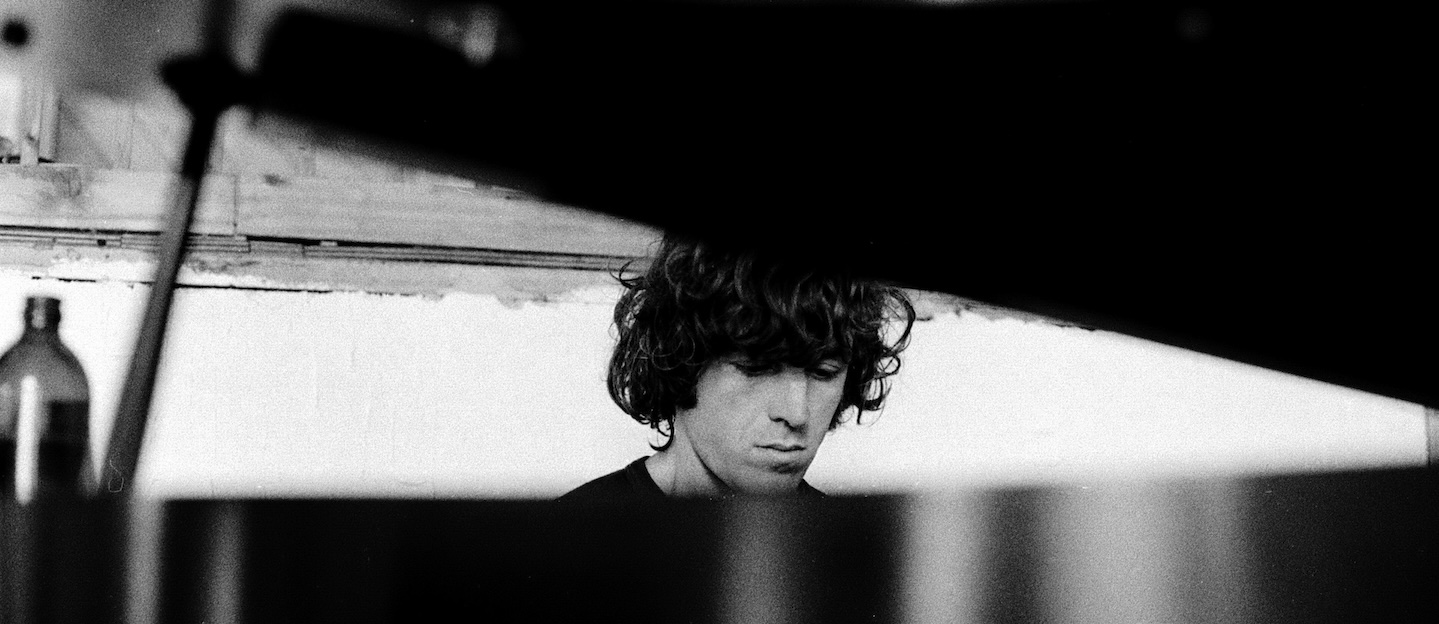

The interviewee at the piano, 1976. [Courtesy of Jim Garrard.)

WHITNEY SMITH Though you were a combat photographer and obviously had that job to do, did you ever become involved in a battle as a soldier where you needed to defend yourself?

BOB NASMITH I shot my gun a few times. I got scared a few times. Not so much in a firefight. Mortars. I hate wars, I hate wars. I can't imagine what it would be like if they had artillery. You're just sitting there. And there's not a fucking thing you can do, and you just hope it doesn't land on you. In a firefight, you got a little bit of mobility. And if you want to, you can just keep your head down and not do a fucking thing. I got to fly a lot. I got an air medal for flying 30 hours of combat, flying into an LZ and flying out of an LZ, a landing zone. There are guys who had air medals with 30 oak leaf clusters for doing long hours of combat. I mean, I see all these movies and there are certain things in all the movies that, that really strike me strongly. I think it was **Platoon, they call in an artillery strike on their own position. This is hair raising, it's one of my nightmares, one of my very few nightmares. I don't have nightmares all that much but one that I do have is artillery, short rounds and being overrun.

On your best days you're living in a tent with hot food, and in your worst days you're humping through the mud going to god-knows-where, having no sense of your goal for the most part.

