Inset from Military Village series.

“The impulse to paint comes neither from observation nor from the soul (which is probably blind) but from an encounter: the encounter between painter and model: even if the model is a mountain or a shelf of empty medicine bottles.”

― John Berger, The Shape of a Pocket

As the great digital immigration sets fire to artistic traditions, the old methods smolder — and keep us warm. Learning to play the trumpet or violin, despite few opportunities to make a living at it, is a challenge still embraced. In art, crowds of all ages flock to exhibitions to get the chance to view 150 year-old masterpieces by painters whose code for the natural world still has a mystifying hold on us.

Having just watched an evocative film about the final days of Vincent Van Gogh’s life, Loving Vincent, I was yet again inspired by the cliché of the heroic, possessed artist. As a teenager I'd been enthralled by the letters between Vincent and his brother Theo, and watching the film made me wonder about artists who might be doing the same thing today, 19th-century style. I was reminded of a street artist I had met a few years ago; when I first saw his paintings I heard myself say, “This person could be famous someday.” The observation was based on the quality of his work, but also on my sense of who he was. Ezra Pound referred to such artists as 'serious characters': they possessed what others didn't: a relentlessness to do their work no matter what, to live in a way that put everything else aside.

I think everywhere is beautiful, but it's just maybe more subtle in some places than others.

I hadn't heard from him in a few years, and wondered where he was now. Was he painting, and if so, what? Maybe it had left him: the ego thrust, the self-belief. Maybe he was teaching art in a small college somewhere. “Mouths to feed. Not so much time to paint as before . . .”

I sent and email and heard back from him right away. He was in Taiwan, and painting more than ever.

We had met in New York in 2011 when my son and I were walking into the Museum of Modern Art. Near the entrance was this young man in a paint-splattered shirt and pants — for $50 he would paint your portrait. Lanky, serious, in his mid-twenties, if that, good looking in a man-boy way, he was crouched over a metal card table caked with dried pigment, which also functioned as an easel. His subject sat across from him while he barely moved, his eyes shifting back and forth between the face and the piece of Masonite he was painting on, about the size of a sheet of a paper.

Examples of his work hung on the side of the table. In the words of Lisa Lewis, a lecturer in literature and writer on art and one of the handful of his sitters I contacted for this article, these sample paintings were “in a style that leaned toward Lucian Freud and the German Expressionists.” The strong resemblance to Freud’s wet-on-wet brushstrokes was unmistakeable: radical colors up close that blend into coherence with distance. Indeed, he was once asked, “What are you, the Lucian Freud of 53rd Street?”

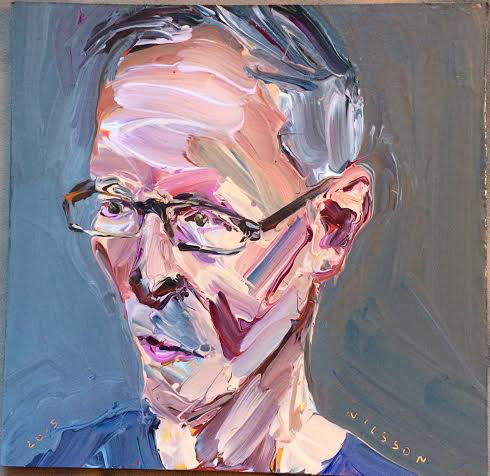

Whatever the comparison — which could be worse than this one — Mark Nilsson could really paint.

"Russell”. 2015. 9” x 9”. Acrylic on bristol paper.

"Sally”. 2012. 9" x 9”. Acrylic on bristol paper.

“It was an experience where you had to put up with two things,” said Richard, a media executive and art collector. “Accept that the portrait was not necessarily flattering, yet reflected the decrepitude, the strange angles and weird unhappinesses that crease your face over the course of a long life. And, sit there for as long as it took, whatever the conditions.”

A productive street artist would ensure that the sitting time was proportionate to the sitter’s patience and the artist’s bottom line. But Mark was a street artist in New York only because it paid the bills. “In the very beginning the portraits took under an hour,” he wrote me recently from Taiwan, “but the more I did them the longer they took. In the end, it wouldn’t have been unusual for me to spend three hours on one — another reason why they became unsustainable. When people would ask how long it would take, I would intentionally be vague. I would say, "It's very hard to say. Maybe something like an hour.”

Last year the English art critic Martin Gayford gave a lecture based on his book, Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud, (Gayford was the man) in which he estimated that over a 9-month period he sat for 130 hours. He also spoke about Freud’s relationship to time: “A lot of the time was spent with Lucian looking around for exactly the right half-used tube of burnt umber or a particular yellow. There was a lot of hunting around and mixing. . . David Hockney said he wondered why Lucian didn’t mix up these colours in advance to save time. Then he thought on a bit and said, ‘Lucian didn’t want to save time. He wanted to take up as much time as possible, looking at the sitter.’ That was part of Lucian’s system of painting people.”

