[o]

THIS SIDE OF DARK WATER

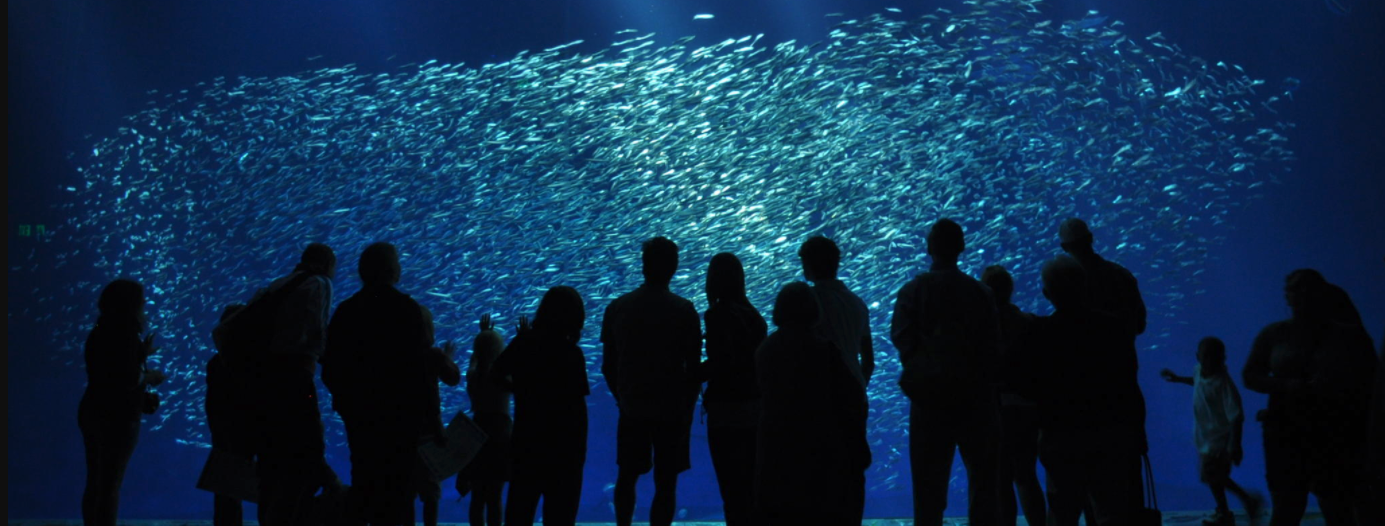

biofluorescent fish keep reappearing

in spinal shine, erotic aural,

goby, sole, and triplefin blennie

currenting like intimate thoughts

toward a wall of aquarium glass & blue light,

expressions distant as the deepest

hadal depth, pheromones

intoxicating more than blackness.

There’s a couple entranced

at the glass, man behind a woman,

her pale, lucent skin

guiding his attention to

a pearled nape to be kissed,

salt in blood remembering

the rise & swell from a sea eons ago

until her hands become two starfish splayed

upon memory as he awakens sun struck,

not all of the dream quite reaching

the morning’s gleamed surface,

coral polished fingernails

still clinging to some reef inside him.

[o]

FAITH FOUND IN A PASTURE

Sometimes it seems God could be

the eye of a horse that holds

a darkened lake, some boat of light

upon wind swept grain. And here

among the opened white scroll

of clouds trapped inside a water trough

lies a baptism without some doctrine.

The mind does not mind the gentle way

one mare disturbs her own reflection,

nudges the still sky into a summer

thirst of ripples. She drinks this

moment from its day, unaware of words

like chalice, sacrament, communion,

or even the soft, repeated recitations

of Eucharist, her only concern,

the forgiveness found

in noon shade, a welcomed grove

where she could return to dream

of an open sky above clover,

a field where there is no man

to follow to some empty stall.

Just beyond the shadow-edged

stand of walnuts and oaks, a breve

of wind hints of another world.

Leaves whisper litanies

while the suddenly restless mare

is eased along her caudal sway,

currycomb of sunshine

unknotting doubt

ray by sacred ray.

