Ariadne, Arthur Streeton, 1895. Oil on wood panel 12.7 x 35.4 cm.

LONDON — On a recent trip to London, on one of those interminable escalator rides — up and up and up — I caught sight of an extraordinary poster. It showed a painting of a sun-baked beach with sensuously leaning trees in the foreground, in beautiful light, very Mediterranean, and behind the trees and the beach, rolling waves on a sapphire sea (the image above). It was the kind of image that made me want to be there, and I was pulled out of the blurry chaos of London’s tube to read the fine print. “At the National Gallery — Australia’s Impressionists.”

A friend and I went the next day, and what we saw made us wonder why it took the National Gallery so long to mount this exhibition; most of these paintings had been done 100-125 years ago. Whatever reasons for the delay — colonials must wait their time, perhaps? — these paintings were a spectacular discovery, both as landscape paintings with no specific context and as documents of the harsh land in the late 19th to early 20th century on the smallest continent.

“Australia’s Impressionists” focuses on the paintings of four artists, Tom Roberts (1856–1931), Arthur Streeton (1867–1943), Charles Conder (1868–1909) and John Russell (1858–1930). All were participants in a distinctively Australian art movement influenced by everything from Whistler’s subtle Nocturnes to painting outdoors as practiced by French Impressionists.

The purple noon's transparent might, Arthur Streeton, 1896. Oil on canvas 123 × 123 cm.

Allegro con brio, Bourke Street West, Tom Roberts 1885-86, reworked 1890. Oil on canvas on composition board 51.2 × 76.7 cm.

