Drawing by Efrain, 12, El Porvenir, Guatemala. “A man and his son are working cleaning the crops because it is the time of the year to do it. Corn and beans are important food for Guatemalans. What I also represent is the value of planting our food.” [o]

WHITNEY SMITH In terms of the work you’re doing today as a biologist and ecologist, what most concerns you?

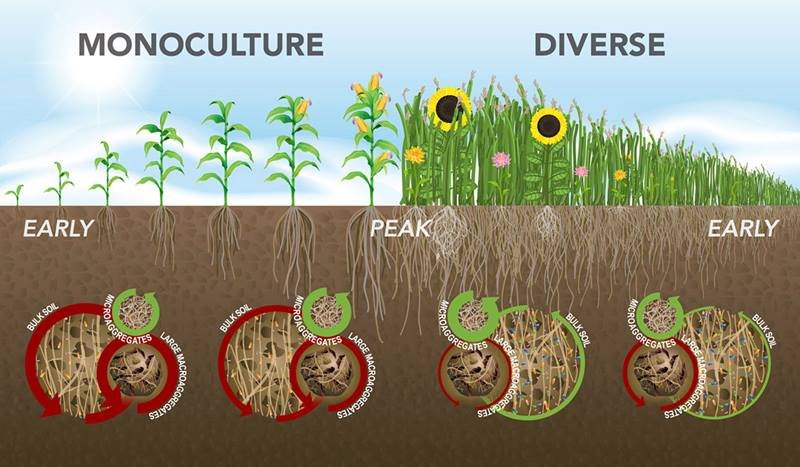

IGNACIO CHAPELA A very important problem today is our failure to fruitfully understand, interact and deal with a fundamental principle of biology: diversity. It's not only the fact that we're losing diversity, but that we're losing it because we lack the imagination and intellectual capacity as a culture to understand and to behave coherently in relation to this principle. High input monoculture farming implies loss of genetic diversity. Why do we need to do that? There are many ways of dealing with food production, agriculture and forests, many ways that do not require monocultures. But it is our way of understanding and approaching biology, approaching life that eventually forces those diverse systems to become less and less diverse, more and more homogeneous, to fit our idea of what is optimal or what is good.

You cannot have sustained collective critical inquiry at the same time as having a hierarchical structure.

What moves biology is diversity, change, fluidity, the fact that nothing is set, and that there are no rules and no laws. The effort of trying to produce something equivalent to Newtonian physics in biology has failed over and over, and yet we stubbornly keep coming back and attempting to impose these laws of nature that don't exist onto nature that is crying back to us about how wrong we are. You see it over and over again in biotechnology. It doesn't deliver on its promises, ever. And yet, we stubbornly continue to expect those laws to rule the biological world, when they don’t.

CHRIS LOWRY Yes, driven by man as homo economicus — that everything is seen through the lens of profit maximization. A person who is part of the dominant paradigm would say biotechnology works well. “Monsanto’s monoculture works very well, thank you very much.”

CHAPELA And makes money.

LOWRY And maximizes yield. And they would say, from their point of view, biotechnology is a success.

CHAPELA I agree with that, except that the economic maxim is a daughter of the problem. It is not the problem, it is simply one of the expressions, one of the descendants of the root problem. And the root problem is, it's a misalignment between the way we understand and the way things are. So yes, Monsanto makes money, which is really the product. They do not necessarily produce more volume. For instance, the productivity of a monoculture in the American Midwest is just terrible, and it's coming to an end. Whereas the productivity of our high diversity field in Oaxaca, in a Milpa system [a traditional intercropping system of regional vegetables], productivity and yield are very high. There are many ways of analyzing this, even with the concepts of econometrics. If you look at yield, and you include the yield not only of the carbohydrates you're pulling out in the form of grain but also the nutrition in vitamins and minerals, if you include health factors as yield, there's just no comparison between an acre of Iowa cornfield and an acre of Oaxaca Milpa. An acre in Iowa is mining that will never be sustainable, whereas an acre in Oaxaca has been producing for 10,000 years and will apparently continue to produce for that long if allowed to do so.

A combination of factors increase microbial diversity. Green arrows indicate higher diversity and red arrows indicate lower diversity with arrow thickness representing the strength of the effect. [o]

SMITH From the beginning of our conversation you’ve said that the loss of diversity is largely through a lack of imagination in our culture. When you talk about imagination, do you mean openness, and the act of opening one’s mind to possibilities we might not be used to?

