Kaunas Correctional Facility. All photographs © Vaiva Katinaityte 2014.

KAUNAS, LITHUANIA — The pylons marching along Equipment Street — Technikos Gatvé, in the local language — are big enough to take the wide open spaces on the edge of town in their stride. The town in question is Kaunas, Lithuania's second city. Behind these pylons stretches a high brick wall. A sign by a discrete door says Kaunas Juvenile Remand Prison and Correction House. We were going inside, where spaces are tight. We were going to leave our identities with the guards, we were going to do time.

But not much time, not like the lads inside. We'd do just enough to see something that transforms not just a place but people, forever — a project called Made Corrections. David Ellis, an interventionist cultural agent with a track record of Lithuanian projects, called it “a world event — because it has opened all prisons for us”. This project started 1640 km away, in London, in a conversation between Ellis and Dean Stalham, an ex-convict turned evangelist for the rehabilitative power of art, and ‘guv'nor’ of an organisation that promotes what he preaches, Art Saves Lives. “All prisoners speak the same language” Stalham had always said. Ellis suggested testing that proposition in Lithuania.

“All prisoners speak the same language,” said Stalham. Ellis suggested testing that proposition.

Ellis used contacts, starting with the British Embassy, to get into the Lithuanian prison system. When he and Stalham were sitting with the Kaunas Facility director Markas Tokarevas, Stalham asked “how long have you been looking at those walls?” Markas replied “since Independence”. That's a long time — Lithuania re-emerged from Soviet occupation in 1991. “I want that wall” said Stalham.

Ellis negotiated with the Facility — they were on. So last year, Stalham met with Olly Walker, street art guru, author and head of creative agency Ollystudio, and they drew up a plan. Walker put it to JR, the French ex-guerilla artist known globally for his rolling Inside Out project, which uses blown-up black-and-white portraits of ordinary people, pasted up big in public spaces for maximum impact, and often with a political edge. JR had relocated to New York and had just finished a huge Times Square project. Nevertheless, Walker reports that the next day, “JR emailed back saying it was perfect”.

They found a local Lithuanian photographer, Donatas Stankevičius, whose hero is David Bailey. 200 inmates were gathered and asked if they wanted to take part. 39 stepped forward. Stankevičius photographed them the same day. “It's a project of trust” he'd say later, and he had just four shots to build it with each young man. They chose their own shot to be printed up and shipped by JR.

