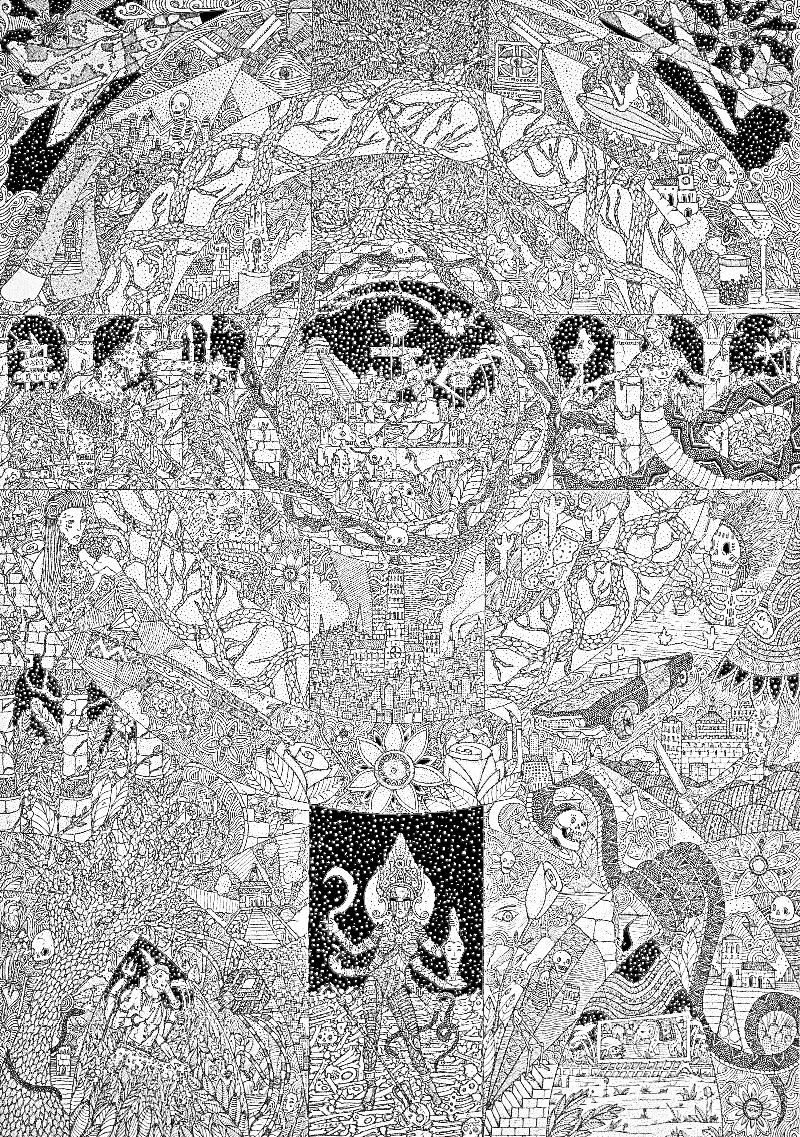

'Ometeotl weeps for Kali in the mescaline dreams of night', by Finn Lafcadio O'Hanlon, 2012. Architectural pen on cold-pressed paper, image size 46cm x 66cm (56cm x 76cm overall, unframed).

I spent my early childhood in the southwest of the United States. My mother was part-Cherokee, born and raised in Oklahoma, and my father was an Australian, but we lived for a long time in Los Angeles. We would often drive between the west coast and my mother's family in Tulsa, but we'd take these circuitous routes on unmapped back-roads, adding days and hundreds of miles to a journey that was already fifteen hundred miles long via the direct route on Interstate 40, through desert towns like Barstow and Winslow and Albuquerque.

They insinuated themselves into what I drew: skulls on snake bodies, '60s neon signs, tattooed women and grinning death-heads.

I still remember the weird roadhouses we stopped at, filled with faux-Native American trinkets, and Mexican candied skulls, as well as petrified tree fragments, fossils and pebbles of polished turquoise. We'd end each day in some rickety, half-dead town in Arizona, New Mexico or Texas, staying in a cheap motel with a swimming pool and a noisy ice-machine. Sometimes, we'd be so close to the Mexican border that it made no difference which side of it you were on – it could just as well have been Mexico but with better air-conditioning – and at this time of the year, the whole place would be overtaken with unsettling (but to a young kid, exciting) syncretic symbols and rituals, part Catholic, part ancient Toltec, part Hopi or Navajo, with black-robed Madonnas, painted skulls and masks, crucifixes and snake skeletons. It was never scary and solemn, only celebratory, not just honouring the dead but inviting them to a party, to spend time among friends and family. The barbecue smoke always smelled of mesquite.

Later, when I became an artist working on large, intricate drawings in ink on paper, the impressions of those road trips insinuated themselves into what I drew: skulls on snake bodies, '60s neon signs, tattooed women and grinning death-heads, the Robert Williams-influenced cars (my parents drove a cherry-red Chevy Impala SuperSport). Even the modern military references were derived from fleeting glimpses of fighters and tanks arrayed on open tracts of desert, at Nellis or Luke air force bases, or Camp Navajo. They seemed as commonplace as the motels, drive-in diners and cheesey girlie bars that littered our route.

— Berlin, 2013

Finn Lafcadio O'Hanlon was born in Brighton, England and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Los Angeles and Tokyo before returning as a teenager to Sydney's northern beaches. Now 22, he first exhibited his intricate drawings at the MiCK Gallery in 2011, and at the same time his photography at Wedge Gallery/Kinokuniya, both in Sydney.

Add new comment