Evening at Dacheng Flour Factory, venue of UABB. (Courtesy UABB.)

SHENZHEN, CHINA — In 2008, city dwellers outnumbered rural folk for the first time, and by 2050, there are forecasts that humanity will be 70% urban. This puts cities and how we live in them at the top of our survival agenda, up there with issues (related anyway) like climate change and biosphere degradation.

So we need to think about the cities of tomorrow, and today, the best place to do that is in a city with hardly a yesterday. The Urbanism\Architecture Bi-City Biennale (UABB) in Shenzhen, which I visited last year, is about urbanisation everywhere.

When we picture Chinese megacities, we think of skylines built at breakneck speed, endless housing megablocks, super-luminous, night-time downtowns and air like soup by day. Apart from the air (which is nowhere near as polluted as, say, Beijing), all these things that define contemporary urban China began in Shenzhen.

The very energy of humanity is not so much in the grand visions of planners and architects as down in the backstreets and alleys . . .

When Deng Xiao Ping unleashed Chinese capitalism in China's first Special Economic Zone there in 1980, Shenzhen had about 30,000 people living in fishing villages. Now it has around 10 million, not counting more millions who have no residential status. To me, this certainly feels like the future; the first time I woke up there in 2011 and saw the streams of smartly dressed commuters rising from the spotless, shining Metro into a cityscape of Flash Gordon skyscrapers, I wondered if I was in a sci-fi movie. Shenzhen has had dark moments, from aggressive neighbourhood clearances by developers and heavy police reactions when labour unrest has flared, to the landslide of construction rubble that killed at least 69 in December 2015. But it is also a city that is spectacular, clean, complex, active, efficient — and still expanding.

But for the curators of UABB, Shenzhen isn't tomorrow's city at all. Aaron Betsky, chief curator, says “we need to think about making better use of what we already have”, which sums up the Biennale's theme of 'Re-Living the City'. The other curators spell it out. Doreen Heng Liu says that after 30 years of high-growth urbanisation, China “has seen a lot of issues” from pollution to food security. Alfredo Brillembourg looks around and asks, 'Are these the cities we really want?” Hubert Klumpner says “What’s going on is a mortgage for the future.”

Embodied Pelt (left) and Symbiotic Village (right) are two installations in UABB's Collage City zone. (Courtesy UABB.)

Liu's section of the Biennale examines the present and imagines the future for the Pearl River Delta region (which comprises not just Shenzhen but Guangzhou, even bigger as China's third city), Hong Kong, and a vast spread of other settlements and factories around them. Some utopian visions aside, something big emerges from it. However unprecedentedly the world changes around it, humanity adapts, whether in edge-villages being overwhelmed by urban spread, or in the jumbly, chaotic housing crowding in the shadows of skyscrapers literally shining gold. The very energy of humanity is not so much in the grand visions of planners and architects as down in the backstreets and alleys where food is cooking, workshops working, and goods being traded. This is the unplanned, ad-hoc city.

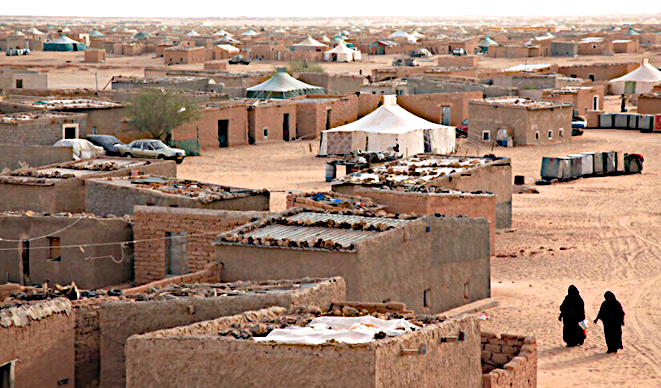

Brillembourg and Klumpner's section goes beyond China, with exhibitions showing the sheer diversity of what makes a city and what cities can be made. One show by Manuel Hertz looked at how makeshift desert camps in the Western Sahara, an unrecognised country with a slow-burn war, are becoming urban. Again, there is ad-hoc organisation here, the outcome of an inexorable current of human endeavour. That ad-hoc organisation of taking things and making them better is celebrated in Betsky's own section, where various parties have constructed (mainly) organic installations from found local material.

Shenzhen housing beneath golden skyscrapers. (Photo from WISE Architecture's 'The City that Re-lives its Memories' at UABB).

There is much, much more to the UABB, not the least of which is the brilliant re-use of an abandoned flour mill as its venue (in a redesign by Doreen Heng Liu). It has had astonishing speakers, too, probably none more so than Chendu architect Liu Jiakun (no relation), who after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake made the very rubble of buildings it destroyed into 'rebirth bricks' with which to build anew.

This is not to say that visionary urban design has no place in the future. In Shenzhen, the sweep of the vast, monumental but colourful Civic Center, the thrust of the new 599m-high Ping An skyscraper (the taller World Trade Centre tower was 415m), or even the bright new Metro system already carrying a billion passengers annually, can take your breath away.

But the take-away from UABB is that tomorrow's cities can be built not from scratch but from what we already have. Ultimately this is ingenuity and adaption at a human scale. ũ

This article was first published in The Journal of Wild Culture in January 13, 2016.

HERBERT WRIGHT is a London-based author and journalist specializing in architecture and art, and a Editor at Large of The Journal of Wild Culture. He studied physics and astrophysics at the University of London. He is currently a contributing editor of Blueprint magazine, and contributor-at-large to Design Curial. www.herbertwright.co.uk

El Aaioun in the Western Sahara, in Manuel Herz's UABB study. (Photo © Manuel Herz)

Add new comment