View from Roden Crater’s crest. Photo by Luciano Zoratti.

Any landscape is composed not only of what lies before our eyes, but what lies in our heads.

— Donald W. Meinig, cultural geographer

As you drive south from the Cameron trading post, toward Flagstaff, Arizona and the southwestern rim of the Colorado Plateau, cinder and jagged basalt oust the Painted Desert’s sinuous shale. The blond grasslands appear torched, hardened with lava veins, blackened with pustules and scabs like charred skin. While this sector of the North American tectonic plate was sliding across a hotspot in the planet’s mantle, molten rock pushed through fissures and cracks, oozing from the surface, or, mixed with gases, lobbing fiery mayhem mile-high. With the crust steadily inching northeastward, volcanoes boiled up, geysered, and fizzled, and the San Francisco Volcanic Field stretched taffy-like into a fifty-mile belt of more than six hundred vents.

Near the apex of Highway 89, Sunset Crater marks this ground’s most recent violent birthing, which occurred during the late fall or winter of CE 1064-1065. (Archaeologists determined the date by analyzing growth rings of wooden roof beams buried under volcanic debris.) Terrified, the local Sinagua abandoned the cornfields they had farmed for generations. Ancestral Hopi, who witnessed the flare-up and attendant mushroom cloud from their distant mesas, consigned the spectacle to collective memory. Their myths recall a vengeful katsina — a genius loci with a flame-colored, tube-snout head — that ignited a mountaintop because sorcerers wronged him. Out of control, the blaze quickly merged with the underground hearth of Maasawu, god of fire and death; a red gash split the earth like an overripe melon, raining end times upon people.

This pool will immerse you in the pulsing, birthing, unbounded universe.

Although the plate continues to drift, the once volatile field now lies dormant, monitored by geologists armed with seismographs. In 1928, Sunset Crater was designated a national monument — when a Hollywood movie company wanted to blow it to pieces to simulate a landslide for a Zane Grey adaptation — but most neighboring cones still lack protection. Off-road vehicles razorblade some; earthmovers gut others for landscaping and building material and to grit icy roads. In a strange plot twist, one defunct crater has become the obsession of a man who is turning it into monumental art — capturing light from the sun, moon, and stars, showcasing Earth’s envelope of air.

At an elevation of about five thousand feet, Roden Crater balks on a bunchgrass-and-brush plain as if cut from its herd, one of the easternmost cones in the volcanic field. Several eruptions assembled this rather young crater, the last almost 500,000 years ago. A black basalt dam girdles part of the base below the brick-red crown. In aerial shots, a secondary vent or “fumarole” looks like offspring, a smaller growth in the crater’s flank. The main volcano’s low, weathered profile is nearly symmetrical and certainly sensual; James Turrell, the artist and owner, has compared Roden Crater to Man Ray’s celebrated canvas of scarlet lips in the sky. Kissed by sun, it blushes at dawn. It whitens with snow, darkens beneath curtains of rain that may or may not wet the ground, and once in a while, anchors a rainbow’s ghost arches. On some days, Maynard Dixon-clouds race their shadows across the desert backdrop. The view from the rim opens the world like a fisheye lens. To the south and west, above cinder hills and pine forests, the San Francisco Peaks tilt skyward, their crest unabashedly naked. Navajo Mountain bulges faint and blue on the northern horizon, more dream than reality. Due east, beyond the Little Colorado’s seasonal Grand Falls, sprawls the bulk of the Navajo reservation.

