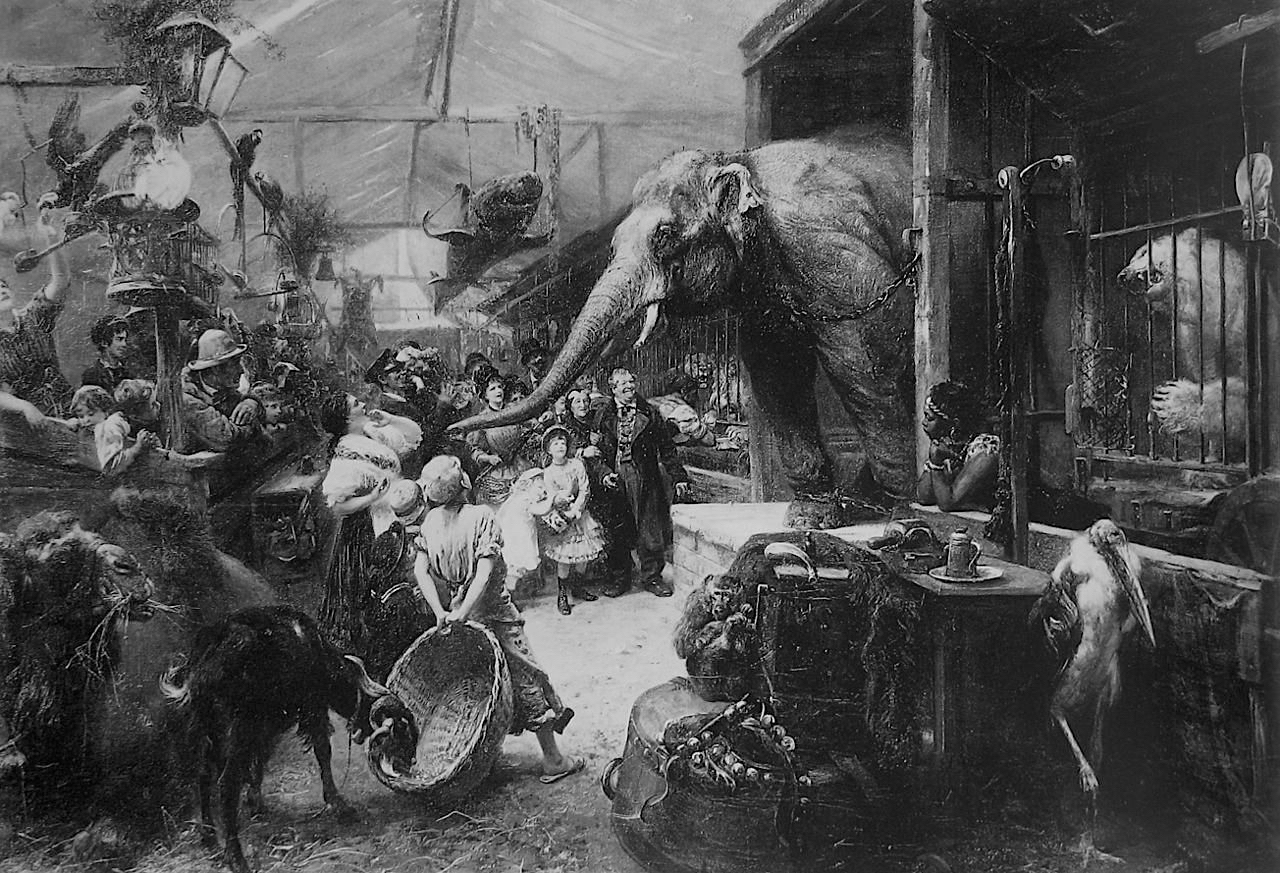

Polito’s Royal Menagerie at the Exeter ’Change in London, 1812. A collection of exotic animals owned by Stephen Polito, a touring showman in Georgian England of Italian descent who had come from his own country to find fortune in London and the provinces. The artist Edwin Landseer came here to study and paint polar bears “true to life.” [Courtesy of E. K. Duncan.]

FAIRBANKS, ALASKA — In the western hemisphere, polar bears have lived in our midst since the Middle Ages — a result of our fascination with these charismatic carnivores. Already in 1252, Henry III of England kept a muzzled and chained polar bear that was allowed to catch fish and frolic about in the Thames. The first unequivocally identifiable polar bears came to Europe by way of Greenlandic Norse traders, and from Iceland, where sea currents still sometimes maroon them. Viking entrepreneurs distributed them to royalty throughout Europe, who kept them in ostentatious menageries or passed them on as gifts to grease diplomatic gears and careers.