[o]

AUTUMN SAUDADE

Tonight the geese gather

in stalkless fields. They shine

like a harvest of ghosts,

speaking of loneliness

as if they had invented it.

A girl in only her slip

answers their haunt of hissing

with kisses.

Yet I imagine another

mouth, perfect for the man

who would become my father,

who brought my mother plums

just to watch her eat them.

She wanted to grow pink

orchards of Satsumas, leave

the paint, the factory, the dingy snow,

and move west to California

where summers wait

like old men on benches.

But now it’s late fall

of later falls, and I am parked

on a hidden edge of the refuge,

cradled in the dark, this moment

undressed for memory, while

longing settles like these sad birds,

becomes something more than

a lover’s soft offering, brief

touch of shadowed down,

something from long, long ago

like an infant’s once suckling

toward sweet, sweet nothing.

THE WILD CULTURE SCRIBBLER'S QUESTIONNAIRE

by Greg Sellers

What is your first memory and what does it tell you about your life at that time and your life at this time?

My first recollection — waking up in my father’s pickup truck late at night as we traveled through an unfamiliar small town during the Christmas holidays. We were some place between Louisiana and Missouri, most likely Arkansas. I was two or three at the time. Christmas lights, strung across utility wires, had interrupted the darkness of my sleep. Country music played softly on the radio, occasionally fading in and out. I remember sitting up and seeing snow flurrying in the beams of the headlights as we approached the town square. And there on the lawn of either a church or the courthouse was what I now know to be a manger of lit, life-size figurines, their glow casting a surreal aura upon the nativity scene. Of course, I was too young at the time to understand what the manger represented, but I sensed it was something mysterious and of great importance. And although I was raised going to church and at times have even felt close to some “omnipotent” presence, I’ve never been able to completely lift a veil between me and unquestionable faith. It is as if that aura I had witnessed as a small boy continues to haunt me.

Can you name a handful of artists in your field, or other fields, who have influenced you and who come to mind immediately?

Poetry influences include Charles Wright, Robert Penn Warren, Dave Smith, James Dickey, Larry Levis, Richard Hugo, Denis Johnson, Jack Gilbert, Michael Burkard, Wallace Stevens, John Burnside, Theodore Roethke, Gregory Orr, Richard Jackson, Mary Oliver, W.S. Merwin, John Koethe, Ellen Bryant Voigt, Anne Michaels, and Lynn Emanuel. Photographers Sally Mann, Clarence John Laughlin, Olive Cotton, and filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky are also important influences.

Where did you grow up, and did that place and your experience of it help form your sense about place and the environment in general?

My father worked on rivers much of his life, thirty-plus years as a tugboat pilot and captain. Because of his occupation, we lived near the Mississippi, Red, and Tennessee Rivers, with most of my childhood and teenage years spent in Sikeston, Missouri, and Decatur, Alabama. Also, my grandfathers and greatgrandfathers were cotton and soybean farmers. Quite naturally, I’ve always felt a close kinship to rivers of the Lower Mississippi and the rural landscapes of Southeast Missouri and North Alabama. Even as an adult, I have found myself living along the Mississippi River in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. My love for rivers and rural settings have definitely shaped my environmental views when it comes to the topics of river protection acts and urban sprawl.

If you were going away on a very long journey and you could only take four books — one poetry, one fiction, one non-fiction, one literary criticism — what would they be?

The Collected Poems of Robert Penn Warren (ed., John Burt), Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man (James Joyce), Landmarks (Robert Macfarlane), and Claims for Poetry (ed., Donald Hall).

What was your most keen interest between the ages of 10 and 12?

Baseball.

At what point did you discover your ability with poetry?

