“Y’all can’t stop Mother Nature. If she wants

to come ’n get ’cha, she’ll come ’n get ’cha.”

— Hurricane Katrina survivor, New Orleans

I’m a born storm chaser. Growing up as I did in the middle of a summer storm zone at the southern end of the Great Lakes peninsula, I was witness every summer to hot Gulf air masses blowing north, up the Mississippi valley and spawning terrific thunder-storms over my hometown. I prayed for tornadoes. I stood outside in the wind before the rain, searching the blue-black clouds for a funnel, and, as an adult, I drove toward distant towering thunder-heads, hoping to catch even the briefest glance of a twister. But my wishes were never fulfilled, at least not in the tornado department.

I’d arrived in Grand Bahama late Sunday afternoon on August 21, 2005. After unpacking, I took a sunset stroll along the beach. The air was hot, even in the early evening, and the ocean was calm enough for me to spot a dark patch in the water. Could it be a coral reef? After breakfast the next morning, I strapped on my mask, crouched in the seawater and pulled on my flippers.

I had no idea that water this warm was unusual, even for Grand Bahama in August . . .

The water was surprisingly warm and not only in the shallows. Just the mild exertion of a facedown breaststroke made me sweat, underwater, a decidedly peculiar sensation. (The purpose of perspiration — cooling the body — is defeated underwater, with sweat only pumping more salt into the ocean.) I had no idea that water this warm was unusual, even for Grand Bahama in August and that it would play into meteorological events that were underway long before I landed in Freeport.

Three weeks earlier, around the time I was wondering what I should pack for my trip, the weather in North Africa was conspiring a chain of events that would turn my holiday upside down. And it all had to do with prevailing winds, the northern trade winds in this case, which in turn are entirely a result of the Coriolis effect. [. . .]

The eye wall of Hurricane Katrina. [o]

HURRICANE ALLEY

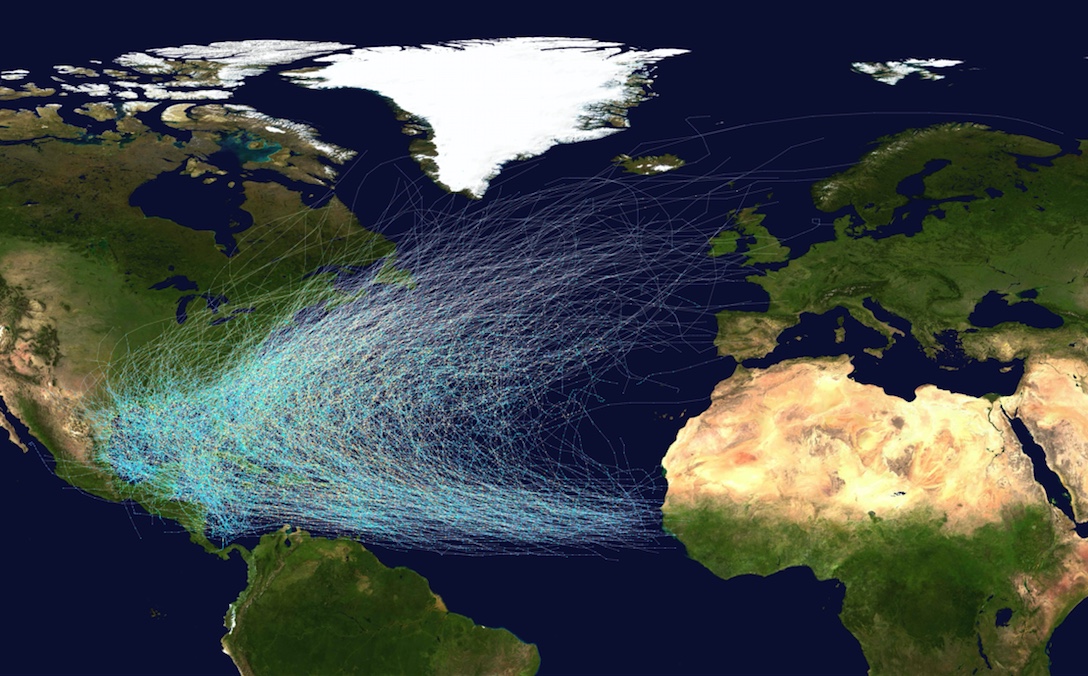

During summer, the tropical Atlantic heats up like brine soup and the trade winds push developing hurricanes west. They grow larger and evolve from tropical waves into tropical depressions and then into tropical storms. Hurricane Alley is like the conveyer belt that runs through the oven of an industrial bakery, only the airy loaves that pass through Hurricane Alley’s assembly-line bakery puff up on moist, thermal updrafts from a hot ocean. Water temperatures should be a minimum of 26.5°C down to a depth of at least 150 feet to properly spawn a storm. During a hot summer, Hurricane Alley can build a storm from its fledgling stage off the coast of Africa to a monster hurricane threatening the North American and Caribbean coasts.