Print after Paul Meyerheim’s painting from 1885 of a Tierbude, a German traveling menagerie, a hybrid of circus and zoo. Such “shows” sometimes included taxidermy exhibits. The polar bear in the wagon on the right appears to be rather stressed by its confinement. [Wikimedia Commons]

Polar bear house at the Bristol Zoo, circa 1910. Founded in 1835, the Bristol Zoo and England Zoological Society set out to facilitate “the observation of habits, form and structure of the animal kingdom, as well as affording rational amusement and recreation to the visitors of the neighbourhood.” [Courtesy of Bristol Zoo.]

At the turn of the eighteenth century, new developments in science and philosophy, a burgeoning middle class, and expeditions to the Americas, Asia, and Africa brought about change. Animal collections in Europe — until then largely a privilege of nobility — increasingly welcomed the public. In medieval wildlife collections or "menageries" (such as the one in the Tower of London), polar bears drew a good deal of attention. Beginning in 1693, the first King of Prussia, Frederick I, kept a polar bear and other large mammals for public amusement in a baroque-style hunting enclosure inspired by Roman arenas. These animals were too valuable and difficult to obtain to be killed, but, defanged and de-clawed, they were pitted against each other in faux fights.

He bragged he was doing more to familiarize the masses with the denizens of the forest than all the books of natural history.

In England, entertainers had been displaying all sorts of animals at carnivals and fairs since medieval times. The traveling menagerie, which derived from the processions of Europe’s ambulatory monarchs and their entourages, first took to the roads at the turn of the eighteenth century. In a bid for respectability, the owner of one bragged he was doing “more to familiarize the minds of the masses of our people with the denizens of the forest than all the books of natural history ever printed.”