Brought up in Poughkeepsie, a two-hour drive from New York on the Hudson River, Mark describes his family as "lower-middle/working class and not particularly supportive" of his painting. After studying art at college he went to Europe where he learned to make fast portraits in public; when he returned to New York he rented a cheap room to see if he could make a living doing it on the street. For two years, at his spot outside MoMA, he managed to make enough to pay the rent, though "it was never easy."

"Ashbury St”. 2014. 14" x 17”. Acrylic on bristol paper.

"Chaozhou 8”. 2014. 14" x 17”. Acrylic on bristol paper.

While painting Lisa Lewis, Mark opened up to her about life in the city. “He was grateful that a tenant in the MOMA apartment building stored his card table and painting equipment overnight in a storage closet, so that he didn’t have to haul it on the subway every evening. But he spoke with disdain of the tediousness of a job moving boxes at Kinkos’ and the outrageous enormity of his monthly rent for a room he shared with another. He also mentioned his parents' inability to understand his passion for painting, that painting for art’s sake wasn’t a ‘real job’.” This rang a bell for me: my sister and brother and I, who all became artists in one field or another, had a father who declared that "art was an avocation, not a vocation."

His work at MOMA was plagued with the usual hazards of setting up shop on a busy, downtown street. The sudden appearance of competing souvenir vendors or construction crews forced him to abandon his prime location to another across the street, away from the profit stream of tourists flooding into the museum. There was one perk though: he could run upstairs at MOMA to study the work of Cezanne or Matisse, or other favorites: Chaim Soutine, Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, Joan Brown, Fairfield Porter.

“Being on 53rd Street was usually a struggle,” he said, “but there was some exposure that helped.” In October 2012, The New York Times published a story on him. Coming to the attention of such a wide readership, one might expect his career to accelerate. “It just created much more interest,” said Mark. “The months before it was written were really bad. I probably painted as many portraits in the week after that was written as I did all summer.”

His education in painting began in 2005 in the painting and drawing program at the School of Art+Design, Purchase College, 45 minutes outside Manhattan. Michael Torlen, Professor Emeritus at the School, wrote in support of Mark’s receiving the Dean’s Senior Recognition award when he graduated: “Mark Nilsson is an exceptional young artist; intelligent, tough minded, ambitious, and dedicated.”

Artist at work . . . “I don’t paint from photos." [o]

The dedication was clear. In the article Mark recalled running into a former classmate from college who said, “You’re the only one of us I know who’s making a living painting.” Well, enough of a living to pay for a $475-a-month room in Brooklyn in a shared basement apartment, an hour’s subway ride away from 53rd Street. “My first two winters doing the portraits outside MoMA were pretty mild ones, so I was able to tough it out. But the third winter was exceptionally cold and snowy. So I wrote a bunch of emails trying to find opportunities for myself. I was able to set up a few house-calls, where I went to people's homes and did indoor portraits, but that was a hassle, and I never really made much money on the portraits anyway.” Small paying opportunities came up, including a man in a business suit showing him a picture of his child on his phone and asking if he could paint that. “I don’t paint from photos,” said Mark.

“His life-style choices reflect his commitment to painting, above all else,” said Michael Torlen, “and he was a risk taker. He still is.”

Mark ambitiousness came through clearly in our correspondence. Most artists who take a passive, if-it’s-meant-to-be-it’ll-come-to-me approach do so at their peril. Before we lost touch, Mark sent emails with j-pegs of recent paintings. “I know that the idea of taking my portrait project on tour is kind of a wild idea,” he wrote in one email, “but I wonder if you would be interested in that, in me coming to Toronto? I could paint you or whoever would want a portrait, and I could also do a series of landscapes in and around your area.” I admired this. He was taking care of himself. He was casting bait.

One of these emails worked. A friend in Taiwan who he knew from college invited him to visit. Mark took on a job teaching art and English at the school his friend and his friend's wife ran. “I was happy to take it,” he said, “since I didn't particularly want to go back to doing the portraits in New York. I immediately liked painting landscapes. It felt so refreshing and free compared to the portraits.”

With painting a landscape, it doesn't matter if it's bad or if it's an experiment that doesn't work.

