The ceremonial mask-wearing tradition is resurfaces in the shamanistic techniques of ornithologist and artist Marcus Coates. Coates channels the spirits of dead animals, often plucked from his favourite stomping grounds, to perform ritualistic ceremonies, bringing new age spirituality to unsuspecting audiences - like the residents of a Liverpool tower block scheduled for demolition. Moving from the sublime to the ridiculous, Coates’ majestic horse heads and rag-bag animal masks made way for comedic disguises when the artist transformed himself into 21 species of British moth simply by moulding shaving cream onto his face.

In the manner of the immersive flotation tank, Viennese group Haus-Rucker-Co created bubble-shaped prosthetic helmets for their Mind Expander series (1967-69). By distorting both sight and hearing, masks like “the fly head” altered the perceptions of those wearing them, inviting participants to actively determine space and their position within it. In this Alice in Wonderland mentality, the world itself becomes part of the individual’s topsy turvy vision.

The artist Don Proch furnishes masks and helmets with pencilled home interiors and sweeping wildernesses, honing in on our uncertain position between the macro and the micro. In Delta Night Mask - Homage à Kelly Clarke, named after Delta Beach on Lake Manitoba, the surface of a spacey looking motorcycle helmet features a graphite pitch-black prairie scene. On peering inside, viewers see the same night scene as if through a cottage window, each star in the sky individually lit by a fibre optic cable. These are wearable manifestations of imagined landscapes, psychogeography in mask form.

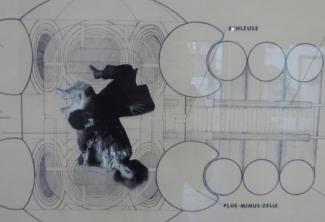

In the artist’s 2011 solo exhibition Trappole del Piensero or “trap for thoughts”, at the Barbara Davis gallery in Texas featured modified fencing masks adorned with miniature embellishments like birds and baubles in abstract arrangements. Designed to be maps of mental constructs, these “exploded diagrams” chart the passage of the artist’s introspection.

In the imitative tradition of Gillian Wearing and Cindy Sherman, Jonny Briggs casts the heads of family members to produce solid wood replicas. Splitting the heads into two halves, like a nut, the artist photographs himself inside the wooden shell, his own face peeking out from within. With the appearance of a resuscitation dummy or ventriloquist’s doll, these masks are “devices of the hidden, restricted and subverted” and enable a revival of the unadulterated self which lies somewhere beneath one’s inherited looks, familial memories and beliefs about the self.

Comments

The debate about the meaning

The debate about the meaning of these and other mask forms continues in Europe, where monsters, bears, wild men, harlequins, hobby horses, and other fanciful characters appear in carnivals throughout the continent. It is generally accepted that the masks, noise, colour and clamour are meant to drive away the forces of darkness and winter, and open the way for the spirits of light and the coming of spring.

In Indonesia, the mask dance

In Indonesia, the mask dance predates Hindu-Buddhist influences. It is believed that the use of masks is related to the cult of the ancestors, which considered dancers the interpreters of the gods. Native Indonesian tribes such as Dayak have masked Hudoq dance that represents nature spirits. In Java and Bali , masked dance is commonly called

Where are they made from???

What are they made from?

We do not know the answer to

We do not know the answer to this. Thanks for your question.

Add new comment