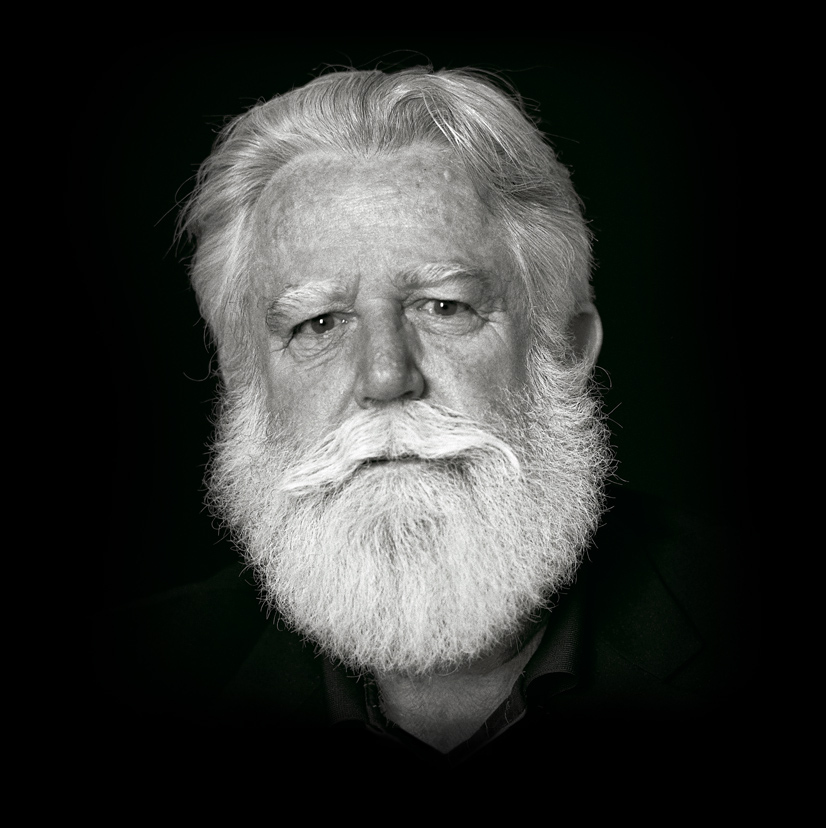

Trying to describe the 72 year-old Turrell — a large-framed, fitter Santa; a druid in cowboy duds — the term 'Renaissance man' comes to mind; his biography is as colorful and inspiring as his art . . . and its setting.

Aerial view of Sunset Crater. Courtesy of National Park Service.

James Turrell grew up in Pasadena, where his Quaker grandmother encouraged him to sit quietly and “greet the light inside.” As an independent child with scientific leanings, the physical qualities of light fascinated him early on. He once pricked holes into an old World War II blackout curtain in his room that, when daylight fell through them, shone like constellations. A man-moth drawn toward Earth’s largest natural light source — wildfires, magma, and bioluminescence are negligible, non-celestial — Turrell, who by now has logged more than seven years in the air, got his student-pilot license at age sixteen. In college he majored in math and perceptual psychology and mixed his curriculum with healthy doses of art and art history—all interests he would pursue throughout his life.

During the 1960s, the hippie conscientious objector supported himself as a car mechanic, airmail carrier, crop duster, and pilot for an aerial burial society, before starting a company that specializes on rebuilding antique airplanes. Turrell counseled young men who tried to avoid the Vietnam War, was convicted, and spent time in solitary confinement. He also collaborated with a physiological psychologist, experimenting with sensory deprivation chambers. Both experiences may have influenced his spare, architectural style and reinforced his choice of subject matter. Turrell became loosely affiliated with California’s light-and-space artists. Though widely accepted and commissioned to create pieces, he scorned the art world’s commercial aspects to the point where he returned an advance, because he did not like selling his work after he’d finished it. He leased a ramshackle hotel in Los Angeles as a studio, and when he cut an opening into its roof for his first interior “skyspace,” his landlord made him repair the damage.

When developers bought the city block with his studio in the early ‘70s, Turrell decided to take his art into nature. The search for the perfect site had begun.

The visual arts were about to return to the San Francisco Volcanic Field, this time to build, not to destroy.

Turrell devoted seven months and close to seven hundred hours of flight time to combing the western United States from the Rockies to the Pacific, from the Canadian to the Mexican border. At night he rolled out his bag and went to sleep canopied by the wing of his Helio Courier plane. As an artist and seasoned pilot, Turrell was sensitive to ground as well as bird’s eye-perspectives while scouting for a project site. His grand design called for a privately owned place of power that interacted with the sky and the rarefied western air. In his mind he pictured a cone, truncated, roughly shaped like a satellite dish and thus conducive to a phenomenon known as “celestial vaulting,” a sky bowl-effect more pronounced when the viewer’s position is far above the ground. In 1974, at long last, he found Roden Crater. Far from any light or air pollution, it seemed perfect — and familiar. As a child, Turrell had once camped with his parents at nearby Sunset Crater. In one of history’s quirky loops, the visual arts were about to return to the San Francisco Volcanic Field, this time to build, not to destroy.

After negotiating for three years with a crotchety landowner who was not really in the market, Turrell bought the Walking Cane Ranch, which came with grazing leases and the crater, 156 square miles altogether. He turned cattle rancher by default, to qualify for a bank loan, and ranching still subsidizes his art. The loan was not enough to cover the project’s gargantuan cost — ballooning to twenty million dollars — but, fortunately, some private foundations supported Turrell’s vision. He still went nearly broke several times.

In the tradition of visual artists like Ansel Adams, Turrell built and lived in a log cabin near the crater for nineteen months, studying the play of light on the cone throughout the year before setting to work. His blueprints outline nine underground chambers, four aboveground (oriented to the cardinal directions), one large outdoors space (the volcano’s throat), and walkways and tunnels connecting these focal points.