Tropical depression 10 was 1,600 miles east of Barbados when it was given a number, but U.S. forecasters at the National Hurricane Center doubted it would get any bigger because mid-level wind shear had developed, likely to cap the ability of the storm to build a central core. Hurricanes are, in essence, warm-core systems that are stacked vertically. Hobbled by wind shear, tropical depression 10 meandered slowly west for a few more days until by August 14, a week before I arrived in Grand Bahama, it had degenerated and the National Hurricane Center had reclassified it as a tropical low pressure. It lost its number. By the 18th, it had dissipated almost completely.

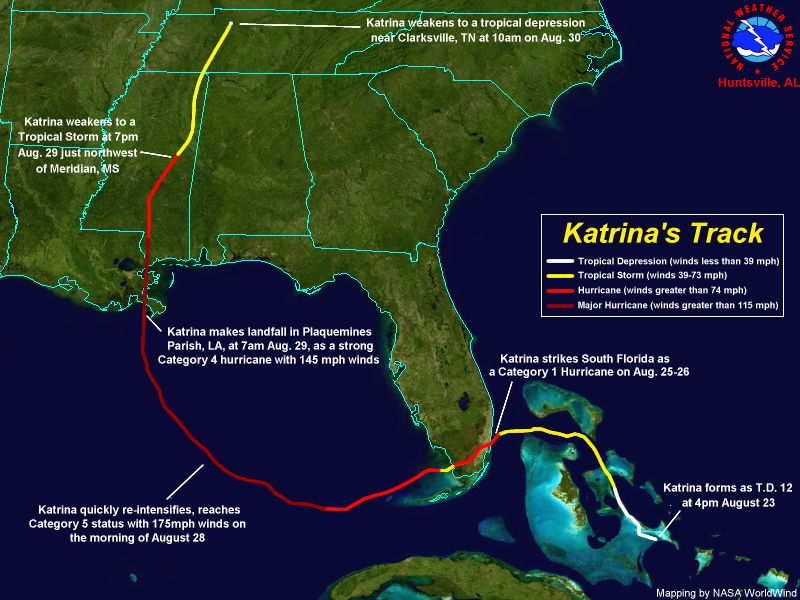

This weak disturbance that was hardly worth tracking — the remnants of tropical depression 10 — would turn into Katrina, and her ability to surprise was about to become evident. Now a disorganized tropical low, it kept drifting westward, wafted by the northeast trades. It entered the ocean north of Puerto Rico a day after I landed in Freeport. There it joined forces with a local tropical low and formed an alarming alliance that caught the attention of the National Hurricane Center. Its QuikSCAT satellite, which measures near-surface wind speeds with a SeaWinds scatterometer (a microwave radar) capable of penetrating cloud cover, had picked up one of the key developmental stages of a hurricane: the lowering of the mid-level circulation to the water’s surface. Wind-whipped ocean spray was feeding warm moisture directly into the hungry storm. On August 23, this new hybrid storm was given a new number, tropical depression 12, and it slid into the Bahamas late the same afternoon.

I had had two lovely sunny days in Grand Bahama before tropical depression 12 struck. On that Tuesday afternoon, the sky clouded over, and in the evening it began to rain. There was some wind but not a lot. During the afternoon, the National Hurricane Center had issued a tropical storm watch. There was a possibility that tropical depression 12 might intensify. The wind was increasing, and the local weather channel was clearly alarmed about the possibility of a tropical storm. Being used to the hysterics of my own local weather channels in Toronto, I was skeptical and figured I’d still be able to go snorkeling the next day.

When steady winds reach 39 miles per hour in a tropical depression, the National Hurricane Center gives it a name and upgrades its status to tropical storm. On Wednesday morning, August 24, tropical depression 12 was given the name Katrina. Well, I thought, at least a tropical storm isn’t a hurricane, and although it was breezy in Freeport, it wasn’t that windy. So I drove to the west end of the island to snorkel at my favorite offshore reef, Paradise Cove. There were few showers on the way, but the air was warm, and, more importantly, when I arrived the waves were not so large that the dive masters had shut down access to the outer reef. I parked, checked in, put on my flippers and mask and swam out with dark clouds looming ahead of me.

