using the language of religion.

DAVID WALSH Because religion is really a human construct, no matter what religion it is, we have to realize there's a human element there — the same ego and light and dark side that we're going to find in any human construct. Hopefully, the spirit's moving within our religion, but often it faces a dark side as well.

SHAWN WINSOR Yes.

TIM WILSON But I can also be in magnificent, so-called 'pure' nature, and be dragging along my quotidian consciousness: like getting envious of the guy with the expensive backpack in front of me. In an early issue of the print version of The Journal of Wild Culture there was an interview with William Irwin Thompson in which he talked about nature, including the city pavement, the metal and high-tech toys and all the rest of our constructions. That's nature, and the 99 million names of God sing in all of it. Based on that, I’d say we need to be open to expanding the categories of the sacred.

Barnett Newman. The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani. “First Station,” 1958, Magna on canvas. [o]

SHAWN WINSOR The constructions we bring in – social, material, what have you — lens our experience of the sublime, but eventually they are eclipsed and we see differently. In the film The Octopus Teacher, you don’t have to be a fan of cephalopods like me to find the story fascinating — the great learning for the filmmaker, the narrator, is not from the octopus per se, but his immersion in the underwater environment, every day for months. This immersion eventually gets him to the point where he stops seeing the difference between himself and the particular environment [he was in]. He starts to see how he is part of that environment — which seems obvious — but you have to see the film to see how integrated he became into it. He was like, “These creatures stopped seeming other to me. They became part of who I am and how I am in the world, and I began to see the connections between all living things.” I think it can take that kind of immersion over a long period of time to shed the shackles of urban or modern life and all the other things, including religious life, that we surround ourselves with to keep that other world out… or use to create a simulacrum of it we can control.

TIM WILSON I remember William Irwin Thompson talking about Saint Columba and the Celtic tradition of spirituality. The 5th and 6th century monks of Iona and Lindisfarne used to stand out in the waves to do their meditations, and the seals and other sea creatures would gather around them. Now that might just be a fable, but the idea is of a closer connection with non-human Creation, and that connection got somehow lost in the Roman brand of Christianity.

WHITNEY SMITH I want to bring us back to how we use language in this hypothetical dialogue about religion and spirituality between people of faith and those who are agnostic or non-believers. David, you used the term “spirit moving in us,” and though I have a sense of what you mean by that, and am curious to know more, I have to translate it a bit for myself. As we’ve implied, there are other people who are on guard for certain kinds of, for lack of a better term, religious-speak, that this phrase might fall into.

DAVID WALSH The indigenous people use the term ‘spirit’ a lot — ‘the great spirit’ moving in the world, or in the ‘spirit world’. Sometimes it's easier to talk about the indigenous experience rather than our own experience since some people are more open to hearing from indigenous voices because there is so much cynicism today about mainstream religion.

WHITNEY SMITH Yes. We’re more open to language that has no association with experiences of indoctrination.

TIM WILSON I find myself more inclined to say “Great Spirit” than “God," though that risks appropriating Indigenous tradition. I actually prefer, if I have to try and name the divine, to say “Great Mystery.”

WHITNEY SMITH In the Muslim tradition there must be no literal depiction in imagery of the divine being. The result has been some spectacular and influential architecture and interior design that celebrates the mystery of the divine without pointing at it.

TIM WILSON And the Jewish tradition forbids naming it . . . “it”?, “that”?, “he”?, “she”? . . . with anything more than “Yahweh”, which the Catholic contemplative Richard Rohr points out isn’t even supposed to sound like a word. It’s just the sound we make of a huge breath in and out. The sound of our life.

SHAWN WINSOR The four letters that form Yahweh are each deeply symbolic, handed down by Moses. The word itself has an interesting history; one that includes it too eventually being prohibited for being too sacred – the unfortunate side effect of its popularity. Adonai is most commonly used now, I think. Christians replaced the Hebrew letters with their opposite numbers in Latin and rebranded Him 'Jehovah.'

So, digging a bit deeper into the language: How about soul? It seems to be one of those ideas that straddles both religious and non-religious worlds. People believe in ensoulment, or the fact of soul, even if they don't have a faith or a religion. It seems to be a concept that's both deeply humanist and strongly connected to spiritual traditions too – although not every faith identifies a soul. Maybe that's where we all meet, in the soul space.

I learned it was a question of profound anxiety for her, even though she had a very strong faith.

WHITNEY SMITH I want to pursue that, but I think it’s important to know what your definition of a humanist is.

SHAWN WINSOR Humanism is a celebration, a belief in the essential features of human existence as worthy of study, worthy of aspiration, worthy, even, of celebration itself, up to and including humans being the kind of peak pinnacle expression of life in the universe.

WHITNEY SMITH You were saying that the concept of soul is both humanist and connected to spiritual traditions.