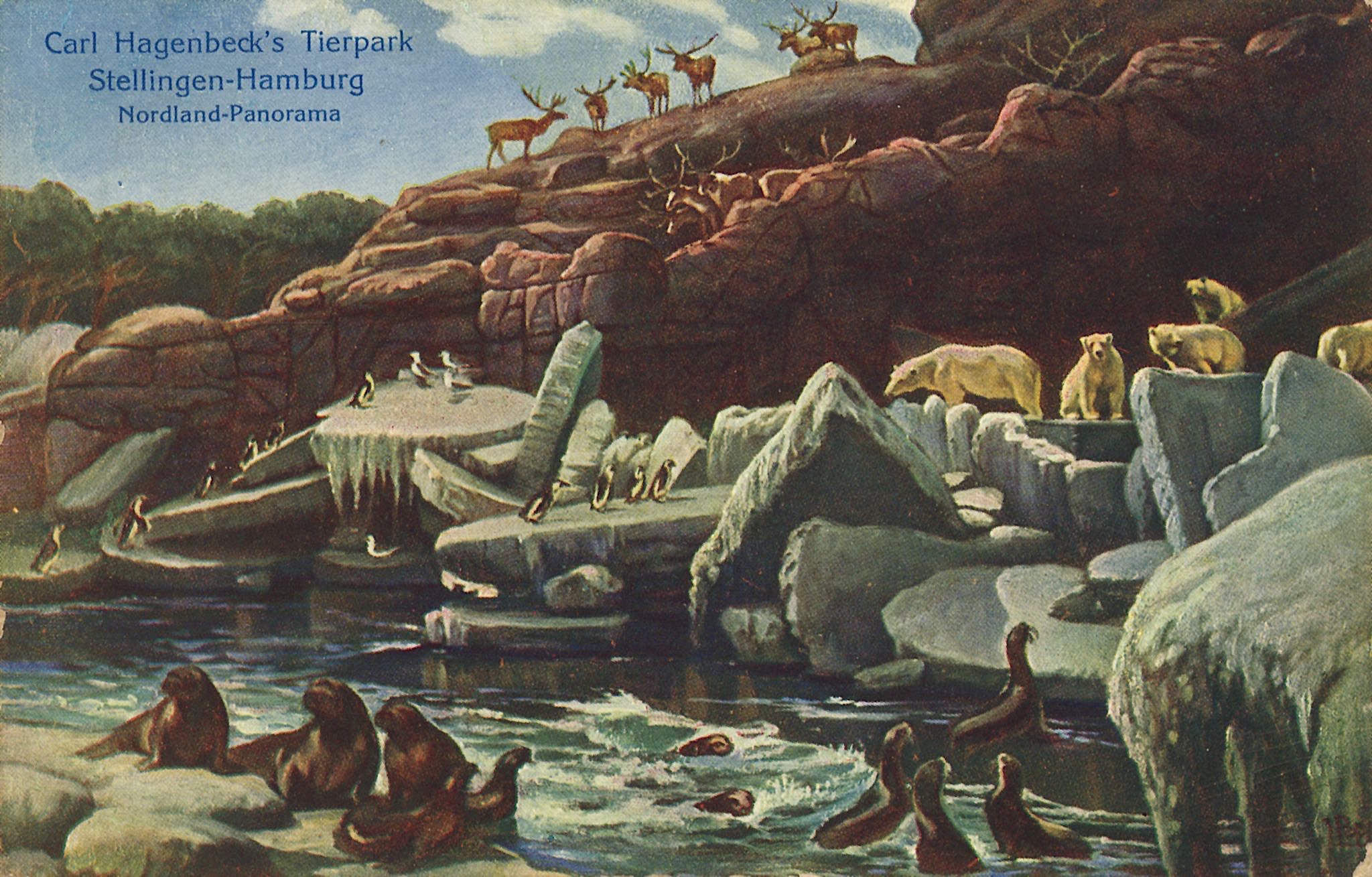

The German showman and animal trader Carl Hagenbeck revolutionized wildlife displays with more natural-looking settings. In his unfenced “Northland Panorama” at the Stellingen-Hamburg Tierpark—shown here in 1910—species seemed to coexist harmoniously, but were separated by moats invisible to visitors. [Postcard; author’s collection].

In 1933, the purpose-designed polar bear enclosure of Munich’s Hellabrunn zoo comprised a semi-circular curved swimming pool and a wide platform with rising terraces. The back wall, which had openings leading to the polar bears’ night quarters, was covered with artificial rock to replicate the Arctic environment. [Courtesy of Tierpark Hellabrunn]

Nobody contributed more to the popularity of captive polar bears, or the look of the modern zoo, than Carl Hagenbeck. In 1848, Carl Hagenbeck Sr., a Hamburg fishmonger, exhibited six seals he’d received as bycatch from fishermen before selling them at a handsome profit. At age fifteen, his son, Carl Hagenbeck Jr., took over what would become Europe’s most famous animal-trade business. He soon supplied zoos, menageries, and wealthy individuals, including the Kaiser; by his early twenties he ranked among Europe’s top dealers in 'exotics'. With a nose for opportunity, Hagenbeck branched out into the budding entertainment industry, mounting “ethnological” and large carnivore shows, as well as a circus.

From their very beginning as cultural institutions, zoos have tried to balance entertainment and education. Today, with climate change and habitat loss from development, thereby threatening the polar bear’s natural habitat, many have added conservation to their mission, including captive breeding programs and scientific research.

Sadly, unhealthy and dreary polar bear enclosures such as this still exist. Chile’s only polar bear “Taco” died in 2015 at the age of 18 at the National Zoo in Santiago. For years, activists protested its captivity in the capital, sometimes with blockades and burning barricades. [Photo by Aldo Fontana]

Zoo design has come a long way, as is obvious from this truly immersive experience at the Detroit Zoo. Modern zoos seek to give visitors an understanding of the bear in its home environment, while also considering the animals’ well being. [Photo by Lon Horwedel.]

I firmly believe there are landscapes that speak to certain individuals more than others do, even to the extent where only one place ever makes a perfect match for such a person. A first exposure to this kind of “soulscape” feels like a homecoming. Fortunately, I have found not one, but two: the Grand Canyon and Arctic Alaska. Unfortunately, lying 2,500 miles apart, they have sentenced me to a lifetime of wandering. I still consider myself lucky, as a wilderness guide of twenty-five years, to have spent my best days in these two magnificent regions. Like the canyon’s, the Arctic’s bare look is deceptive. It too is truly a place where life begins. Beyond keeping polar bears alive through captive breeding in zoos, we must safeguard their wild northern homelands. ≈©

The author, second from the right, guiding a rafting trip on the Canning River in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo by Rich Wilkins.)

MICHAEL ENGELHARD is the author of the essay collection, American Wild: Explorations from the Grand Canyon to the Arctic Ocean, and Ice Bear: The Cultural History of an Arctic Icon. He lives in Fairbanks, Alaska and works as a wilderness guide in the Arctic.

Add new comment