CHAPELA Yes, I think that is the point, it's openness to the other. In my world as a biologist, which is the world of the living, I need to make a strong distinction between the living and the non-living. The world of the living is so diverse and different that it takes training of the human mind to recognize that there are other ways of being. For example, a rewarding part of the process of becoming a mature biologist is to learn about the incredible diversity of sexual systems and reproductive systems (while acknowledging that sex and reproduction are different subjects). If you look at fish, then look at mammals, then if you look into the world of microbes, whoa! The world is bewildering in its diversity of sexual systems, reproductive systems, and systems of interaction that, on first inspection, we would have interpreted as sex, but then turn out not to be sex. This is a process by which a biologist is trained, through the exploration of living systems, to keep the mind open. In our education systems we seem to be anti-prepared for the world of the living; we seem to be hell-bent on bringing it into bounds and resistant to the possibility of other ways of being and other ways of living.

SMITH So in a sense, to have imagination is to have an image of the other, but also to have an image of how the other sees the world.

CHAPELA Yes, beautiful.

LOWRY And it requires humility. You were referring to, in a way, an all-species perspective in biology, and, as a biologist, you become aware that you want to think that the other is other living things, other creatures, other species, as well as other humans. However, as much as you want to, you can't. As David Ehrenfeld said in The Arrogance of Humanism, the problem with our humanist tradition, coming from back to Plato, is that it's arrogant, anthropocentric and hierarchical. We're on top and we're looking down on everything nonhuman.

Diversity in marine biology . . . How does species richness vary with ecosystem productivity for phytoplankton? The hump-shapes offer a clue. [o]

CHAPELA If you are humble, like you said, and if you have the opportunity to meet the Other, either in your backyard or in the soil, or by travelling the world, this Truth of the Other jumps out and becomes self-evident. I was raised in Mexico and I didn’t go to college in the US, but I’m very interested in questions about education. I remember in the 80s when an education policy in the US removed three subjects from the curriculum of elementary school teaching: biology, geography, and history. These subjects teach you about the other: knowledge about the other living things that are non-human; knowledge about the other that lives in different parts of the world; and the other that has lived in different times in history. That was an incredible moment in the 80s of closing down the focus and saying, hey, now we're really just focusing on us.

SMITH And it was in 1987 that the book The Closing of the American Mind, by Allan Bloom, became a huge bestseller.

CHAPELA Exactly.

SMITH Here’s a scenario I’d like you to consider. You’ve been invited to speak at a conference of elementary school curriculum designers, and you’re there because they want to know more about this question that you have about the lack of understanding and imagination in relation to the subject of diversity. This is a priority for them, and they want to figure their way out of it in the next ten years, it's not a quick project. How might you steer them?

CHAPELA Embracing the openness of diversity is a very scary prospect. It becomes very threatening, very daunting, and there is a huge amount of resistance. I have tried, and I continuously keep trying, on the biology curriculum. To give an example, there is a concept out there called the central dogma. It is the idea that you have a code somewhere that is written up, that has the instructions for how you're going to make things so that their form and their function are pre-encoded in this code. The concept of central dogma is something we all have to accept in order to pass exams, in order to graduate, all the way to the professional geneticists and ecologists who have to contend with it. So, you say to a middle school teacher, “You're going to teach without the central dogma. In fact, you're going to teach against the central dogma.” They're going to say, "Well, how am I going to explain heredity and evolution? Give me something equivalent that is as powerful and as useful that applies throughout all fields in biology, and I’ll go with you.” It reminds me of where I come from, which is from a Catholic background in Mexico. To change the way we teach about biological diversity is similar to the ideological and imaginary castle of Catholicism — a stable institution and frame of mind. The Catholic Church has survived nation states, empires, world wars, whatever you throw at it, partly because it has such beautiful and elegant imagery and makes so much sense — as long as you don't question the fundamental dogmas. We have come to a time in the development of biological practice and teaching that feels and looks very much like religious trappings of something as beautiful and as toxic as the Catholic Church.

