In 1840 George Catlin presented his Indian Gallery in Piccadilly’s purpose-built home of exotic wonderment, the Egyptian Hall. In the hyperbolic language of the day, the poster for the event boasted: “wild Feats of the Wildernesses of America...an occurrence that has not happened [in the civilised world] and probably will not again happen, in the lifetime of the Readers”. Nearly 175 years later, the original – and, it turns out, prescient – poster is on display at London’s National Portrait Gallery. It forms part of the first major exhibition of Catlin’s work in the UK since the artist, writer and showman accompanied his own Native American Indian Collection to the capital.

Understandably, the co-curators of George Catlin: American Indian Portraits have downplayed the more sensational aspects of Catlin’s early Victorian spectacle. Visitors should not expect to witness live performance rituals or war-whoops played out by native Ojibwas (or, as sometimes was the case, Caucasians). Yet, regardless of the missing live element, the exhibition – with its lovingly curated mix of Catlin’s paintings, manuscripts and indigenous artefacts – remains resolutely faithful to his pioneering spirit.

Far from an opportunistic showman, or, for that matter, a painter of unquestionable artistic merit, American Indian Portraits presents Catlin as a visionary, albeit complex, character. Catlin’s Indian Gallery was never quite lucrative enough to keep his head completely above water and in later life he found himself in a debtor’s prison. (Unsurprisingly, the US government of the time were not interested in buying his collection from him, but that did not stop him from propositioning them.) The poet Charles Baudelaire commended Catlin on his ability to capture the noble expression of the Native American peoples in a masterly way – but, tragically, this praise for his artistic endeavours was a rare exception. Still, as history has testified, both Baudelaire and Catlin were way ahead of their time.

It’s no big surprise that Catlin is attributed with envisioning the concept of the National Park.

Pennsylvanian-born Catlin has been criticised on counts of factual inaccuracy and exploitation (what else would you expect for someone who dressed their nephew, Theodore Burr, up as an American Indian for publicity stunts?), but he's still widely acknowledged as the creator of one of the most extensive and important records of indigenous peoples ever made. Forsaking a lifetime of stability and economic security as a lawyer, Catlin devoted himself to feverishly recording the cultures of the Native American peoples at a time of rapid change and conflict. Catlin’s work carries a sense of urgency, not, as some suggest, because of his lack of formal art training, but because he truly believed his subjects faced inevitable extinction. Under the brutal legislations of Andrew Jackson’s government, Catlin validly, if incorrectly, assumed that white encroachment and Indian removal rendered indigenous groups as vanishing races.

American Indian Portraits comprises just a fraction (less than ten per cent) of the Smithsonian’s collection of Catlin’s work, but by highlighting Catlin’s determination to capture the customs and ways of life, not just the likenesses, of indigenous people it effectively credits Catlin as being one the first known ethnographers. Considering his deep connection with America’s Great Plains and his predilection for preservation, it’s also no big surprise that Catlin is also attributed with envisioning the concept of the National Park – a good thirty years before the US government made his vision a reality.

The reappearance of Catlin’s work on British land is a timely one. Shockingly, considering the number of years which have elapsed, little seems to have actually changed in terms of our understanding of indigenous American groups or our dialogue with them. As one of the exhibition’s co-curators, Dr Stephanie Pratt, explains, she wanted the exhibition to draw attention to how Catlin’s work dominates representation of Plains Indians even today.

Hearing Pratt describe how her Native American ancestry relates her directly to the subject of a particular portrait on display (that of the Chief of the O-hah-kas-ka-toh-y-an-te Band, Big Eagle; tellingly, subjects never revealed their real names to Catlin believing that would be giving their power away) there’s a real sense of history repeating itself.

Pratt voices her own heartfelt belief that, despite not sharing the same language as her ancestors, she feels compelled to speak on their behalf. There’s so much we can learn from indigenous cultures, she implores, who start peace-keeping and healing ceremonies with the mantra “we are all related”. Then taking check of herself, she continues, only half-jokingly, “I suppose I’m a twenty-first century George Catlin – trying my hardest to make people listen.”

George Catlin: American Indian Portraits is at the National Portrait Gallery until June 23rd 2013.

www.npg.org.uk

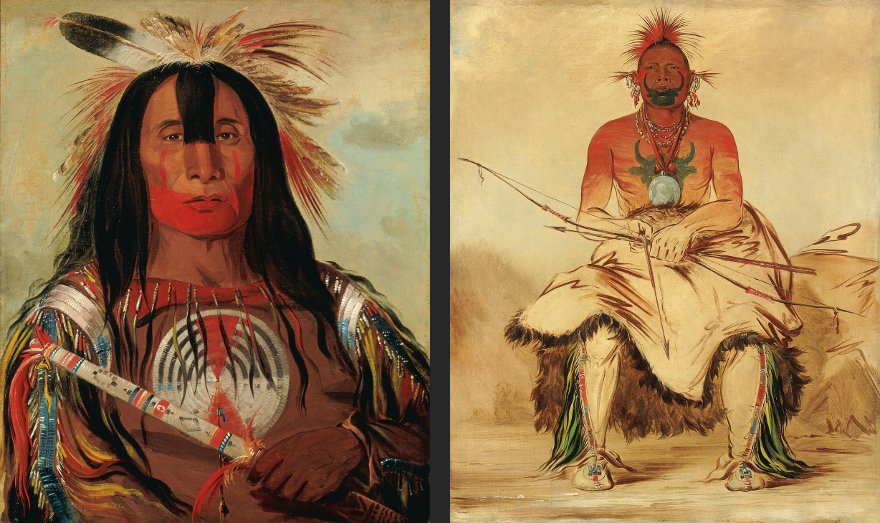

Image credits (left to right):

Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bulls Back Fat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe Blackfoot/Kainai, by George Catlin, 1832

La-dóo-ke-a, Buffalo Bull, a Grand Pawnee Warrior Pawnee, by George Catlin, 1832

Copyright: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Add new comment