Unable to get a visa, he went on the road again, this time traveling to California, Mexico, Switzerland, France, Portugal, Lebanon, Korea, which lasted a couple of years. “Most of that traveling came from taking advantage of offers made by people whose portraits I painted on 53rd street, like, 'if you ever want to paint in San Francisco, I have a spare bedroom.' ”

Returning to New York and more street portraits, he happened to paint a Taiwanese woman who had a house in Taichung, in the center of Taiwan, and also a house in the mountains. “She made me an offer where I stayed in the mountain house and painted for a few months, and she got to keep some of my paintings. It was there that I became interested in studying Chinese characters. So it was just a coincidence, really, that I came back here.”

Taiwan is an island in the western Pacific Ocean that lies about 100 miles off the coast of southeastern China. The population is 23 million. Taipei, the capital in the north end of the island, is the seat of government of the Republic of China (Nationalist China). The People's Republic of China administers mainland China and its administrative regions. Taiwan is viewed as part of China, yet neither officially recognizes each other's sovereignty.

His recent stay in Taiwan had been a long one separated by brief stretches of hopping to Hong Kong or Macau or some place local. After the mountain house exchange, Mark found another opportunity in a small town with a family who own a Vietnamese restaurant. If he helped out they would provide food and lodging. "It's a lot of work," he says, "and pretty much everyday. But when I have a chance, I explore different parts of Taiwan. I also play basketball here almost daily.” Though he has no current companion, his best friend in Taiwan is Xiaofang, the woman who runs the Vietnamese restaurant and with whose family he is integrated. “I do have other friends here,” he says, “but none that I'm particularly close with.”

"Kaohsiung 2.” 2014. “14" x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

“It's been a good situation for me,” he says. “My expenses are very low and I have plenty of time for painting and studying Chinese. I'm mostly just responsible for buying paint. It's certainly cheaper than paying for rent and food in New York, and it's also like going back to school to major in Chinese, but on the cheap.” And he can paint things other than people’s faces. “Painting portraits is stressful. There’s always a sitter who has expectations, has a reaction, will judge it and tell you what he or she thinks at the end. With painting a landscape, it doesn't matter if it's bad or if it's an experiment that doesn't work. So after two years of painting nothing but portraits, it felt very refreshing.”

Recently he sent me a handful of paintings with the title ‘Military Village’; like earlier landscapes and paintings of houses he had sent me a few weeks before, I was struck by the loose vigor of these pictures. In his portraits was the promise of a painting style, but these were paintings of promise in themselves, signalling a new confidence — what Michael Torlen described as “capturing the energy and fluidity of that part of the world." Torlen added that Mark was "a gifted, intense artist whose work should be seen by a large audience. His expressive, spontaneous, fluid paint handling is a reflection not only of his passion for the medium, but also, in my opinion, is an effort to virtually engulf the subject matter into the paint itself. Rather than a painting of, he strives to make a painting that embodies.”

More paintings of the military village were sent to me, some of which were a single setting and vantage point repeated. I was curious what drew him to the subject. His answer explained the challenges he faces in his practice in Taiwan.

FROM THE 'MILITARY VILLAGE SERIES'

"Military Dependents' Village 27.” 2018. 14" x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

"Military Dependents' Village 28.” 2018. 14" x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

"Military Dependents' Village 31.” 2018. 14" x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

"Chaozhou 10.” 2015. 14" x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

“Before I started painting there,” he said, “I’d pick a new spot in town here, set up, paint there, then pack everything up and take it back to the house. Taking public transportation with a painting, easel and painting supplies is very difficult. About three months ago, in a town called Fangliao, about 30 minutes south by train, I asked someone who runs a betel nut stand on the side of the road near a fishing harbor if I could store my painting things behind her stand for a week or so, so I could keep painting at that spot everyday. It was nice for the sake of convenience, to not have to worry about picking a new spot and carrying all of my things there. After that I thought I’d do the same at this abandoned military dependents' village here, leave my things set up there and return to paint every day. What attracted me to this spot was the visual complexity of it, but alos the fact that there were no people, no annoying gawkers watching over my shoulder or trying to have a conversation with me while I'm working.”

His interest in Taiwan's history, especially its colonial vestiges, gave added motivation to explore the village. Originally built by the Japanese, early in the colonial period under their rule (1895-1945), it was later settled by Chinese Nationalists after the Chinese Civil War, which ended in 1950.

“There are a few leftovers from the Chinese Nationalists,” he said, “some stickers on walls, a uniform, a hat, bags, and so on. I read recently about an airport that the Japanese built in 1920 not far from here, and how, after a 1930 incident between some colonial authorities and aborigines in the central mountains, the Japanese flew from that airport to drop gas bombs on the aboriginal communities. There might not be any direct connection between this abandoned village where I'm painting and that airport, or that incident, but I've considered expanding the project and painting in those places. The problem is not having a car here, nor having access to one. I’m limited in my ability to take on new projects like that, which is a big reason why I'm painting the military village. Leaving my things in that building there and getting to paint there daily, it’s very convenient. But also, there’s enough there that I've been able to make a lot of paintings. I've made more than 30 already.”