By the time I got to the outer reef, I was the only snorkeler and I could hear occasional thunder. The storm was definitely getting closer. Seeing lightning flicker under water, reflected from above, seemed totally worth the risk I was taking. It lent a dramatic, moody ambience to the electric colors of the fish and coral. I finished a circuit of the reef as the wind had begun to pick up. I could hear it whistling in my snorkel. As I came around the southern end of the reef, I noticed a motorboat heading toward me. The driver turned out to be one of the staff from Paradise Cove. “Do you need a ride?” he shouted over the wind. I lifted my mask while treading water and said, “No thanks, I’m fine.” Though actually, it was a bit of a slog getting back to shore. The waves were getting a bit choppy.

On the drive back, I had to negotiate some fairly deep, large puddles — there are no storm sewers on Grand Bahama. Otherwise it didn’t seem very stormy. Late that evening, the local television forecast showed radar images clearly revealing that tropical storm Katrina, which was just south of Grand Bahama, had broken up into three distinct fragments. As a result, the weather advisory was lifted. I went to bed just before midnight on a completely calm evening.≈ç

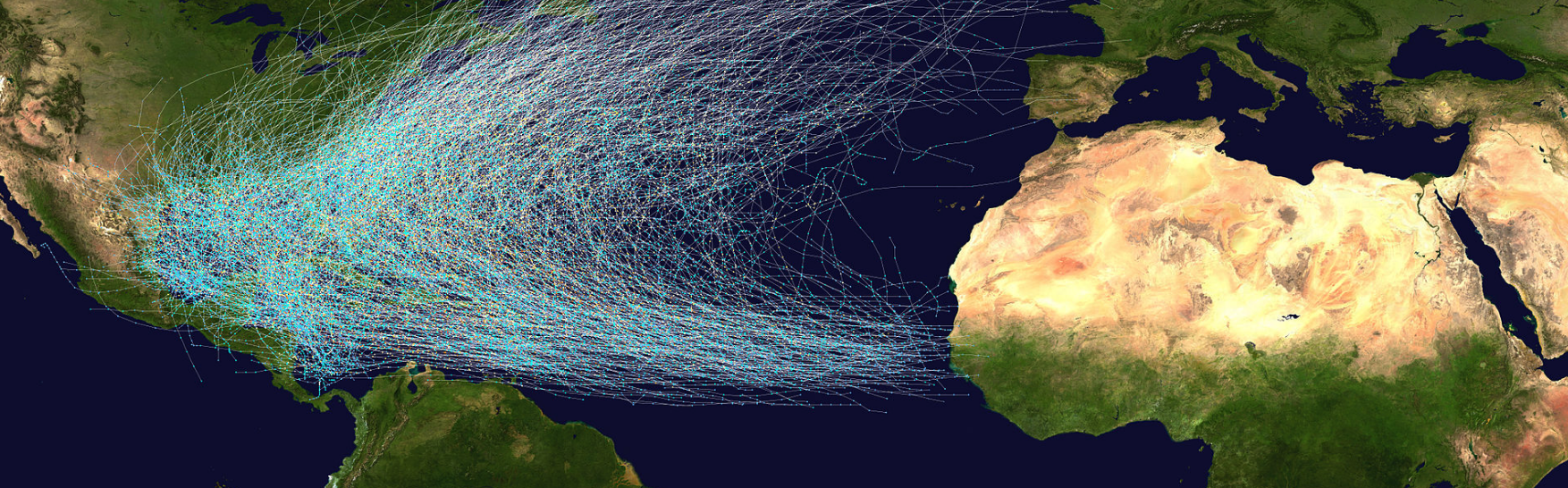

This map shows the tracks of all Atlantic hurricanes which formed between 1851 and 2012. The points show the locations of the storms at six-hourly intervals and use the color scheme from the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.

No one was sleeping at the National Hurricane Center though. High above me, careening through the upper thermosphere in the early morning hours of August 24, the NHC'S TRMM satellite was sending some alarming data back to the nhc command center. The radar was detecting the formation of eyewall clouds south of Grand Bahama. This is where the heaviest rainbands (continuous, linked chains of thunderstorms) concentrate during the transformation from tropical storm to hurricane. At around three in the morning, Katrina opened its eye. ō

Excerpt adapted from 18 Miles: The Epic Drama of Our Atmosphere and Its Weather, by Christopher Dewdney. Published by ECW Press, 2018.

CHRISTOPHER DEWDNEY is a the author of four books of nonfiction and eleven books of poetry. A four-time nominee for the Governor General’s Award, he won the CBC Literary Competition for poetry and has been awarded the Harbourfront Festival Prize. Christopher lives in Toronto, where he teaches writing at York University.

Comments

This essay expands my idea of

This essay has expanded my sense of what a typical nature essay might be. In clear prose, the author helped me understand how hurricanes are formed and the notion of hurricane alley. I loved how the story went back and forth from personal experience to more analytical information about the hurricane and weather patterns.

Add new comment