TORONTO — Age of Fracture is a ‘big book.” It was penned by Daniel Rodgers, an intellectual historian of America, and professor emeritus at Princeton University. In 2012, Rodgers’ tome made him co-winner of the Bancroft Prize, a prestigious award for books about the Americas or diplomacy. Since its 2011 publication, a mini-industry of criticism and learned discussion has surrounded Age of Fracture, and the accolades and intellectual scrutiny are justified. Rodgers deploys an unparalleled ability to look from on high at discernible shifts in American cultural discourse from approximately 1980 until 2010.

My purpose here is to review the central strands of Rodgers’ powerful argument while considering current trends that sometimes buttress and sometimes challenge his thesis. Needless to say, Rodgers cannot be held accountable for analysis after the 2011 publication of his book. However, its strength and influence legitimates mulling its arguments some five years following its initial publication.

They believed in American exceptionalism, of the “shining city on a hill.”

As the 1960s began, elites in the United States forged a broad consensus over its mission in the world and its duties at home. American elites overwhelmingly agreed that the Soviet Union posed a security threat and a denial of democratic mores. Such Americans largely believed in American exceptionalism, of the “shining city on a hill.” They even concurred about some American foibles. For example, there was a broad consensus about the need to end racism at home. All of that began to fray with the debate over Viet Nam and the explosion of race tension in the aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., in 1968.

Rodgers argues that the American failure in Viet Nam, followed by the perceived weakness of President Jimmy Carter, gave rise to a counter-revolution in American thought. Make no mistake, this is an American book. It delves profoundly and cleverly into the interplay of political, media and academic discourse in a period that Rodgers frames as an “anti-Keynesian counter revolution.”

Rodgers asserts that God was re-born in the form of the free market as the Jimmy Carter presidency foundered and former Hollywood actor and California governor Ronald Reagan strode into the public sphere. With Reagan’s election, Rodgers asserts, a coalition of right-wing think tanks, White House advisors and fellow travellers in academia re-framed the argument for American exceptionalism. The country had lost its soul, so the argument went, in weak-kneed military policy and ineffectual social democratic policies in welfare, education and race relations that fostered dependence.

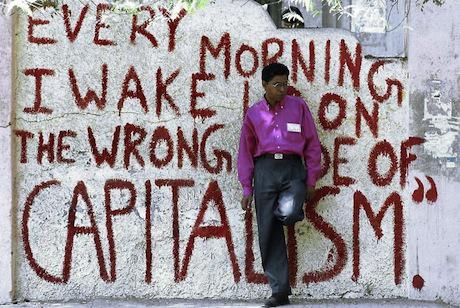

Image credit. >

Through Rodgers’ eyes the ascendancy of a revitalized right-wing, market-loving intelligentsia surrounding the Reagan presidency amounted to a “anti-Keynesian counter-revolution.” Its evangelists believed the market could do no wrong. American satellites such as Chile and Argentina needed to get with the programme and undergo “shock therapy” to wean themselves from social democracy or, worse, Latin American variants of Marxism.

Margaret Thatcher became a revered icon. Ronald Reagan, despite some transparent wobbles towards accommodation during his term as governor of California and in his presidency, was put on a pedestal as an unwavering champion of unflinching, inexorable market forces which, according to its zealots, would result in greater wealth for all.

He draws a link between the classic Tory concept of Burkean “little platoons” . . .

Rodgers takes no prisoners in his scathing review of presidential advisers such as the political advertising and media guru Michael Deaver and anti-Keynesian economists, like Milton Friedman, who achieved almost cult status among worshippers at the alter free markets. Rodgers describes the period as a victory for an elitist counter-intelligentsia.