Crater’s Eye. Photo by Luciano Zoratti.

Turrell began crafting his celestial theater in the late ‘70s and, more than thirty years later, is still at it. But seating remains rather limited. With the exception of a few journalists and potential donors, no visitors are admitted until the project’s completion, which has been delayed repeatedly. Some critics say that, like Antonio Gaudí’s cathedral, Sagrada Familia, it will not be finished in the artist’s lifetime.

The numbers may be impressive, but by themselves do not do justice to the culmination of a life’s work: the architectural equivalent of the Great American Novel. Turrell’s brainchild makes Walter De Maria’s 'The Lightning Field' (in New Mexico), Robert Smithson’s 'Spiral Jetty' (in Utah), and even Michael Heizer’s 'Double Negative' (in Nevada) look like mere short stories. Influenced by megalithic sites in Ireland, Iron Age hill forts in England, Egyptian temples, and Southwestern archaeo-astronomy, Turrell sees Roden Crater as a shrine that transcends the ages, a naked-eye observatory that could outlast our society.

By translating exterior into interior space, Turrell seeks to connect observers with celestial rhythms and “old time,” the millions of years it takes light to arrive here from distant galaxies. He oversees the sculpting of light by which the crater becomes both object and atmosphere. In Turrell’s creed, “it’s what’s behind the eye that forms the reality we create.” The presentation of stimuli in new and unusual contexts shakes us from the stupor of dulled perception, like the “blue” of fair-weather skies that we take for granted and whose nuances we seldom notice. Working with projected and ambient light, Turrell explores variations in color, density, brightness, and mood, and how these affect our sense of space. Time of day, season, and atmospheric conditions all matter. Even the terrain outside the crater adds grace notes to the light’s symphony. True to his training as a perceptual psychologist, Turrell does not ignore the non-visual either—his approach is multi-sensory as well as multidimensional.

Where to start a tour of hallways that house the cosmos?

The Sun and Moon Space, one of the chambers already completed, could be the most impressive feature. It functions like a pinhole camera. A thirteen by fifteen-and-a-half-foot marble slab, the largest single piece ever quarried in the United States, stands at its center; a keyhole-shaped tunnel slopes upward from the chamber for almost nine hundred feet. Facing southwest, this gallery channels light downward during the moon’s southernmost apogee. A second tunnel, oriented toward the northeast, will direct light from the perfectly aligned rising sun on solstices. That sun will touch the central monolith. Once every 18.61 years, when the full moon pauses at its lowest in the southern sky, it will project an eight-foot-wide lunar image on the monolith’s backside, an image so clearly defined that details of the moon’s face will be visible.

Like a Greek amphitheater (where stage whispers are audible in the topmost seating tiers), the east tunnel has been calibrated with sound effects in mind, sensitizing art connoisseurs to often-ignored acoustic space. From the tunnel’s halfway point, a person’s voice carries to the Sun and Moon Space, or, when facing in the opposite direction, to an upper chamber, the East Portal.

East Tunnel. Photo by Luciano Zoratti.

At the head of the east tunnel, a skylight has been cut in the ceiling of a large elliptical room. This East Portal — a skyspace like Turrell’s early, modified LA studio — endows natural light with a sculptural presence. “The sky is no longer out there,” states Turrell. “It’s brought down into our territory.” Sandstone benches line the walls underneath this opening, where visitors to the cosmic kiva can sit and contemplate the almost tangible panel as it changes from robin egg-blue to diamond-dusted black velvet. A recessed ellipse in the room’s floor will hold white sand, which, saturated by rainwater, reflects starlight. According to Turrell, the glow of Venus alone will be enough to see your shadow by. A second aperture will frame Polaris—or whichever star marks the celestial pole in a future that may or may not contain us. This oculus will keep the star centered while the observatory apparently rotates on it like a wheel on an axle. This, of course, defies our expectation of stars arcing across the firmament, but, because only planets wander (all stars are “fixed”), is exactly what happens.

At the East Space, the migrating sun will glance off an “infinity pool” whose mirror surface extends the horizon. Its rays will illuminate the room, which on windy days will shimmer with gossamer nets of gold cast by the water’s ripples.

The South Space will receive light from the sun at its zenith. At night, it will allow astronomical sightings aided by stainless steel maps set into the black floor. This “chart room” will also serve to predict eclipses in the Earth and moon’s minuet around the sun.

