X-ray image of bound feet.*

LONDON — You may have heard about how, long ago, it was a Chinese feudal tradition to tightly bind girls' feet, crushing their bones and leaving them deformed for the rest of their lives. Some are still alive today, and Hong Kong anthropologist and photographer Jo Farrell has spent a decade tracking them down. These are survivors, women who lived through the Great Chinese Famine's 'Three Bitter Years' from 1958-1961, and are now in their 80s, 90s and beyond. She presents 50 in her new book, Living History: Bound Feet Women of China.

"I wanted to look beyond the feet," says Jo. "I wanted to celebrate and be sensitive to these women".

When she first started thinking about women who had had their feet bound none of her contacts knew of any. Foot binding was banned in 1912 but persisted until Mao Zedong declared the People's Republic in 1949. Some denied that there were any to find any more. Jo comments that "these women became invisible".

She was known as the most beautiful woman in the village.

Her break came when a Shanghai taxi-driver overheard her talking about it and offered that his grandmother was a bound feet woman. Six months later, in 2006, Jo met her, a lady born in 1927 called Zhan Yun Ying. The welcome was warm and within an hour she agreed to have her feet photographed. She let Jo touch them. "It was like holding an artform", she recalls. "They were so soft!"

Jo explains that the purpose of foot binding was "to honour and obey your father, husband and son... If a woman had had her feet bound, she would be subservient and a good wife". No man apart from her husband would see the feet. They were an intimate thing of beauty, forbidden fruit. Foot binding was a passport to marriage.

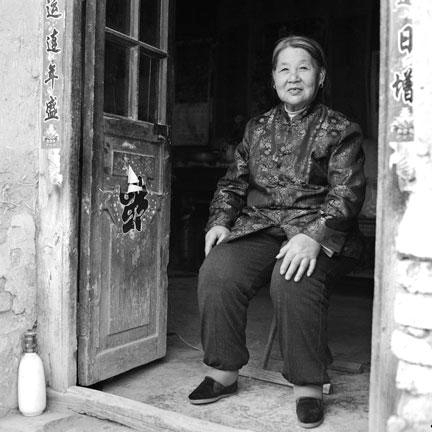

Su Xi Rong in her doorway, and her shoes.

Matchmakers would arrange weddings, sometimes for sons that hadn't even been born. The bride would be carried by sedan chair several kilometres to the wedding, followed by chests of gifts from bedding to kitchenware for the new home. Without foot-binding, there was no guarantee of a husband. "They would have a horrible life", says Jo.

It was done to girls from 3 to 15 years old, and some bound their own feet. Toes scrunched up beneath the foot. Young girls were commanded to walk, to break the bones, and the pain was excruciating. Walking in deep winter was some relief, because the feet would be numb. But unbinding the feet was painful too.

She is proud of her feet and what she's achieved.

Foot-binding is often associated with the elite, but all of Jo's subjects were rural — workers of the land. Her journeys took her far from the futuristic megacities and deep into the provinces of Shandong, Yunnan and Guangxi.

Take the example of Su Xi Rong. Jo found her in a village two hour's drive from Jinan, Shandong, in 2007. She was the grandmother of one of Jo's translators. Born in 1933, she is almost a spring chicken amongst Jo's women (another lady near Jinan was 103 in 2014). Su Xi Rong’s feet were bound as late as 1940. She was known as the most beautiful woman in the village, because of her feet. She told Jo how, when she tried to unbind her feet, her mother would cut small slivers from her toes as punishment.

A foot of Su Xi Rong. "It was like holding an artform".

Her two daughters and her son are now in their sixties and retired. But Su Xi Rong was still working when Jo found her in 2007, taking husks off corn from the fields. Her husband died in 2008 (and it was the men who received the state pension, not the women). Jo caught up with her again last year, in 2014, and Su Xi Rong plied her with pork and chive dumplings. They probably explain why she had put on weight — now, she gets driven around in a sort of electric wheelbarrow. She feels no bitterness. "She is proud of her feet and what she's achieved", says Jo.

There is a sense of loss in the countryside as people have left for the cities. Since Deng Xiaoping's reforms, it's been the largest human migration in history — a fifth of China was urban in 1980, now it is more than half. The old are left in another world. Pictures of Mao and Deng hang on walls of houses that are otherwise little changed from those of centuries ago. Nowadays, the cities are catching up with some villages, swallowing them up as they expand, and some of the survivors of foot-binding have moved into China's endless urban high-rise housing. Occasionally you can even spot them in the city crowds by the way they walk. But in modern China, says Jo, foot-binding is "a tradition they want to pretend didn't happen".

Jo can see the parallels between foot-binding and practices like FGM (female genital mutilation) elsewhere. However cruel and abhorrent, she understands why outsiders' prying can cause resentment and why even victims may respect the traditions. But history should not forget. Thanks to Jo Farrell the stories of Su Xi Rong, Zhang Yun Ying and countless other Chinese bound feet women will not be forgotten. They are stories of pain, but also pride, joy and survival.

Jo Farrell with Jiang Hua Ying, her family, and a taxi driver, in 2014.

Jo Farrell's book Living History: Bound Feet Women of China can be purchased here.

Satire on the extreme corseting of society women: European traditions, too, have abused the female body. Image credit.*

This article's first appearance was in The Journal of Wild Culture, June 26, 2015.

HERBERT WRIGHT is a London-based author and journalist specializing in architecture and art, and an editor of The Journal of Wild Culture. He studied physics and astrophysics at the University of London. He is currently a contributing editor of Blueprint magazine, and contributor-at-large to Design Curial. www.herbertwright.co.uk

Photos from the book: Jo Farrell ©2015.

Add new comment