VIP observers watching the explosion of an atomic bomb in Operation Greenhouse on Enewetak Atoll, 1951. [o]

"I have an idea!" Manuel laughed a raspy, staccato laugh. Then reaching out to me with his sad, round eyes, he popped the question. "Why don't you marry me?"

The bones in my body recoiled. I'm a research psychologist, and Manuel was my interviewee. There was a way about him, for sure. But I'd only known him for a few minutes.

"Hey, I'm kidding." He caught my discomfort. "No woman ever wanted to marry me . . . you know . . . not since 1951."

Before this day in 1985, I had never met a man who had seen the raw force of an atomic blast. Now I had. He was Manuel Cordero, former U.S. Marine, former soft drink driver, now surviving, or I should say barely surviving, on his mother's welfare check.

Manuel insisted we meet at the research center, not at his mother's house in the valley. When he arrived, he was wearing a blue plaid flannel shirt and jeans. It looked to me like he'd just taken the shirt off the cardboard and put it on his back. He was a stocky man, over fifty, with a black moustache set in the center of an etched brown face. He walked into the conference room, limping slightly, and a foot behind him hovered the quiet outline of Felipe. I wasn't supposed to do the interviews in the presence of a third person. An awkwardness took hold of every molecule in the room, yet looking more closely, I detected that Manuel and Felipe were inseparable.

Once when I went to the V.A., the doctor took me into the hall. He said he thought my conditions came from radiation, but he couldn't write that down.

"Can Felipe stay with us?" Manuel asked.

Thinking quickly, I reached out to shake Felipe's hand. He was slight, shorter and thinner than me, and he responded to my gesture shyly. Manuel explained that Felipe had also been injured in the service, but not by radiation.

The two of them were bonded together, he said, by the missions they made to the Veteran's Association for health care that never materialized. They were also bonded by the fact that Felipe brought Manuel water at night and held his shoulders down when he writhed on the sheets in pain.

"Yes, please, Felipe," I said. Please. Come in."

I pulled my tape recorder out of the briefcase and set it on the table while Manuel signed a form assuring me I could use the interview for the book I was writing. He would be the twenty-third person I had spoken with, each one in deteriorating health from contact with some dangerous technology. There had been, before him, Jane Glendon, a housewife from Love Canal. There had been Catherine Wallace, a Long Island Dalkon Shield survivor, George "Gung Ho" Smithson, Agent Orange veteran from Las Cruces, and Danny Toms, exposed to pesticide drift in Texas. Now there was Manuel Cordero, atomic veteran.

We sat down, facing each other, at one end of the long conference table. Felipe silently seated himself a few chairs down the side. We began to talk. Manuel apologized for being the kind of person who would talk on and on. He spoke with the melodic lilt of Spanish translated into English.

These moments before the interview were, as always, like stuck ice. Just before melting into the connection, my interviewee and I would feel strange, adrift, as if departed from the normal world where technology-induced illnesses were not spoken of, but not yet arrived in a place where they could surge forth. Luckily, I had stock questions I asked at the beginning of each encounter. "What technology do you think caused your illness? Tell me how your exposure contributed to your health problems."

The innocent 1950s . . . not much going on a lazy Las Vegas afternoon. [o]

I felt stiff, but Manuel plunged right in. He told me how he had gone into the Marines, the only man in boot camp who did not speak English. He told me how everyone back in the barrio had seen him as a hero and how hard he had pushed to fulfill their vision. He told me about the maladies that had beset his body since seeing the blast in 1951.

"I got lesions," he said, rolling back his shirt sleeve and pointing to scars on the skin. "Lesions as big as silver dollars, and the doctors at the V.A. always say they don't know what they are. Then I gain weight for no good reason. I only eat once a day, just beans and tortillas and chili once a day." I had heard these symptoms before.

"I was engaged to be married to this girl," he explained, "but then I found out I got sterile and she left. Then I was hauling Coca-Cola and Pepsi, my bones began to ache so bad I couldn't pick up a case of bottles. I had to quit, and I haven't worked since."

The details of each person's life were always unique. I sighed. The stories were all the same.

"I got bouts of pain," he went on, "usually in the night. Then last year I went blind in this one eye. They gave me a prescription for glasses but I don't have the money . . . and you know what? Once when I went to the V.A., the doctor took me into the hall. He said he thought my conditions came from radiation, but he couldn't write that down. So they don't give me much medical care."

I'd heard this before. Inside my mind, an assemblage of psychology professors instructed me to make note of the common theme. I wondered. They would not be so pleased if they knew that my blood was boiling in rage.

Then Manuel told me about the blast. It took place in Yucca Flats, Nevada. There along with thousands of other teenage boys dressed in combat fatigues, Manuel was trucked into the barren landscape and told to wait in a foxhole. Then they set off the bomb.

