There are certain artists about whom writing is a fairly straightforward task. And there are others whose work seems to resist the controlling voice of the writer – not only that it constantly overruns attempts at definition or containment, but that it never quite seems to be possible to get a grip on it in the first place. Falling into this latter grouping are the paintings of Kerry Brewer, who has two simultaneous solo shows in London this September. I've written extremely badly about Brewer's work before (on the occasion of her last exhibition – on Cork Street in 2010) but I feel like this issue of control might be a more fertile approach than the abstract blather I spouted last time.

For Brewer's work is about as highly controlled as painting gets. “Nothing is ever arbitrary within the painting,” she tells me on my second visit to her south London studio, where Otto, her vast Scottish deerhound sprawls grandly on the floor. “Everything is there for a reason.” This means that the creative process is an extremely slow one: every work is produced one at a time – “each a project in its own right with its own unity and clarity” – and takes between three and eight months to complete.

Brewer begins with a narrative – “a very simple narrative”. She then either sets up or goes out and take photographs, which are then collaged together using Photoshop, removing certain elements, adjusting composition, gradually removing the clarity of specific reference. This can take weeks – sometimes the image “dies” and Brewer starts all over again. The aim is to produce something that's “half way between the knowing and the not knowing” - that semi-figuration that so allures and confuses.

It is at this stage that Brewer first begins to plot out the composition of the work. “It's one of the things I spend most time on,” she says. She cites Matisse's Still Life with Magnolia and Théodore Géricault's The Raft of Medusa as examples of near perfect composition, in which the eye of the viewer is led carefully around the painting. In The Raft of Medusa, for example, Brewer notes how “the only place where your eye is led out of the canvas is following the line of a dead body”.

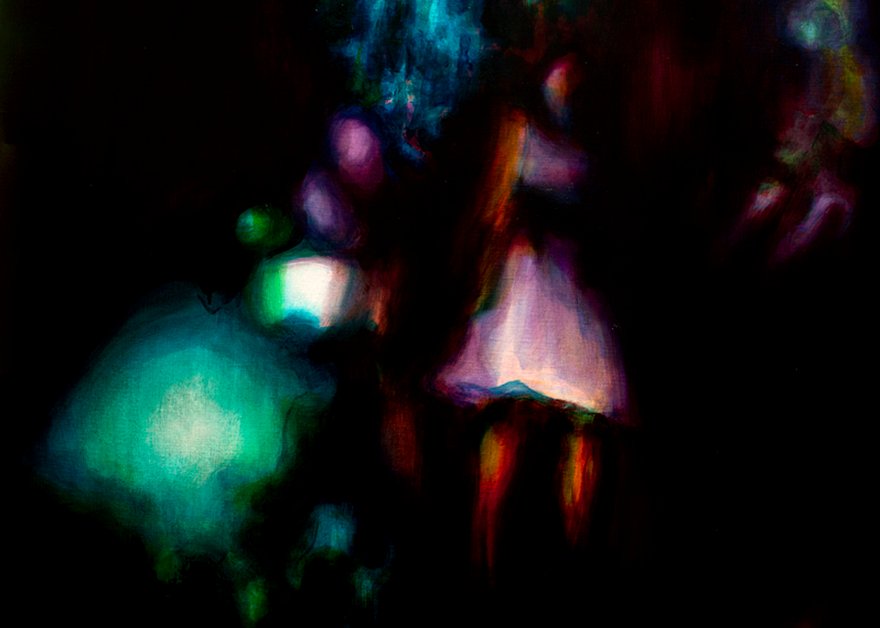

In her own work, Brewer navigates a delicate balance between harmony and disorientation, one that echoes current thinking in neuroscience. By building up layer upon layer of transparent glaze, she creates a kind of echo effect – evoking what she describes as a “drunken, mesmeric, woozy feeling”. This is a product of Brewer's painstaking painting process, which is rooted in drawing and reliant, she says, “on the ability to control the mark”.

These are works that demand one spend time with them. They cannot simply be 'consumed'.

But it is also subject to the external authority of the work itself. After every brushstroke, Brewer slowly walks away from the work “to watch how each mark changes things”. The resulting impression then dictates the next course of action. And this is where the tangled issue of control is most evident. For, in a sense, at these points it is no longer Brewer who is in control of the decision-making, but the demands of the painting. “There are two types of painters,” she tells me: “those who impose their vision on the canvas, and those who follow what the painting is telling them to do – and I am definitely one of the latter. I am the minion to the paintings; they lead me further than I believe my own imagination is capable. They are often surprising, but they are always right.”

The result for the viewer of this shifting balance of power is an effect akin to that of tiredness, tears, drunkenness or concussion – “something that obstructs the ability of the brain to read the surrounding environment”. Brewer compares the experience of viewing the works to “the lurching sensation of suddenly seeing a deer in a forest” – something is suddenly revealed and then just as quickly taken away. On each of my visits to the studio, different elements of certain paintings stand out – troublingly, intriguingly. In one work is what looks a little like a shell, semi-submerged in darkness to the far left of the painting. “It sits there in the peripheral vision,” Brewer explains, “creating a kind of cognitive disturbance.”

This is instructive. As Brewer herself says: “If there is one thing that ties all the paintings together it is this playing around with perception.” She cites the work of experimental psychologist Richard Gregory as influential in helping her to think about these ideas, although they were present in the works even before that. What the works are doing is playing with the “assumptive nature of perception” – the necessary process by which the brain fills in gaps in our vision based on assumptions about the data it receives from the eye. Whilst this is a fundamental aspect that enables our vision to function at all, it also opens up loopholes of unreliability, which Brewer's paintings then exploit to juddering, lingering effect.

This focus on the mechanics of perception and composition as one part of the framework that exists within and supports the finished painting, seems to me unusual. Brewer agrees. “I don't think composition really gets talked about any more.” Part of this is due to the illusion of finish (“The final thing that you put on a painting is the veneer of magic that conceals the layers of struggle.") but also to a shift in the way we approach the visual. “Today,” says Brewer, “there is more of a fascination with the final layer. People are used to seeing a painting in an instant and getting all there is to get” – just like any other image, in a society increasingly saturated by the visual. But painting is different. Or, at least, in Brewer's hands it is.

These are works that demand one spend time with them. They cannot simply be “consumed” digitally (in fact, they don't translate online at all). “I'm interested in longevity in a painting,” Brewer explains, and I think that's really unfashionable.” That issue of longevity – of a repeated, long, slow experience, is crucial to both the production of and the encounter with these paintings. “You need to watch them,” says Brewer tellingly. “They move, evolve, change.” If writing, by contrast, enacts a process of fixing, maybe that's what makes Brewer's work so tantalisingly difficult to describe.

Kerry Brewer – Have Love (Whoa Baby) Will Travel is at The Unity Gallery, London from 16th-28th September 2013

Kerry Brewer's drawings are at Arcadia Cerri, London from 20th-28th September, 2013.

www.kerrybrewer.net

Image credit: © Kerry Brewer, Laddermain (detail) 2012. Photography with thanks to David Brunetti.

The artist also wishes to extend her thanks to Otto, for all his hard work in bringing the two exhibitions together.

Add new comment