Lastly, the music of the spheres will caress you in a light-catching cistern near the fumarole’s crest. Light sucked into a quartz ring around a pool will be redirected to lid the water with a radiant layer. A parabolic dish under the pool will pick up electromagnetic waves from quasars and other heavenly bodies and transmit them into the water where visitors floating as if in amniotic fluid can hear and feel them. Unlike any solipsistic deprivation tank, this pool will immerse you in the pulsing, birthing, unbounded universe.

Facilitating a different, open-air sensation, a steep flight of bronze stairs ascends from the floor of the East Portal to its elliptical eye. The luminescent path leads outside, to the crater’s light-flooded arena, suggesting rites of passage, rebirth, spiritual awakening.

Bulldozers have moved more than a million cubic yards of earth and rocks, landscaping the rim of the cone into an elegant, even-leveled oval, an almost-perfect parabola. Four tilted limestone platforms arranged like compass points at the bowl’s center invite viewers to lie on their backs and, engulfed by humming silence, lose themselves in a dome made of sky. Here, they can slip off Earth’s tethers, questioning their position relative to the thing observed, as they did at the pole star-fixing portal. Am I looking up or down? Am I going to fall or levitate into space? You could be probing the sky or fathoming a Caribbean sea. This optical illusion confounds sky watchers wherever horizons are unobstructed, but elevation and framing intensify it. The effect of this delicious vertigo has been known for centuries, and painters like Michelangelo have used it on cupola ceilings to make frescoes “pop.”

The view from the crater’s rim conjures up a similar sleight of eye. On clear, sunny days the landscape appears to curve toward the sky, in a kind of reverse vaulting. “We actually give the sky its color as well as its shape,” Turrell has said in an interview. Like a trickster-demiurge Turrell changes both, by changing the context of vision. One can only wonder what other aces this modern da Vinci has up his snap-buttoned sleeves.

To preserve his artwork’s integrity and that of its setting, Turrell has vowed to protect Roden Crater’s “viewshed.” Among other things, this involves sustainable ranching. The land that he leases and owns and on which he runs cattle acts as a buffer around the crater, preventing any form of development. In 1997, he also persuaded Coconino County authorities to pass a “dark sky ordinance,” which eliminates unwanted brightness from upward-directed commercial and domestic lights within a thirty-five mile radius of his site. The Coconino County seat, Flagstaff — the only sizable town close by — has long embraced skies suited for stargazing. Half a dozen major telescopes ring the city, including the one from which Pluto was discovered. (It has since been demoted from planet to dwarf planet.) In 1958, Flagstaff implemented lighting restrictions, which are thought to have been the world’s first. The city and county passed more lighting ordinances in the ‘80s, and today’s dark sky-activists continue to educate local residents about ways to preserve the night and its wonders.

James Turrell. Photo by Florian Holzherr.

As a desert dweller, land artist, and quite a recluse, Turrell not only tunes in to the natural environment, but also to the quality of the visitor’s experience. When the observatory finally opens to the public, only fourteen people per day will be allowed inside and even fewer, to stay overnight. One day per week will be reserved for schoolchildren only. Unsure if demand will surpass the observatory’s carrying capacity, Turrell considers granting access by way of a lottery — winners can thank their lucky stars while beholding them through Roden Crater’s apertures. The best viewing hours generally fall between pre-dawn and a little after sunrise, and between sunset and midnight. Ever the perfect host, Turrell therefore drafted a little guest lodge, partly concealed in the crater’s side. He even designed its furniture. The slopes will eventually be replanted with native wildflowers and grasses and any areas disturbed during construction restored for wildlife. Passersby will hardly notice a difference in the crater after all work has been completed.

Fittingly, harmony was also restored after the wrath of Sunset Crater’s katsina had run its course. As in any good yarn, the bad guys met a bad end. All evildoers suffocated or burned to a crisp. Maasawu, the Hopi Lord of Death — and Creator — settled down again in his underground realm.

Looking at country scarred by divine temper or searing tectonic upheaval, it becomes easy to accept destruction as creation’s indispensable twin. What nature raises with one hand it rubs out with the other. Between cataclysms, briefly, our kind is allowed to thrive. If in some unforeseeable future the San Francisco Volcanic Field awakens again, the fire below will greet the light from above in another display of terrible beauty. Until then, Roden Crater rivets our awe and attention on this sun-blasted plain.

MICHAEL ENGELHARD is the author of the forthcoming essay collections American Wild: Explorations from the Grand Canyon to the Arctic Ocean, and Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon. As a wilderness guide in the Grand Canyon and Alaska’s Arctic, the only natural disasters he ever witnessed were flash floods in canyon country and avalanches and forest fires in 'up north'.

View the author's site.

Purchase his books: American Wild and Ice Bear.

Add new comment