BARRY STEVENS Did you feel protected by the camera, as though you were an observer of something?

BOB No, I was always aware of putting something between myself and them. I wouldn't do a Tim Page and just click-click-click and go out there and crawl out there and go click. I would not. I would stay low to the ground, or behind the felled tree, or behind the corner of something, and shoot out from there. And then take cover and then shoot out from there. And I would often shoot backwards so that I'm out in front. I don't mind being out front because I've got a bunch of guys 10-20 feet behind me and around me. But I found some of the wonderful shots that you could get would be shooting back at your own guys. That's where the great shots were. 'Cause you're never gonna get a shot of the VC shooting at you.

BARRY Was there anything at all you enjoyed about it?

BOB The experience. I think the experience was extremely important to me. I think it was probably life-changing. You know, as I had mentioned before, I was always a pretty bright little guy and got a lot of mileage out of that. Perhaps too eager to please. Certainly not critical enough and easily led. And I think that changed. But then you saw some disturbing things obviously. There's some awful things. All the nasty little things, a little bout of what I think was malaria, they never told me, but I haven't been able to donate blood. I don't think I had a biopsy, but generally speaking, if you've had malaria, you're not allowed to donate blood. And I had ringworm, and that's nasty.

WHITNEY Did everyone get that?

BOB No. I know I had an unfortunate nickname for a period of time. I was called Scody, and Scody was slang for a really dirty person. I hated showers. I hate cold showers. All cold showers. Sometimes I would get a bucket, hang it up, warm it up a little bit.

WHITNEY In your time there, did you lose friends, fellow soldiers who were close to you?

BOB I never lost a best friend, but I had a couple of guys I knew blown away. Here's one for you. We had a mess sergeant who was a real prick. He was a power tripping prick bastard, and he would really make your KP duty just awful. We went out once, we came back, we found out that the mess and he had been murdered, he'd been killed, and we laughed our fucking asses off. Black humour.

On the ground in Vietnam with fellow soldiers of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, 1965, at the time Nasmith arrived. [o]

BARRY Do you know anything about fragging?

BOB Good question. I was never a party to it having happened. Fragging would be where you had in most cases an unpopular NCO or officer, and it was agreed that they were so incompetent that they were endangering your lives or your friend's lives, so you would arrange for a random shot to take them out, or for a grenade to be thrown at them with an eye to killing them and eliminating them without, to pay the consequences for murder.

WHITNEY That the circumstances lead to terrible things happening, for survival, or for some sort of covert revenge, would you say?

BOB Well, what we also learned, and this is not rocket science, some people don't realize that when they look at atrocities and the terrible things that people do, and those people do terrible, terrible things that are very often around somebody getting killed or a bunch of guys getting killed.

WHITNEY Collateral damage.

BOB The brothers get their blood up, and they get their blood up real strong and they say, fuck you, and they go into a village and they just kill people they shouldn't be killing.

WHITNEY Were you ever a witness to that kind of thing?

BOB No, I never saw that. I never saw that. We were still a pretty good unit by the time I was there. But I know it went on, I heard that it went on, never when I’d been around. It's a dirty, dirty, unpleasant, uncomfortable way to live. It's tough to be in the infantry in terrain like that with weather like that. On your best days you're living in a tent with hot food, and in your worst days you're humping through the mud going to god-knows-where, having no sense of your goal for the most part. It's a hard life and it makes you hard. And it makes you hard in a lot of ways — spiritually, ethically, morally. Just in terms of your day to day conduct and how you feel about things. The damage and pain we caused to civilians, the damage and pain that you would see in the faces, in the eyes of innocent people. The people who were caught up in it who could do nothing about it, they were just caught up in it, and it would always make me very, very sad. Very, very unhappy. It's tough to be in the infantry.

WHITNEY Clearly this psychologically disturbing, on many levels. How are you able to cope?