This particular trahison de clercs (betrayal of the intellectuals) — to use Julien Benda’s memorable phrase about the unthinking embrace of nationalisms by intellectuals in the lead up to World War II — eventually foundered. America would back off the market-as-religion ideology, to some extent, with the defeat of President George H. W. Bush by Bill Clinton in 1992. Economists like Joseph Stiglitz regained favour with his highly developed and resounding put-down of “market Bolsheviks.” Jumping on a mild recession of the George H. W. Bush presidency, Clinton advisors proclaimed “it’s the economy stupid” and steered the campaign to echo an earlier period when activist government had legitimacy. However, the anti-Keynesian impulse was more than a matter of the Republican-Democrat divide; under Clinton, free market ideology granted big favours to Wall Street that contributed to the dot.com crash that immediately followed Bubba’s second term.

Image credit. >

Impressively, Rodgers does not de-bunk and ascribe blame. For instance, he is tuned to ways in which the right, sometimes intelligently, spoke to Americans in a way the left had abandoned. Rodgers draws a link between the classic Tory, indeed Burkean concept of “little platoons” to describe how both Presidents Bush appealed to the family, religious groups and local organisations to nurture community self-help as an antidote to big government fixes. George H. W. Bush evoked “a thousand points of light” as an alternative to the intrusion of a nanny state.

The broad acceptance of the charter school movement by Republicans and Democrats alike is an example of how the right’s ideology moved the needle of American acceptance of a retreating state. Even President Obama’s successful campaign for an expansion of available health care, by enlisting and nudging private insurers while creating profit opportunities for them, is also perhaps a legacy of the age of fracture Rodgers describes.

There are a number of tentative observations to be made and questions to raise by virtue of writing five years following the publication of Rodger's book. He ends with the attacks of September 11, 2001 and their patriotic aftermath. America, he argues, was temporarily re-united in a surge of patriotism that transcended party affiliation and ideology. I wonder how he would now assess the polemic between champions of the apparatus of the security state that emerged in ‘The War on Terror,’ and the followers of its opponents like Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras and Edward Snowden.

The fissures speak to disagreements about climate change, inequities of income, and the struggle between security and privacy in a digital age . . .

One of the best things in the book is how its author brilliantly describes a period of ascendancy for the American right, which begs the question: How would he account for the unlikely rise of Bernie Sanders, an unvarnished American democratic socialist, who is waging a credible campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination against establishment figure Hillary Clinton? Has Sanders tapped into “little platoons” of American environmentalists, post-secondary students, local economy advocates and anti-imperialists that would otherwise remain outside the traditional political arena? At this juncture, Hillary Clinton’s anticipated coronation might face a serious threat from the Sanders campaign. Speaking of fracture in the US, while Sanders is making an impact on the left, what remains of a Republican centrist establishment has been overwhelmed by the unpredictable insurgencies of Donald Trump and Ted Cruz in the quest to find a Republican presidential candidate. Fractures to the left and right, Dr. Rodgers!

And, looking beyond the US, how to account for the recent success of socialist Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the British Labour Party? After all, Margaret Thatcher had inspired Reagan, and Tony Blair was labelled 'Bush’s poodle' over the invasion of Iraq. Could an electorally significant segment of UK opinion now be veering away from American political leadership? And here in the colonies, what would Rodgers make of the unlikely rise of a social democratic government with environmentalist leanings led by one Rachel Notley in the oil rich (and oil dependent) province of Alberta?

If one extends Rodgers’ gaze into the present and regards the US and countries profoundly influenced by American thought, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, one sees that the fracture and disaggregation of which Rodgers wrote has continued. The fissures transcend Cold War ideologies. They speak to disagreements about climate change, inequities of income, the struggle between security and privacy in a digital age, and the response to the flight of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people across Europe’s borders as the Middle East disintegrates. Responses to these dilemmas will be at once ideological and unpredictable. Perhaps in 5 to 10 years a worthy successor to Daniel Rodgers will train a penetrating gaze on the years from 9/11 up unto our present crises.

This article was previously published in The Journal of Wild Culture, July 26, 2016.

JAMES CULLINGHAM is a journalism professor at Seneca College and documentary filmmaker in Toronto. He is the director and producer of In Search of Blind Joe Death — The Saga of John Fahey (2012) and executive producer of The Pass System (2015), an historical documentary film about segregation of Canadian First Nations people.

Add new comment