On the one hand, this is one kind of science. The other science that also carries that word, as a label, is one that my friend Ian Ball, the historian, defines with four words: sustained, collective, critical inquiry. It is a human activity that is about asking questions, doubting, and doing it collectively. This means we share with people who are alive and people who are dead, sharing our understandings and not giving up on questions. Sustained, collective, critical inquiry. This way of understanding does not lead to a pyramidal hierarchy. It is a more flexible, horizontal and dynamic network of people committed to inquiry. You can see how one is completely opposed to the other. You cannot have sustained collective critical inquiry at the same time as having a hierarchical structure. You cannot have them both. This is the schizophrenic nature of science today, in that ‘science’ is a word behind two different understandings of who we are in the world and what the world is about — and it’s a continuous back and forth between these two ways of understanding.

The monolithic “rule of the laws of nature" mentality wants one answer to solve every problem.

SMITH I want us to go back to this place where you’re about to finish your talk at the conference of curriculum designers, and they're inspired by what you're talking about, but they're confused. They're thinking, okay, I’m on board, but how do I do it? What are you going to leave them with?

CHAPELA I'd leave them with a practice, a practice that requires exercise that, first of all, includes what Chris mentioned: humility. And secondly, a practice that invites curiosity for the world, and openness to accept what the world has to say, instead of imposing what we think the world is supposed to say back to us when we inquire about what it's doing. So, as a first step, the humility is necessary, and it needs to be practiced. We are born arrogant and we are raised arrogant. And so like any muscle, it requires exercise. And then the practice of observing and watching, but watching in order to learn from the other, in order to accept what the other has to say, rather than what I’m expecting the other to tell me.

LOWRY How would you advise them to defend themselves against the dominant paradigm as they go on this path and as they teach others — since it takes a lot of strength to be a nonconformist in any way?

CHAPELA I’m a member of the European Network of Scientists for Social and Environmental Responsibility, ENSSER, and within this organization, this is something we're confronting a lot. The people I talk to within that group are the biologists rather than the physicists, and that is a common understanding we have in ENSSER. And yet we also are in common understanding of how dangerous it is to try and butt heads against a system that is very monolithic and very strong and very powerful. So first of all, I would say, you need to survive as an individual, as a teacher, and in a network.

So networking and supporting is what we do in ENSSER. Making sure, before we come out bashing GMOs, we make sure that we are on the same plane. No going out wild as individuals. Develop networks, survive as an individual, teacher, survive as a network and reproduce – these are fundamental questions of our times. The fundamental motivation of the 20th century was produce, produce, produce! The key questions are biological questions: survival and reproduction.

Ignacio Chapela speaking on a panel about GMOs at an ENSSER conference, 2018, entitled, 'Bound to fail: the flawed scientific foundations of genetic engineering." [o]

SMITH In relation to what you’ve said about the lack of imagination in our culture, if you think ahead 30 years from now, you're an older man looking back, you still have your wits about you, and you heard about it, or read it in a newspaper that something happened that you never thought was possible — what would that be?

CHAPELA I don't want to read about it in the newspaper, I want to see it happening out in the world, at the smallest possible scale. Part of the monolithic “rule of the laws of nature" mentality is that it’s a mentality that wants one answer to solve every problem, whereas I strongly believe in transformation that comes through answers that are small, localized, and time-specific. Detecting the appearance and maintenance of happiness through diversity is something that we are really good at detecting, really good at sensing it when it’s there and not there. When you walk into a field and you see people dealing with a field that is diverse, powerfully rooted in its history, and deep in the physical roots of the soil, that’s where there is an enormous amount of happiness — and it is very local.

SMITH Foraging for the diversity vibe . . .

CHAPELA Exactly. You can feel it when you’re working with these two ingredients: small scale and local time. I believe in that and I have no doubt about it because I see it all the time. However, it’s a struggle I don't think is going to go away in 30 years. ≈ç

IGNACIO CHAPELA is a microbial ecologist and mycologist at the University of California, Berkeley. He is best known for a 2001 paper in Nature on the flow of transgenes into wild maize populations, as an outspoken critic of the University of California's ties to the biotechnology industry, and for his work with natural resources and indigenous rights.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher and Editor of the Journal of Wild Culture. He lives in Toronto.

CHRIS LOWRY is a media producer and singer. Before working for many years in international development and sustainability, he made films on art and music. Chris was part of the original team that created The Journal of Wild Culturein 1986 and served as the magazine’s Senior Editor. He lives in Toronto.

Comments

Amazing piece with Ignacio…

Amazing piece with Ignacio Chapella! So wonderful his definition of science as collective critical inquiry., and so interesting his data about geography and history courses withdrawn from US school curriculum. It made me better understand its people. Thanks for this!

Add new comment