The island of Hoy lies just south of the Orkney mainland. It has its own climate and its own rhythm. In the north and west, Hoy feels more like the Highlands than the rest of Orkney – there's even a small patch of native woodland (the most northerly in the British Isles) clinging doggedly to life. When they first came to Orkney, my parents lived on Hoy in a seaside cottage called Bulwark. My mother, who was only in her twenties at the time, often found the sense of isolation unbearable. She'd to walk for miles, just hoping to find someone to talk to. Every croft she came across, though, seemed to have been abandoned. It was as if the island had inflicted a strange curse upon its residents.

Exhausted of all other options, she'd usually end up talking to the seals. In the rare instance of her meeting an actual human, she was terrified – despite her loneliness – that it would open its mouth and attempt to speak to her (at this point she could still barely understand a word of the Orkney dialect). Although an old couple lived just a few fields away from Bulwark, they hid away inside their croft like the survivors of a mysterious jungle people. When they died, an English woman moved in, along with her sizeable collection of male animals – a stallion, several billy goats, cockerels, drakes and a ram. According to my mother, she spent most of her time crying. There were two kinds of people on Hoy; elusive locals and eccentric incomers. My parents, while not as crazy as some, undoubtedly belonged in the second category.

Although Hoy is an incredibly beautiful place, I've always found it strangely oppressive. This might have something to do with the history of the island, and the stories I've heard that accompany it. Halfway down the east coast, for example, you'll find the grave of a woman named Betty Corrigall. Back in the late 1700s, when Betty was a young woman, the sailor with whom she'd fallen in love left the island to go whaling. Following his departure, Betty discovered that she was pregnant (out of wedlock) with his child.

Heartbroken and castigated by the locals, she tried to drown herself, but it didn't work; she was spotted and quickly dragged ashore. Her suffering, though, was to continue. Days later, she was discovered hanging in a nearby barn. By committing suicide, Betty was denied the right to a standard Christian burial. Instead of a kirk yard, her final resting place was an unmarked and isolated grave, situated on the boundary between two parishes – unconsecrated ground.

For many years she lay there, forgotten beneath the heather, until, in the 1930s, a couple of men who were out cutting the peat came across the grave. They were shocked to discover the body of a young woman, preserved almost perfectly in the boggy ground.

Although she was later reburied, Betty made several further appearances during the Second World War. “The Lady of Hoy”, as she became known, proved a welcome distraction for the soldiers stationed on the island (Britain's largest naval fleet during the War was situated nearby in Scapa Flow). Exposed to the air, Betty's body began to deteriorate, and a slab of concrete was placed over her coffin. Finally, in 1976, a simple fibreglass headstone was erected (the peaty ground wouldn't support the weight of a proper gravestone). “Here,” it reads, “lies Betty Corrigall”.

A rather ill-looking cormorant made off behind the bothy, dragging its wings through the puddles.

Several years ago, a good friend and I were camping together at Rackwick Bay on the other side of Hoy. What happened there will stay with me for a long time. Kirstie was a recent arrival to Orkney when we first met. Although she'd grown up in Southeast Asia, she used American slang and generally had the style and swagger of a female Marty McFly. Her father – an Orcadian, born and bred – had been living for many years in Brunei, and had returned with his family to the island where he'd been raised.

One crisp morning Kirstie and I boarded the ferry from Stromness (one of Orkney's few towns) to Hoy. The only other passenger was a softly-spoken, middle-aged man with a pair of binoculars and a friendly, well-worked smile. It wasn't long before we got talking. He was a poet, he told us, travelling around the Northern Isles in search of inspiration. Hoy, I assured him, wouldn't disappoint.

When the boat reached the pier, Kirstie and I set off for Rackwick on our bikes, while our new friend began the journey on foot. By the time we arrived on the other side of the island a major storm was brewing, and we were relieved to see that a fire had been lit in the bothy above the shore. We set up our tent and joined a couple of backpackers who were sheltering inside. They introduced themselves as Elodie and Isabelle from Paris. For the next half an hour or so, they told us of their adventures around the islands, with Kirstie, who speaks a little French, acting as translator. Outside, the wind was steadily building. Much of the smoke from the fire was being sent back down the chimney, and as time went by, it became increasingly difficult to see from one side of the room to the other.

After a while, the door creaked open and the missing poet, looking thoroughly bedraggled, stumbled in. We shuffled along and invited him to join us next to the fire. “I can't,” he snapped. “I'm allergic to the smoke.” I was startled: he was no longer speaking with an English accent, but with a thick Australian one. And it wasn't just his accent that had changed; his whole demeanour was that of a different person – it was as if he had been possessed. Kirstie and I looked at each other with confusion. Neither of us could believe that this was the same man that we'd met on the boat barely an hour earlier.