SHAWN WINSOR So how about this for complicating it further. In Judaism, as I understand it, it is believed that every created thing has a soul: humans, animals, plant life, even pebbles on a beach. Humans’ souls have five manifestations, one of which they share with all the other created things while the others have specific roles in relation to God. The first of these gets closer to, I would suggest, a quasi-humanistic view of the soul that I see from Spinoza (who, not incidentally, was a born a Jew and died an atheist) that soul is this energy that all organic matter and all living things have in them; sometimes called ‘world soul.’ That's the holy spirit in a faith context; that which ties everything together, or ties us to the unitary, the one.

WHITNEY SMITH By quieting ourselves and listening for world soul, we become more alive to ourselves.

DAVID WALSH I think the word ‘alive’ is important — being fully alive and experiencing that aliveness, as much as understanding the theory behind it.

SHAWN WINSOR I was thinking that the soul, within the context you just explained, Whitney, is much the way I did a moment ago. But how would you explain it if you didn't have a faith, in the scenario you just presented? So, you're out in the world and you feel more alive, which is attributed to your soul awakening, or prompting you or having been stimulated; what's the connection there?

WHITNEY SMITH If I didn’t have a faith? Maybe this will help. Though I’ve spent a lot of time singing in church choirs, I’ve never been spiritually moved through what is presented in the liturgy, never had what some might call a faith experience — though I’d love to. On the other hand, the music has certainly brought me closer to something divine or other worldly, maybe since I am a musician, or because the spiritual experience in the community of musicians giving praise through the music — which I can do as well when I play rock or jazz — was in a format I could understand and was open to.

Somewhat related to this is that my sense of what God is, or what soul is, comes from a belief that I am participating in a kind of transaction or contract of give and take with the world, and the currency of paying attention to the details . . . of being a good person, being considerate of others and aware of how my own deficiencies might harm or ignore people I come in contact with. I’m not sure I can answer your question about the connection between a person who does not have a faith. My view of how the world works is tied up with a faith personal to me and always evolving.

SHAWN WINSOR It may not have an answer. I proposed it and now I'm tearing it apart, saying that there's perhaps a meeting ground between those who have a faith and those who don't formally, and in that meeting place is the soul. Then you presented a scenario where they may meet and I challenged it by saying, well, define for me how that soul is manifest for someone who doesn't have a faith. That is, if you were to explain to someone who doesn't have a strong faith tradition or claim to have a faith, what a soul is, and if they had been willing outside of any nature context to entertain the possibility that they had one, and you use the example of nature that you just gave to illustrate, how would you explain the soul in that sense? What is the soul there? Why is that the place where the soul is activated and how does it manifest? How does it animate us in that unique way?

Caravaggio, 'The Incredulity of Saint Thomas,' c. 1601–1602. Oil on canvas. (107cm/42in x 146cm/57in), San Souci Picture Gallery.

WHITNEY SMITH I would explain that it exists in a place between beauty and mystery. To submit, or to open, to the poetry of ritual in whatever form, or seek out and receive art that changes the way we think and feel, these are doors to pass through into my version of what you’re describing as soul.

TIM WILSON I did a radio program in the late 80s with the mytho-poetic men’s movement leaders Robert Bly and James Hillman, who said that one of the properties of soul is that it takes you down and in, not up and out, the way we normally conceive of spirit, as an aspiring arrow arching in the blue. The psychic qualities and trajectories of spirit and soul are different. When I was sorrowing over certain losses in my life, Bly wrote me a lovely note to say I was like “water running downhill, but going somewhere”. I relate that to paying attention. Not trying to transcend, evade or rise above, but to go more deeply in. For me, moving “down and in” also means less quoting of other people’s wisdoms, as I’m too often inclined to do, but minding, and mining, more of my own.

SHAWN WINSOR I want to pick up on both of your points, that's great. I’m a big fan of Bly. I like the way he formulates that, except the difference for me is that the experience you're describing, Whitney, is self-obliterative — we lose track of self and become aware of world soul or the larger thing around us. Some get it looking up at the stars, others from looking at a beetle on a leaf, but in both respects it’s that sense of the immensity, the power, the infinitude — or even the finiteness, finitude — of existence. However you want to frame it, it is large concepts that make our sense of self shrink and expand simultaneously: the allness of us shrinks and the bigness of us expands down and in. Where Whitney stops thinking about Whitney, and you, Whitney, become all the other things that you're part of and capable of, and will go back to when you die. That process is what I think happens. And maybe that's the connection between soul and world. The way that everyone can experience it without needing to use that religious language; it’s outside of faith explanation. But, having said that, for me the connection between soul and world is a deeply spiritual one.

