By the time I was about thirteen, mains electricity had been installed at Newtonhill. With my father now in his seventies, central heating and other modern comforts had become increasingly hard to resist. Prior to our connection to the national grid, we'd made do with candles, oil and paraffin lamps, a wood-burning stove and an open fire. There'd also been an old generator in the garage that was capable of powering several lights inside the house. It wasn't often used, but on special occasions we got to witness what seemed like a miracle. My father would wrestle with the big greasy wheel, turning it faster and faster until the engine sparked and burst into life. Owning a generator sometimes had its advantages. My mother fondly recalls one of Orkney's huge winter storms, during which the electricity went down across much of the island. By the evening, everyone's home was in the dark apart from ours, standing out against the horizon like a lone star.

One of the reasons why we didn't use the generator very often was that it was extremely unreliable. On one night, it wouldn't stop and the lights inside – typically quite dim – grew steadily brighter. The engine, which usually chugged away reassuringly, was racing as if we'd spiked its fuel with espresso. It became so hot that we were worried it was going to explode. Not knowing what to do, we eventually called the farmer who lived down the road. The only way to stop the engine, he told us, was to stop the wheel. After some deliberation, he launched a fence post between the spokes at a pre-arranged angle. It lodged tight and the machine slammed to a halt.

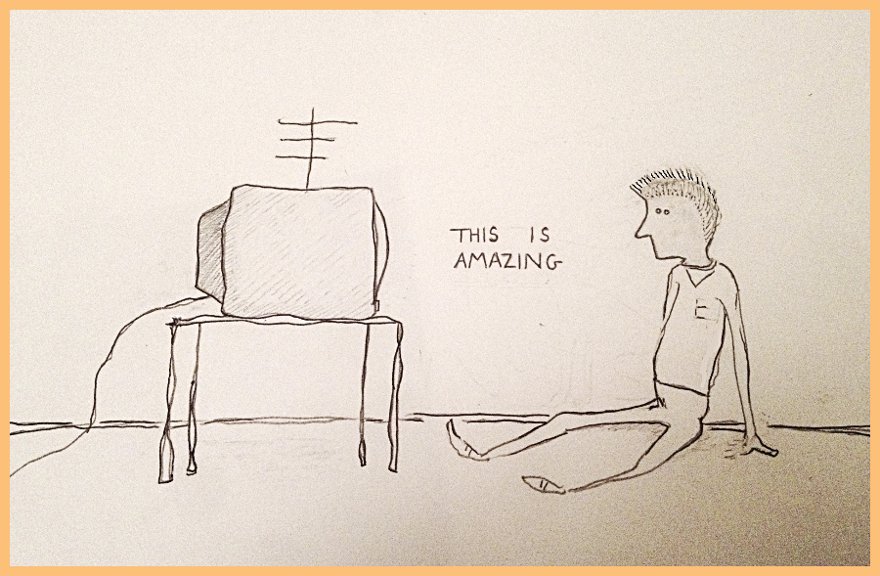

Given my fascination with electricity, you can imagine how intrigued I was by television. The first time I remember watching one was in 1997 when I was almost ten years old. My brother and I had come across an old black and white set in the local skip and brought it home. We fired up the generator and plugged in our new toy. The screen lit up and a fuzzy image appeared of a coffin covered in flowers. It was the day of Princess Diana's funeral. Unfortunately the picture kept jumping between frames. After some experimentation, we realised that the best solution was to sit on the floor, facing the television with our feet pushing forwards and touching it. For some reason, this stabilised the picture. For the next hour or so we stayed frozen, watching the spectacular ritual of a public funeral unfold in all its glory.

All of a sudden, places seemed to be moving closer and further apart almost by themselves.

My parents haven't always been very trusting of television. They seemed to consider it a dangerous habit, akin to drinking alcohol or taking illegal drugs. For this reason we were only supposed to watch educational programmes such as natural history documentaries and the news. In reality, I was so mesmerised by my new discovery that everything I watched seemed deeply profound. I quickly became an addict. My siblings and I watched whatever we could. One of the first cartoons I saw featured a set of dancing knives and forks. I was baffled. We watched soap operas, chat shows, wildlife, weather forecasts and anything else that contained someone or something we hadn't seen before. My favorite programmes were those featuring exotic animals (or teenage girls). My father and I would compete to name every animal we saw, and he shouted out furiously at any discrepancies in the narrative.

"CHIMPANZEES ARE NOT MONKEYS, THEY ARE APES!!!", he would bellow. It was very satisfying.

One of the reasons why I found wildlife programmes so beautiful was their sweeping soundtracks. The music made nature seem all the more emotive; all the more breath-taking. I fell in love with Bengalese tigers and the wildlife of India partly because of the sitar.

Watching all of this television opened up the world to me like never before. All of a sudden, places seemed to be moving closer and further apart almost by themselves. Despite a sense of suddenly being cast adrift, I also found myself being dragged with some certainty towards a major realisation: I wanted to go to university. This was for two main reasons. Firstly, I wanted to live the student life that I'd seen on soap operas such as Hollyoaks and Dawson's Creek. More importantly though, I wanted to emulate my heroes – people like David Attenborough and Steve Irwin; intrepid explorers of planet earth. I used to pretend to be a wildlife TV presenter myself, charging about the countryside in search of 'elusive' and 'dangerous' creatures. Orkney, however, isn't exactly famed for its dangerous animals, and so I had to attribute savagery to small unwitting creatures such as moths, rugby-tackling them in bushes or simply observing from a safe distance.

I knew, of course, that kids don't just go straight to university. Before they do that, they have to prove themselves suitably intelligent, or at least capable of passing exams. Having had no formal schooling, that was something that neither I nor my siblings had done. There was only one thing that I could do. At the age of fourteen, it was finally time to join the rest of Orkney's teenage population, in the classroom.

Illustration by Merlyn Driver.

Next up: Vol X, to be published Friday 31st May!

Add new comment