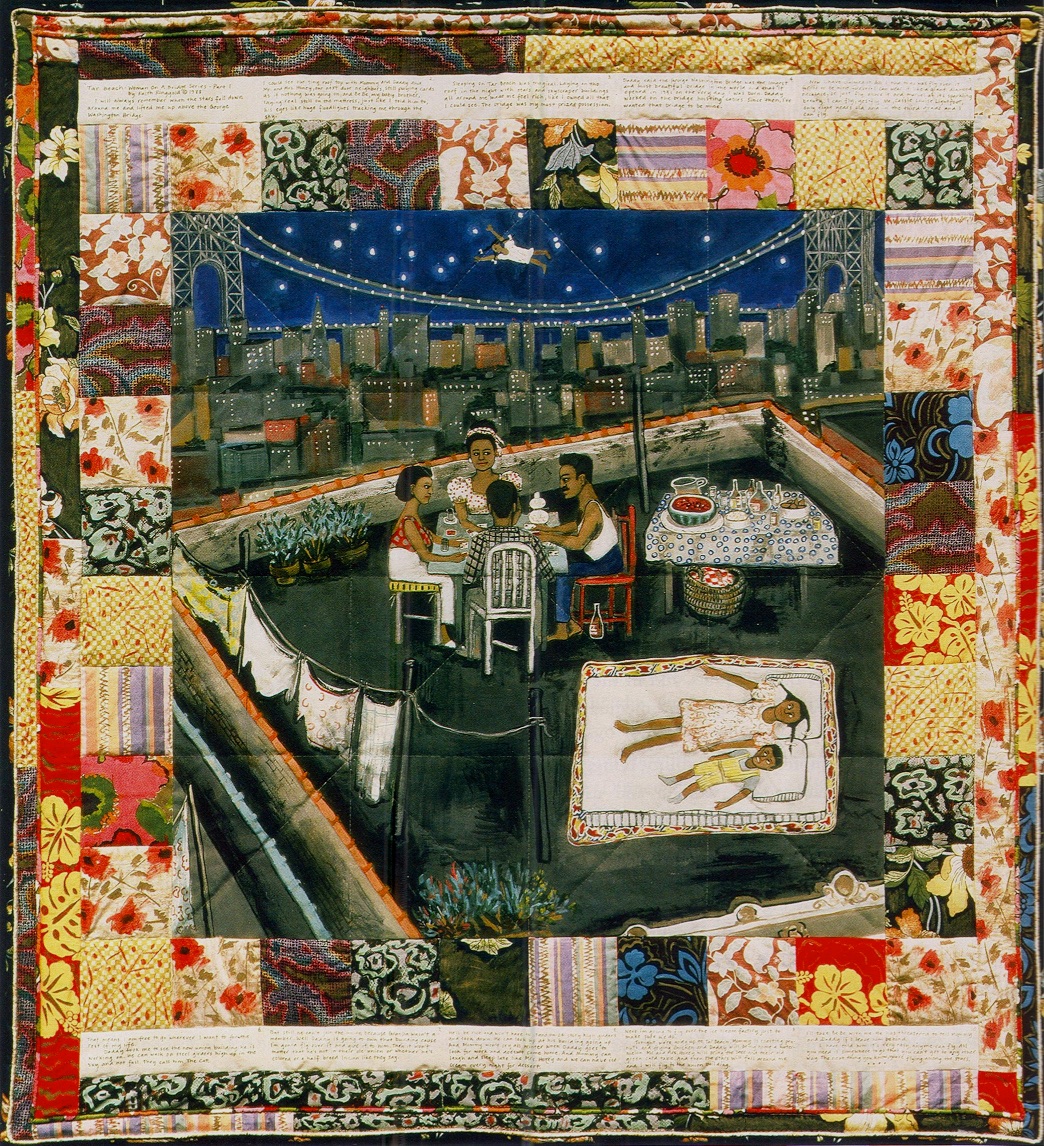

Faith Ringgold, 'Tar Beach', 1988. (detail)

EARLY CONVERSATIONS ABOUT ART. I had a couple of early experiences with artists that made a big impression on me, though at the time I didn’t realize it. I was a latch-key kid in New York, in Flushing in Queens. My father, who was a Rabbi, died when I was eight. You can imagine how awful that was. He was kind of a saint, if you’ll forgive the reference, and it seemed like tens of thousands of people came to his funeral. It was hard for this little girl to believe, and so I gave up on organized religion.