WHITNEY SMITH The only real conversation I had with my father about what lies beyond everyday life was when he was dying of lung cancer and had a few months to live, at 63. He was reading letters that his father had written him, which we both found very moving, and he asked me, “Do you think there is an afterlife?” He wanted to know if I and others close to him believed in that. He had been a dutiful warden in our local United Church [of Canada; progressive Protestant], and though I would not call him a religious man, he was very committed to the social function of his church community. Yet suddenly he was asking a question that was surprisingly spiritual and intimate.

TIM WILSON Asking “where am I going?”

WHITNEY SMITH Yes. “What’s next?”

SHAWN WINSOR It’s the kind of the question I’ve been asking, having buried three people I know last year, one of whom is my mother, another a very good friend. None of them wanted to explicitly address this question, and two of them were people of very strong faith. It's one of the scariest things you could possibly ask yourself, I think, whether you have a faith or not. Through my work I've been at the bedside of a number of strangers who've died, and I’ve talked to my father about this, who, as a minister, has been at the bedside of many, many more than I have, and he said it's a question you don’t ask, unless invited.

WHITNEY SMITH However, if you are invited to ask it, there must be a careful framing of the question. And, that it be an easy question to answer.

SHAWN WINSOR “Do you know where you're going?” I actually made the mistake of bringing it up with my mother when she was dying, and when I did I learned it was a question of profound anxiety for her, even though she had a very strong faith. It's the last question left, the last one there will be. You could spend a life of faith in practice but maybe there's always a little part of you that's just not sure.

You spent a lifetime’s worth of engagement in this project, and now it's coming to a head. I know that feeling. I was given a false terminal diagnosis a number of years ago, and I was able to manage the anxiety around it quite well. However, whenever my mind came to the question of what happens after I die, I was like Nietzsche's man who stares into the abyss: Be careful, as it might stare back into you. Immediately, I would just pull back. It is that kind of question! I'm like, I cannot even begin to go there until I absolutely utterly have to. And I believe in my mother's case, when she had to, moments before she died, is when she did.

Jean-Francois Millet, 'The Angelus,' 1857-59. Oil on canvas. (55.5 cm/21.9 in × 66 cm/26 in).

WHITNEY SMITH In our attempt to create some opening points for our readers, and as we bring this to an end, I’d like to ask you for a final reflection.

DAVID WALSH I was trying to get our intellect and our inner wisdom connected, and looking at how to be fully alive in this life we are living.

SHAWN WINSOR I'm going to make again the same point that I made in the beginning, just because I think it gets at the question you've been asking. I say this following on what David just said, which I thought was wise enough that we probably could have left it right there. The project is, as you've described it, to find a way of discussing these issues with people who don't come from a faith tradition — who don't self-identify with that — and I found some of the most robust parts of the conversations we've had over the last month or two have been when we've been sharing our personal experiences about our own faith journey, or how we arrived here, but also our own doubts, etc. I still think that's a valuable way to get at this, rather than trying to ventriloquize the mind of someone who doesn't have a faith — and figure out what's the way in there. I imagine that the curious will find a way in through personal story or experience or through the expression of the same kind of uncertainties — intellectual, definitional, or even just deep-seated doubts through life experience — that we and others in faith have. That's the common thing that we share and that'll be the way they find their way into this.

TIM WILSON Who was the architect who said God is in the details?

WHITNEY SMITH Mies van der Rohe.

TIM WILSON I like that a lot. As for myself at this late stage of my life, I’m finding that paying loving attention to the so-called “little things” opens up into what you so well described, Shawn, as the “allness” and “bigness” of those same things. Those holy things. ≈ç

FURTHER READING

Hick, John. The New Frontier of Religion and Science: Religious Experience, Neuroscience, and the Transcendent. Springer, 2006.

Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four essays. Princeton University Press, 1957/2020.

Watts, Alan, The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, Knopf/Doubleday, 1989.

Seneca, On the Shortness of Life. Penguin, 2005.

A. C. Grayling, The Good Book: A Secular Bible. Bloomsbury, 2016.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher and Editor of the Journal of Wild Culture. He is the co-founder of a choir called B-Xalted! He lives in Toronto.

DAVID WALSH is a businessman, activist, and social enterprise leader. Along with his work in the fields of affordable housing, social justice, and developing resource centres for disenfranchised citizens, he has a strong interest in connecting faith and social justice. He lives in Toronto.

TIM WILSON is a documentary film director, radio producer, essayist and photographer. In several decades of producing profiles, he has interviewed many notable figures of our time. Relevant to this interview is his feature documentary, Griefwalker (The National Film Board of Canada, 2008), about a man who turns the act of dying into an essential part of life. Tim lives in Bear River, Nova Scotia. View his site.

SHAWN WINSOR is a bioethicist working in clinical practice, public policy, research, and education. He co-founded the ethics programs at two of Canada’s largest fertility clinics and was Director of Canada's oldest clinical ethics program at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Toronto. He is a member of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Joint Center for Bioethics at the University of Toronto. He lives in Toronto. View Shawn's site.

Add new comment