BOB You get time off. You get time off and recharge and then you go back. One of the best parts of being the combat photographer was that I could go into the field, and then if I thought I had enough stuff, after the wounded or whatever had been carried out on the helicopters, the other helicopters would come in with the food or taking equipment out, or whatever. So I could fly back to Tan Son Nhut in Saigon, outside of Saigon, where the labs were, drop off my negatives, and now I’ve got time on my hands. I knew a whole bunch of guys downtown or staying in the fancy hotels; if they're not out in the field, they're going to be at the hotels or in some of the bars. So I go down and set up with them for a day or so, and then go out and get laid, mostly sucked off. I found that that was the best way to do it.

The 173rd Airborne Brigade “Sky Soldiers” were the first major ground unit of the U.S. Army sent to Vietnam. This photograph from 1965 was around the time Nasmith was serving with the 173rd. [o]

WHITNEY And this is sex you're paying for.

BOB Oh, yeah. There's no romance. It’s all paid.

WHITNEY All commercial.

BOB Oh, yeah. But it served.

WHITNEY Can you tell us about the culture of that, taking part in that kind of prostitution?

BOB I think the culture is the culture of prostitution of any war. It's a living and you're supporting people. Also, the VC had a really useful intelligence network through hookers, not surprisingly. They could find out who was in town and from where, what they'd been doing, da, da, da. I suspect it was absolutely no different than any occupied country anywhere in the world at any time.

WHITNEY Would I be right in assuming that the economics of that culture involves exploiting inappropriately young girls.

BOB Often. No, I remember one guy, he said, you know, these Vietnamese chicks, it's amazing. They have no hair on their pussy. And I said, you fuckhead, you've been screwing children.

WHITNEY But you saw examples of what you just described, the effects of horror close by?

BOB I saw guys get pretty cold. Mostly we just kind of got through it and looked forward, you could hardly wait until your tour was over. But irony of ironies, I was pretty well connected. I was going to volunteer and did volunteer to stay longer, because I wanted to get discharged over there. I had a job offer from Life, which was still in existence at that time.

WHITNEY So you were motivated to stay longer, and take that risk?

BOB That was my goal. Then one day, we were flying out, we were the first ones to fly out, and we took some small arms fire from the ground as soon as we got over the trees and we went down into the trees. We got banged up. The crew chief probably broke his back. I got banged up a bit, all the other guys got banged up a little bit. And I thought, fuck this, I could get killed over here. So I took a trip back to the States, and that was kind of fun. And actually, I landed, I guess, probably in Oakland, grabbed an army flight down to LA where my mother and my sister had a lovely little apartment in Arcadia, right across from Santa Anita racetrack. And the last they had heard is that I had been hurt. So I went to their motel, and a guy let me in, it was Sunday, they were at a church. So when they came back in, there I was sleeping on the couch. So it was a wonderful reunion. It was quite a fabulous reunion. So it was very nice, it was a very fun memory of that. I took a little bit of time off and then I was reassigned to the 82nd Airborne, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and that's where I was discharged later on, Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

When I regained consciousness I was sober enough to realize the meaning of the piece of paper on the side table beside the bed . . .

WHITNEY What was it like to return civilian life?

BOB This will tell you. I get discharged and I've got money. I'm wearing my uniform because you can fly for nothing when you're in uniform. I fly into Toronto, it's the end of August, I come downtown to the old Ford hotel. There's a huge writers convention or something, everything is booked up. I get on the phone in the lobby, and there’s a woman there and she says, I’ve had a little luck, I found a place down on the Lakeshore. They got other places there, you want to come down with me. I said, sure. So we went down, and the upshot was, we didn't need two rooms. We did the X, we did some other things. She was a legal secretary from Cleveland who evidently had a thing for uniforms. We drove down to Cleveland and on the way — this is how cold I am, I’m a cold motherfucker — we stopped in St. Catharine's. I introduced her to my father who I had not seen for years, and my brother. We're living in St. Catharine's, and say, well, nice to see you, Dad, nice to see you, John, we're just heading off to Cleveland now. We head down to Cleveland. When I regained consciousness, three days later in the motel, I was sober enough to realize the piece of paper on the side table beside the bed was a wedding license, and that 36 hours of the 48-hour blood test for the marriage license has expired, and I think, what the fuck is going on here, I’m out of here.

WHITNEY And you'd been together for . . .

BOB . . . three days. We're going to get married. I didn't know her. So I headed back to St. Catharine's and left Pauline almost waiting at the altar.