Before we could think of anything to say, he was reaching for the door. “I'm going for a walk,” he muttered. He left the bothy with a wall of sea spray rolling in off the bay, and torrential rain already flooding the path. As soon as he left, we began discussing what on earth had just happened, and whether or not to call the coastguard and report the poet missing.

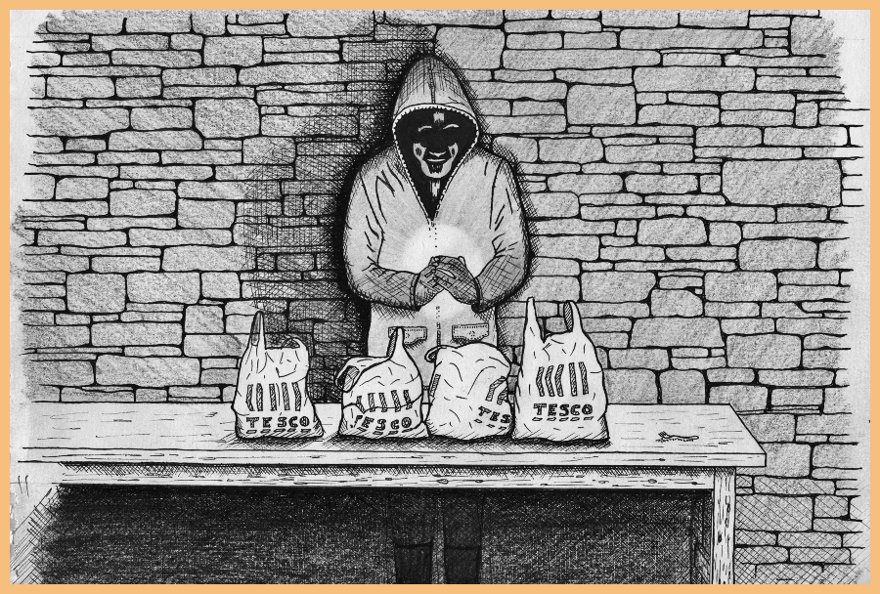

Some hours later, completely dark outside and with the storm showing no signs of abating, we heard the door handle turn once more; the poet was back. He walked into the room holding a couple of plastic supermarket shopping bags in each hand. There was a table at the far end of the room, and he walked over to it and placed the bags down carefully in a row. Considering there wasn't a single shop for miles, we were baffled as to where they'd come from. I asked him if he was okay, but this time there was no answer. He turned to us from behind the table, his hood still up, his hands clutching an object tightly against his chest. A strange red light was glowing through his fingers, and shining up onto his face.

“We can't stay here,” Kirstie whispered. I couldn't have agreed with her more. We rose from our positions and headed tentatively for the door, the poet watching our every move. Out of desperation, I tried making light of the situation. “So...” I said, as calmly as I could muster, “you've found a shop!”

This time, he spoke with a gravelly American accent that sounded like it was from somewhere in the Deep South: “I'm just linin' up my fuckin' bags,” he growled. “You got a fuckin' problem with that?”

Neither of us responded. Trembling with fear, we ran outside and set about dismantling the tent as quickly as possible. A rather ill-looking cormorant, disturbed by the commotion, made off behind the bothy, dragging its wings through the puddles. Further up the valley, a light was shining from someone's window, and we set off with the French girls in its general direction. It wasn't long before we heard a voice behind us. “Bonsoir folks!” he screamed into the wind. “Fuck you all!”

I wasn't sure whether he was following us or not, but we weren't taking any chances. We ran from the beach – through the stinging rain, clambering over fences and wading through boggy marshland – until, finally, we reached the house. The door was answered by a rather frightened looking family who peered out at us suspiciously. We did our best to explain what had happened, and they brought us some hot tea in big red and blue plastic cups. When you're frozen stiff, there's something incredibly satisfying about drinking tea from a plastic cup.

It was getting late, and they suggested that we pitch our tent at the bottom of the garden. It was only meant for two people, but somehow we managed to squeeze all four of us inside. I lay awake until the early hours, squashed against the side of the tent and expecting a knife to slash through the plastic at any moment. But it never came.

By the morning, the valley had been enveloped in a blanket of thick fog. Once it had cleared, we returned to the bay to collect the rest of our things, worried that the poet would be lurking in wait. Our fears though, were unfounded: he had disappeared, and the bay, as if sedated during the night, had become quiet and calm.

Next up: Vol V, Of Meat and Men, to be published Friday 1st March!

All illustrations by PM Driver

Add new comment