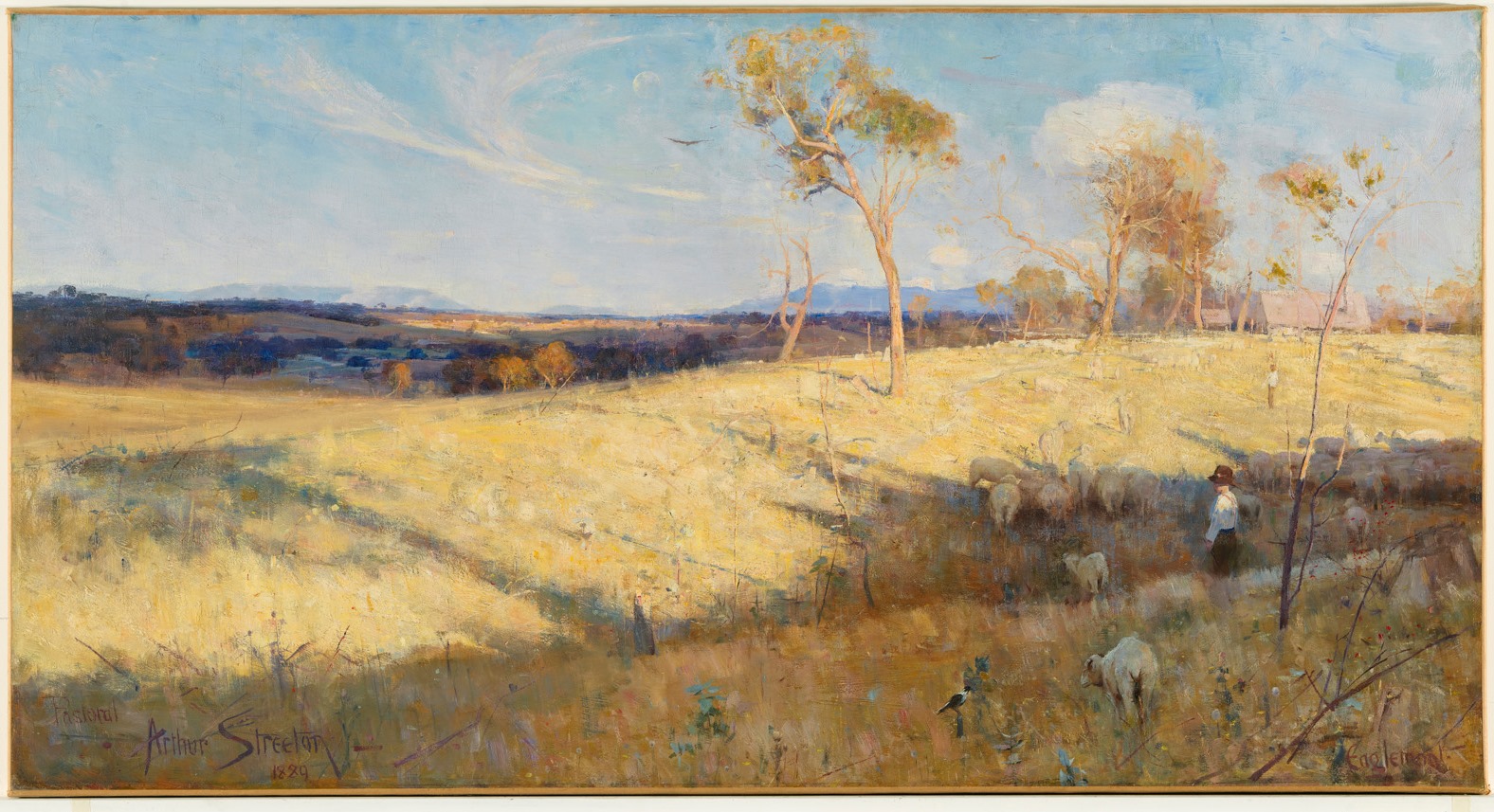

Impressionist art, born in and around Paris, was done largely out of doors, a plein air style made possible by the invention of easily portable paint in tubes. On the other side of the world, in the Heidelberg area of Australia, outside Melbourne, Arthur Streeton had acquired an abandoned homestead looking over the Yarra Valley to the blue Dandenongs, a grand spot to practise. Tom Roberts, born in England, emigrated to the Melbourne area as a teenager and returned to England to attend art school. Traveling through Europe, he was captivated by Impressionist styles he picked up in Spain. When he came back to Melbourne in 1885 he urged other painters he knew to limn the landscape to bring out the authentic character of the Australian terrain and climate.

After Roberts introduced Arthur Streeton to Charles Conder of Sydney, over time the three came to be known as principals of The Heidelberg School art movement. They took their swag, brushes and paints off to the developing cities, to drought-baked ridges and gullies, to rural parts where flies, dust and magpies mix with sheep and cattle, and concentrated on getting the paint mixture that captured the light of Australia, not Europe.