We were five kids and my mother had to work. After school I would go to the library because at that time kids could go to the library and be safe. It was warm and well lit and I could get reference books, and it was in between my home and the school. I would do my homework at those wonderful wooden tables with four chairs on either side. I was about ten or eleven. If you go every day and you meet somebody, you say “Hi”.

You’d look inside and there would a road or a shelf that led to nowhere.

There was a man there every day. He and I would say “Hi.” "Hi." After several weeks we started moving our chairs toward the centre, he and I. He would sit here and I would sit there. We’d say “Hi, how are you?” And we’d also say “What are you reading?” After much conversation back and forth one day, he said, “I’d like you to come to my studio.” I said, “Where is it?” He said, “About three blocks from here.” Now I was Miss Goody Two-Shoes, and I never crossed my mother, never. So I said, “Oh, I couldn’t . . .” And he said, “Why not?” I said, “My mother would be furious! She wouldn’t let me do something like that.” And he said, “Well, you don’t have to tell your mother.” So, being Miss Goody Two-Shoes, this gave me an opportunity not to be. I said, “You’re sure it’s only three blocks?” I was thinking I could run back to safety at the library if there was a problem.

It’s very important that I add that there were no sexual innuendos here. There were none.

And so we went. He lived with his dreadful mother and his disabled brother, and the mother was always screaming, always. His studio was in the one-car garage. There were incredible shelves and cabinets and a work table. It was like Toys’R’Us is today for a kid. I couldn’t believe it! After we were there for a while and I got over how wonderful it was, he showed me this shadow box with a pane of glass and objects inside. “Tell me what you see.” I’d look inside. There would be a bird, a fragment of an astrological chart, a road or a shelf that led to nowhere. I thought, oh, I love this! I started talking and suddenly I was a blathering idiot. That was the day I became an art dealer.

A Joseph Cornell box._

This became a regular event. We’d go from the library once a week or so. He'd showed me things and I’d talk. I was like a sort of tabula rasa who couldn’t give a damn about all the negativity that I hadn’t learned yet from my parents. He really listened. One day I saw this box that was the best one I thought he’d ever made, and I went on and on about it. He said, “I want to give you this box.” Well, I’d already been lying to my mother and so I said, “Oh, no. I couldn’t take it. And he said, “Why?” “My mother!” He said, “We don’t have to tell your mother.” True, we did not have to tell my mother. He was right. But I did not take that box. Years later it went up for auction and sold for a million dollars. This man was Joseph Cornell, a brilliant and now famous American artist — a man who was also known for being very eccentric and very shy and reclusive, living for years in Queens with his mother and brother. So it makes sense that it took he and I months to actually have a conversation. He understood how weird it was to befriend a 11 year old child, who he suspected was smart.

He says, “OK. Just look at the dots. See what your eyes do."

In my era, in the forties and fifties when I was growing up, we didn’t have malls. We didn’t have places where we could meet. So what we did do was take the train into Manhattan and go to museums. I spent a good part of Saturdays and Sundays at the Met or the MoMA.

One day there was a big event at the MoMA where they were unveiling a new abstract painting, a new acquisition. A red rope hung in front of the painting, and long lines of people stretched around the room. I’m looking at the painting and I’m having trouble. I was about 12. I turn to the guy behind me and say, “Boy, I don’t understand this!” And he says, “What is it you don’t understand?” I say, “I don’t know what it’s about . . .” He says, “OK. Just look at the dots. See what your eyes do.” I do everything he says and it starts to work for me. He tells me to watch the colors and see what happens with that. I say, “It’s incredible that you know this! How do you know all this?” He says, “I’m the artist.” I say, “Get out of here!” It was Jackson Pollack.