WHITNEY Might you have been doing her a favour?

BOB Huge favour. Huge favour. Lovely little Polish girl. I went back to St. Catherines, lived at home for a while, went back to university.

Bob Nasmith, a couple of years after his return from Vietnam, and in his final days. Photos courtesy of Jim Garrard.

WHITNEY You lived through a remarkable period in your life where you weren’t just flirting with danger, you were wanting to dance with it, full on, until you didn’t. What I know of you is that you are not a hard person. You are actually a kind and sensitive, no-bullshit person. Is there anything you can think of from that experience that brought into your life when you returned?

BOB I’m not sure. Well, one thing comes to mind. Maybe this is some kind of answer. I was doing a photo essay up in the Central Highlands on mobile army surgical hospitals, and it was pretty fascinating stuff. And I spoke some French, and a lot of the people up in that amazing area, since they've been under the rule of French colonials, spoke a sort of French. So I could communicate with some of these people, which was rather exciting. Every once in a while the shit would hit the fan, and they would need extra help. So I remember on one occasion, I was putting down my camera, putting on rubber gloves and a mask, and actually helping a medic, because the doctors were busy with the seriously important stuff, probing and pulling out shrapnel from buttocks and thighs and flesh areas. So I got in there and was actually helping with a scalpel and tweezers. Wind whipping through the tents, dust rising, boy. How that came to serve me later on was in ‘67-'68, I was the assistant medical photographer at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, and one of the reasons I got the job is that I had photography experience, and specifically, I had worked in medical situations as a photographer. Anyway, so there's that.

WHITNEY Bob Nasmith always lands on his feet.

BOB You bet. ō

READ PART 1 and PART 2 OF THIS 3-PART SERIES.

A reader comments . . .

Bob Connor, who served in the security forces at Bien Hoa Air Base at the time when Bob Nasmith was also there, sent us a comment after reading the first interview in this series (October 22, 2022). Here is his comment.

Combat Photos in Vietnam. Bob, I saw your photo taken at Kontum Base (2/68). Since 10/2016, when I started to help in Vietnam through a humanitarian project, I found the mass graves from our war. The sole benefactors are the affected families, which started with me locating one grave of 150 KIA [been killed in action, ed.] at Bien Hoa Air Base (Tet’68). At this base alone is now six with a possible seventh, totally over 1300 KIA. We were attacked by 2500 VC, mostly off our east perimeter.

Today I have a team of 8 volunteers (one security policeman; one cobra pilot, two Army Infantrymen, one Marine Rét.), including a CMSGT Gunnery Sgt, two younger Vietnamese engineers, and one former Vietnamese child civilian (1975), who us now a retired American executive of an American International Corp. Your photos may help in finding the graves from ’68 to the larger battle in ’72.

Can you help? These families endure the same pain as our own. With the help of our veterans who fought these battles we have located the graves of over 8,000 of their KIA. We are also authorized to seek out our own MIAs [missing in action, *ed.]. To date we have provided details of five to the DPAA [Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, run by the Department of Defence out of Offutt Air Force Base and Pearl Harbour.] Our searches include Laos and Cambodia as well. You would be surprised how emotionally one photo could impact over 1,000 living Family members. We do not seek nor receive any funding for our work.

Thank you,

Bob Connor

SSGT 3rd Security Police Sqd.,

Bien Hoa Air Base 4/67-4/68

Interview with Bob Connor

In 1968, 85,000 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam soldiers launched a sneak attack against the forces of the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam, the United States Armed Forces and their allies. This was the Tet Offensive, a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. Bob Connor, who was a sergeant with the Security Forces at Bien Hoa Air Base, explains the attack on the Bien Hoa Air Base in January 31. 1968.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher and Editor and founder of the Journal of Wild Culture. As a musician he performed in several productions that featured Bob as an actor.

BARRY STEVENS is a documentary filmmaker and writer. He was an editor of Peace Magazine and a member of Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament; his documentaries include Offspring (Emmy nominated), Prosecutor, and the multiple award-winning series War Story, stories of Canada's military participation in war. Parts of this interview were taken from conversations with Nasmith for that series. Barry Stevens lives in Toronto.

Add new comment