I could see by the relief he felt after telling me the story that while this moment had laid the ground for all the anguish and lost opportunities of his life, it had also lain like a bird with no throat. Now he was bubbling over in song plaintive, quivering, hopeful song. Here was I, leaning toward his face, nodding my head, thirsty to hear what every other person, from the doctor at the V.A. to the waitress at the corner restaurant, did not want to hear.

Test participants do the town. [o]

Just then the recorder clicked off. Our bodies jerked from the sound. Manuel pushed his chair back to regain balance, and its legs screeched against the wooden floor. I turned the cassette over, nervously moved the microphone an inch closer to Manuel, and asked another question. "What did you learn from this experience?"

He sat for a moment staring into the air and then shook his head. "No. I can't say."

I switched to something more concrete. "How far from it were you?"

He leaned toward the window at the end of the table and squinted across a field of fenced backyards and one-story adobe houses.

"Uh . . . you can't really see from here, maybe to University or Girard."

"A mile?"

"Oh yes. A mile. More." A stillness lodged in the room, punctuated by Manuel's lungs softly wheezing in and out, in and out. I was beginning to feel at ease with him and with his friend Felipe who sat so quietly with us at the table.

Then, resolve lifting Manuel's ribcage and turning it back from the window, he faced me eye to eye.

"There is something else that will be with me forever," he announced. "The blast, it was awesome. I had never seen anything so destructive, but this other thing, it is totally different because it is something inside you that you can't cope with."

He shifted his hips from side to side, and the chair creaked as he set them down.

"My mother always told me you don't pray for yourself," he said. "You pray when you know someone is sick and hurting and you want them to get better. Or for someone who is in trouble. But you don't pray for yourself. So when I pray for other people, I see them. When I was in Korea, I saw the babies running around lost. We couldn't stop. We were marching through a village and getting rid of the enemy. But the children, their houses were blown up. God knows where their parents were, and they're running around scared and lost and naked . . ."

I'd have been court-martialed and gone through whatever trial and punishment they had. If I had to come out of the service with a bad discharge, then I'd have come out healthy . . .

Manuel dropped his head and stopped breathing. "I can't anymore."

"Speak?" I asked. " . . . yuh."

He could just barely get the word out. I turned off the recorder, and Manuel sat slumped over for a long minute. I felt uneasy. I looked to Felipe. His eyes, his heart, every cell in his body were focused on Manuel, and he was breathing with a slight exaggeration, as if to encourage his friend to stay alive. Then, without signal, Manuel started again.

"Their bellies." he said, "they were big and round, but you know, they were starving to death. We had to keep walking fast, and what I would do is I would take a can of beans out of my pack and open it and drop it on the ground for them." Manuel was speaking fast now, almost panting.

"There was this one little girl," he said. "She had a great big belly, but her arms and legs were like sticks. I handed her a can. Then all the other kids surrounded her like vultures. They grabbed it away, and she was screaming. She ran after me and clung to my leg as I marched . . . and I had to keep marching . . ."

By now my skin was prickling and my eyes brimming with hot tears. "Oh God!" I wanted to call out. "Why?!" An urge rose up through my chest, an urge as strong as a flood tide, and it streamed down my arms. I wanted to protect this man. I awkwardly groped for his hand. I couldn't find it. Then I lurched forward to him, and as I did, I sent the tape recorder flying across the table into a tangle of plastic and wire.

Everything stopped. I am sure all three of us stopped breathing. Then, slowly, unmistakably, the silence was infused with embarrassment. The tape recorder had landed in front of Felipe, and he began, meticulously, to reassemble it into some order.

"What was that you asked before?" Manuel interjected, his words chafing against a raw throat. "What did I learn from all this? I learned, yeah, I learned that war is stupid. It just . . . doesn't . . . make . . . any . . . sense. And if I'd known about that radiation, I wouldn't have gotten into that trench. I'd have been court-martialed and gone through whatever trial and punishment they had. If I had to come out of the service with a bad discharge, then I'd have come out healthy . . . and I'd have been a father."

