The link between sight and understanding is long-established. From the Enlightenment and the concept of clarity, to vision, foresight, and perception itself (as feeling and observation, learning and knowledge) it’s a metaphor so deeply inscribed into both our language and our thoughts that it lingers on, largely unobserved.

It is in this light, as well as that shone into our heads by recent developments in the field of neuroscience, that Affecting Perception “looks at the relationship between art and the brain”. Taking place this March at the O3 Gallery in Oxford, the exhibition has been conceived by the AXNS Collective, a curatorial collective of recent arts and sciences graduates, and features work across a range of media, but with a central focus on the visual arts.

The majority of the artists included in the show have brain disorders of one kind or another – Asperger’s, migraines, dyslexia, dementia – and the aim of the curators is to “explore how changes in the brain affect an artist’s work”. Importantly, this is not part of a move to explain creativity (or explain it away), but rather to “widen the debate” around the interpretation of art. Largely, I think, AXNS have been successful, and Affecting Perception excels as both an interesting insight into the workings of the brain and an art exhibition of interest and variety.

The O3 Gallery is an unusual space – housed in a circular stone space inside the old Oxford Prison, and spread over two floors around a pair of curving staircases – but the curators have done well to overcome the potential challenges. Setting the tone is a video of cranial surgery recorded by one of AXNS curators, in which the subject, Marc, is shown a live video of his visual cortex on screen, thereby forming a witty, disconcerting, neurological mise en abyme.

The danger, as ever with art-science crossovers, is that the art becomes merely illustrative.

Continuing this playfulness is Yoshimasa Kato and Yuichi Ito’s film of a 2007 installation in which participants can see their own brain waves – recorded using EEG and played, writhing and wriggling, through a speaker filled with potato starch. Elsewhere, Jason Padgett explores order through exquisite mathematical diagrams (his perception dramatically changed following a brutal attack by muggers). Tess Gammell’s drawings capture the tissued delicacy of the human brain, visualising a kind of gently crumpled coming together. Meanwhile, ink and crayon drawings by twentieth century author/illustrator Mervyn Peake bring a kind of shaky clarity, especially in Grotesque Head Maeve, where definition emerges from some deceptively rudimentary mark-making.

The danger, as ever with art-science crossovers, is that the art becomes merely illustrative, rather than standing on its own as Art (however problematic that capitalised concept might be). There are moments when Affecting Perception drifts towards this kind of territory: JJ Ignatius Brennan’s migraine pastels possibly, and Nicholas Wade’s brightly coloured illusory trickery (although Wade, a psychologist, could certainly cite Bridget Riley as an example of such illusion as Art). And there are also moments when the biography of the artist might be seen to overshadow the work itself: discussion of George Widener’s technique as “relaxing” or as an “outlet” for expression alerts us to the tricksy spectre of Outsider Art.

Such moments don’t so much detract from the exhibition as demonstrate the difficulties involved in navigating this kind of terrain. If anything, they serve to emphasise the brilliance of William Utermohlen, whose two self-portraits are, for me, the highlight of the exhibition. I’ve seen his work before, both as part of Wellcome’s 2012 Brains show and in a career retrospective at GV Art, but it feels especially powerful in this context. Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1995, Utermohlen continued to produce work up until 2000, and the two paintings here are amongst his best work. 1997’s Self-Portrait with Saw nods to the intrusive violence of cranial surgery (it was painted on the day he consented to donate his brain to science) whilst the portrait combines confusion, panic and a kind of slow-dawning horror at the loss of (self-) comprehension. The plastic-looking lower lip – like that of a ventriloquist’s dummy – suggests a loss of self-mastery.

Hanging alongside is another self portrait, this time from 1998, in which the brushstrokes are coarser, the result blurrier, bolder and more confused. A thick red daub divides head from body, as if to foreground a violent disconnect between body and head/mind. As the subject’s eyes lose focus, there’s a striking irony at work: with the brain’s decay accelerating, clarity is lost – of both sight and understanding – and yet this process is communicated, elucidated, through the means of the visual. Art most literally as mirror; reflecting back on its own insights with a fuzzy clarity of vision.

Affecting Perception is at the O3 Gallery, Oxford until 31st March 2013. The exhibition is supplemented by a programme of lectures and seminars.

axnscollective.org

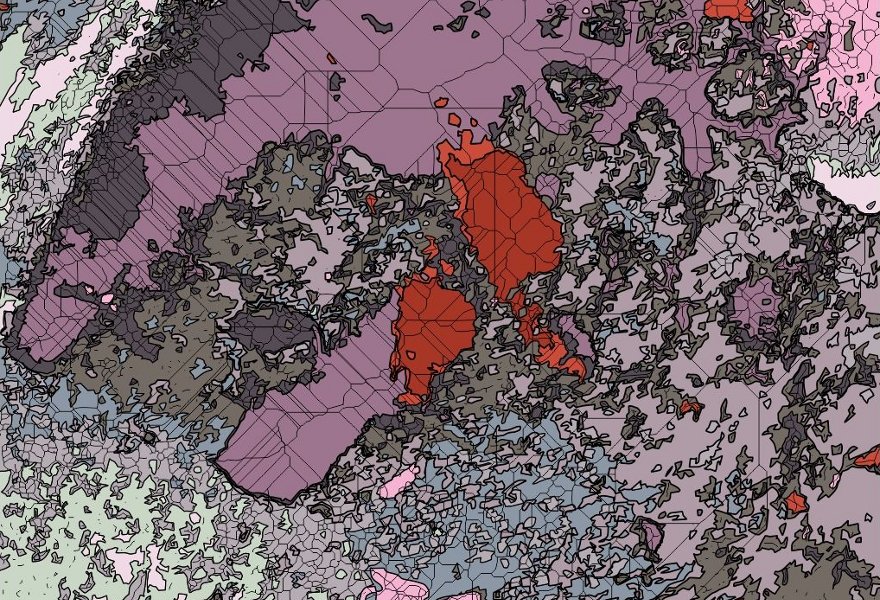

Image credit: Jon Adams, 228, digital manipulated photograph, 2012.

Add new comment