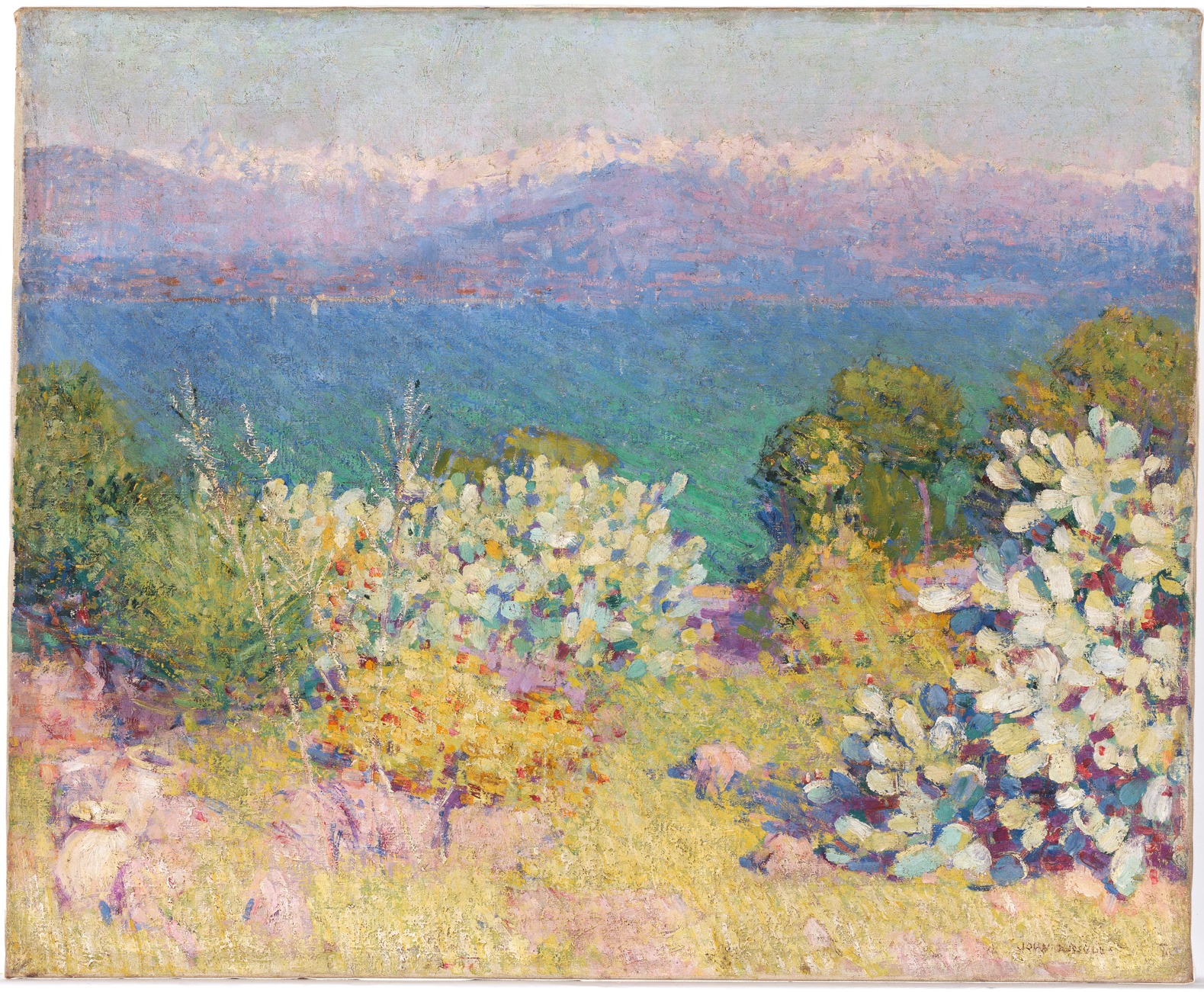

In the Morning, Alpes Maritimes from Antibes, John Russell, 1890-1, Oil on canvas 60.3 × 73.2 cm.

A Clearing in the Forest, John Russell, 1891. Oil on canvas 61 × 55.9 cm.

Meanwhile, Sydney engineer John Russell had left his career, and Australia, to become an artist, ultimately working in France. Of the Australian Impressionists, he is the odd man out in this exhibit; his role was more of the long-distance mentor, keeping the other three fresh on news from the avant garde front, featuring what his close friends Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh were doing at the time. Well admired for his abilities as a colourist, his work brought significant inspiration to young Henri Matisse. But his paintings of Provence and Brittany and frothy seascapes, nurtured along by friend Monet, have not much to do with Australian myth making practised by the others.

Meanwhile, the three Heidelberg School members first showed their self-described ‘Impressionism’ in an 1889 Melbourne show entitled, “9 by 5 Impression Exhibition.” A friend’s tobacconist father donated scores of wooden cigar box lids, measuring 9 inches by 5 inches. These substituted as canvasses for the real-life images painted outdoors — and painted fast. (The show was influenced by a similar one done in 1884 in London by Whistler.) Reaction was mixed, popular with the public but panned by the art press. Streeton, Roberts and Conder fought back, writing to Melbourne’s newspaper The Argus that whatever moves us “is worthy of our best efforts”.

A Quiet Day on Darebin Creek, Tom Roberts, 1885. Oil on wood panel 26.4 × 34.8 cm

A Break Away!, Tom Roberts 1891, Oil on canvas 137.3 x 167.8 cm.

National Gallery curator Christopher Riopelle begins the exhibit with some of these small works. On first viewing they seem unsophisticated, raw landscapes in shade, and the rainy day scenes of city life could have been lifted from European streets. Well, artists have to start somewhere, and of course this is the reward of a well-curated show: that the early works inform the mature ones.