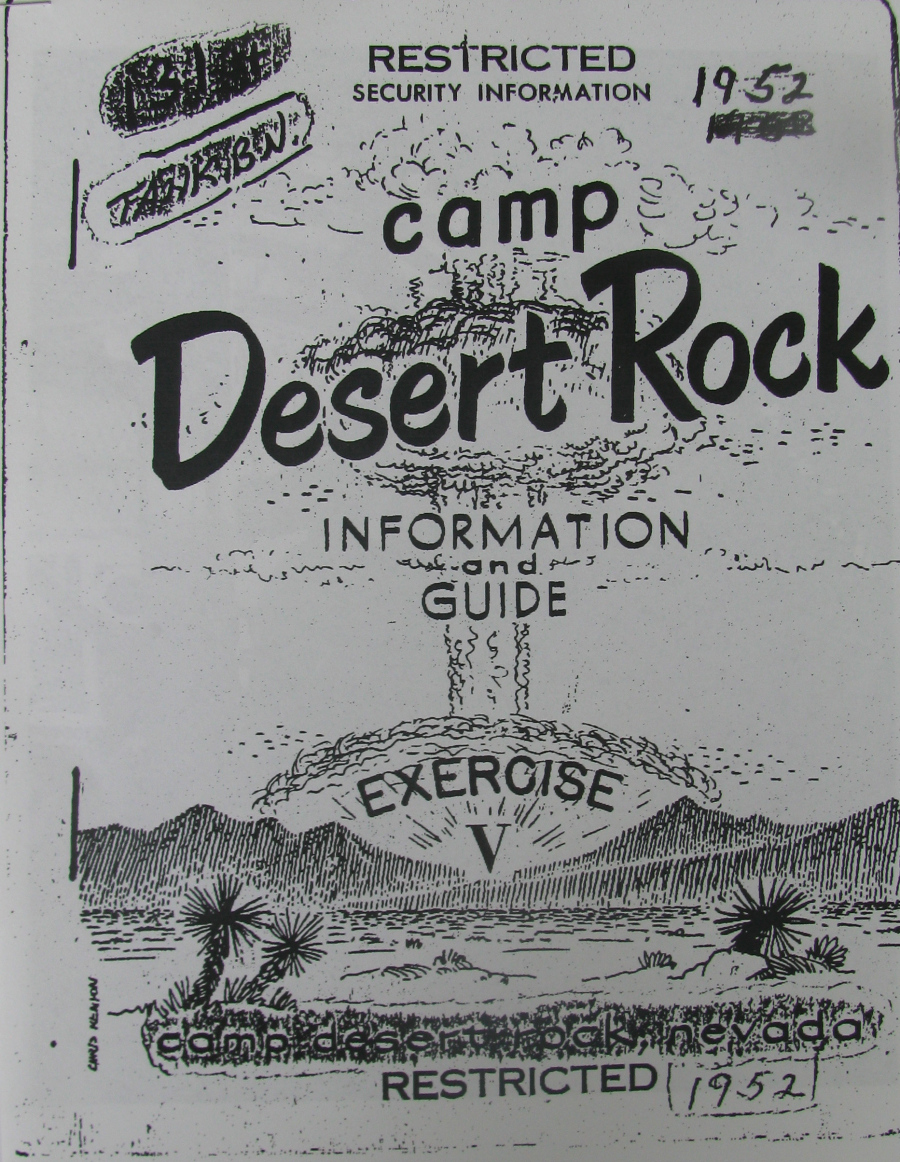

Exercise V . . . manuals did their best to prepare participants for the experience. [o]

Without a sound, Felipe stood up and floated to Manuel's side. He placed his hands lightly on his friend's back.

"I wanted a family so bad!" Manuel cried out. "You don't know how much I wanted a family.

The last vestiges of my role as detached professional dissolved. Sure, I had brought more compassion to the job than most researchers. I had felt my interviewees' pain. I had tried to get them free health care and encouraged them to join survivors' organizations, but always afterward, always when my actions would not influence the interview. But now I no longer cared about the rules. "When I stood up," Manuel told me, "I saw the mushroom, the bright red streamers of fire flying down from it, a donut of fire billowing out in all directions."

"I completely forgot to tie my helmet and put my gas mask on. I didn't know what was happening," he said.

"The helmet blew off. I completely forgot everything. I was just looking at that cloud. Then the blast came. It roared louder than anything you ever heard, and it threw me against the hole!"

The roar that threw him against that hole still reverberated. Every breath he now took was overshadowed by that moment in 1951. Every day was a challenge greater than any Marine hero could know, and every day Manuel faced that challenge. I could see this. Felipe could see this. Now the two of them sat side by side, Felipe's arm draped over Manuel's shoulder, Manuel wrenched in quiet pain.

In my own body, I felt not just the sense of futurelessness that had vibrated in me for the duration of the Nuclear Age. I felt the full roar of the bomb. What could I possibly do to offer this man some sustenance? He needed the life he had been denied. He needed to know that despite the Marines and the V.A. and nuclear blasts, he was loveable and worthwhile. Now, entering into the final stages of radiation poisoning, he wondered, "What am I here for?" It was this moment that — however humble a gesture — I decided to accept Manuel Cordero's proposal of marriage.

CHELLIS GLENDINNING won the New Mexico Council for the Humanities 1989 First Times Award for Short Story Writing for this story — with the title, "The Interview". To mark the award it was read on KUNM-FM Radio, Albuquerque NM. In addition to being The Journal of Wild Culture's Editor-on-the-Lam, Chellis is the author of eight books, the latest being Las relaciones de objetos (La Paz BO: Editorial 3600, 2018) and The History Makers: Meetings with Remarkable Bohemians, Rebels, and Deep Heads (New York: New Village Press.), to be published in 2019. She lives in Chuquisaca, Bolivia.

Add new comment