"Chaozhou 10.” 2015. 14" x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

Like Monet’s haystacks, the military village is a pictorial subject that won’t let go, and though the historical background of such places fills Mark's curiosity, and possibly informs the quality of the paintings, the ability to complete canvases without a lot of fuss is what fuels his progress.

Taiwan suits Mark for the present, partly because it addresses his pennilessness, however this is not the cheapest country to live in. Comparing the 2018 ‘cost of living index plus rent’/‘cost of groceries index’, the US is 56/73; the UK, 55/61; Greece, 38/51: Mexico, 22/32; and Taiwan, 41/79. So yes, he is better off in Taiwan than in his home country, but not better off than in Greece or Mexico — equally attractive countries to paint in. Yet because of the living situation with the Vietnamese family, Taiwan makes sense for now. Plus, with the secondary passion of learning to speak, read and write Chinese, he is in a place where his life is carried on entirely in this language. “The only English that I speak,” he says, “is with Xiaofang's four-year-old daughter, Ke-yuxin. I've been teaching her English for a while.”

"Shoes.” 2018. 14” x 17". Acrylic on bristol paper.

So what does the future hold for this 31-year old? In the coming months he says he just wants to continue what he’s doing, and the only thing he’d change would be to have more money. I'm mindful of the comment of his former teacher, Michael Torlen, who said “If he had the resources — studio space, materials, funds — to paint larger paintings, I think it would provide Mark with the opportunity to give voice to his vision and talent.” Perhaps more than anything what he needs is a patron, or someone who is committed to buying his paintings. "I had brief stretches of that," said Mark, "where I was making portraits for people, or landscapes, like the situation I had with the mountain house in Taichung. And, about five years ago, a commission to make a bunch of portraits of some people who run a wine label in Napa Valley. I thought the situation was kind of stressful, really."

There it is again, the word 'stressful' applied this things worth avoiding: painting portraits on the street; the daily lugging of an easel and materials to a site. Might it imply that the absence of it is what he is looking for? I asked where he would like to be in five years, and if it might be in this part of the world. "It’s hard to answer. I think the interest in different things in Taiwan started to slowly accumulate, and then snowballed. Taiwanese people have a reputation for being really warm and welcoming toward foreigners, and I have definitely experienced that. The people here are great. I wouldn’t mind living here long term, but no, I don't have any long-term plans. I think everywhere is beautiful, but it's just maybe more subtle in some places than others. But also, once you start painting, it's really just shapes and colors."

"All I'd really care to change is having more money, I think. Today I need to buy socks, underwear, paint, a new easel, those kinds of things. Other than that, I'm really pretty happy.” ≈ç

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher/Editor of the Journal of Wild Culture.

Mark Nilsson can be reached here.

Comments

Nice piece like the reportsge

Nice piece! Like the style: reportage vs art criticism.

Whitney,

Whitney, I met Mark around 2011, before the New York Times article and video was made about him. I originally met him when he was painting on Fifth Avenue, along Central Park. On that day he had been displaced because of construction at the MOMA site.

I’ve been in contact with Mark over the years and was one of those ‘patrons’; he came to our apartment to do portraits of my wife and me. Your article truly captures the essence of who he is. His journey is only beginning and I put no limitations on where he will ultimately end up, assuming the opportunities present themselves. I look forward to seeing what the future holds for this talented and intriguing individual.

Best,

Ron

Thank you for writing this…

Thank you for writing this piece on Mark. I met Mark the summer before the NYT found him. In your article you mentioned this time period being tough for the artist. I had no idea. I tried to buy a portrait that he had taped to his table on 53rd st. He told me they weren't for sale. He also offered to paint my portrait for $50. I told him I would buy a dry one for $60 because I couldn't transport a wet piece at that time.

We laughed a bit and Mark understood the situation of not being able to care for a wet portrait properly.

Over the next year or so, Mark painted me, my wife and my mother. We love his style and hope he keeps painting. I would like to help Mark in some way. A plane ticket, some cash, supplies, rent? I don't know what he needs but I would like to help him keep painting.

Again, thank you for updating us on his career and please let me know if there is any way I could be in touch with Mark.

Hi Michael, Nice to hear all…

Hi Michael, Nice to hear all this. Get in touch with me (see contact page) and I can connect you with Mark. Thanks, Whitney

Add new comment