Joseph Cornell in his garage in Flushing, New York._

AN EYE ON THE MARGINS. In the sixties I was teaching art history and I had a realization — having watching a colleague try to repair his ancient course book with a ruler and some tape — that the curriculum had not changed in years. Also, there might have been one or two women included in Janson’s History of Art, while in MFA programs in general about 60% were women, and none of them ever getting represented. This was the time of Betty Friedan, Bella Abzug and Gloria Steinem, and all of them were part of my life. I’m a little kid next to them, but their ideas were very present. So I went to the chair of my department about my concerns and her response was, “It teaches them to be better mothers and fathers.” I said, “But I’m not teaching early childhood education!” I went to the Dean and he said, “It pays the rent.”

Hung Liu, 'Five Eunuchs', 1995. Oil on canvas, cigar boxes.

My husband, who was a doctor and because of that there was always going to be a roof over my head, said to me, “Why don’t you resign?” Hmmm . . . I never thought of that. So I wrote a letter of resignation listing all my grievances: that none of these kids were going to get a job, that women and people of colour were not included, and that the textbook was just a tome republished every 5 years. In their infinite wisdom they offered me a $5000 raise (a lot of money at the time), which was probably the biggest insult. I quit.

I stayed in our home in Long Island for three weeks and drove my family crazy — waking my sons up at 6 am so I could make their beds, cleaning the grout between the shower tiles with a toothbrush. My husband, a man of few words, said “I didn’t marry you for your hausfrau abilities. I will pay whoever hires you. You have to go to work.”

I got into Manhattan and I walked around my favourite places — the museums and galleries. In time it became clear to me that women were in none of these places. I thought, “How would a woman know what to do if she didn’t have a role model?” I decided instantly that I had to establish a gallery for women and people of color.

Troy Abbott, 'Bernie,' 2013. Digital bird cage sculpture.

When I opened my gallery on 58th St. between Lexington and Second Avenue there was only one woman of color in the whole city of New York, and I had that artist in my gallery. The [New York] Times wrote me up, all the magazines wrote me up. As women’s issues and multiculturalism were becoming the thing, if you were a museum director and you were doing a show and you wanted to include those people there was no way around me — I had the best there was. Of course there was this great void in their collections that my artists were able to fill. So they got to know me, they got to know my artists, and 60% of what I sold I sold to museums. Things were going well so I was able to get a new gallery on 72nd St. and Madison, until my husband said I was paying too much for rent and I bought the space in Soho at 132 Greene St.

DOING IT FOR WHOM? Let’s get something clear here. What I was doing was not wanting to do advocacy in the social sphere or wanting to help. When your father is a rabbi — or a minister or a priest — there are certain forbidden things. You can’t say the ’n’ word. You can’t say kike or wop. I can’t tell you how unacceptable that would have been. In my house it would have been worse than stealing. So there were differences for us. What I’m getting at is I was not doing a social thing. I wasn’t a social worker. I thought it was a good business decision to show the work of these artists who had a lot to share, and when an artist goes deep, people show up.

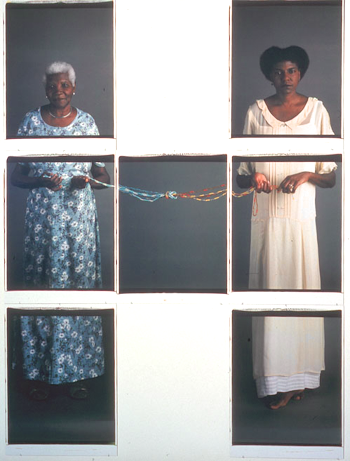

Maria Magdalena Campos Pons, 'Replenishing', 2003. Polaroid.

RESEARCH. When Faith Ringgold first showed me her quilts, I went away and did a lot of research. I learned how when the slaves in the South made the mistress’s quilts out of fine silks and velvets and satins, they also made quilts of their own, out of the flour and sugar sacks, because they wanted to tell their stories. Quilts are not just about bed covers, they’re about many other things too: What to do with an impotent husband, what to do with a child that has a fever of 102˚ because there were no doctors making house calls. Their personal histories on these quilts — a stick figure for Mary and a stick figure for John, and then baby John or Mary in such and such a year — were similar to the history my mother passed down to me orally. All these stories are universal. I saw that in Faith’s quilts, and when I did that research it helped me to appreciate that even more. I was able to relate to what she was doing from my readings and research, and affirm the importance of her work.

