When my parents moved to the Orkney Islands, some thirty years ago, they knew little of what they were letting themselves in for. They had met in 1975, in the Gloucestershire school where my father was teaching biology. He wore a purple velvet jacket and would occasionally bring his pet squirrel called Charlie along to class. For some reason this kind of eccentricity was something that one of his pupils, my mother, found irresistible.

Over the course of a year, their secret relationship became increasingly obvious to everyone around them. My mother’s parents, needless to say, weren’t exactly thrilled. Despite the objections of friends and family, they couldn’t be kept apart. With very little money, they eventually set off in search of a new life. Following the birth of my eldest sister, they packed their possessions into an old ambulance and drove towards the northern-most tip of Scotland. Looking across the Pentland Firth, Orkney was just about visible, hovering above the British Isles like a storm-battered halo. One short boat trip, and eight years later, I was born on the western side of the islands, the last of four children and the most promising goat herder of the lot.

By the time they settled in Orkney, my parents had become increasingly disillusioned with life’s conventional paths. Partly for this reason, and partly through necessity, both their lives and ours became something of an experiment. We lived without electricity or television, without formal education, and with little access to popular culture for the best part of two decades. Instead, my siblings and I spent most of our time exploring our natural surroundings or helping with the growing and hunting of food. During long summer walks, father would provide us with the names of birds.

“Great Skua!” he would cry, pointing an expert finger to the heavens.

We took note.

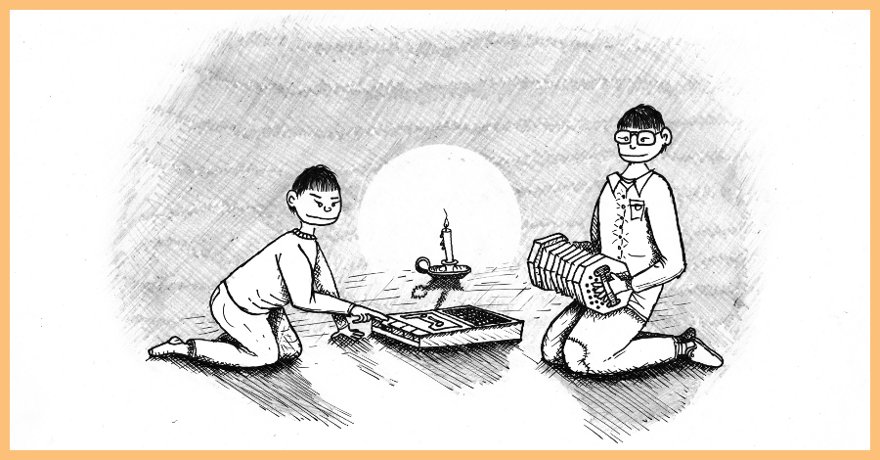

As winter closed in, the days grew shorter and the weather more wild. In the midst of a storm the house would creak and groan like a glacier slowly on the move. Trapped inside, we took refuge in our own imaginations. In the evenings we sat around the fire listening to old episodes of the Goon Show, or records by Tom Lehrer. The flames threw strange shapes across the walls. I watched them, mesmerised. In these moments, what I was hearing and what I was seeing would often become strangely united. Sometimes, when a human life wasn't enough, I'd turn myself into a cat, lurking under the kitchen table and waiting to pounce on the nearest pair of ankles.

While these forms of entertainment were satisfying in their own way, there was particular excitement when my mother bought a second-hand cassette recorder. It looked like a flattened brick, with a big red “Record” button shaped like a block of Cadbury's chocolate. My brother and I were soon recording our own amateur radio shows. One of our programmes was called “Southerland's Cocky Noises” – an assortment of strange and exotic sounds. We presented the show ourselves and it was never quite clear who “Mr Southerland” – or "Mr Southerland’s Cocky" as he was also known – actually was. I rediscovered some of these recordings several years later. At one stage I recall how I had picked up a little noise while "trodding along the south banks of Africa". This noise had been “looking sort of distressed”, and so I’d picked it up and decided to give it a little hug. “It stayed in my pocket”, I continued, "and this is a recording of it". What followed was an inhuman cacophony of squeals, chirps, and growls. This effect was achieved mainly by pushing on the pause button with varying amounts of pressure as we recorded. In this way, our voices would be slowed down, sped up, and generally distorted beyond all recognition. At another point, my brother imitates the sound of a "typewriter who's just come home from the seaside and is very depressed because his funnel has just broken".

With none of us at school, moments of peace and quiet could be hard to come by in the Driver household. For our parents, it must have been a lot to endure. Before they could have any privacy, my siblings and I would have to be rounded up and untangled. Occasionally, after they had sent us upstairs for the evening, my mother would slip into a revealing dress while father applied some Brut cologne and did his best to look like the man she'd met two decades earlier. Since he hadn't updated his shirt collection since the late seventies, this wasn't difficult. Every hour or so, my mother would run upstairs with offerings of crisps and Coke, exotic delicacies that we rarely had the opportunity to experience. With such generous gifts, we knew they must be up to something. Thankfully, these lapses into civilisation were only temporary. By the morning, mother would be back in her milking scarf and father in his overalls. Providing the weather was good, I'd be in one of my usual positions, hanging off a branch or upside-down in a ditch.

Next up: Vol II, The Height of My Seat, to be published Friday 17th January!

All illustrations by PM Driver

Comments

I love this story. It is

I love this story. It is great to get a momentary insight into the life of young Merlyn and to recognize that some of those eccentricities have not faded in adulthood.

Add new comment