But as the show continues we can see, in the time span from 1884 to 1905, their use of colour became more effective in landscapes they knew well, rather than when they were imitating the work of other painters. Though they caught certain aspects of the birth of this nation (the six colonies federated in 1901, forming the Commonwealth of Australia), they neglected to capture Aborigine life at any given moment. As well, the way they pictured women was in their dainty gowned passivity, lightly stepping in pastel-hued dresses across dusty streets, or reading on a beach holiday, balancing an umbrella on a rainy dockside. Where are the jillaroos, one asks, the young women working on sheep or cattle stations? Not here. Absent of indigenous peoples and the rural woman, the mythic view that the Australian Impressionists painted was — as depicted in A Breakaway!, by Tom Roberts — of the macho stockmen, kicking up yellow dust on horseback, galloping after getaway sheep headed to water.

Departure of the Orient — Circular Quay, Charles Conder, 1888. Oil on canvas 45.1 × 50.1 cm.

On the River Yarra, near Heidelberg, Victoria, Charles Conder, about 1890. Oil on canvas 30.4 x 40.7 cm.

So what became of these four figures who gave Australia its own Impressionism? Having acquired syphilis, English born Charles Conder relocated to England in 1890, where his fortune rose when he married a wealthy widow, but his later work was never as celebrated, except by other artists, as what he painted in Australia. He died in a sanatorium for “the insane” in Surrey. Canberra named a suburb after him in 1991. John Russell, the wealthiest of the Australian Impressionist quartet, eventually moved back to Sydney from Europe after the death of his wife. His great capacity for friendship with Monet could not save his broken heart; he destroyed hundreds of his paintings before he died in 1930. And who knew that one of the most innovative artists of the twentieth century, Henri Matisse, credits John Russell with teaching him colour theory!

Tom Roberts, likely the most ardent defender of his and fellow Impressionist’s works in Australia, best answered the call of his colonial leaders, with an eye to nationhood, who urged him to make “pictures of the true rude life” of white settlement in Australia. His life was celebrated in a 1985 television series, One Summer Again. Arthur Streeton, who had achieved Mention honorable at the 1892 Paris Salon for Golden Summer, Eaglemont, saw it become the first painting by an Australian-born artist to be exhibited at the Royal Academy, London. Somewhat like Monet in Giverny, he painted to the end of his life in his acreage in the Dandenongs.

Golden Summer, Eaglemont, Arthur Streeton, 1889, Oil on canvas 81.3 × 152.6.

Perhaps National Gallery goers in Britain were not ready for “pictures of the true rude life” of Australia’s colonial past until now. But given the British pride and love for Turner, who certainly went outside to work and led the way for all Impressionists, I have to think it’s just insular, Euro-centric thinking about what is significant in art, much in the way the Canadian landscape art movement, the Group of Seven, took a long time to be noticed internationally.

My friend and I, on a brief tour with our choir from Toronto to London, never having been to Australia, never expecting to see Australian Impressionism, never knowing it existed, took a little path to enlightenment. It broadened our view of the essential nature of global community and collaboration, in this case between artists, on behalf of those who love art. Looking at the absence of Aboriginal life depicted in the work of Australia’s Impressionists makes you wonder where artistic development could have taken them, by painting in that gap.

The exhibition Australian Impressionists, at the National Gallery, London, closes March 26, 2017.

MARILYN MERCER is a former instructor in journalism at Carleton University in Ottawa. She worked for many years at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as a producer and manager in radio and television. For radio she was a producer of Morningside and founding producer of Basic Black. She produced a network television special on Alexandr Yakovlev, Soviet Ambassador to Canada, who returned to Russia as architect of glasnost and perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev.

Comments

What a wonderful mini break

What a wonderful mini break to Australia. I became aware of the Heidelberg School when I lived in Melbourne, beautiful works and akin to our Group of Seven, as you've mentioned.

Indigenous art in Australia is in a category of its own, and one you'd appreciate as well.

Thanks for sharing your wonderful discovery!

Add new comment