In my teens, I attempted to write lyrics inspired by the music of Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Don McLean, John Fogerty, Jimi Hendrix, and Cream. At that point, I also began penning love poems for my brothers to give to their girlfriends. To be told that my lines had elicited a kiss or a tear spurred my early poetic endeavors. Years later, I began to take poetry writing more seriously when I enrolled in an undergraduate poetry writing workshop to satisfy a degree requirement. It was under the mentorships of poets Kate Daniels, Rodger Kamenetz, and Dave Smith that I decided to pursue a MFA in Creative Writing.

Do you have an ‘engine’ that drives your artistic practice, and if so, can you comment on it?

There’s an inner voice that speaks to me, that will “echo” a certain phrase or line until I decide to write it down, thus creating a starting point for the next word, phrase, or line to occur. The process continues by “letting the line lead the way,” by allowing the next word or line to derive from some sonic device or mental image triggered by the previous line. Should this process stall for an extended period, I then find myself taking a drive in the country to reconnect with the inner voice, to “jumpstart” the engine, so to speak.

If you were to meet a person who seriously wants to do work in your field — someone who admires and resonates with the type of work you do, and they clearly have real talent — and they asked you for some general advice, what would that be?

Find a “day” job that will not adversely affect your writing time when you are off. In other words, find a job that will not leave you mentally or physically drained by shift’s end, and one that does not demand you to do additional work during your “off” time. I would also encourage one to read, read, read both poetry and fiction. Pay attention to those lines that grab your attention or that leave a lasting impression. Attempt to understand why those lines are so meaningful to you. Then take what you have learned and apply it to your own writing craft.

Do you have a current question or preoccupation that you could share with us?

I admit the subject of memory has become a preoccupation for me, particularly in its relationships to landscape and writing. Over the past seven years I have gathered over 3,600 quotations and journal entries regarding these. I closely identify with Kazuo Ishiguro’s words from a past interview, “Memory is quite central for me. Part of it is that I like the actual texture of writing through memory. . . . More fundamentally, I'm interested in memory because it's a filter through which we see our lives.”

I often wonder what happens to an individual’s memories when he or she dies. Ever since I was a child, my real fear of death has not been death, itself, but rather what that inevitable event will ultimately “take” from me. The idea of having my mind erased of all things that I hold dear in this life is such an unbearable thought to accept; in fact, it is one I refuse to believe. The Argentinian poet Antonio Porchia wrote, “Memory is a bit of eternity,” and the possibility found in this line continues to give me hope that we will carry such moments into whatever afterlife awaits us; perhaps the memories one keeps are as important as what one believes. With this in mind, I’ve found my “latter” self being more observant of those things around me, which, in my view, is good practice for a poet or writer.

What does the term ‘wild culture’ mean to you?

My thoughts of “wild culture” extend beyond Edward B. Tylor’s classic definition: “Culture, or civilization, taken its broad, ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” I think of cultural elements that are not bound by constraints and do not conform to expected ideals or notions. Imagination is one such element that comes to mind. Although traditional aspects of culture may attempt to curb one’s imagination, they never totally succeed. There always remains some untamed spirit within one’s imagination that reaches for spaces beyond established cultural boundaries. Yet, for some individuals, traditional cultural elements may not be limits but rather inspiration for one’s imagination. I suppose it comes down to what the “complex whole” of culture means to each self. In either case, the imagination remains free to do as it pleases. It’s those unbridled elements of “wild culture” that help to keep traditional cultures from remaining rigid, inflexible, or static.

If you would like to ask yourself a final question, what would it be?

Is there such a thing as a “true” poem?

GREG SELLERS' poems have appeared in Interdisciplinary Humanities, New Letters, Poetry, Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality, Zócalo Public Square, and elsewhere. As the recipient of a Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship and Mississippi Literary Arts Fellowship, Sellers is the administrative librarian at Hinds Community College in Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he lives with his family and survives the summer onslaught of kudzu. Sellers also has a blog, Memory’s Landscape.

This article first appeared in The Journal of Wild Culture, November 4, 2017.

Comments

Here’s an American poet whose

Here’s an American poet whose work is infused with what the Welsh call 'hiraeth': delivering beauty and pain minus sentimentality in one handful.

Add new comment