For me, art is our link to the past and our gift to the future, and our reportage of what is happening currently. I’m not opposed to political pieces, I’ve shown political pieces, because I think we need a record of our time. Who will be included in my great-great-great grandchildren’s art history books? Who will they be looking at? What will be our contribution to history?

The best thing an artist can do for their career is to go out and talk about the work.

OTHER SIDES OF THE ARTIST. As an art dealer, I know a lot, which sometimes gets in the way, but I have to have a visceral reaction. And, I know this sounds terrible, but I’m also looking for intelligent artists. I want the artist to be able to talk about their work. The whole concept of an artist wearing a beret and working in a cold garret is over. The best thing an artist can do for their career is to go out and talk about the work. I talk a lot about the work a lot, but I can’t always go, so they have to go sometimes and be articulate and steeped in art history. I’m always looking for people who are making such inroads in their media, and who know everything they’re doing when they’re doing it! I don’t show untrained artists, although I love that work and I have some of mine own, but I want artists who are trained.

I don’t bargain with people about the price of the art. The price is worked out very carefully between the dealer and the artist, and a very serious calculation is made. It’s not okay to negotiate. If someone comes to me and says, “But so-and-so gives me 30% off. . .” I say, “Fine, go back to so-and-so.”

Enrique Gomez de Molina, 'Rhinoplasty', 2010. Hybrid taxidermy sculpture using jewel beetle wings, peacock feathers and buffalo horn.

VALUING THE PRACTITIONER. I often find that art professionals don’t like artists. That’s very painful for me. I don’t think you should be doing this unless you really like artists. They’re different than the rest of us, that’s absolutely clear. They need to be — not coddled, that’s the wrong word — they need to be treasured. And they think they need to be treasured.

Artists are always working to make their best piece, and maybe that’s why they live the longest — because they’re still working on making their best piece. If I’m doing a group show and an artist asks me what one piece they should choose for the show, and I say they should choose their best piece. Consistently they say, “But I haven’t done my best piece yet!”

When I’m with my artists we choose to eat and drink together as another way to say we love each other. Food seems to be universal, and they love it when I say, “We’re going to have a party with Japanese food or pizza or Middle Eastern.” I can have 20 people over in a minute. We use a lot of Prosecco. No one gets drunk. Most artists traditionally work in isolation, so how nice it is when we share a meal. One of my artists will bring some special leaves to adorn the table, and someone will say, “I’ll open the wine!” We’re part of a family, but we’re an oddball family, we’re not the Brady Bunch or the Cleavers. And they all like each other because they’re all learning from each other, and they’re all sharing mom. These people are my artists, but they are also my friends, my family, my colleagues, my co-conspirators. What we do is intimate.

Faith Ringgold, 'Tar Beach', 1988. Acrylic on canvas, tie-dyed, pieced fabric border.

Artists and art works displayed in this article are represented by Bernice Steinbaum.

WATCH THE TRAILER OF THE FILM ON BERNICE STEINBAUM.

FESTIVAL SCREENINGS OF BERNICE

Palm Springs International ShortFest (June 16 - 21) — Sunday, June 21 @ 3:30 pm.

Madrid International Film Festival (July 2 - 12) — Thursday, July 9 @ 11:10 am.

Art Basel in December — TBA.

For information on screenings of 'Bernice', visit the site of the filmmaker, Kristina Sorge.

This article first published in The Journal of Wild Culture, June 19, 2015.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher/Editor of The Journal of Wild Culture.

Comments

Awesome piece Whitney. I

Awesome piece, Whitney. I loved it! My eldest daughter is an art dealer in London and I'm sending her this piece. Gotta see the movie, too . . .

A charming, vivid, inspiring

A charming, vivid, inspiring piece.

Add new comment