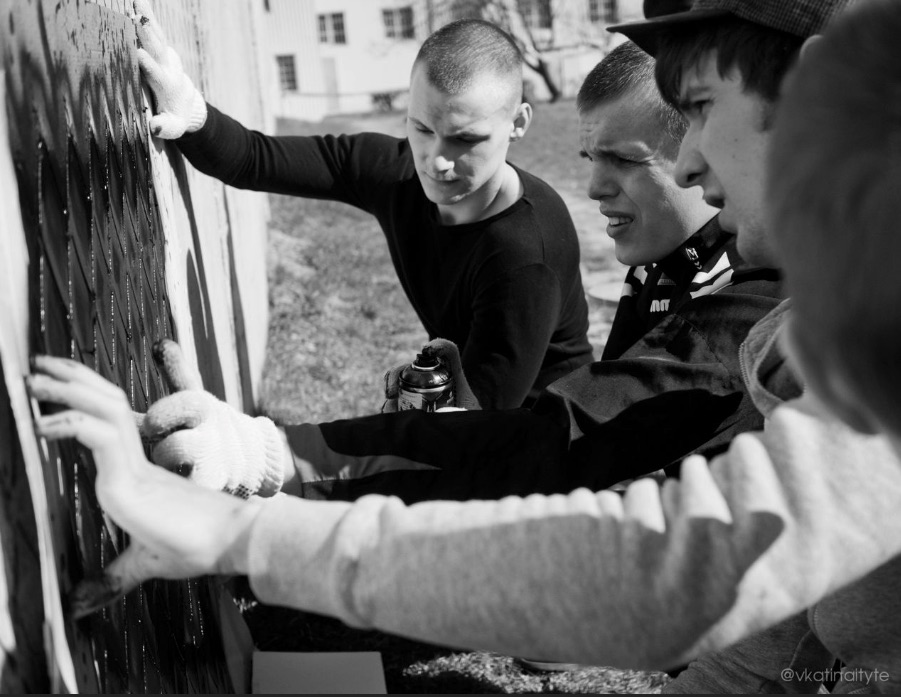

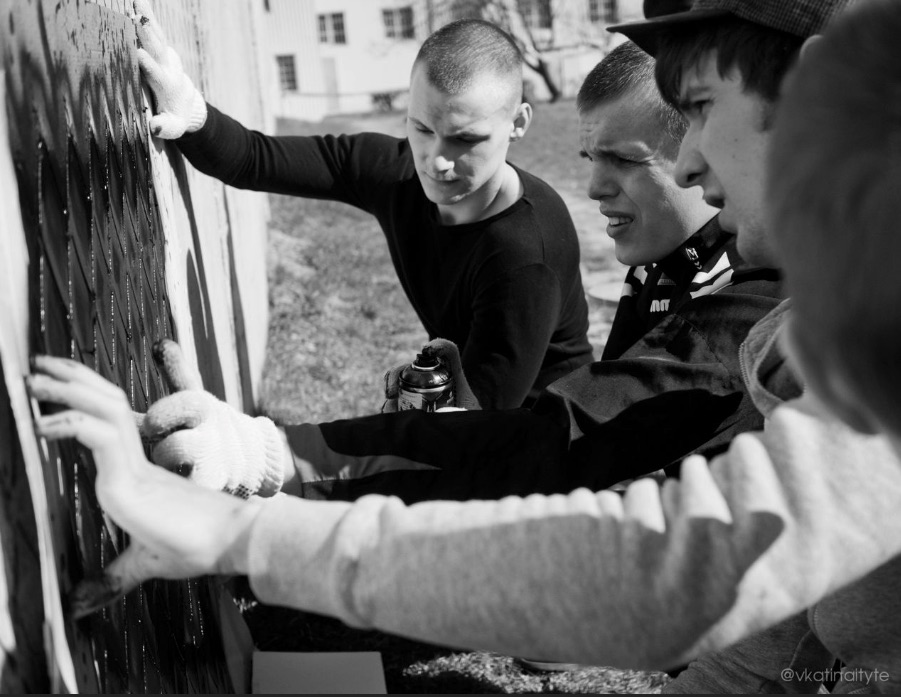

Soon after it was time for the Made Corrections crew, lads and facilitators, to do the job. They had the prints from JR, they had stencils from Walker, and another street artist was now in the mix, Ernest 'Zac' Zacharevic. He'd probably dismiss the compliment, but the wit and execution of Zac's international work is a match for Banksy. Photographer Vaiva Katinaityte was there to document as a part of the team. They had four walls in the Kaunas Correctional Facility. What Ellis had painstakingly knitted together was happening, and now he plunged himself into the operation.

There was another wall, too, in downtown Kaunas, facing the city's grand neo-Byzantine St Michael the Archangel church. On the evening before we'd all be in prison, Made Corrections were plastering those portraits up on an abandoned police station. With Walker up a ladder, Ellis fielding a media interview and Katinaityte snapping away, it took on an air of street theatre. That night, 39 faces that couldn't be there looked out on the city.

Oily Walker, left, and David Ellis . . . how to build a better wall.

The next day, the tenth, was the big one. Out at the Facility, the work would be revealed. We passed through the Facility's small door, handing over mobiles, passports etc before climbing upstairs into surprisingly light institutional corridors, painted lilac and yellow, and a big meeting room. The young offenders come marching, with a slightly swaggering step, all crew cuts, tracksuits and faces way more serious than their portraits. Some break step to stop and earnestly shake hands before we all sit for the speeches.

Outside, the exercise yard must have been a grim place. The concrete walls look like they might have once divided Berlin. A watchtower rises in a corner. But now, facing the main building, the wall smiles — with the 39 portraits, above another photographic strip, of happy eyes. On the side wall, stenciled fencing with body shapes is being cut by Zac's colourful painted characters. And nearby, in the wire net-ceilinged deep security isolation unit, its grim purpose belied by a basketball hoop, a bird of vibrant coloured triangles sits on a backdrop of white flowers. In an adjacent unit, more portraits, eyes and a scratchy face drawing. These spaces are alive!

All along the watchtower wall.

The Made Corrections crew didn't know what the boys were in for and they didn't ask. Those portraits gave them an identity beyond their past. The work made them trust strangers again, and themselves. Perhaps the strangest thing is how when 39 volunteered to take part, 161 did not. Why? Ellis reckons it was fear.

Ellis will be back in May continuing his engagement with the inmates through drama and improvisation workshops. Walker plans to return too. Stalham's idea that art saves lives won't be leaving any time soon. But the lads in the Facility will leave. Hopefully, they made corrections.

In his speech, Ellis looked at those in the crew straight on. “No offence”, he said, “but don't come back”. ≈ç

A job well done, and promise of more ways of seeing themselves — now and later.

HERBERT WRIGHT is a London-based author and journalist specialising in architecture and art, and contributing editor of The Journal of Wild Culture. He studied Physics and Astrophysics at the University of London. He is currently a contributing editor of Blueprint magazine, columnist on the Royal Institute of British Architects Journal, and contributor to le Courier de l'Architecte.

This article first appeared in The Journal of Wild Culture on April 27, 2014.

Add new comment